Read Less

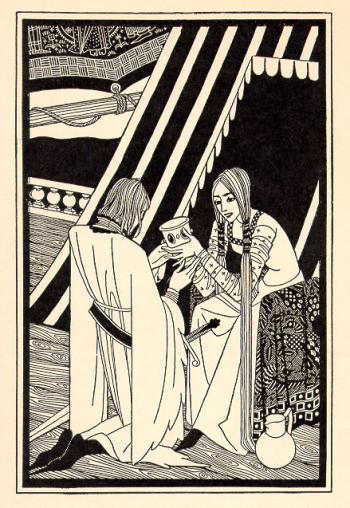

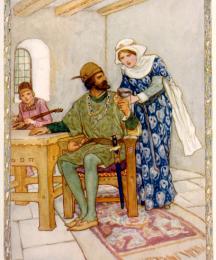

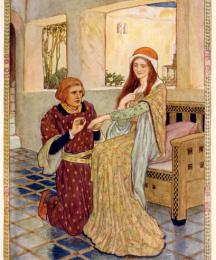

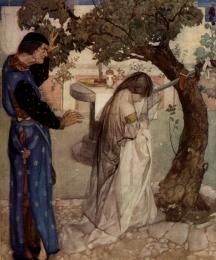

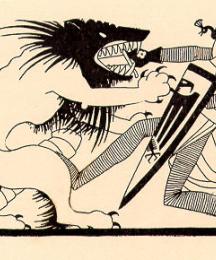

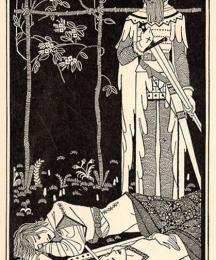

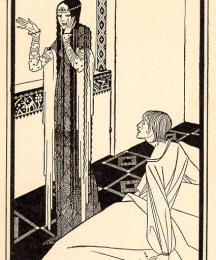

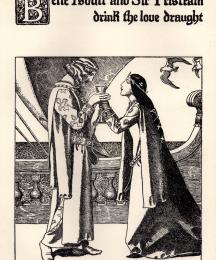

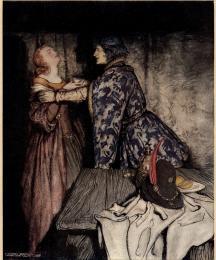

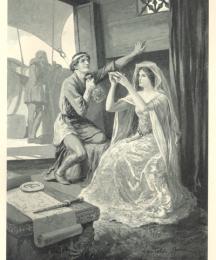

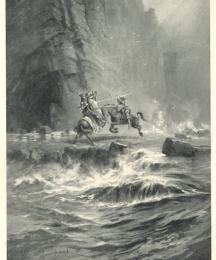

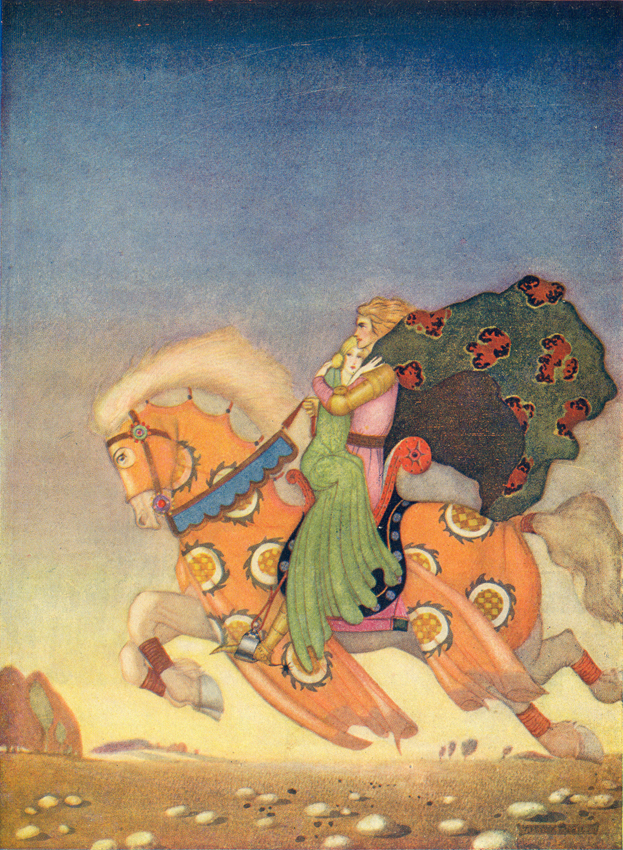

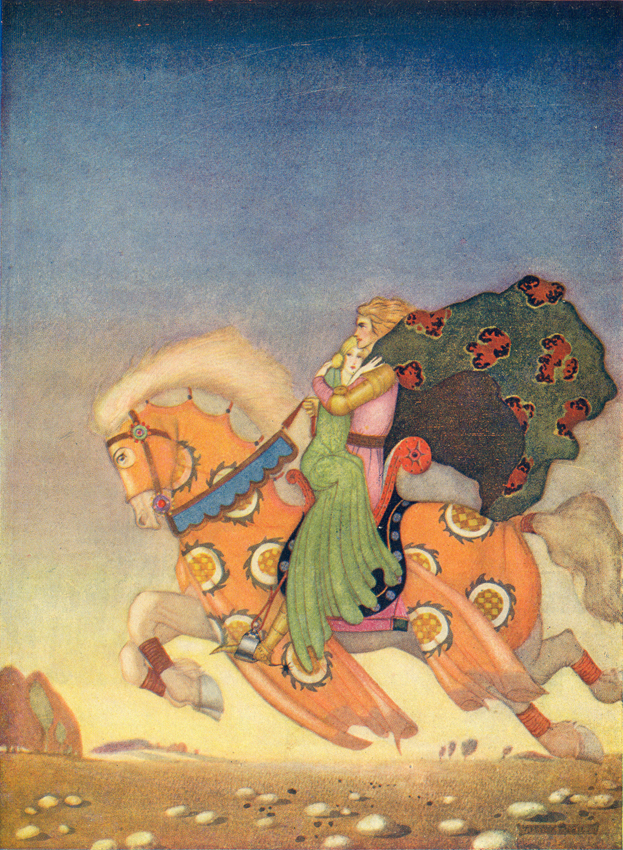

Tristan and Isolt's conflict of love and loyalty is one of the classic tales of Western literature; in the Arthurian tradition, their tragic tragectory rivals and complements that of Lancelot and Guinevere. The basic story is one of mis-directed love: Tristan, the heroic nephew of King Mark of Cornwall, is sent to Ireland to escort the Irish king's daughter, the beautiful Isolt, to Cornwall to become his uncle's bride. In most versions, it is during the return voyage that Tristan and Isolt accidentally consume a love potion (meant to ensure Isolt's happiness with Mark) together, and fall in love. Because Isolt's engagement to Mark cannot be broken, she marries the king despite her love for Tristan, and the two lovers spend the rest of their lives attempting to satisfy their desire for each other without revealing that desire to Mark and the Cornish court. The tale of potion-induced passion has proved irresistable to artists in all media, from literature to visual arts to music, to the point that Wagner's opera

Tristan und Isolde is now more famous than the text on which it is based, the thirteenth century

Tristan and Isolde of Gottfried von Strassburg. Virtually all versions of the legend revolve around conflicting themes of romantic love and political loyalty, though no two tellings treat these themes identically.

Tristan and Isolt in the Middle Ages

Scholarly speculation places the geographical origins of the Tristan and Isolt legend anywhere from Ireland to Cornwall to Wales to Persia. The biggest disputes in Tristan scholarship tend to be between the camp known as the "Celticists" who support the idea of a Celtic origin for the story, and those who support a Persian source. However, the arguments for a Persian source are as yet circumstantial, and no direct links have been proven.1 The Celticists have stronger evidence for their claims, as the earliest direct mentions of the characters are found in Celtic material. The Welsh Triads, thought to be a series of mnemonic devices created to help storytellers remember their tales, mention Drystan, son of Tallwch and nephew of March, who is lover to his uncle's wife Essylt. Connections have been made between these figures and a Pictish King known as Drust son of Tallorc, though given the popularity of "Drust" as a Pictish name, this cannot be viewed as concrete evidence of a historical Tristan. Much has been made as well of a pair of Irish tales, "Diarmaid and Grainne" and "The Wooing of Emer," that contain similar thematic material. As with the Persian material, however, no direct relationships have been proven, and they most likely are analogs rather than direct ancestors or descendants of the Tristan stories.

In terms of the full-blown legend as it appears in France and Germany after the eleventh century, scholars have generally assumed that there is some sort of archetypal Ur-Tristan that gave birth to the two strains of Tristan narrative. These two strains are generally known as the "version commune," the supposedly coarser "primitive" strain that includes Beroul and Eilhart von Oberge, and the "version courtoise," the refined "courtly" branch that includes Thomas d'Angleterre and Gottfried von Strassbourg. These are problematic designations; due to the lack of an archetypal version of the story, it is impossible to say whether the "primitive" versions are closer than the "courtly" versions to this imagined archetype. In addition, the use of "primitive" implies some artistic deficiency or lack of sophistication as compared to a more elegant and refined "courtly" version; upon comparison of examples from the two strains, it is clear that this is not the case. The true reasoning behind the division comes mostly from the fact that the version courtoise seems to be more focused on emotion and a concept of love that corresponds to the idea of courtly love as it developed in the French court during the 12th century; the stories focus in great detail on the emotional turmoil undergone by the lovers. The version commune, by contrast, generally has a more crisis-driven plot and contains some rather disagreeable episodes, such as the one in which an angry Mark turns Isolde over to a leper colony so that they may rape her in punishment for her infidelity to her husband. Another major contrast between the two versions lies in the treatment of the love potion's strength. In the version courtoise, the love potion's effect is permanent. By contrast, the effects of the love potion wear off after a few years in the versions commune. Norris Lacy, however, argues that this division is artificial: "despite initial appearances, the 'primitive' and so-called 'courtly' versions show no fundamental difference in their treatment of the love potion". 2 He continues on to explain that, although the versions communes state specifically that the potion wears off, the lovers continue to act as though the potion is still in effect; similarly, in the versions courtoises, there are hints that Tristan and Isolde at least find each other attractive long before they ever drink the potion. Hence both versions to a greater or lesser degree acknowledge the difficulty of laying the full blame for the affair on a love-potion, implying that the love potion is not the only force at work, and that the lovers are somewhat to blame for the events that shape their lives and the lives of those around them. One Middle English treatment of the legend, the poem Sir Tristrem, highlights these issues in a humorous fashion; when Tristrem and Ysonde mistakenly drink of the love potion, Tristrem's hound Hodain licks out the cup. The poet writes of the new-made lovers and hound, "Thai loved with al her might / And Hodain dede also."3

In terms of the full-blown legend as it appears in France and Germany after the eleventh century, scholars have generally assumed that there is some sort of archetypal Ur-Tristan that gave birth to the two strains of Tristan narrative. These two strains are generally known as the "version commune," the supposedly coarser "primitive" strain that includes Beroul and Eilhart von Oberge, and the "version courtoise," the refined "courtly" branch that includes Thomas d'Angleterre and Gottfried von Strassbourg. These are problematic designations; due to the lack of an archetypal version of the story, it is impossible to say whether the "primitive" versions are closer than the "courtly" versions to this imagined archetype. In addition, the use of "primitive" implies some artistic deficiency or lack of sophistication as compared to a more elegant and refined "courtly" version; upon comparison of examples from the two strains, it is clear that this is not the case. The true reasoning behind the division comes mostly from the fact that the version courtoise seems to be more focused on emotion and a concept of love that corresponds to the idea of courtly love as it developed in the French court during the 12th century; the stories focus in great detail on the emotional turmoil undergone by the lovers. The version commune, by contrast, generally has a more crisis-driven plot and contains some rather disagreeable episodes, such as the one in which an angry Mark turns Isolde over to a leper colony so that they may rape her in punishment for her infidelity to her husband. Another major contrast between the two versions lies in the treatment of the love potion's strength. In the version courtoise, the love potion's effect is permanent. By contrast, the effects of the love potion wear off after a few years in the versions commune. Norris Lacy, however, argues that this division is artificial: "despite initial appearances, the 'primitive' and so-called 'courtly' versions show no fundamental difference in their treatment of the love potion". 2 He continues on to explain that, although the versions communes state specifically that the potion wears off, the lovers continue to act as though the potion is still in effect; similarly, in the versions courtoises, there are hints that Tristan and Isolde at least find each other attractive long before they ever drink the potion. Hence both versions to a greater or lesser degree acknowledge the difficulty of laying the full blame for the affair on a love-potion, implying that the love potion is not the only force at work, and that the lovers are somewhat to blame for the events that shape their lives and the lives of those around them. One Middle English treatment of the legend, the poem Sir Tristrem, highlights these issues in a humorous fashion; when Tristrem and Ysonde mistakenly drink of the love potion, Tristrem's hound Hodain licks out the cup. The poet writes of the new-made lovers and hound, "Thai loved with al her might / And Hodain dede also."3

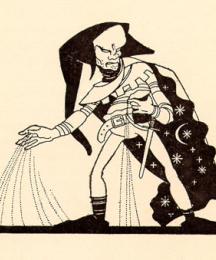

Although the differences in treatment of the love potion are slight, medieval authors' treatment of Mark varies widely. Some authors, like Malory (who draws on the Prose Tristan), go out of their way to make Mark into an irrational, sadistic man. Others, including both Thomas and Beroul, seem to have a sympathetic view of Mark as a conflicted, loving husband and uncle, "waver[ing] between his love for his wife and nephew and his appreciation of the barons' position [that Marc should punish the adulterers much more severely for their crimes]."4 In many ways, likewise, the portrayal of the lovers themselves differs from work to work, and often seems to be inversely related to Mark's goodness or lack thereof. Beroul, who creates a sympathetic Mark, makes the lovers almost malicious, seeming to delight in their ability to misdirect Mark whenever he becomes suspicious. By contrast, the Prose Tristan, the work on which Thomas Malory drew most heavily, creates a noble and sympathetic Tristan who is a perfect foil for his cruel and sadistic uncle. In regard to the Prose Tristan's Mark, Vinaver comments that "it is Tristan's duty, not his misfortune, to act as his rival and keep him in check . . . The tragic tale of unlawful love yields its place to a romance of chivalry with its characteristically simple scale of values, its exaltation of chivalric virtues, and its condemnation of all that lies beyond the narrow boundaries of the 'adventurous kingdom.'" 5 The Prose Tristan's Mark falls unarguably on the "evil" end of this "simple scale of values," acting as a foil against whom the models of chivalry, Tristan and Lancelot, can be clearly delineated in their full heroic glory. No one version seems to be authoritative in its depictions of the major figures; the portrayal of both Mark and the lovers seems to be dependent entirely on the goals of individual writers.

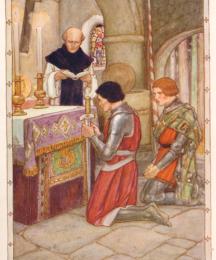

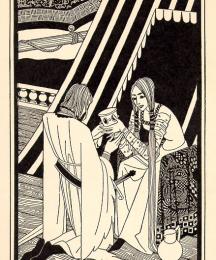

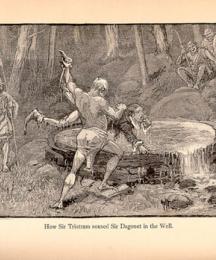

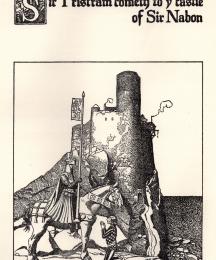

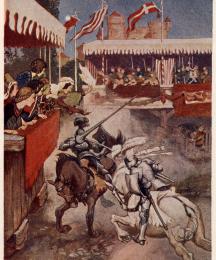

The most influential medieval telling of Tristan and Isolde's tragedy was that written by the mysterious "knyght presoner" Sir Thomas Malory as part of his collection of tales delineating the rise and fall of King Arthur, commonly known as the Morte d'Arthur. Malory's treatment of the Tristan material is notable for its concentration on Tristan's chivalric behavior and feats of valor. Even more than the Prose Tristan (from which Malory obtained the larger part of his Tristan material), The Book of Sir Tristram de Lyones shapes its episodes in ways that emphasize Tristram's developing nobility, and even somewhat de-emphasize the love aspects of the story. One excellent example of this occurs during Tristram's youth, which Malory condenses greatly. A large section of the Prose Tristan's material, covering the period between his father's death and Tristan's arrival in his uncle's court, is almost completely cut from Malory's narrative. A single uncontextualized paragraph explaining how the daughter of King Faramon of France sends Tristan love letters, and that Tristan's rejection causes her to die of a broken heart is all that remains of a rather lengthy episode that the Prose Tristan sets during Tristan's education in Faramon's court. Malory does say that Tristan goes to France to "lerne the langage and nurture and dedis of armys," (outlining Tristan's education, establishing his musical ability, and describing his hunting ability: "he laboured in huntynge and in hawkynge — never jantylman more than ever we herde rede of . . . And therefore the booke of [venery, of hawkynge and huntynge is called the booke of] sir Trystrams" 6), but completely removes the main substance of the Prose Tristan's account of Tristan's time in France. This vanished substance consists of an episode in which the French princess falls in love with Tristan, tries to gain his love by accosting him in a dark room, then accuses him of rape when he rebuffs her advances, all events that precede Malory's account of the final heartbroken letter and gift of a hunting dog that arrive with news of the princess' death. Similarly, later parts of the narrative dealing with love matters have their events related in such a way that descriptions of trysts and negotiations for trysts are greatly compressed in favor of moving more quickly on to any associated battles. 7 Malory's audience, it seems, had little patience for emotional monologues or lovelorn pillow-talk; they preferred instead that the storyteller move straight to the bloody, exciting bits.

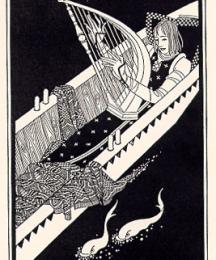

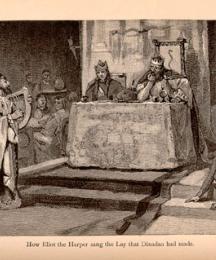

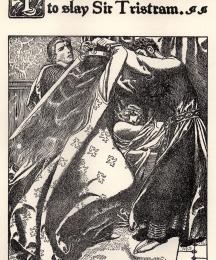

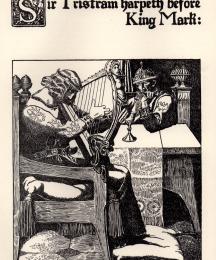

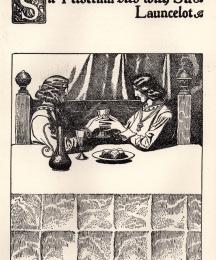

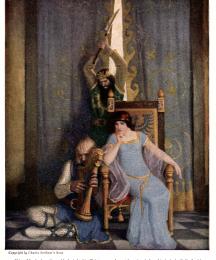

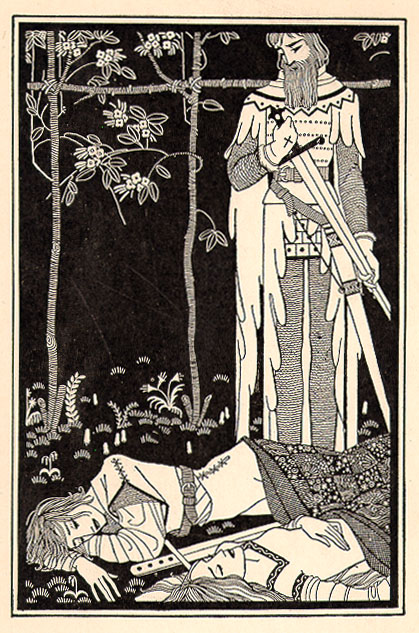

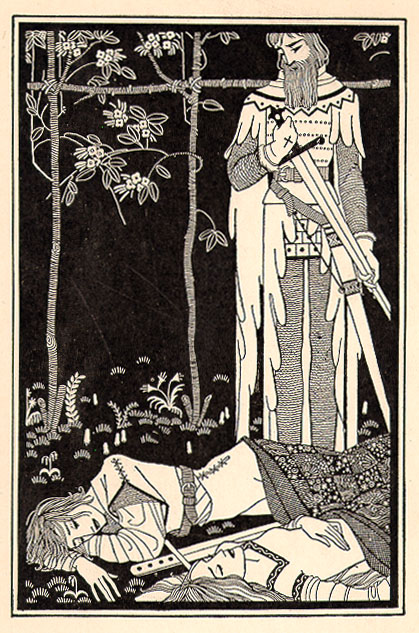

In spite of this preference for action over love, Tristan and Isolde hold a place in the Morte comparable to that of the other great love story, that of Lancelot and Guinevere. Lancelot and Tristan are called the two greatest knights and greatest lovers by Merlin, and the fairness of the two ladies is often compared. The basic outline of their tales is similar in that both knights are caught in a dangerous triangle of emotion that pits their love for their ladies against their loyalty to their king. The stories of the pairs are not, however, merely variations on a theme; there are notable contrasts between the two tales, not the least of which is the disparity between the two kings involved-- the generally noble and good Arthur has little in common with the malicious Mark. Also of note is the choices that Malory makes in regards to each tale's ending. While the Lancelot and Guinevere pairing remains a major focal point throughout the work (to the degree that consequences of their relationship give rise to the main dramatic action of the Morte's ending), the Tristan-Isolde pairing dominates only The Book of Sir Tristram, which ends before Tristram's death at Mark's hands. The death, in fact, takes place off-screen, a side-note that comes up as a result of a reference to Sir Bellyngere le Bewse and Alexander the Orphan, who are named in the catalogue of knights that directly precedes the healing of Sir Urry. The dramatic death inherent in other versions is elided; here, Mark's treacherous attack on the unarmed harping Tristram is remarked upon only in passing, and readers are completely insulated from the heartbreak felt by a dying Tristram who believes that his love has abandoned him. By deflecting and downplaying the dramatic moment of the Tristram and Isolde material, Malory preserves the continuing tension of the Lancelot-Guinevere relationship, which is central to the overall trajectory of his narrative in a way that Tristram and Isolde's story is not.

In spite of this preference for action over love, Tristan and Isolde hold a place in the Morte comparable to that of the other great love story, that of Lancelot and Guinevere. Lancelot and Tristan are called the two greatest knights and greatest lovers by Merlin, and the fairness of the two ladies is often compared. The basic outline of their tales is similar in that both knights are caught in a dangerous triangle of emotion that pits their love for their ladies against their loyalty to their king. The stories of the pairs are not, however, merely variations on a theme; there are notable contrasts between the two tales, not the least of which is the disparity between the two kings involved-- the generally noble and good Arthur has little in common with the malicious Mark. Also of note is the choices that Malory makes in regards to each tale's ending. While the Lancelot and Guinevere pairing remains a major focal point throughout the work (to the degree that consequences of their relationship give rise to the main dramatic action of the Morte's ending), the Tristan-Isolde pairing dominates only The Book of Sir Tristram, which ends before Tristram's death at Mark's hands. The death, in fact, takes place off-screen, a side-note that comes up as a result of a reference to Sir Bellyngere le Bewse and Alexander the Orphan, who are named in the catalogue of knights that directly precedes the healing of Sir Urry. The dramatic death inherent in other versions is elided; here, Mark's treacherous attack on the unarmed harping Tristram is remarked upon only in passing, and readers are completely insulated from the heartbreak felt by a dying Tristram who believes that his love has abandoned him. By deflecting and downplaying the dramatic moment of the Tristram and Isolde material, Malory preserves the continuing tension of the Lancelot-Guinevere relationship, which is central to the overall trajectory of his narrative in a way that Tristram and Isolde's story is not.

Tristan and Isolt after the Middle Ages

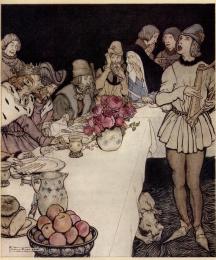

After Thomas Malory's fifteenth-century translation and adaptation of the Prose Tristan as part of his monumental Morte Darthur, English versions of the Tristan and Isolde love story undergo a nearly four-hundred year hiatus, during which the only references to the pair can be found in discussions of hunting terminology and passing uses of the name "Tristan," sometimes in reference to the Tristan of the famous lovers, and sometimes merely as a semi-Arthurian name. There only seem to have been two exceptions to this silence. One is a play by Thomas Downton, now lost, called The Booke of Trystram, the only record of which is found in Philip Henslowe's diary. 8 The other is a 1780 translation and abridgement of the Prose Tristan called Tristan, Son to King Melianus of Leonois by Lewis Porney, a Frenchman teaching in England. This work survives in a few copies, but has not had much attention from modern critics. In 1802, Tristan and Isolde again surface in a poem written by Sir Walter Scott which is attached to his discussion of Thomas the Rhymer in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. 9 Scott says that he wrote the poem in an "attempt to commemorate [Thomas] the Rhymer's poetical fame," and he sets his poetic summary of Tristan and Isolt's doomed love within a frame of Thomas of Ercildoune entertaining the Scottish court after a feast.

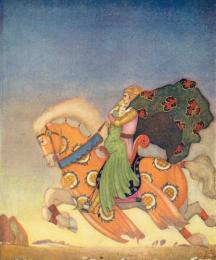

Following Scott's poem, the Tristan and Isolt legend had, like Arthurian material in general, a marked resurgence during the nineteenth century. Many of the new versions followed the main medieval model, telling the tale in poetic form rather than prose. The recastings, while they cannot be divided into the version courtoise and version commune of the medieval texts, do present widely varying interpretations of the lovers and their actions. Some retellings, such as Tristram and Iseult by Matthew Arnold and Tristram of Lyonesse by Algernon Swinburne, present the lovers and poor deceived Mark in a sympathetic light. Arnold's poem is also notable for its kind portrayal of the often-overlooked Iseult of Brittany, the woman whom Tristan marries and subsequently neglects, because he feels that his marriage is a betrayal of Iseult of Ireland. Others, such as Tennyson in his idyll The Last Tournament, are thematically darker. Tennyson's Tristram is callous and cruelly mirthful to everyone except Isolt, and she characterizes in many ways the appalling depths to which Arthur's court has fallen. His Isolt, although not accorded her own Idyll, can definitely be regarded as one of the wicked women exemplified in the series of poems. She is petulant and demanding, disdainful of Mark, and prideful towards Tristram, loving and hating irrationally and unevenly. In the twentieth century, many other authors, including such notables as Thomas Hardy, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Rosemary Sutcliff, Diana Paxson, John Masefield, and John Updike, took on the legend as well, each reworking the material in different styles and to different ends. A complete list of modern retellings can be found in the Bibliography of Tristan and Isolt in Modern Literature in English.

Given the lasting fascination of the material, it should come as no surprise that the legend was also used as a basis for various non-textual retellings, which range from the multitude of Tristan songs of the Medieval period to Richard Wagner's epic Tristan und Isolde to L'Eternel Retour, the disturbingly Aryan film adaptation made by Jean Delannoy and Jean Cocteau in 1943 in Vichy France. These last two adaptations are probably the best-known to modern audiences of all extant Tristan materials, though the most recent adaptation is the 2006 film Tristan + Isolde directed by Kevin Reynolds. Reynolds’ film attempts to historicize the legend, resulting in a story that not only passes off imaginative inventions as historical events, but also modifies the tale itself in ways that, it could be argued, considerably lessen its dramatic impact.

Footnotes1 McCann, 18-22.

2 Early French Tristan, v. 2, p. 9.

3 Sir Tristrem, lines 1693-94.

4 Casebook xxi.

5 Vinaver, 340.

6 Malory, 375, ll. 16-22.

7 Compare pp. 56-67 of the Prose

Tristan with pp. 393-96 of

The Book of Tristram de Lyones; the Prose

Tristan's long process of negotiating trysts is greatly compressed by Malory, who goes very quickly to the series of battles Tristan has before and after visiting Segwarydes' wife.

8 Nastali and Boardman, 26.

9 In his introduction to his poem "Thomas the Rhymer: Part Third," Scott mistakenly equates the "Thomas d'Angleterre" connected to the Tristan legend with Thomas of Ercildoune, also known as Thomas the Rhymer. See

note 2 in the Camelot Project edition of "Thomas the Rhymer: Part Third" for T. F. Henderson's discussion of the relationship between Thomas d'Angleterre's Tristan poem and

Sir Tristrem. Scott's attribution of

Sir Tristrem to Thomas of Erceldoune can be explained by a glance at the first two lines of the poem:

I was at Ertheldoun

With Tomas spak Y thare;

Ther herd Y rede in roune

Who Tristrem gat and bare,

Who was king with croun,

And who him forsterd yare,

And who was bold baroun,

As thair elders ware.

Bi yere

Tomas telles in toun

This aventours as thai ware.

The fact that the writer of

Sir Tristrem implies that Thomas of Erceldoune was the author does not mean that this is the case; medieval writers routinely invented lines of authority in order to legitimize their own compositions or retellings. See the

introduction to Lupack's edition for an in-depth discussion of the poem's probable origins.

BibliographyEarly French Tristan Poems. Ed. Norris Lacy. 2 volumes. Rochester, NY; Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer, 1998. [All included texts are facing page translations. Vol. 1 contains Béroul's Tristran and both the Oxford and Berne Folies Tristan; Vol. 2 contains the Tristran of Thomas of Britain, the Carlisle Fragment of Thomas of Britain's Tristran, Marie de France's Chèvrefeuille, and the anonymous poems Tristan Rossignol ("Tristan Nightingale") and Tristan Menestrel.]

Loomis, Gertrude Schoepperle. Tristan and Isolt: A study of the Sources of the Romance. 2 vols. Second ed., expanded by a bibliography and critical essay on Tristan Scholarship since 1912 by Roger Sherman Loomis. New York: Burt Franklin, 1963.

Malory, Thomas. "The Book of Sir Tristram de Lyones." In Vol. 1-2 of The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. 3 vols. Ed. Eugène Vinaver. Rev. P. J. C. Field. 3rd edn. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. Pp. 365-846.

McCann, W. J. "Tristan: The Celtic and Oriental Material Re-examined." See Tristan and Isolde: A Casebook. Pp. 3-35.

Nastali, Daniel P. and Philip C. Boardman. The Arthurian Annals: the Tradition in English from 1250 to 2000. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Sir Tristrem. In Lancelot of the Lake and Sir Tristrem. Ed. Alan Lupack. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1994. Pp. 143-277.

Tristan and Isolde: A Casebook. Ed. Joan Tasker Grimbert. New York; London: Garland Publishing, 1995.

Vinaver, Eugène. "The Prose Tristan." In Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages: A Collaborative History. Ed. Roger Sherman Loomis. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1959. Pp. 339-347.

Read Less