Read Less

Dragons and serpents are very closely related in the bestiary tradition. Dragons are described as the largest of serpents; allegorically, they are like the Devil, who is sometimes presented as a monstrous serpent (194). Vipers, the type of snake given the most attention, are similarly described as wicked and cunning and are associated particularly with adultery. (This claim is adapted largely from Ambrose's

Hexameron (195).) The classification of dragons as serpents is particularly interesting given that "dragon" and "serpent" are sometimes used interchangeably in medieval Arthuriana; it is sometimes difficult to know which creature is meant.

Dragons frequently appear in dreams or as part of prophesies. One of the earliest Arthurian narratives, Geoffrey of Monmouth's

History of the Kings of Britain, contains a particularly memorable dragon prophesy. The king Vortigern is attempting to build a castle, but it has fallen several times. When he asks his sages for an explanation, they say that the blood of a fatherless boy will make the castle stand. The kingdom is searched until such a child,

Merlin, is found. However, Merlin demonstrates that the sages have lied and informs Vortigern that the castle he is trying to build will not stand because there is an underground pool beneath it, and under that there are two hollow stones containing sleeping dragons. When the pool is drained and the stones moved, a red dragon and a white dragon emerge and fight until the red dragon is wounded. After it is wounded, the red dragon forces the white dragon back – but Merlin still prophesies that "its death hastens" (131). Merlin explains that the red dragon represents the people of Britain who will be oppressed by the white dragon, but he then explains that the white dragon will be put down in turn by the Boar of Cornwall (that is,

Arthur). This prophesy leads into a lengthy string of prophesies that make frequent use of animal imagery (131). (Though the prophesy of the red and white dragons is the most famous, other animals featured include the Boar of Cornwall (who represents Arthur), the Lion of Justice, the German Worm, the Eagle of the Broken Covenant, the Boar of Commerce, and the Ass of Wickedness (131-42).) A similar story of the two dragons is also told in the Vulgate Cycle's

Merlin, but this version differs notably; here, Merlin tells Vortigern that the red dragon represents Vortigern himself, who has wrongly taken the kingdom from Constant's sons, the rightful heirs, while the white dragon represents the birthright of those two young men, who will reclaim the kingdom (1.185). The Middle English

Prose Merlin repeats the story, following the French Vulgate's rather than Geoffrey of Monmouth's version.

While Geoffrey of Monmouth's

History features physical dragons as the basis of prophesy, dreams of dragons function similarly in other texts. In the

Alliterative Morte Arthure, Arthur dreams of a dragon defeating a bear in battle; some of his philosophers explain that Arthur himself is the dragon, and the bear represents the tyrants that torment Arthur's people or, perhaps, a giant. The dream foretells Arthur's successful fight against the Giant of Mont St. Michel (155-157). A similar dream appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth, the Vulgate

Merlin, and Malory's

Morte d'Arthur, where Arthur dreams of a

bear flying through the air. This bear then battles a dragon and is defeated. The dream is interpreted by Arthur's philosophers as representing Arthur's victory over the giant of Mont St. Michel (Monmouth 182-3; L-G 1.403; Malory 1.196-7). (In Caxton's edition, the animal is a

boar rather than a bear.)

Like their larger family members, serpents also feature in dreams and prophesy. When

Gawain spends the night at the Grail Castle in the Prose

Lancelot, he encounters an enormous multicolored serpent thrashing around an empty room. Gawain watches until the serpent stretches out, and then a hundred serpents swarm out of its mouth. The large serpent leaves the room and encounters a fierce leopard; after a fight, the serpent retreats and goes back to the original chamber, where it and the hundred serpents fight for most of the night until all of them are dead (3.100-101). Gawain encounters a hermit later that day, who tells him that the large serpent represents Arthur, who will leave his country to fight with a knight and then return to fight his kin, represented by the hundred serpents. (The hermit does not identify

Lancelot as the leopard, but surely this is the conflict that is meant (3.102).)

Dragons and serpents often serve an important prophetic function, but physical dragons are more often a menace to be defeated. Many Arthurian knights face down dragons in battle, including perhaps the most famous of Arthur's knights, Lancelot. In the French Prose

Lancelot, Lancelot encounters a tombstone that reads: "this tombstone will not be lifted until the leopard, from whom is to descend the great lion, puts a hand to it, and he will lift it easily, and afterwards the great lion will be begotten in the beautiful daughter of the king of the land beyond" (3.162). When Lancelot lifts the stone, a dragon flies out from under it, and Lancelot fearlessly destroys it. His victory against the dragon then encourages the people to lead Lancelot to King Pelles's daughter in the hope that he will be able to free her from the boiling water in which she is trapped, and this success in turn leads to the conception of

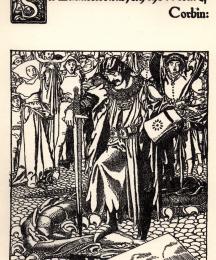

Galahad – the very event the tombstone spoke of (3.163-4). A similar version of this story appears in Malory's

Morte d'Arthur.

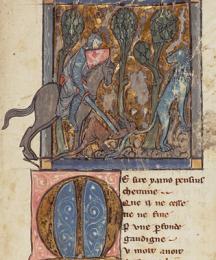

Although there is no explanation of why the dragon is an antagonist in these stories of Lancelot's adventure, other works also suggest that the dragon is unnatural - which is, it seems, explanation enough. In Chretién's

Yvain, the title character encounters a dragon fighting a

lion. (In the original French, this creature is described as a “serpent… trestoz les rains de flame ardant” (l. 3349, l. 3351) – that is, a serpent burning the lion’s hindquarters with flame.)

Yvain assists the lion, which is the "more natural" creature. He successfully slices the serpent in pieces, though he has to remove just a bit of the lion's tail to free it from the serpent's head. Descriptions of dragons as unnatural may draw on the notion of dragons as evil, which was common in bestiaries, saint's lives, and other contemporary literature.

A particularly memorable battle against a dragon occurs in the Dutch

Roman van Walewein. While Walewein (that is, Gawain) rides in search of a chess set he has promised to bring to Arthur, he and his faithful horse Gringolet encounter a nest of four baby dragons. Walewein begins to fight them, and Gringolet joins in the fight when he is attacked by one of the baby dragons. Having defeated all four, Walewein and Gringolet encounter the older dragon, which Walewein defeats using his spear (41-45). This is one of few episodes that features a physical encounter with baby dragons (though dreams sometimes feature "smaller" dragons); as a result, the dragons in this encounter (a mother with baby) read more as animals than as allegorized forces of evil to be overthrown, as is often the case.

Dragons also feature as a foe in many versions of the

Tristan story, both in French and English. Gottfried von Strassburg's version retells Tristan's fight with the dragon at great length; the dragon torments the people of Ireland so that the king (Iseult's father) promises to give his daughter to the knight who kills the dragon. Tristan fights the dragon until it begins to lose heart, and then he kills it and removes its tongue to prove he has done the deed (119-20). Yet noxious fumes from the tongue make him so ill that he nearly dies. While Tristan lies ill, the king's steward claims to have killed the dragon and chops off its head, bringing it with him to the court so he might claim Iseult. Iseult and her mother ride out to see the dragon and to find its true slayer, since they doubt the story and hope to free Iseult from marrying the steward. They find Tristan and restore him to health, and Tristan is able to use the dragon's missing tongue (which he, of course, has) to prove that he, not the steward, killed the dragon (148). The Middle English

Sir Tristrem also recounts this battle with the dragon (196-99). Though the battle with the dragon is not preserved in what remains of Beroul's

Tristran, Tristran and Iseult both allude to it in their discussion under the tree, and

Mark alludes to it again when he tells Iseult he heard the conversation (25). These many appearances of the dragon fight in versions of the Tristran story positions the fight as a central test of knighthood and proof of Tristran's worthiness; certainly, Iseult's doubt that the steward has successfully killed the dragon suggests that only a worthy, strong knight could successfully defeat such a dangerous creature.

While Tristan and many other knights defeat large dragons, serpents almost overcome two of Arthur's best knights in the Prose

Lancelot. When a knight called Caradoc captures Gawain and takes him prisoner, Gawain is kept in a prison full of venomous snakes, which attack him persistently until his legs swell and he becomes lightheaded. Eventually, a lady in the castle gives him a stick to help him defend himself and an ointment to put on his wounds (2.288-89). She also helps destroy the snakes, so that Gawain can remain in his prison in relative comfort (2.290). Lancelot is similarly saved from serpents by a lady later in the same work; when Lancelot is ambushed by a group of knights, they strip him to his underwear and lower him into a deep well full of poisonous snakes. Though Lancelot tries to defend himself, the serpents attack him and nearly kill him. A young lady is able to rescue him by dropping a rope down the well, and she brings him back to her father's castle. However, her father was one of those who lowered Lancelot into the well, and so he tries to kill him; though Lancelot is still very weak, he is able to defeat her father and flee the castle with the young lady (3.186-189).

Perhaps one of the most tragic appearances of a serpent in medieval Arthuriana appears in the

Morte d'Arthur section of Malory. Arthur and

Mordred's opposing forces have stopped fighting in order to discuss a truce. An adder comes out of the heath-bush and stings a knight in the foot, and the knight draws his sword to kill the snake. When knights on both Arthur's and Mordred's forces see a knight with a drawn sword, they suspect treachery and begin fighting. This battle ends with the death of both Arthur and Mordred (3.1235 ll. 20-27).

Though dragons are often presented as formidable foes, they may also represent a feared knight. Perhaps it is the frightening quality of dragons that make them a good representative for Arthur himself. Dragons often appear on Arthur's standard. The dragon that appears on Arthur's standard in the

Merlin seems to be enchanted, as it "threw such great bursts of fire out of its mouth that the air grew red from it, and the dust that had risen also glowed red wherever the dragon had gone" (1.315). It is interesting to consider whether this dragon is meant to signify Arthur as a dangerous enemy or if the enchantment itself might spark fear in those forces opposing Arthur.

Merlin, in contrast, is compared to a serpent rather than a dragon in the Post-Vulgate

Merlin Continuation. In one episode of this work, Merlin must prevent himself from hearing enchanted harps so he can break an enchantment. The narrative compares his stopping up his ears to an asp, "who stops up one of her ears with her tail and presses the other to the ground so she may not hear the conjuring of the enchanter" (4.249). This account of the asp's ability to stop up its ears strongly resembles the bestiary description of the asp, in which it "presses one ear against the ground, covers and stops up the other with its tail, and not hearing those magical notes [of a snake charmer], does not go out" (197). This comparison is somewhat problematic in that it compares Merlin to a wicked creature; however, it may call to mind Merlin's own demonic heritage, which is an important element of his history in the Post-Vulgate cycle.

In Tennyson's "

Merlin and Vivien," from the

Idylls of the King,

Vivien is described as serpentine on multiple occasions. One particularly memorable instant occurs when she grows angry with Merlin, and she is described as "Stiff as a viper frozen; loathsome sight, / How from the rosy lips of life and love, / Flashed the bare grinning skeleton of death! / White was her cheek; sharp breaths of anger puffed / Her fairy nostril out." The sharp breaths of anger through her nose suggest the fire-breathing dragon, rather than simply a serpent. The comparison here clearly portrays Vivien as treacherous and cunning, able to entrap Merlin. The use of the serpent – particularly the viper – as a sign of evil is remarkably consistent with depictions of serpents in medieval Arthurian texts.

The dragons and serpents of medieval Arthuriana are nearly as varied as they are frequent; they are representatives both of the noble king and of evil to be destroyed. References to these creatures also provide a particularly interesting example of how medieval Arthurian texts are interlinked. The notable similarities and differences between these retellings across texts of different times and languages demonstrate how Arthurian texts inform each other and create a larger tradition.

BibliographyFor more information about the version of works cited, see the Critical Bibliography for this project.

Read Less