Read Less

Like many characters in the Arthurian legends, Morgan le Fay has been consistently transformed and interpreted by authors and artists for nearly a millennium. Her character and her narrative significance have varied widely from text to text, and while no easy description of these changes can be made, some general trends and developments can nevertheless be observed.

Celtic Origins

Morgan le Fay likely originated in Celtic mythology (Welsh in particular). Because the Morgan of medieval romance and legend is often presented as the wife of King Urien and the mother of Yvain, some have linked her to the the Welsh goddess Modron, who is described in the Welsh Triads as the daughter of Avallack, wife of Urian of Reghed, and mother of Owain. Scholars such as Norris Lacy and Lucy Allen Paton assert that these connections all but prove that she is descended from the Welsh Modron, and that her name may also have come from the folklore of Brittany (where certain fairy-sprites are referred to as "mari-morgans"). Another popular theory on Morgan's Celtic origins is that she is based upon the Irish battle-goddess Morrigan. There is, however, little textual evidence to support this theory, though the similarity of the names and Morgan's unpredictable (and often inimical) behavior in the later medieval tradition are vaguely correlative to the depiction of the Morrigan. In sum, it is possible that Morgan le Fay originated out of some type of Celtic goddess figure, and that such a tradition can be found, at least in glimmers, even into the fourteenth century

Gawain-poet’s work (who refers to her as a "goddes" in

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight); however, the specific goddess (or goddesses) from which the character is descended will likely never be known absolute certainty. . . .

Geoffrey of Monmouth

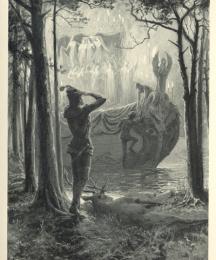

The earliest known reference to "Morgan le Fay" can be found in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s

Vita Merlini (c. 1150). Geoffrey provides a detailed description of Morgan in the

Vita: she is the fairest of nine otherworldly sisters; she shape-shifts, flies, and is

not (in contrast to other versions) on the barge with the dying Arthur. Geoffrey may be the first to write of her as a healer, a role she frequently occupies in later versions of Arthur's death. Morgan also appears in Layamon’s

Brut (c. 1150-55), a work directly inspired by Geoffrey's writings, and — though she is know in the

Brut as Argante

— she is virtually identical to the Morgan in Geoffrey's

Vita.

Morgan's Avalon in the Vita might be drawn from memories of classical mythological locales; the Isle of the Hesperides, for instance, is where either a lone tree or an orchard of immortality-giving apples grow and are tended by nymphs. Nevertheless, Morgan’s Avalon might also have developed out of accounts of Mannanan’s island of apples; Mannanan is, in fact, the ferryman who transports Arthur to Avalon in the Vita, and he is associated with Emhain Ablach, "a paradisiacal island that is usually identified with the isle of Man" (Dixon-Kennedy 195). Additionally, a possible connection exists between Morgan's realm described by Geoffrey an account by Pomponius Mela — a Roman geographer and author of de Chorographia – of the isle of Sena off the coast of Brittany (now known as Sein). Pomponius states that the isle

famous for the oracle of a Gaulish god, whose priestesses, living in the holiness of perpetual virginity, are said to be nine in number. The Gauls call them Senae, and they believe them to be endowed with extraordinary gifts, to rouse the seas and the wind by their incantations, to turn themselves into whatsoever animal form they may choose, to cure diseases which, among others, are incurable, to know what it is to come and to foretell it. They are, however, devoted to the service of those voyagers only who have set out on no other errand than to consult them. (as cited by Paton, 43-44)

Given the striking similarities between Geoffrey's account of Avalon and of Morgan and Mela's accounts of Sena and of its inhabitants, it is possible that Geoffrey drew from Mela's descriptions, in addition perhaps to Celtic and classical mythology, in crafting his descriptions of Morgan and Avalon. There is, however, little proof that a version of Pomponius Mela's work would have been available to him, and so this theory — while certainly of interest — should be approached with some caution.

Medieval French Literature

Chrétien de Troyes is likely the first to name Morgan as Arthur's sister. She appears — or is referred to — as an otherworldly healer in both Erec and Enide and Yvain. In both romances, the eponymous heroes are healed of their wounds through a magical potion of Morgan’s. Additionally, in Erec, Morgan is the lover of Guingemart, lord of Avalon — a somewhat anomalous figure given the the fact that women typically rule the isle in Arthurian literature; in Erec, she dwells either in Avalon with Guingemart or in an equally mysterious realm known as the Perilous Vale.

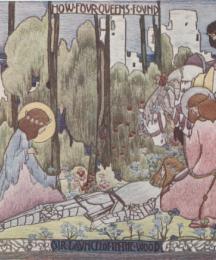

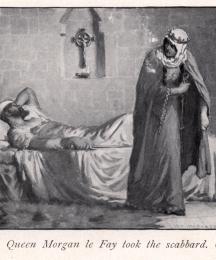

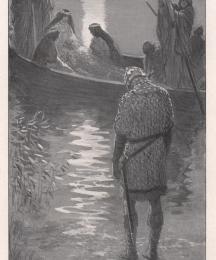

While Chrétien maintains Morgan’s benevolent characterization, French prose works represent her in more negative ways (Thompson 329). The Vulgate Cycle, in addition to embellishing her insidious behavior, provides the earliest "complete story" of Morgan. According to the Cycle, she is born of Igerne, and, though her father is likely Gorlois, she is at one point referred to as a bastard (Lancelot-Grail, ed. Lacy, vol. 1, 207). She is fostered and sent to a nunnery where she learns healing, reading, writing, and astrology. Merlin teaches her the magic arts while Arthur is engaged in the Saxon wars, and she eventually becomes the lover of Guiomar; he is Queen Guinevere's cousin and resembles Morgan's lover mentioned in Chrétien's Erec. The queen, according to the Cycle, ends the relationship between Morgan and Guiomart, and Morgan hates Arthur and Guinevere from this point onwards. Her hatred either intensifies or inspires her love for Lancelot, who declines her affections; as a result, she attempts to expose the love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere. She also creates the Valley of No Return where she entraps various warriors; Lancelot is captured there a total of three times. Despite these attempts to undermine Arthur’s court, she is, quite inexplicably, the one who takes Arthur away for healing (Bruce 368).

Morgan is cast in an almost identical light in the prose Tristan, where she consistently attempts to undermine and destroy Guinevere. In one instance, Morgan sends chastity-revealing drinking horn to Arthur’s court in an attempt to expose the queen’s infidelity. The horn is rerouted, however, to Mark’s castle, where Iseult and Tristrem are "outed" instead.

Post-Vulgate works such as the Suite du Merlin (or the Huth-Merlin) further develop and alter certain aspects of Morgan's story, and these alterations are best summarized by Christopher Bruce in the Arthurian Name Dictionary:

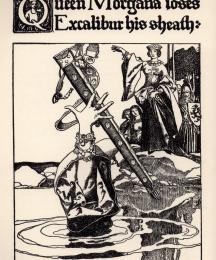

The Suite du Merlin, the other Post-Vulgate romances, and the Prose Tristan add and change the following facts: She married King Urien, and she had a son by him named Yvain. She later tried to murder Urien but was stopped by her son. Merlin fell in love with her. After she learned Merlin’s magic, however, she scorned him and threatened him with death if he ever came near her again. In addition to her other plots against Arthur, she made a counterfeit of Excalibur and its scabbard, giving the original to her lover, Sir Accalon of Gaul, while returning the fake one to Arthur. She then arranged for Arthur and Accalon to meet in combat, and it was only through the intervention of Nimue (the Lady of the Lake) that Arthur survived. Afterwards, Morgan managed to throw Excalibur’s scabbard into a lake. She sent a mantel to Arthur that would have burned him to cinders had he put it on, but Arthur made her unfortunate servant don it instead. . . . It was from Morgan that Mordred learned of the affair between Lancelot and Guinevere. She had a number of lovers, including Helians, Kaz, Gui, and Corrant. Despite her evil deeds, she again bears her brother’s body away from the last battlefield for healing. (368)

Medieval Insular Literature

High and late medieval literature in England recreates the villainous characterization of Morgan in the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate works. In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Bertilak of Hautdesert (The Green Knight) reveals that Morgan le Fay orchestrated the entire adventure:

Through the power of Morgan le Fay, who lives under my roof,

And her skill in learning, well taught in magic arts,

She has acquired many of Merlin's occult powers

For she had love-dealings at an earlier time

With that accomplished scholar, as all your knights know at home.

Morgan the goddess

Therefore is her name;

No one, however haughty

Or proud she cannot tame.

She sent me in this shape to your splendid hall

To make trial of your pride, and to judge the truth

Of the great reputation attached to the Round Table.

She sent me to drive you demented with this marvel,

To have terrified Guenevere and caused her to die . . .

That is she who is in my castle, the very old lady,

Who is actually your aunt, Arthur's half-sister,

The duchess of Tintagel's daughter, whom noble Uther

Afterwards begot Arthur upon, who is now king.

(ll. 2446-2460, 2462-2466. Trans. Winney)

This passage not only claims that Morgan's wields otherworldly magical powers, but also credits Merlin with having possessed them originally; in doing so, the author seems to conflate her with Niniane (or Viviane), who is more often described as the woman who "had love-dealings" with Merlin and acquired his powers. Additionally, Bertilak calls her a goddess, a description that — as mentioned earlier — has led certain scholars to believe she stems from Celtic mythology.

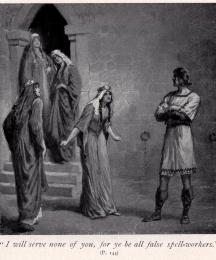

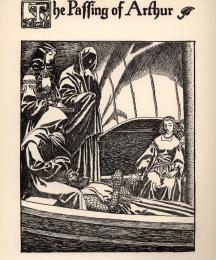

Many Vulgate and Post-Vulgate episodes were woven by Malory into his Morte D’Arthur, and the episodes involving Morgan are no exception. From her first appearance in the text she is associated with magic; she studies necromancy in the nunnery where she was schooled, a moment that could be interpreted as an attempt to subvert the Christian domain into which she has been placed. She is wed to Uriens, takes Accolon as a lover, plots with him against Arthur, attempts to seduce and eventually entraps Lancelot, sows discontent at both Mark’s and Arthur’s courts, and is, in general, a relentless nemesis of Arthur until the end of the Morte, when she peaceably takes Arthur to Avalon. In a more direct manner than most other authors, Malory forges a dichotomous relationship between the Lady of the Lake and the sorceress Morgan. Both are supernatural, associated with water, and tied in vital ways to Arthur himself. The varying women who hold the title of Lady of the Lake in the Morte consistently ally with Arthur and in many cases defend him against Morgan (see the intervention with Accolon, for instance). And yet it is still Morgan who affectionately bears her dying brother away to Avalon. Perhaps Malory wished to refrain from denigrating her entirely; or perhaps he wished to follow the tradition of other writers and present a recognizable account of the death of Arthur. Regardless, Morgan remains even into the fifteenth century an enigmatic character replete with paradoxical actions and motivations.

Post-Medieval Representations

As is the case with most Arthurian characters, there are few major appearances of Morgan in literature dating between the Middle Ages and the "renaissance" of Arthurian literature in the Victorian Era. One notable exception, however, is the reference to Morgan in Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso (1516). In Canto VI, the character Ruggerio stumbles upon a talking myrtle tree who, as it turns out, was originally a French paladin by the name of Astolpho. The former paladin tells of his travels and how he was taken as a lover — and ultimately turned into a tree — by the enchantress Alcina, a sister and ally of Morgan la Fay (Canto VI, 38). He tells Ruggerio that Morgan and Alcina are at war with their sister Logistilla. Logistilla is their father's only legitimate offspring and is therefore his heir:

At length we reached this lovely island that she

usurped from one of her sisters, their father's [Uther's] heir,

and the only legitimate daughter, apparently.

Alcina and Morgana, although quite fair

to look at are both wicked as they can be,

and the products, I'm told, of incest, and they share

a hatred of the third one. They have attempted

to drive her from the island and have preempted

more than a hundred towns, and have invaded

her holdings many times. She, who is called

Logistilla, has been in this conflict aided

by geography, . . . .

. . . Nevertheless,

her sisters do what they can to cause her distress

because they are vicious and she is a model of virtue,

chaste, and holy, the kind of woman who must

arouse their hatred and envy. Goodness can hurt you

when the people around you are wicked and unjust. (Canto VI, 44-6)

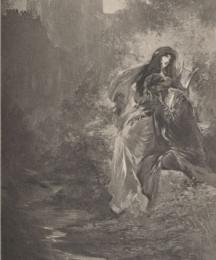

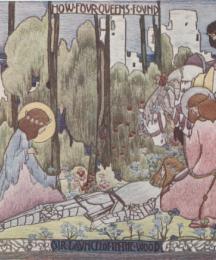

But while the Arthurian materials from the sixteenth through the eighteenth century generally have few references to or direct appearances of her, Morgan appears consistently in the upswell of Arthurian writings in the Victorian Era. In "Ogier the Dane" (1919), William Morris casts her as the lover or consort to the eponymous hero. Sir Robert Charles in his poem "Lancelot and the Four Queens" (1881) predictably casts Morgan as the central villain. Reginald Heber, in his "Morte d'Arthur: A Fragment" (1830), casts her as an enchantress-spirit and mother of Mordred. In general, Victorian writers present Morgan as either a simplistic or complex villain; she is rarely, if ever, cast in overtly sympathetic or positive terms.

American authors of the 19th and early twentieth century cast her in an almost identical light. Madison J. Cawein’s poem "Morgan le Fay" tells of how Morgan lures Sir Kay to her castle and how he is killed there by a hundred dead knights. Howard Pyle, in his North Folk Legends of the Sea, states that Morgan is "sister of King Arthur and the daughter of Pendragon," a striking departure from her typical presentation as the daughter of Gorlois, who was killed by Uther Pendragon. Pyle describes her as "a strange half-malevolent, half-benign enchantress, who dwells in the enchanted Isle of Avalon" (184). He also mentions the Fata Morgana — the mirage of an island that appears to sailors — and says that when sailors see the vision they are actually seeing Avalon itself "a golden land that he may indeed behold, but may never hope to attain" (184).

But while both British and American authors frequently reference her in their Arthurian works, the most memorable rendering of Morgan is perhaps that created by Mark Twain in his Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. He casts her as a villain, but a beautiful and cunning one imbued with a mystique likely inspired by earlier representations. This mystique, however, is due not to any actual magical properties, but is one strictly of her own cultivation:

. . . I knew Mrs. Le Fay by reputation, and was not expecting anything pleasant. She was held in awe by the whole realm, for she had made everybody believe she was a great sorceress. All her ways were wicked, all her instincts devilish. She was loaded to the eyelids with cold malice. All her history was black with crime; and among her crimes murder was common. I was most curious to see her; as curious as I could have been to see Satan. To my surprise she was beautiful; black thoughts had failed to make her expression repulsive, age had failed to wrinkle her satin skin or mar its bloomy freshness. (A Connecticut Yankee, 62)

The Modern Morgan

Twentieth and twenty-first century writers have complicated Morgan's character in part by reaching back to earlier accounts in which she was not an unequivocally antagonistic figure. Some modern works even conflate Morgan with Morgause, casting her as the mother of Mordred, as can be seen in both Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Mists of Avalon and in John Boorman's movie Excalibur. One of the most interesting modern portrayals of Morgan appears in Thomas Berger's Arthur Rex where, after a life devoted to evil, she decides to become a nun because of her belief that "corruption were sooner brought amongst humankind by the forces of virtue" (453). Contrastingly, Morgan becomes a defender of good in modern stories like Roger Zelazny's "The Last Defender of Camelot" and Sanders Anne Laubenthal's Excalibur, and Barbara T. Lupack's The Girl's King Arthur: Tales of the Women of Camelot. Lupack's short story tells of her constant faithfulness and loyalty to Arthur and reveals that all of the deeds she is accused of committing — from the theft of Excalibur and its scabbard, to treasonous plottings with Accolon — were, in fact, the doings of Morgause and Mordred. Morgan is falsly accused of treachery and banished from the court because of Mordred's machinations; however, she ultimately proves herself faithful to Arthur by bearing him away to Avalon at the conclusion of the tale.

Marion Zimmer Bradley, in The Mists of Avalon, creates a rounded character by combining the virtues, vices, and enigma found in the many medieval accounts of Morgan le Fay. In Mists, Morgan is introduced as an impressionable girl caught between Christian and pagan worlds. She develops into a powerful pagan priestess, eventually becoming High Priestess of Avalon. This role places her in active conflict with Arthur, who had come to side — despite his pagan initiation rites — with the Christians in his court. Her subversive actions are thus explained — though not always justified — as an extension of her position as a defender of the Old Ways. This book has wielded tremendous influence on more recent depictions of the Arthurian legend. As mentioned previously, it is she who gives birth to Gwydion (Mordred), the progeny of her incestuous sexual encounter with Arthur during his final pagan initiation rite. She does, as in so many other accounts, bear the dying Arthur away to Avalon toward the end of the book. Mists concludes with the elderly Morgan speaking in disguise with a small group of young nuns, realizing and accepting — over the course of this encounter — that her goddess is being worshipped in simply a new form: the Virgin Mary.

Whereas The Mists of Avalon is told largely from Morgan's perspective, Fay Sampson's Daughter of Tintagel novels are each narrated by a different character, each of whom possesses a unique and fraught perception of and relationship with Morgan; theirs are lives dramatically affected — and oftentimes destroyed — by their connections to her. The divide between Christian and Pagan is actively played upon in Sampson’s books as it is in Bradley’s work; however, the descriptions of the pagan ways are far less detailed and developed (and therefore less overtly neo-pagan) in Sampson's novels than they are in Bradley's. Rather than possessing a deep contempt for Chrisitanity as Bradley's Morgan seems to have, Sampson's Morgan deeply explores both pagan and Christian faiths in order to seek out and acquire the powers that might be found there.

The first book, Wise Woman’s Telling, is told by Morgan's nurse, Gwendolen – a wise woman and a pagan who tells of Morgan’s unhappy childhood. The second work, White Nun’s Telling, is told by Luned, the young nun assigned to be Morgan’s care-giver; Luned is ejected from the Tintagel nunnery at book’s end because she has fallen back into the Old Ways due to her association with Morgan and, among other infractions, finding herself pregnant after the Samhain festival. The third book, Blacksmith’s Telling, is told from the perspective of Telio, a pagan blacksmith cursed to live as a woman after running afoul of Morgan who is, at this point, wife to the much younger King Uriens. The fourth work, Taliesin’s Telling, is told from the perspective of the eponymous bard; he has journeyed to the court of Uriens and Morgan hoping to write a great song of the feats of Arthur. Instead, he learns that Arthur slept with his own sister Morgause (from which Mordred was born) and witnesses Arthur's undoing. The final book, Herself, is told from Morgan's perspective and jumps between her version of her life's story and an exploration of the sources that mention her.

Whereas modern novels have tended to complicate the idea of Morgan as a villain, the Marvel Comic world has preferred, in its presentations of Morgan, to mirror the arc from healer to villainess seen in medieval texts. In her earliest appearances, she is a favored priestess of Gaea and a healer who has a falling out with Merlin when he shifts his allegiance away from Gaea. This contention results in a six-day battle between the two of them on Samhain night – Merlin is refused entry into the sacred grove on Avalon by Morgan, and the two proceed to cast spells on one another. In other installments, her hatred for Arthur is greatly emphasized and she consistently plots against him – partially because of his father’s illicit relationship with their mother Igraine, and in part because of his promotion of Christianity over Celtic-goddess worship. DC Comics' Camelot 3000 shares much with the Marvel comic's depiction of Morgan as a villain – in the world of this graphic novel, Morgan returns as Arthur's old nemesis and plans an alien invasion of Earth.

In addition to her treatment in modern literature, Morgan le Fay appears – in various guises –in both television and film. In the film Excalibur (1981), for instance, she is conflated with both Morgause and with Nimue, and is presented as Arthur's constant nemesis. Merlin eventually grows suspicious of her and is eventually imprisoned by Morgan with the very spells he has taught her. She disguises herself as Guinevere and seduces Arthur — this results in her conceiving Mordred who, once grown. assists his mother in her plots against Arthur. Their plans eventually work against them: Morgan is undone by Merlin and is killed by her own son, and Mordred — though he mortally wounds Arthur at the climactic battle, is killed by his dying father.

In the 1998 television film Merlin, Morgan (played by Helena Bohnam Carter) is not only a subversive figure but a disfigured one as well. Like the Morgan of Excalibur, she sees through Uthur's disguise as Gorlois when no one else does, and is later taught magic. But unlike Excalibur's Morgan she is presented not as the predominate villainess but as a pawn in a larger battle between Queen Mab and Merlin. Additionally, this Morgan is afforded some manner of redemption before her death. She eventually comes to question Mab's use of her son Mordred in her plans to undo Arthur. Though Mab kills her, it is clear that Morgan was undergoing a change of heart.

Morgan le Fay also appears in the TV series Stargate. Alternately known as Ganos Lal, she is an "ascended Ancient" (the most advanced of all known races) who inspired the descriptions of the Morgan le Fay of legend. By keeping watch on Myrddin (Merlin, also an ascended being), she ensures that the Sangraal (a stone with great powers) is hidden in an alternate dimension away from both the Ancients and the Ori (their enemies), both of whom might use the Sangraal for destructive purposes. Of interest in this manifestation in Stargate is the intergalactic approach to the Arthurian Legend — in the show, the legends are discovered to have been inspired by actual events that span various galaxies (Arthur and his men, for instance, go in search of the Sangraal on three planets). Morgan herself is of particular interest because of her largely benevolent characterization in this series — one that differs markedly from more common characterizations. Unlike the other, famous intergalactic take on the Arthurian legend seen in Camelot 3000, the Morgan in Stargate is not a villain so much as a figure reminiscent of the Celtic "fae" — formidable creatures with greater powers than humans and different codes of conduct and behavior.

Morgan le Fay also appears in a number of other films: Camelot (1967), Prince Valiant (1997), Arthur the King (1985), Knights of the Round Table (1953),and the TV adaptation of Bradley's Mists of Avalon. Though she often appears as a villain in these films, certain of them endeavor to present her in more nuanced and complex lights.

In addition to her appearances in literature, television, and film, Morgan le Fay is also frequently mentioned in the context of neo-pagan religious groups. She is alternately worshipped as a goddess, hailed as a symbol of feminine power, and adopted as a spiritual name. Susa Morgan Black, a modern druid, claims that Morgan is one of the oldest Celtic goddess and praises Marion Zimmer Bradley for "rescuing" Morgan from patriarchal Christian perceptions. Black claims, based on the fact that names and titles similar to "Morgan" appear across various Celtic literatures, that Morgan is the "third aspect of the Sacred Triple Goddess, the essence of the powerful Crone, Warrioress, and Seductress." In another example, Lady Morgan le Fay, of the Stone Circle Coven, has adopted this name for herself, saying that it "refers not so much to Morgan le Fay as portrayed in the Morte Arthur, but as she is imagined in the telling of the The Mists of Avalon. The challenges that this Morgan le Fay faced in Zimmer Bradley’s version of the Arthurian legend have resonated deeply with me" (quotation from the coven's website, which is no longer online). Many of these groups cite Marion Zimmer Bradley as an influence in their discovery of Morgan le Fay, and seem inspired by Bradley’s attempts to reclaim this character from her consistently negative portrayal in older works.

This survey of references to Morgan le Fay reveals this character’s malleability—she is alternately cast as a healer, villain, enchantress, seductress, or some combination thereof, depending on the needs of the work in question. This versatility has no doubt played a part in the continued cultural relevance that this character has enjoyed across the centuries and continues to hold in contemporary culture as well.

BibliographyAriosto, Ludovico. Orlando Furioso: A New Verse Translation. Trans. David R. Slavitt. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2009.

Benko, Debra A. "Morgan le Fay and King Arthur in Malory's Works and Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Mists of Avalon: Sibling Discord and the Fall of the Round Table." In The Significance of Sibling Relationships in Literature. Ed. Johanna Stephens Mink and Janet Doubler Ward. Bowling Green: Popular, 1992. Pp. 23-31.

Bruce, Christopher W. The Arthurian Name Dictionary. New York: Garland, 1999.

Capps, Sandra Elaine. "Morgan le Fay as Other in English Medieval and Modern Texts." Diss. University of Tennessee, 1996.

Chrétien de Troyes. The Complete Romances of Chrétien de Troyes. Ed. David Staines. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Carolyn, Larrington. King Arthur’s Enchantresses: Morgan and Her Sisters in Arthurian Tradition. London: I. B. Tauris, 2006.

Colahan, Clark. "Morgain the Fay and the Lady of the Lake in a Broader Mythological Context." SELIM 1, 1991. Pp. 83-105.

Crater, Theresa. "The Resurrection of Morgan le Fey: Fallen Woman to Triple Goddess." FEMSPEC 3:1, 2001. Pp. 12-21.

Curtis, Renée L, ed. The Romance of Tristan: The Thirteenth-Century Old French 'Prose Tristan.' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Dixon-Kennedy, Mike. Athurian Myth and Legend: An A-Z of People and Places. London: Blandford, 1995.

Fries, Maureen. "From the Lady to the Tramp: The Decline of Morgan le Fay in Medieval Romance." Arthuriana (4:1) 1994. Pp. 1-18.

Geoffrey of Monmouth. Life of Merlin: Vita Merlini. Trans. Basil Clark. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1973.

Hemmi, Yoko. "Morgain la Fée's Water Connection." Studies in Medieval English Language and Literature 6, 1991. Pp. 19-36.

Herrad, Imogen Rhia. "Vanishing Tricks of a Goddess." New Welsh Review 13:4 (52) 2001. Pp. 14-15.

Lacy, Norris J. The Arthurian Encyclopedia. New York: Garland, 1986

-----, ed. Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation. New York: Garland, 1993-95.

Layamon. Layamon's Arthur: the Arthurian section of Layamon's Brut (lines 9229-14297). Edited and Translated by W. R. J. Barron and S. C. Weinberg. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2001.

Lundy, Anita G. "The Christianization of Morgan le Fay." Postscript 4:2 (22) 1998. Pp. 22-28.

Lupack, Barbara T. The Girl's King Arthur: Tales of the Women of Camelot. Dallas: Scriptorium Press, 2010.

Malory, Thomas. The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. Ed. Eugéne Vinaver. Revised by P.J.C. Field. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990.

McCarthy, Terence. "Did Morgan le Fay Have a Lover?" Medium Aevum 60:2, 1991. Pp. 284-89.

Paton, Lucy Allen and Roger Sherman Loomis. Studies in the Fairy Mythology of Arthurian Romance. New York: B. Franklin, 1960.

Pyle, Howard. North Folk Legends of the Sea. Harper's Magazine, Vol. 104, 1902. Digitized by the Making of American Project, affiliated with Google Books

Saul, MaryLynn Dorothy. A Rebel and a Witch: The Historical Context and Ideological Function of Morgan le Fay in Malory's 'Le Morte Darthur.' Diss. Ohio State University, 1994.

Sklar, Elizabeth S. "Thoroughly Modern Morgan: Morgan le Fey in Twentieth-Century Popular Arthuriana." In Popular Arthurian Traditions. Ed. Sally K Slocum. Bowling Green, OH: Popular, 1992. Pp. 24-35.

Spivack, Charlotte. "Morgan Le Fay: Goddess or Witch?" In Popular Arthurian Traditions. Ed. Sally K. Slocum. Bowling Green, OH: Popular, 1992. Pp. 18-23.

Thompson, Raymond H. "The First and Last Love: Morgan le Fay and Arthur." In Arthurian Women: A Casebook. Thelma S. Fenster, ed. New York: Garland, 1995. Pp. 331-44.

Valdés-Miyares, Rubén. "Morgan's Queendom: The Other Arthurian Myth." In Avalon Revisited. Ed. María José Alvarez-Faedo. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang, 2007. Pp. 133-5.

Winney, James, ed. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. New York: Broadview Press, 1995.

Read Less