The bestiary tradition distinguishes among many varieties of birds, but it attributes some similarities to all of them. They protect their young with their wings and do not fly in direct routes (165-66). One particular type of bird discussed in the bestiary and common in medieval Arthuriana is the hawk, which the bestiary describes as courageous. They are also effective parents who force their young to hunt for prey early; the hawk "takes care that they [baby hawks] not become lazy in their youth" (181).

This courageousness may explain why hawks are so commonly used in hunting in medieval Arthurian works. Several characters, most notably

Tristan, are associated with hunting and thus with hawking; examples of this association include both the French Prose

Tristan and Malory's

Morte d'Arthur. In Chretién's

Cliges, the title character's nobility is clear through his knowledge of hawks and hunting dogs (121); he is explicitly compared to Tristan on these matters. The association with hawking in particular serves as a marker of a knight's courtliness.

Birds of various kinds are also offered as prizes. In

Sir Tristrem, Tristrem and Rohand, his foster father, play chess for hawks; Tristrem wins six hawks in their games (164-5). The challenges one must face to win a bird are sometimes more serious than a game of chess, however. In Malory's

Morte d'Arthur,

Lancelot, hiding his identity with the name Le Chavaler Mal Fet, offers a fair maid and a gerfalcon to any knight who can defeat him in battle (2.827). Winning a bird also drives the plot in an early episode of...

Read More

Read Less

The bestiary tradition distinguishes among many varieties of birds, but it attributes some similarities to all of them. They protect their young with their wings and do not fly in direct routes (165-66). One particular type of bird discussed in the bestiary and common in medieval Arthuriana is the hawk, which the bestiary describes as courageous. They are also effective parents who force their young to hunt for prey early; the hawk "takes care that they [baby hawks] not become lazy in their youth" (181).

This courageousness may explain why hawks are so commonly used in hunting in medieval Arthurian works. Several characters, most notably

Tristan, are associated with hunting and thus with hawking; examples of this association include both the French Prose

Tristan and Malory's

Morte d'Arthur. In Chretién's

Cliges, the title character's nobility is clear through his knowledge of hawks and hunting dogs (121); he is explicitly compared to Tristan on these matters. The association with hawking in particular serves as a marker of a knight's courtliness.

Birds of various kinds are also offered as prizes. In

Sir Tristrem, Tristrem and Rohand, his foster father, play chess for hawks; Tristrem wins six hawks in their games (164-5). The challenges one must face to win a bird are sometimes more serious than a game of chess, however. In Malory's

Morte d'Arthur,

Lancelot, hiding his identity with the name Le Chavaler Mal Fet, offers a fair maid and a gerfalcon to any knight who can defeat him in battle (2.827). Winning a bird also drives the plot in an early episode of Chretién's

Erec and Enide.

Erec encourages Enide to challenge another lady for the sparrowhawk which is given to the most beautiful and courteous woman there (11). It is through Erec's defense of Enide's claim that Erec wins Enide to be his wife. The use of birds such as hawks as prizes seems linked to their value as hunting birds and their associations with the court.

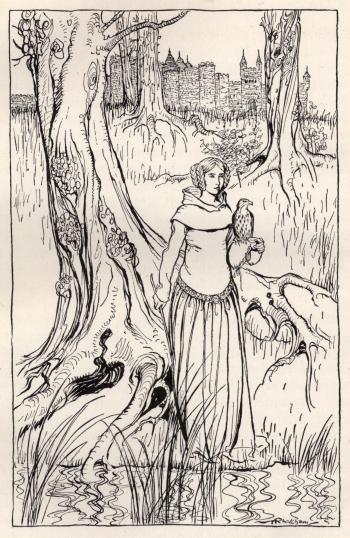

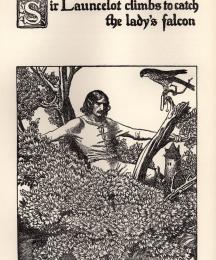

As domesticated animals, birds can be manipulated by their owners in some works. In Malory's

Morte d'Arthur, Lancelot is tricked into fighting a knight through the use of a hawk. He encounters a young lady feigning distress because her bird has escaped into a tree and tells Lancelot that her husband, Sir Phelot, will be furious with her. When Lancelot disarms himself and climbs the tree to fetch the bird, the lady's husband appears, armed and eager to slay Lancelot when he descends from the tree. Lancelot demands to know why the lady has betrayed him, but Sir Phelot replies that it was at his order. In the fight, Lancelot slays Sir Phelot (1.283-84). The bird here functions as a plot device, and the episode provides further proof of Lancelot's worthiness as a knight – both because he assists the lady and because he defeats Sir Phelot without his armor.

Birds are used as components of plot in some works, while in others they are commonly used to describe setting. Birds are used in

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight to convey both the arrival of spring and cold of winter: as spring approaches, "Bryddez busken to bylde and bremlych syngen" (509), but as

Gawain rides in search of the Green Chapel and Christmas nears, "mony bryddez vnblyϸe vpon bare twyges, / ϸat pitosly ϸer piped for pyne of ϸe colde" (746-47). The

Alliterative Morte Arthure features a passage, just before

Arthur fights the giant of Mont St. Michel, rich in bird imagery, where falcons, pheasants, cuckoos, and other birds sing happily together by a river (160). This appearance in the Alliterative

Morte makes the giant's monstrosity all the sharper as it contrasts with the almost pastoral description of birds, and it is unusual because the bird imagery more often reflects the mood of the text, as in SGGK. Many sections of

Lancelot of the Laik also feature bird imagery, in which birds sing pleasantly and mark the arrival of morning (22). Moreover, the work begins with a bird providing love advice; in the poem's opening dream vision, a bird appears to the narrator and orders him to write a poem to serve the narrator's beloved (14). This use of birds advising an author in dreams appears in other medieval works (for example, Chaucer's

House of Fame); this detail thus suggests how Arthurian texts draw on many of the same animal tropes as other medieval works.

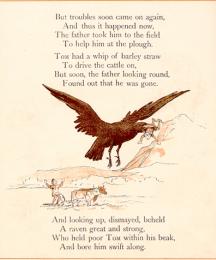

Yet not all the birds in medieval Arthuriana are domesticated or pleasant. The Vulgate Cycle's

History of the Holy Grail discusses a bird called Serpilion at some length; this bird flies to the stone on which King Mordrain finds himself stranded (presumably as a test of his faith) and strikes him, so that he falls over. The description of the bird is allegedly from Scripture; it never flies, save to frighten those whom Christ wishes to frighten, and other birds and beasts run from it. The female brings forth eggs without a male, and the eggs are completely cold; the mother finds a stone that becomes warm when rubbed and then carries that warmth (though not the stone itself) back to the eggs. Though this warms the eggs and causes them to hatch, the great heat causes the mother bird to be burned. The small birds then eat her ashes (1.66). The description is not unlike something one might find in a bestiary, though it does not appear in one; the creature seems to share some similarities with the phoenix.

In addition to these many appearances of birds, some types of birds are notable enough to require further discussion. These are featured below.

Owl

In the bestiary tradition, owls are marked by flying at night, presumably because they cannot see in the sunlight (178). This association with night may influence the use of owls to describe people bringing bad news in Thomas of Britain's

Tristan, in which Yseut describes Cariado, a knight who seeks her love, as a wood-owl. When Cariado brings Yseut news of Tristan's marriage to Yseut of the White Hands, he tells her that the song of the wood-owl signifies death. She in turn calls him a wood-owl for bringing her the news (49). (Presumably, the death in question is Yseut's own.)

Pelican

In Wolfram von Eschenbach's

Parzival, the knight-hermit who tells Parzival of the efforts to heal the Maimed King may have had knowledge of the bestiary tradition. He explains that the court used the blood of a pelican to attempt to heal the king, but their effort fails (245). Though pelican's blood is not effective medicine in

Parzival, the pelican has healing abilities in the bestiary tradition. The bird strikes its own young and kills them, but then it feels regret. On the third day, the mother pelican, "piercing her own breast, opens her side and leans over her chicks and pours her blood over the dead bodies and thus raises them from the dead" (178). The reference in the bestiary is clearly to Christ, who saves his Christian children through his blood.

Phoenix

The phoenix appears rarely in medieval Arthurian literature. Fenice, the heroine of Chretién de Troyes's

Cliges, is compared to the phoenix for her unique beauty, but the name is also appropriate given her apparent death and rebirth within the romance's plot. This single reference draws on the same lore as the bestiary tradition in so far as the phoenix is unique and lives in cycles of death and resurrection, but it does not, like the bestiary, explicitly allegorize the phoenix as a symbol of Christ (175-6).

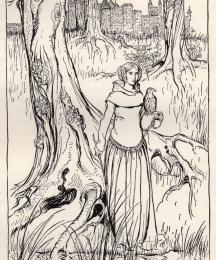

Parrot

The parrot appears in a French romance called

Le Chevalier du Papegau (

The Knight of the Parrot), a romance which features Arthur himself as a knight errant in distant kingdoms. Arthur leaves the kingdom in the care of King Lot and goes on a series of adventures that culminate with his encounter with the Giant Without A Name. Arthur is known throughout the romance as The Knight of the Parrot, an assumed identity which helps to separate him from his identity as the king at court and thus allows him the freedom to act as a knight errant and exist in a romance where "force of arms, not law, reigns supreme" (Vesce xv). The parrot accompanies Arthur on his journeys and advises him, as well as recounting Arthur's adventures when they return to court. As a result, the parrot becomes representative of the adventures themselves, a unifying presence across the episodes narrating Arthur's time away from his own court.

Babian

The Babian appears in

Daniel of the Blossoming Valley, and it is described as a prized exotic bird commonly owned by women. “Such a wondrous plumage has the Babian that I hear the women speak of seeing their own reflection in it – as clearly as in a mirror” (13). These birds are trained to provide relief from the sun’s heat, and they emit light, so that their owners can see at night “as though from a burning candle” (13).

BibliographyFor more information about the version of works cited, see the Critical Bibliography for this project.

Read Less