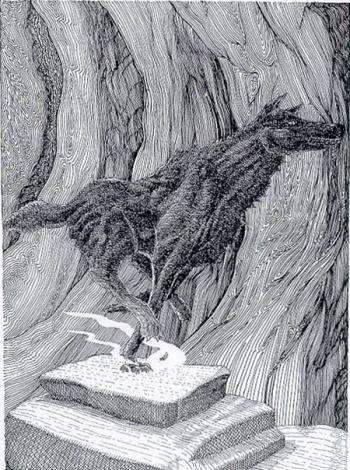

The second family bestiary tradition comments on the intelligence of dogs, especially their ability to recognize their names, and describes them as very loyal (145). In fact, "often even dogs produced evidential proofs to contradict circumstances of a murder that was committed" (146); they mourn, and they can heal wounds by licking them (147). The bestiary thus compares dogs to preachers, who heal men's wounds by hearing confession (147-48).

These traits of loyalty and intelligence commonly appear in the dogs of medieval Arthuriana. In Malory, for example,

Lancelot follows a brachet into a castle, where he finds it licking its dead master. This example closely parallels a description of dogs in the second family bestiary; the dog stands near the corpse of its master and "with mournful plaint, bewailed the fate of his master. As it happened, he who committed the murder ventured into the circle of spectators… Thereupon, the dog, its cries of grief set briefly aside, took up the arms of revenge, and seized and held the man" (147). In Malory's

Morte d'Arthur, Lancelot sees "lye dede a knyght that was a semely man, and that brachette lycked his woundis" (1.278). While this could imply familiarity with the bestiary tradition, Willene Clark notes that the story is Aesopic in origin (147n140). It is similar, however, to an episode Malory's "Boke of Syr Trystrams de Lyones," in which

Tristan's loyal brachet recognizes the sick (and disguised) Sir Tristran (2.501-02). Both Lancelot and Tristan's encounters, then, likely draw on familiar cultural understandings of dogs' natural loyalty.

Dogs feature at several...

Read More

Read Less

The second family bestiary tradition comments on the intelligence of dogs, especially their ability to recognize their names, and describes them as very loyal (145). In fact, "often even dogs produced evidential proofs to contradict circumstances of a murder that was committed" (146); they mourn, and they can heal wounds by licking them (147). The bestiary thus compares dogs to preachers, who heal men's wounds by hearing confession (147-48).

These traits of loyalty and intelligence commonly appear in the dogs of medieval Arthuriana. In Malory, for example,

Lancelot follows a brachet into a castle, where he finds it licking its dead master. This example closely parallels a description of dogs in the second family bestiary; the dog stands near the corpse of its master and "with mournful plaint, bewailed the fate of his master. As it happened, he who committed the murder ventured into the circle of spectators… Thereupon, the dog, its cries of grief set briefly aside, took up the arms of revenge, and seized and held the man" (147). In Malory's

Morte d'Arthur, Lancelot sees "lye dede a knyght that was a semely man, and that brachette lycked his woundis" (1.278). While this could imply familiarity with the bestiary tradition, Willene Clark notes that the story is Aesopic in origin (147n140). It is similar, however, to an episode Malory's "Boke of Syr Trystrams de Lyones," in which

Tristan's loyal brachet recognizes the sick (and disguised) Sir Tristran (2.501-02). Both Lancelot and Tristan's encounters, then, likely draw on familiar cultural understandings of dogs' natural loyalty.

Dogs feature at several points in the Tristran story, and their appearances are surprisingly consistent across versions. In the Middle English

Sir Tristrem, the little dog Hodain laps from the cup that contained the love drink Tristrem and Ysonde have consumed. As a result, Tristrem and Ysonde "loved with al her might / And Hodain dede also" (1694-95). Later in this version, Tristrem defeats the giant Urgan, who seeks to abduct Blancheflour, King Triamour's daughter. As a reward for saving Blancheflour, Tristrem is given a puppy named Peticrewe, which he then sends to Ysonde (224). The dog later accompanies them into exile when Mark sends them from the kingdom (226). In von Strassburg's

Tristan, the little dog Petitcreiu similarly functions as a love-token between Tristan and Isolde. Here, Tristan obtains the dog from Duke Gilan. Petitcreiu is a magical, multicolored animal that wears a chain of gold around its neck. A bell hangs from the chain, and that bell's ringing cures Tristan of his love-longing for Isolde as long as Petitcreiu is in Tristan's presence (208-09). Tristan won the dog from a reluctant Gilan by killing a giant who torments Gilan's people. Tristan sends the dog to Isolde, and to prevent anyone from suspecting the relationship between her and Tristan, she claims that the dog was sent to her by her mother. Isolde keeps Petitcreiu in her sight at all times, but she breaks the magical bell off the dog's collar so that she can share in the troubles and sorrows Tristan experiences (215).

Tristran's hunting dog is named Husdent in Beroul's version of Tristran's story. Tristran trains Husdent not to bark, so that Tristran and Isolt will not be found in the forest (69). In addition, Iseut takes Husdent back to court with her as a reminder of Tristran when she is reconciled with

Mark. Husdent is notable in Beroul's version for his intelligence and his loyalty, two of the major traits attributed to dogs in the bestiary tradition. In Gottfried von Strassburg's

Tristan, the dog is named Hiudan rather than Husdent, but as in Beroul, Tristan teaches the dog not to bark and uses it to help hunt for food for himself and Isolt.

Like

deer,

boar, some

birds, and many other animals, hounds are commonly part of hunting trips. In

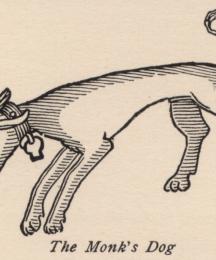

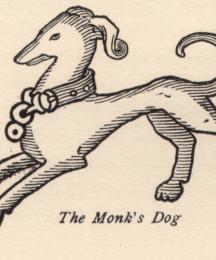

Lancelot of the Laik, the King sets out on a hunt with hounds (26). Hounds appear in each of the three hunts in

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; the poem includes detailed descriptions of hunting, and greyhounds are mentioned by name as one of the dogs used in the hunt (1171). The use of dogs in hunting is associated with courtly life. In Chrétien's

Cliges, Cliges' nobility is expressed through his knowledge of hawks and hunting dogs (121); he is explicitly compared to Tristan on these matters.

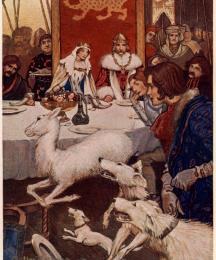

In Malory's Tale of King Arthur, a white bratchet, pursuing a white hart, runs through the hall during

Arthur's marriage feast. These beasts then become the impetus for an early adventure in the text when

Gawain, Pellinore, and Tor go out in search of them. In the earlier Post-Vulgate Cycle account of Arthur's wedding feast, this white bratchet is a black dog, which the new knight Tor pursues (4.235).

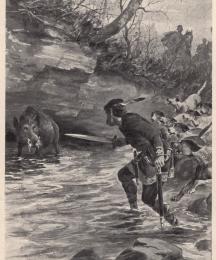

Arthur's dog in Nennius's

Historia Brittonum is named Cabal (var. Cafall, Cavall), and it features in a wonder of the British Isles. Nennius writes that "There is a mound of stones there and one stone placed above the pile with the pawprint of a dog in it. When Cabal, who was the dog of Arthur the soldier, was hunting the boar Troynt, he impressed his print in the stone, and afterwards Arthur assembled a stone mound under the stone with the print of his dog, and it is called the Carn Cabal. And men come and remove the stone in their hands for the length of a day and a night; and on the next day it is found on top of its mound." The dog's impact on the landscape here serves as proof of his existence that continues to this day. Cabal also appears in

Cuhlwch and Olwen, a tale of the

Mabinogion; in the Welsh version, Arthur's dog kills the boar, here called the Twrch Trwyth, and thus completes one of the tasks necessary for Cuhlwch to win Olwen: "Now the boar was not slain by the dogs that Yspaddaden had mentioned, but by Cavall, Arthur's own dog." Just as horses and other creatures strongly associated with particular knights, here Arthur's dog receives similar honor and recognition. The similar account, present in both early Welsh and Latin materials, suggests mutual familiarity and may suggest that Arthurian tales were being shared orally in the British Isles.

Greyhounds in Arthurian texts are often associated with

Lancelot. The young Lancelot in the Prose

Lancelot trades his horse for the feeble horse of a man trying to get to King Claudas's court to defend himself against a traitorous man. Riding the feeble horse, Lancelot then trades a freshly hunted roebuck he has caught for a greyhound. (The roebuck is given to an aged gentleman, who has been hunting to provide for his daughter's wedding feast.) Lancelot is beaten by his tutor for saying that the greyhound is worth two of his own horses; it is only when the tutor strikes the greyhound that Lancelot retaliates by beating him in return (2.20-21). Greyhounds appear later when the

Lady of the Lake brings the young

Bors and Lionel to live in her kingdom with Lancelot. After she whisks the children away, King Claudas, who has been keeping the children prisoner, captures two greyhounds that look like the children in form (2.29). This association between Lancelot and greyhounds is fascinating given that greyhounds are also associated with healing and divinity (Schmitt,

The Holy Greyhound). In the Middle English

Sir Gowther, for example, the title character is fed by greyhounds while he undergoes penance. Though this is not an Arthurian romance, the special status of greyhounds here suggests that their status in Arthurian romance is representative of how they are viewed throughout the high and later middle ages.

BibliographyFor information about editions cited, see the Critical Bibliography for the Arthurian Bestiary.

Read Less