Read Less

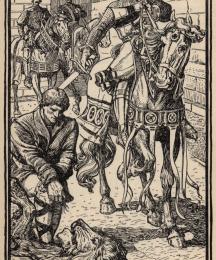

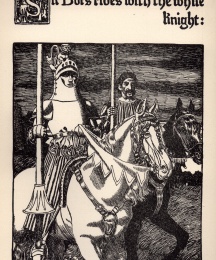

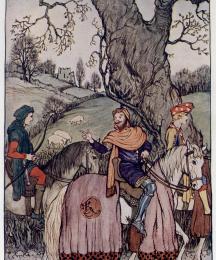

Horses are humanized in the bestiary tradition: "they grieve when conquered, they rejoice when they win" (156), traits that come to the Bestiary tradition via Isidore's writings (158n84). They are praised for their loyalty to their masters, and some, like Alexander the Great's horse Bucephalus, are said to accept no rider other than their masters (157). This close association between horses and humans recurs throughout medieval Arthuriana.

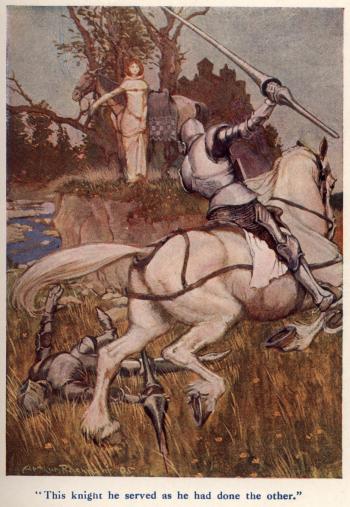

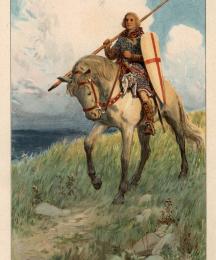

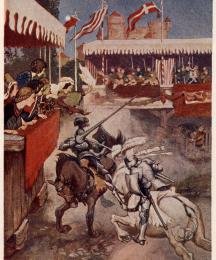

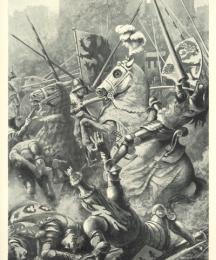

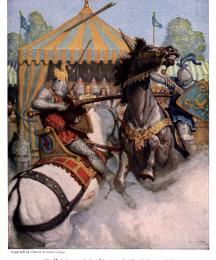

Knights and horses are, unsurprisingly, associated quite strongly. In Malory, Lamorak expresses this most succinctly when he encounters his brothers having been unhorsed: "'Bretherne, ye ought to be ashamed to falle so of your horsis! What is a knyght but whan he is on horsebacke?'" (2.667). A knight is not a knight, Lamorak suggests, when he is not riding his horse. In the Vulgate Cycle's

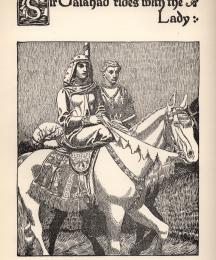

Lancelot, the

Lady of the Lake explains to

Lancelot why knights ride horses as follows: "know, too, that in the beginning, according to the Scriptures, no one but knights dared to mount a horse – a

cheval, as they said – and that is why they were called horsemen, or

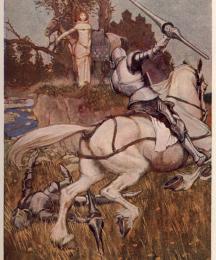

chevaliers" (2.59). The horse is said to signify the common people, who like the horse must bear the knight up (2.60). The quote emphasizes the centrality of horses to many tales of the Arthurian tradition, particularly their importance to knightly behavior. In the many encounters and battles between knights in medieval Arthuriana, knights on horseback often will not fight knights on foot because it is considered discourteous; horses, then, are a mark of equality between knights, and unhorsing a knight is a sign of defeat. One particular example of such appears in the "Morte Darthur" section of Malory, when

Arthur's forces and Lancelot's forces are fighting each other.

Bors unhorses Arthur and asks Lancelot if he should kill the king, but Lancelot rehorses Arthur instead (3.1192). Lancelot's act is seen as tremendously courteous and demonstrates his continued loyalty to Arthur even as they do battle and Lancelot is considered a traitor. This association between the knight and his horse may also explain the shame of riding in a cart in Chrétien's

Knight of the Cart since, as

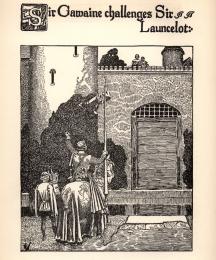

Gawain observes in the romance, "it would be base in the extreme to trade a horse for a cart" (175). By removing the knight from his horse, one removes his dignity, as well.

The tradition also suggests that an association between the nature of a horse and the character of its rider; the loathly lady in Chrétien de Troyes's

Perceval, for example, rides a mule. In contrast, the loathly lady in

The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle rides a particularly attractive palfrey, richly adorned, which emphasizes her ugliness but may also imply her true goodness/merit. In Chrétien's

Story of the Grail (Or

Perceval), Gawain's horse is stolen by another knight. Gawain is left with a nag instead, and he is most upset at this humiliation. The knight, in contrast, is overjoyed that he will lead away Gawain's horse Gringalet, and the evil maiden accompanying Gawain wishes that "if only the nag you took from the squire were a mare! That would please me, know this, for your humiliation would be worse!" (425). The maiden suggests that riding a female horse would be a slight to Gawain's masculinity. Riding an unworthy animal suggests character flaws and, perhaps, gender trouble. In Chrétien's

Perceval, the lady who is inadvertently wronged by the naïve young

Perceval has her horse punished as well; the horse's punishment is in much the same terms as the lady's. Just as she is not to be given new clothing or care, so too the horse is to go without new shoes or proper care; her knight tells her that "Your horse, when it throws a shoe, will never be reshod…. The clothes you are wearing will never be changed" (350). This is perhaps the most explicit connection between horse and rider in medieval Arthuriana, but such references are not limited to Arthurian texts; Chaucer's Clerk in the Canterbury Tales, for example, rides a famously lean horse: "As leene was his hors as is a rake, / And he nas nat right fat, I undertake" (GP 287-88). This Chaucerian example is generally interpreted as emphasizing the Clerk's poverty, yet it also suggests that the idea of horse as reflective of rider in some way is active in non-Arthurian texts as well. Yet the treatment of horses and their association with riders is particularly apt in narratives that concern themselves with courtly, chivalric behavior.

The ignorant title character in

Perceval of Galles rides a pregnant mare to court because he does not realize that there is a distinction between male and female horses (16-17). We learn, just later, that the mare is in fact pregnant and overweight (in comparison to the steed of the Red Knight, who Perceval is trying to catch up to) (26). He repeatedly calls other knight's horses mares until he is corrected. Perceval later alludes to this when he becomes suspicious of the Sultan during his fight; he thinks to himself "whethir [can] this be a stede / I wende had bene a mere?" (ll. 1691-92). This reference back to the earlier episode helps weave

Perceval of Galles together more tightly as well as emphasizing the development/change in Perceval's character. This passage from the romance, centered around the steed/mare confusion, shows Perceval's "arrival" as a mature knight, an essential moment in his development.

The young Lancelot in the Prose

Lancelot trades his horse for the feeble horse of a man trying to get to King Claudas's court to defend himself against a traitorous man (2.20-21). Here, the exchange for a weaker horse is a mark of Lancelot's goodness and courtesy, since he exchanges the horses to help a wrongly accused man.

Gawain's courtesy to horses serves him well in

Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle; he brings the Carle's horse in out of the rain when Kay has chased it from the barn. (This is the first test of Gawain's courtesy in the tale.) Similarly, in

The Carle of Carlisle (which is another version of the same tale), Gawain leads the horse and its foal in when

Kay casts them out of the barn. Kay and Gawain's respective treatment of the Carle's horses reflect each one's knightly ethos/courtliness, and their actions are essential to the Carle's later treatment of them. To some extent, the example is a cyclical one – Kay is discourteous because he treats the horses badly, which he does because he is discourteous and a bad guest – but the example validates the centrality of the horse in medieval Arthurian texts and reinforces both knights' places in Arthur's court.

This link between horses and knightly status may also be at work in Chrétien's

Erec and Enide, in which the two title characters travel across the country and, when passing knights challenge

Erec, he wins their horses and makes Enide lead the horses. Other knights then attempt to win the horses and take them away, providing Erec further chances to prove his valor by winning horses (37). Similarly, in the

Romance of Yder, Kei loses three very fine horses to Yder during a tournament, which results in much shame and mocking being directed at Kei. Yder wins five horses throughout the day; he then demonstrates his courtesy by sending the horses to his squire Luguain's father, who has been courteous and kind to him (65-71).

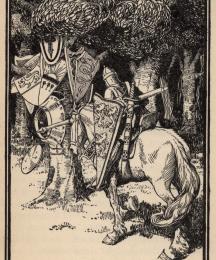

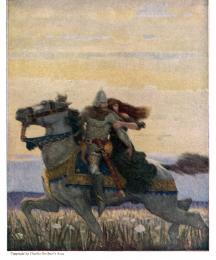

Knights are often identified by the horses they ride in Malory; for example, in Book Nine,

Palomydes is identified by his great black horse. Because of their proximity to – indeed, interaction with – knights, many horses are named.

Tristran's horse is named Passe-Brewel, and the narrator declares that it has been Tristram's horse for many years. Arthur's horse in Beroul's

Tristran is named Passelande (167), and Tristran's is named Bel Joeor (189). In

Erec and Enide, Arthur's horse is called Aubagu (52).

Perhaps the most famous named horse in the Arthurian tradition, Gawain's horse Gringolet (var. Gringalet), is described in the Lancelot-Grail Cycle's

Merlin as named for its great strength, "for the story says that it could run for ten leagues without heaving or panting, nor would there be any sweat on one hair of its rump or shoulder" (1.355). (The story gives no meaning for his name, though it is possible that it comes from the French

gringolé, translated as snake-headed. This seems a strange connection given Gringolet's valorization and the often negative associations with snakes in medieval Arthuriana, however.) Gringolet's idealized perfection seems to mirror the many descriptions of strong knights throughout the tradition, emphasizing the extent to which Gringolet too is a character. Gawain's horse is called Gringuljete in Wolfram von Eschenbach's

Parzival, and their adventures together are documented with unusual detail. When they must jump the Perilous Ford (

Li gweiz prelljus) so that Gawan can obtain a particular twig for his beloved Orgeluse, Gawan and Gringuljete fail to reach the other bank of the river; after saving himself, Gawan immediately seeks to save his horse. Gawan is fortunately able to use his lance to catch Gringuljete's bridle and bring him to shore without injury. (303) In the Dutch

Roman du Walewein, Gringolet is an integral part of one of Walewein's adventures. While Walewein (that is, Gawain) rides in search of a chess set he has promised to bring to Arthur, he and his faithful horse Gringolet encounter a nest of four baby dragons. Walewein begins to fight them, and Gringolet joins in the fight when he is attacked by one of the baby dragons. Having defeated all four, Walewein and Gringolet encounter the older dragon, which Walewein defeats using his spear – though Gringolet is unable to endure the great heat of the dragon's cave and waits outside for Walewein while the knight finishes off the dragon (41-55). The episode both demonstrates Walewein's great skill and bravery and elevates Gringolet to an almost knightly status as he comes to Gawain's aid against the dragons.

Horses are often used in metaphors, as well; in Thomas of Britain's

Tristran, Brengain compares Yseut to a colt. Just as Yseut is (to Brengain's view) a faithless perjurer who has been one since childhood, so a colt keeps the habits it learns when it is being broken in (79). This conveys some sort of practical, generalized "wisdom," reinforcing the centrality of horses to medieval Arthurian culture.

Interactions between animals and humans make up a large portion of the action of medieval Arthurian texts, but perhaps no animal is as central to these works as the horse. Connections between horse and rider are frequently understudied yet important relationships in these texts and deserve a great deal more critical attention.

BibliographyFor more information about the version of works cited, see the Critical Bibliography for this project.

Read Less

30e6.jpg?itok=BVRyYagJ)

f17f.jpg?itok=Y-xqfzmZ)

bc94.jpg?itok=4cUgPbB1)

97fd.jpg?itok=PSQ61a4f)

e2ca.jpg?itok=qbx837NY)

e63d.jpg?itok=i3h8_-cW)

0e93.jpg?itok=kcY0dMSV)

7ed6.jpg?itok=KS5fiVL9)