Boars are described in the bestiary tradition as fierce creatures (152), though no moral is prescribed to them. While boars serve several functions in medieval Arthuriana, the ferocity ascribed to them in the bestiaries is a consistent element of their appearances in Arthurian works.

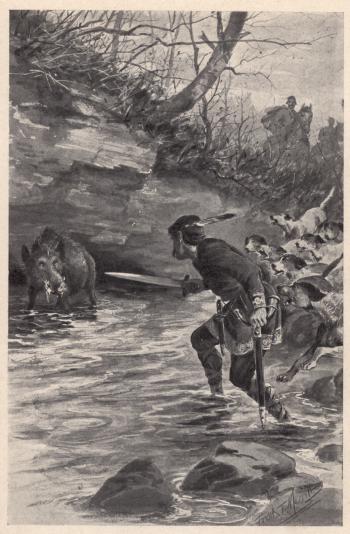

Boars appear most frequently in hunts, and, often, they injure even the best knights of the court. In the Prose

Lancelot,

Lancelot is exiled from court by Guinevere and loses his mind. Though a hermit cares for him, Lancelot leaves the hermit's home and pursues a boar; he is gravely injured in the hunt. He is found by another hermit and brought to King Pelles's court, where he is healed. This adventure leads to the restoration of his sanity (3.332-3), so the boar wound is essential to the rest of the romance's plot. This story is retold in the Post-Vulgate

Merlin Continuation (5.68). In Malory's "Book of Sir Tristrem de Lyones," Lancelot pursues a boar and kills it, though he is injured in the thigh before he can chop off the boar's head; as in the Prose

Lancelot, he is brought to King Pelles's court to recover and is recognized there (2.821-24). These wounds are essential to the plot, but it is interesting to observe that boars are fierce enough to injure one of Arthur's greatest knights.

A boar similarly injures

Tristran in Beroul's version of the Tristran story, but the effect of the wound is different. Beroul includes an episode in which

Mark and a dwarf attempt to catch Tristran going to Iseult's bed by placing flour between their beds, so Tristran's steps would be seen if he tries to join her in bed. Tristran...

Read More

Read Less

Boars are described in the bestiary tradition as fierce creatures (152), though no moral is prescribed to them. While boars serve several functions in medieval Arthuriana, the ferocity ascribed to them in the bestiaries is a consistent element of their appearances in Arthurian works.

Boars appear most frequently in hunts, and, often, they injure even the best knights of the court. In the Prose

Lancelot,

Lancelot is exiled from court by Guinevere and loses his mind. Though a hermit cares for him, Lancelot leaves the hermit's home and pursues a boar; he is gravely injured in the hunt. He is found by another hermit and brought to King Pelles's court, where he is healed. This adventure leads to the restoration of his sanity (3.332-3), so the boar wound is essential to the rest of the romance's plot. This story is retold in the Post-Vulgate

Merlin Continuation (5.68). In Malory's "Book of Sir Tristrem de Lyones," Lancelot pursues a boar and kills it, though he is injured in the thigh before he can chop off the boar's head; as in the Prose

Lancelot, he is brought to King Pelles's court to recover and is recognized there (2.821-24). These wounds are essential to the plot, but it is interesting to observe that boars are fierce enough to injure one of Arthur's greatest knights.

A boar similarly injures

Tristran in Beroul's version of the Tristran story, but the effect of the wound is different. Beroul includes an episode in which

Mark and a dwarf attempt to catch Tristran going to Iseult's bed by placing flour between their beds, so Tristran's steps would be seen if he tries to join her in bed. Tristran outsmarts them by leaping over the flour, but as a result, a wound he received the day before from a boar breaks open and leaves blood in the flour around the bed (35). While Lancelot's encounters with boars lead to his recognition and healing, Tristran's injury nearly causes him to be caught cuckolding his uncle.

The ferocity of boars makes them a challenge for hunting knights in many works. The

Avowyng of Arthur features a description of the frequent hunting done by those at the court, and boars are mentioned as one of the animals hunted (l. 26). One particularly ferocious, destructive boar is the focus of much of the text:

Arthur,

Kay,

Gawain, and a knight called Bowdewynne of Bretan go to Inglewood forest in search of it (l. 74-6), and the poem discusses at length the boar's challenge to Arthur. Though the battle is fierce, Arthur eventually kills the boar some 300 lines after it first appears. In the Prose

Lancelot, Arthur is captured by the false

Guinevere when he is lured out of the castle on a boar hunt (2.262). These instances suggest a particular link between these creatures and the adventures that shape the plots of both narratives.

Though boars are difficult to hunt, they are a worthwhile target; the second creature hunted by Sir Bertilak and his party in the anonymous

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a boar, and it takes the party some time to successfully kill the fierce creature; the boar foams at the mouth and makes the hunting knights fear him (lines 1572-76). They cut off its head and return to the castle with it as a trophy, and the rest of the boar's meat is cooked for the evening meal (266-67). This scene is interspersed with Gawain's flirting with Lady Bertilak, specifically his earning of kisses. This hunt is thus part of the escalating series of hunts and flirtations that structure much of the romance. Moreover, if one reads this interspersion of scenes as indicative that Lady Bertilak is also engaged in a type of hunting, as Lynn Arner suggests, then the romance depicts Gawain himself as the dangerous, cornered boar ("Ends of Enchantment," 89-90).

1

Boars are also hunted in the

Mabinogion, where killing such a creature is a fairy-tale like test. For example, in

"Kilhwch and Olwen," Kilhwch must hunt the boar Trwyth as one of his tasks to win a bride. In "Manawyddan the Son of Llyr," Pryderi and Manawyddan (who is identified in other Welsh materials as one of Arthur's retinue) hunt a pure white boar, which leads to the magical disappearance of Pryderi, the impetus for the rest of the plot. In these examples from the Mabinogion, unlike in the earlier more directly Arthurian examples, the boar is not just a creature to hunt or the impetus for an adventure (as in many of the above French and English romances), but also an obstacle in the hero's path and an essential element in the plot.

Boars may also represent characters in prophetic dreams. Arthur dreams of a

dragon (a common symbol for Arthur) defeating a boar in Caxton's edition of Malory's

Morte d'Arthur, and a philosopher explains to Arthur that the dream predicts Arthur's victory in the upcoming battle (124). (In the Winchester manuscript, the creature in question is a

bear, rather than a boar.) In von Strassburg's

Tristan and Isolde, Tristan's companion Marjodoc dreams of a boar that runs to Mark's court from the forest and attacks everything in its path, including the king's bed, while none of Mark's courtiers intervene. Waking up in a fright from this dream, Marjodoc discovers Tristan in bed with Isolde (179). Marjodoc's dream foretells his discovery, and it is particularly interesting because the havoc wreaked by the boar emphasizes the destructiveness of Tristan and Isolde's relationship in Mark's court.

Boars are frequent in hunting scenes and are fierce enough to seriously injure knights. Knights' interactions with boars are often crucial elements in the larger plots of these works; a fight with a boar may lead to capture or recognition, as with Lancelot and Tristan, or a hunt might be one task in a series as a knight strives for some larger goal, as in the

Mabinogion. These varied appearances of boars demonstrate how encounters with animals play a dramatic part in medieval Arthurian works.

Pig

Though they are obviously related to boars in some way, references specifically to pigs in medieval Arthuriana are less frequent. In contrast to boars, pigs seem to be associated with women, particularly treacherous ones. In the Vulgate Cycle’s

History of the Holy Grail, Hippocrates points out a sow to his wife, telling her that anyone who ate it that day would die. The lady secretly orders that the pig be cooked and served to Hippocrates, due to her anger that she was forced to marry him. He dies from the pig meat, freeing her of her marriage (1.106).

In the Vulgate Cycle's

Story of Merlin,

Merlin transforms himself into a stag and goes to Rome, where he tells Julius Caesar that he will learn nothing about a dream he has had until he finds the Wildman. That Wildman is also Merlin, who lets himself be captured and brought to the emperor so he can interpret his dream (1.324). The emperor dreams of a great sow, who lies with twelve different wolf cubs; this dream, he explains, is proof that the emperor's wife is unfaithful (1.326). (The empress is unflatteringly represented by the sow.)

FootnotesAs Arner observes, "As the cross-cutting between the hunting and the bedroom scenes indicates, Lady Bertilak preys aggressively upon Gawain, an unseemly manner in which to treat a guest."

BibliographyArner, Lynn. "The Ends of Enchantment: Colonialism and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." Texas Studies in Literature and Language 48.2 (2006), 79-101.

For more information about the version of works cited, see the Critical Bibliography for this project.

Read Less