One of the most frequently represented characters in Arthurian literature, Kay has never starred in his own romance. He is not a heroic figure: constantly presented as a hot-tempered, sharp-tongued fellow, he is generally abusive to those whom he perceives as weaker than himself. In romances, Kay is tolerated by the rest of the Round Table because his loyalty is never in question, and he is generally portrayed as Arthur’s foster-brother, giving him a familial connection to the king and prominence in Arthur’s esteem. But he is almost always disliked, despite his early heroic appearances.

Kay has not always been an unpleasant figure. His origins in Welsh literature portray him as Arthur’s equal, a heroic figure whose deeds border on the super-heroic. For example, in

Culwch and Olwen, Kay can hold his breath for nine days and nine nights, and he defeats a giant through trickery, cutting his head off in one blow. His loyalty to Arthur is clear in these early tales, even when he questions Arthur’s leadership, and this loyalty is probably the sole trait that has remained with the character to the present. Linda M. Gowans describes his early character as "mocking, savage and a terrifying opponent in battle" (

Cei and the Arthurian Tradition, 8) -- all positive qualities for a character in early medieval literature. Indeed, he is one of Arthur’s most capable and loyal companions in

Culwch and Olwen, as well as in many early, Celtic poems, where he is often paired with Bedwyr (later Bedevere) and Gwalchmai (later

Gawain).

In the chronicle tradition, including Geoffrey of Monmouth’s

The History of the Kings of Britain and the

Alliterative...

Read More

Read Less

One of the most frequently represented characters in Arthurian literature, Kay has never starred in his own romance. He is not a heroic figure: constantly presented as a hot-tempered, sharp-tongued fellow, he is generally abusive to those whom he perceives as weaker than himself. In romances, Kay is tolerated by the rest of the Round Table because his loyalty is never in question, and he is generally portrayed as Arthur’s foster-brother, giving him a familial connection to the king and prominence in Arthur’s esteem. But he is almost always disliked, despite his early heroic appearances.

Kay has not always been an unpleasant figure. His origins in Welsh literature portray him as Arthur’s equal, a heroic figure whose deeds border on the super-heroic. For example, in

Culwch and Olwen, Kay can hold his breath for nine days and nine nights, and he defeats a giant through trickery, cutting his head off in one blow. His loyalty to Arthur is clear in these early tales, even when he questions Arthur’s leadership, and this loyalty is probably the sole trait that has remained with the character to the present. Linda M. Gowans describes his early character as "mocking, savage and a terrifying opponent in battle" (

Cei and the Arthurian Tradition, 8) -- all positive qualities for a character in early medieval literature. Indeed, he is one of Arthur’s most capable and loyal companions in

Culwch and Olwen, as well as in many early, Celtic poems, where he is often paired with Bedwyr (later Bedevere) and Gwalchmai (later

Gawain).

In the chronicle tradition, including Geoffrey of Monmouth’s

The History of the Kings of Britain and the

Alliterative Morte Arthure, Kay remains a noble, able warrior. Geoffrey is the first to appoint Kay seneschal (chief steward of the household), a position of great responsibility and honor. Kay is also named count of Anjou, and he and Bedivere join Arthur in his combat against the giant of Mont Saint Michel. His death in Geoffrey comes from a mortal wound received on the battlefield, and he is laid to rest with proper ceremony.

However, in the French romances, starting with Chrétien de Troyes, Kay’s nature sours. Chrétien’s Kay is often verbally abusive, but this abuse is put to good end, as his vicious tongue prods young knights to prove themselves. For example, in

Yvain (The Knight with the Lion), Kay heckles

Yvain; the latter knight proceeds to prove himself by defeating Esclados, the Knight of the Fountain, which sets up the rest of the story. Similarly, Kay is responsible for instigating

Gareth’s quest, having sent Gareth (or "Beaumains") to the kitchen, which put him in a position to accept a quest for his lady (Lyonesse in Malory), making a name for himself in the process. As with Yvain and Gareth, Kay often spurs younger knights to go forth and prove him wrong by demonstrating their own worth.

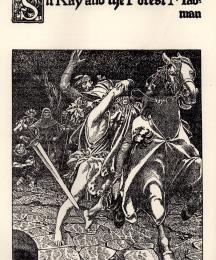

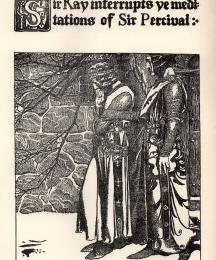

Often, Kay is repaid for his abuse -- in

Yvain, he fights Yvain, now the Knight of the Fountain, only to be swiftly unhorsed. Both Gareth and

Perceval repay his harsh words towards them or their ladies. And Kay is presented as a foil for Gawain in several romances, for example

The Carle of Carlisle,

Gologras and Gawain, and the

Awntyrs of Arthur, where Gawain’s courtesy offsets Kay’s rudeness to their host and saves the knights from death or dishonor.

Kay’s mean-spiritedness (and Arthur’s remarkable patience) has usually been presented without an explicit cause. One of the most intriguing, popular, and earliest explanations comes from Robert de Boron. In his

Merlin (

circa 1200), Kay and Arthur are first brought together in infancy, as

Merlin leaves Arthur to be fostered by Kay’s mother. Kay himself is suckled by a low-born woman, thus explaining (for medieval audiences) his offensive behavior: while Arthur is nourished by a noblewoman, Kay must make due with the inferior milk of a commoner. Robert de Boron strengthens the connection between Arthur and Kay later, when Kay’s father Antor asks Arthur to make Kay seneschal for life despite his rude personality, because these traits were received for Arthur’s sake. Centuries later, John Steinbeck reflects modern concerns by having Kay complain to Lancelot that numbers have made him disagreeable; as seneschal, he is responsible for running the court, and his attention to the details of feeding knights, ladies, and prisoners at the court has forced him to become a small, mean person. T. H. White, in

The Once and Future King, presents Kay as a spoiled child who hates to be second in anything; as a result, he grows up to be a selfish adult. But the most common explanation for Kay’s disposition is simply "tradition," as most authors do not discuss Kay’s childhood. He is indispensable as Arthur’s seneschal, as Chrétien emphasizes in his

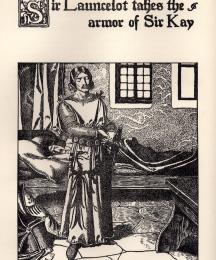

Lancelot (The Knight of the Cart).

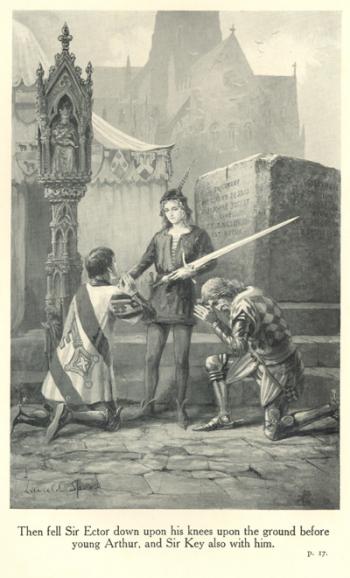

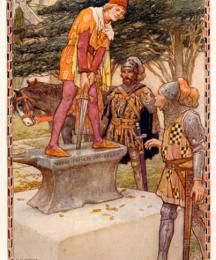

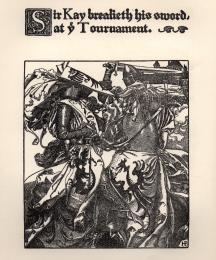

Later tales generally follow the French tradition, especially as retold by Malory, of ascribing a foul nature to Kay, although they vary greatly in degree. They often emphasize his status as the seneschal, who has duties that implicitly keep him at home. Kay often heads out on quests or participates in tournaments, usually to fail. It may be that his inability to succeed as an adventurous knight is tied to his position, because he is unable to train constantly, as do other knights. Most authors make him a difficult character to like. Sometimes he is simply a cranky figure used for comic relief; occasionally, he is treacherous and even murderous. The famous "sword in the stone" tale presents Kay as willing to take credit for Arthur’s freeing the sword, thus claiming the throne of England for himself. More villainously, in

Yder, Kay tries to poison the eponymous hero, and in the

Perlesvaus, Kay murders Arthur’s son Loholt as the latter sleeps and claims victory over Loholt’s slain opponent, a giant. While these truly evil presentations are few, they are consistent with Kay’s general character in romance: headstrong, self-aggrandizing, and resentful of his inability to successfully pursue knightly quests.

Some modern authors, such as Madison J. Cawein ("Morgan Le Fay," 1899), T. H. White (

The Once and Future King, 1958), and Phyllis Ann Karr ("The Idylls of the Queen," 1982) have tried to redeem Kay in various ways, but the power of tradition has forced him into an uncomfortable place, akin to the trickster of myth. Kay has become a necessary evil, a troublemaker, a figure whose vicious nature ultimately leads to the establishment of a name for young, untested knights (or the furtherance of the reputations of established knights such as Lancelot and Gawain). This is perhaps most obvious in Mike W. Barr’s

Camelot 3000, where Kay twice acts badly to help the fellowship: first, he insults Tristan to distract Gawain and Galahad (thus keeping them in New Camelot); and second, he betrays Merlin to spur the knights to action. He defends himself in both cases by pointing out the greater good, and Arthur forgives him his insult, but not the betrayal (a much graver misdeed).

Despite his negative portrayals, Kay’s position in Arthur’s court is assured, for he not only spurs complacent knights to action, but also shows Arthur’s loyalty to his friends and family. Authors seem to like presenting Kay because his lack of prowess highlights the heroics of the main characters of the works.

BibliographyClassen, Albrecht. "Keie in Wolframs von Eschembach Parzival: ‘Agent Provocateur’ oder Angeber?" Journal of English and Germanic Philology 87 (1988): 382-405.

Cor, M. Antonia. "The Role of Kay in the Perlesvaus." Medieval Perspectives 2.1 (1987): 177-83.

Dean, Christopher. "Sir Kay in Medieval English Romances: An Alternative Tradition." English Studies in Canada 9.2 (1983): 125-135.

Gowans, Linda M. Cei and the Arthurian Legend. Cambridge: Brewer, 1988.

Herman, Harold J. "Sir Kay, Seneschal of King Arthur’s Court." Arthurian Interpretations 4.1 (1989): 1-31.

Howey, Ann F. "A Churlish Hero: Contemporary Fantasies Rewrite Sir Kay." Extrapolation: A Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy 41.2 (2000): 115-26.

Huby, Michel. "Le Sénéchal du Roi Arthur." Études Germaniques 31 (1976): 433-37.

Miller, D.A. "The Twinning of Arthur and Cei: An Arthurian Tessera." Journal of Indo-European Studies 17 (1989): 47-76.

Volkmann, Berndt. "Costumiers est le dire mal: Überlegungen zur Funktion des Streites und zur Rolle Keies in der Pfingstfestszene in Harmanns Iwein." In Bickelwort und wildiu maere: Festschrift für Eberhard Nellman zum 65. Geburstag. Ed. Dorothee Lindemann, Berndt Volkmann, and Klaus-Peter Wegera. Göppingen, Germany: Kümmerle, 1995. Pp. 95-108.

Whetter, K.S. "Reassessing Kay and the Romance Senseschal." Bibliographical Bulletin of the International Arthurian Society/Bulletin Bibliographique de la Société Internationale Arthurienne 51 (1999): 343-63.

Read Less