In the bestiary tradition, bears are described as having a weak head and strong arms. They give birth to unformed cubs, and the mother forms the cub's body by licking it once it is born (138). These strange attributes are not allegorized, and this lore seems largely absent from the depictions of bears in medieval Arthuriana, where...

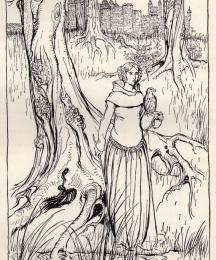

The bestiary tradition distinguishes among many varieties of birds, but it attributes some similarities to all of them. They protect their young with their wings and do not fly in direct routes (165-66). One particular type of bird discussed in the bestiary and common in medieval Arthuriana is the hawk, which the bestiary describes as...

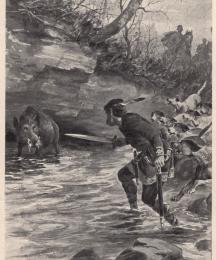

Boars are described in the bestiary tradition as fierce creatures (152), though no moral is prescribed to them. While boars serve several functions in medieval Arthuriana, the ferocity ascribed to them in the bestiaries is a consistent element of their appearances in Arthurian works.

Boars appear most frequently in hunts, and, often, they...

The bestiary tradition describes bulls as fierce, with hard hides, but provides no specific religious or symbolic significance to them (152-54). However, these descriptors may explain why they are used as a symbol for knights in their appearances in medieval Arthuriana. Bulls appear several times in Arthuriana, but these appearances...

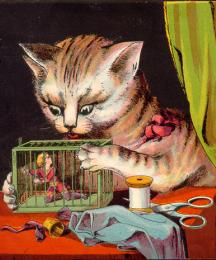

The bestiary tradition attributes two major features to cats; first, they attack mice, and second, they have excellent vision (161). These two traits do shape the depictions of cats in medieval art and literature. For example, Joyce Salisbury describes an image in the book of Kells which shows two cats having caught mice nibbling on a...

Berbiolette

In Chretien’s Erec, Erec wears a cloak with fur lining from “strange beasts, which have heads completely blond and necks as black as mulberries, with scarlet backs below, black stomachs, and dark-blue tails. Born in India, such beasts are called berbiolettes… [they] find their only nourishment in fish, cinnamon...

According to the bestiary tradition, deer are the enemies of serpents (Clark 134). Deer also migrate, which the tradition glosses to explain that deer are like good Christians, who change their homes from the world to heaven (Clark 135). These moral attributes are generally absent from medieval Arthurian texts, though deer appear quite...

The second family bestiary tradition comments on the intelligence of dogs, especially their ability to recognize their names, and describes them as very loyal (145). In fact, "often even dogs produced evidential proofs to contradict circumstances of a murder that was committed" (146); they mourn, and they can heal wounds by licking...

Dragons and serpents are very closely related in the bestiary tradition. Dragons are described as the largest of serpents; allegorically, they are like the Devil, who is sometimes presented as a monstrous serpent (194). Vipers, the type of snake given the most attention, are similarly described as wicked and cunning and are associated...

The bestiary tradition attributes a strange weakness to the elephant; it sleeps standing up, leaning against a tree, because once an elephant falls it is unable to stand back up (128). Elephants are uncommon in medieval Arthuriana, but the myth of an elephant's inability to rise may underlie its appearance in the Alliterative Morte...

Foxes are crafty, according to the bestiary tradition; they are able to play dead and lure birds close to capture them (Clark 141). These creatures are thus associated with the Devil, who tricks and ensnares Christians (142). Cunning is the defining attribute of foxes in their few appearances in medieval Arthuriana.

This...

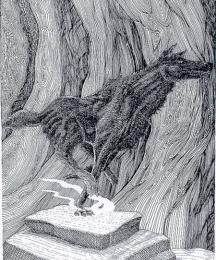

Griffins are described in the bestiary tradition as fierce, hostile to horses, and originating in mountainous places, though they are given no moral or spiritual meaning (Clark 127). These elements of the griffin are absent from their depictions in medieval Arthuriana. Gryffins are used as a heraldic device in the Awntyrs of Arthur,...

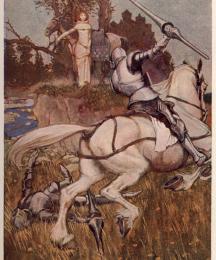

Horses are humanized in the bestiary tradition: "they grieve when conquered, they rejoice when they win" (156), traits that come to the Bestiary tradition via Isidore's writings (158n84). They are praised for their loyalty to their masters, and some, like Alexander the Great's horse Bucephalus, are said to accept no rider...

Hybrid creatures are particularly fascinating in light of new scholarly attention on monsters and monstrosity. While many of these creatures fall into other categories, (such as griffins) or appear throughout medieval Arthuriana (such as the Questing Beast), other hybrids appear only once. Several notable ones are considered here....

The bestiary tradition explicitly compares lions to Christ. In Physiologus, for example, two attributes of lions are described that link lions to Christ; first, the lion covers its tracks with its tail to evade hunters just as Christ hid His divine nature from those who did not believe in him. Second, lion cubs are born dead and are...

The Questing Beast (also called the Bizarre Beast or the Beste Glatisant) appears briefly in French and English medieval texts. In French, it appears in three thirteenth-century texts – the Prose Tristan, Perlesvaus, and the Post-Vulgate cycle.1 In English, it appears in Malory’s fifteenth-century Morte D'Arthur. The creature's...

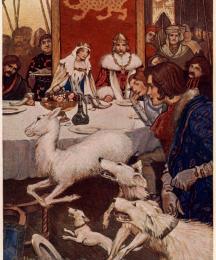

The Unicorn is described as fierce in the Bestiary tradition, but it is also said to be symbolic of Christ (Clark 126). Because only a virgin can be used to capture a unicorn, "thus our Lord Jesus Christ is spiritually the unicorn" because he was born of a virgin mother (126).

Unicorns appear less commonly than one might...

Wolves are described in the bestiary tradition as greedy and bloodthirsty (Clark 142), and they are, in this way, like the devil (Clark 143). This association with evil may have some influence on wolves' function in medieval Arthuriana, where their infrequent appearances associate them with violence or deception.

In the Middle...