According to the bestiary tradition, deer are the enemies of

serpents (Clark 134). Deer also migrate, which the tradition glosses to explain that deer are like good Christians, who change their homes from the world to heaven (Clark 135). These moral attributes are generally absent from medieval Arthurian texts, though deer appear quite consistently in these works.

Deer feature most commonly as the object of hunts in medieval Arthurian texts, and there are numerous examples of these hunts. Often, these hunts are simply the means of getting the characters outside the physical spaces of castles and cities.

The Avowyng of Arthur features a description of the frequent hunting done by those at the court, and both bucks and harts are mentioned among the animals hunted (l. 26-27).

The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle opens with

Arthur hunting a hart. This hunt, though, seems to function primarily as the opening trope of the narrative, the means to get Arthur into the woods; it is on this hunt that he is found by Sir Gromer Somer Joure, and their meeting drives the rest of the plot. A hunt also opens

Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle;

Gawain &

Kay get lost in a mist and lose the deer they were hunting. In these instances, hunting deer serves as a way to place characters in liminal spaces in which encounters with the unfamiliar or mysterious can occur.

However, medieval Arthurian texts often describe the hunt for its own sake or for the sake of its own social importance. In Gottfried von Strassburg's

Tristan,

Tristan...

Read More

Read Less

According to the bestiary tradition, deer are the enemies of

serpents (Clark 134). Deer also migrate, which the tradition glosses to explain that deer are like good Christians, who change their homes from the world to heaven (Clark 135). These moral attributes are generally absent from medieval Arthurian texts, though deer appear quite consistently in these works.

Deer feature most commonly as the object of hunts in medieval Arthurian texts, and there are numerous examples of these hunts. Often, these hunts are simply the means of getting the characters outside the physical spaces of castles and cities.

The Avowyng of Arthur features a description of the frequent hunting done by those at the court, and both bucks and harts are mentioned among the animals hunted (l. 26-27).

The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle opens with

Arthur hunting a hart. This hunt, though, seems to function primarily as the opening trope of the narrative, the means to get Arthur into the woods; it is on this hunt that he is found by Sir Gromer Somer Joure, and their meeting drives the rest of the plot. A hunt also opens

Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle;

Gawain &

Kay get lost in a mist and lose the deer they were hunting. In these instances, hunting deer serves as a way to place characters in liminal spaces in which encounters with the unfamiliar or mysterious can occur.

However, medieval Arthurian texts often describe the hunt for its own sake or for the sake of its own social importance. In Gottfried von Strassburg's

Tristan,

Tristan is brought to Mark of Cornwall's court when he is found by huntsmen; Tristan earns the king's attention due to his considerable knowledge of hunting lore. He teaches the huntsmen to excoriate a hart that has been captured and killed, so it can be returned to the court. von Strassburg's text provides a detailed description of Tristan as he cuts the hart into pieces and detaches them so they can be carried (40-42). King

Mark, who does not yet know he is Tristan's uncle, is so impressed that he makes the fourteen year old Tristan his huntsman-in-chief (47). (The Middle English

Sir Tristrem reimagines this slightly; in this version, Tristrem dresses an unidentified beast before several of Mark's men, and his skill earns him a position carving meat in Mark's household (169-70).) Later in von Strassburg's version of Tristan, Mark and his party go out hunting and discover a strange hart, described as "maned like a horse, strong, big, and white, with under-sized horns scarce renewed" (227). While the party is pursuing this strangely-formed hart, the master huntsman discovers Tristan and Isolde, sleeping some distance apart with Tristan's sword between them; the huntsman calls Mark, and yet another reconciliation between Mark and Isolde occurs (232). The importance of deer to hunting practice is perhaps nowhere more obvious than in

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which features lengthy descriptions of how deer are hunted, killed, and dressed. Distinction is made in

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as to which deer are acceptable to hunt: "ϸay let ϸe herttez haf ϸe gate, with ϸe hyзe hedes, / ϸe breme bukkez also, with hor brode paumes; / For ϸe fre lorde hade defende in fermysoun tyme / ϸat ϸer schulde no mon meue to ϸe male dere. / ϸe hindez were halden in with 'Hay!' and 'War!' / ϸe does dryuen with gret dyn to ϸe depe sladez" (l. 1154-1159). Due to the time of year, the male deer (bucks and harts) are not in season; only the female deer (hinds and does) are restrained to be hunted. The romance later includes a lengthy description of field dressing the slaughtered deer and transporting them to the castle, where Bertilak gives them to

Gawain as their agreement demands (l. 1319-1365). This hunting, interspersed with Gawain's exchange with the lady, is also found in

The Greene Knight, in which the Green Knight kills several does while Gawain earns kisses from the lady (l. 406-409). These detailed descriptions have been used by scholars as evidence of medieval hunting practices. Deer were closely linked to the hunt, and medieval people “at least had the concept of conservation of sustainable deer populations”: both Henry III and Henry VII suspended deer hunting in particular forests in order to sustain the population (Aberth 189). Hunting ritual of the kind done by Tristan and other figures of Arthurian romance was likely the exclusive purview of noble hunters, since only they would have had time and leisure for such practices; indeed, records suggest that deer were sometimes netted or slain by other effective (if not noble) means (Aberth 197).

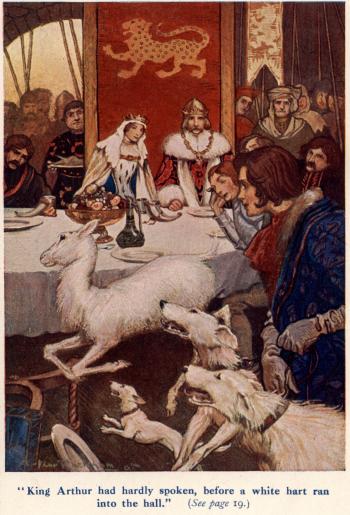

Yet these hunts for deer are not always as literal as the above instances suggest. The white stag appears on several occasions in medieval Arthuriana; early in Malory, it is one of the three creatures that run through the hall during Arthur's marriage feast in the Tale of King Arthur (1.102). A white hart comes into the hall, followed by a white

brachet, and they are chased in turn by a pack of hounds. Gawain is tasked with capturing the white hart, and though he succeeds, he also kills a lady, which leads to his oath that he will champion the causes of ladies in the future (1.105-109). The quest sparked by the hart and these other creatures leads to the Pentecostal oath so critical to the chivalric virtues practiced by Arthur's court (1.120). Chretien de Troyes's

Erec and Enide opens with Arthur's intent to revive the custom of the white stag, which Gawain explains is that "whoever can kill the white stag has the right to kiss the most beautiful maiden of your court regardless of the consequences" (2). Arthur successfully kills the stag, but the kiss itself is fortunately delayed until Erec returns to court with Enide, who is immediately recognized by all as the most beautiful lady there (23). Her arrival thus prevents dissention at court. Michael Twomey identifies this as the earliest appearance of the white stag in the Arthurian tradition. In this appearance, he suggests, "the significance of the hunt is the affirmation of chivalric and courtly order, which is temporarily jeopardized” (100). This story is also retold in the Post-Vulgate Merlin Continuation (4.227).

Deer – particularly white deer – often appear in religious contexts, both in Malory and in the French Grail cycle. In Malory's

Morte d’Arthur, Galahad and the grail knights encounter a hart and four lions while in the Waste Forest. The lions are transformed into a

lion, a man, an eagle, and an ox – signs of the evangelists – while the hart leaps through a glass window without breaking it. The hart here is explained as a symbol of Christ entering the Virgin Mary’s womb (2.999). The white stag in the Lancelot-Grail Cycle's

Queste is glossed differently: in this version,

Galahad,

Perceval, and

Bors track a stag into a chapel, and they find the stag being protected by four lions. The knights marvel as the stag turns into a man, while they lions turn into the symbols of the four evangelists (the lion, man, eagle and ox, as in Malory). The hermit singing mass tells them that this reveals them to be worthy men, as God is letting them see his mysteries, and explains that the stag represents the resurrection of Christ through its rebirth (4.74). This is also retold in the Post-Vulgate Quest (5.236). In the Post-Vulgate Merlin Continuation, Dodinel, Galahad, and

Yvain encounter a white stag being guarded by four lions. They marvel at this wonder, and then Galahad rides off in pursuit of the stag (though without finding it) (5.136). Though this hunt is not technically part of a Grail Quest, the choice of Galahad as the knight who pursues the stag seems meant to invoke these quests where the stag appears to him. These hunts are not unique to medieval Arthuriana; as Twomey observes, “the stag hunt, particularly the hunt for a white stag, has various significances in classical and medieval literature, and it occurs in a variety of genres, such as myth, Breton lai, saint's life, chanson de geste, and romance” (100). The persistent use of the white stag in grail quests, especially French ones, suggests that these deer lead the knights of the grail quest to new knowledge or truth.

Deer appear across a range of Arthurian works and fulfill both practical and symbolic functions. While work has been done on these creatures, particularly the motif of the white stag, much fascinating research remains to be done on Arthurian deer.

BibliographyTwomey, Michael W. "Self-Gratifying Adventure and Self-Conscious Narrative in 'Lanceloet en het Hert met de Witte Voet.'" Arthuriana 17.1 (Spring 2007): 95-108.

For all other works cited, see the Critical Bibliography for the Arthurian Bestiary.

Read Less