Read Less

Robin Hood, Robin Hood

Riding through the glen.

Robin Hood, Robin Hood

With his band of men.

Feared by the bad, loved by the good.

Robin Hood, Robin Hood, Robin Hood

—The Adventures of Robin Hood (ITV series, 1955-60).

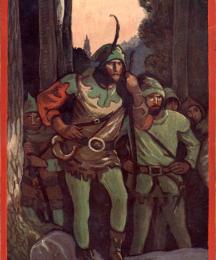

Speak the name Robin Hood and immediately an audience will conjure images of the green-clad archer of Sherwood Forest, or the noble robber who steals from the rich to give to the poor, or the humble leader of the Merry Men, or the one man who will stand up to injustice and tyranny in the Middle Ages. These images of Robin Hood are common, even universal, yet they are not the result of a single, unified tradition—rather, they are the product of a metatextual tradition, one which surpasses and overrides every individual representation of the character. The character of Robin Hood is thus remarkably elusive, despite—or perhaps due to—centuries of intense cultural investment in the legend's stability.

Robin Hood consequently enjoys a double life that few other traditional figures can match, because in every new retelling of the story there are always two Robin Hoods present: the Robin Hood of popular culture, which is an amalgamation of prior representations and cultural forces, and the Robin Hood of the specific story, which is designed to meet the specific needs of the author and the projected audience. The Robin Hood of popular culture is the character that audiences expect and demand, and this character is simultaneously deeply desired and deeply rejected. Audiences want new, up-to-date, and relevant Robin Hoods, Robin Hoods who address the pressing social concerns of the audience and, paradoxically, Robin Hoods who do all these things while satisfying all the elements of the popular tradition. However, unlike the English and American Arthurian tradition with its origins in Malory, the popular-culture Robin Hood is not based in a single text, nor can it be traced back to a major source. Balance between the popular-culture Robin Hood and the Robin Hood of the specific story is rarely achieved—a condition largely attributable to the proscriptions (of behaviors, scenarios, locations, etc.) which bind the traditional Robin Hood. New elements, demanded by audiences to make the traditional story relevant, often collide with concurrent audience expectations of the tradition and are therefore rejected, tradition winning out over innovation.

Robin Hood consequently enjoys a double life that few other traditional figures can match, because in every new retelling of the story there are always two Robin Hoods present: the Robin Hood of popular culture, which is an amalgamation of prior representations and cultural forces, and the Robin Hood of the specific story, which is designed to meet the specific needs of the author and the projected audience. The Robin Hood of popular culture is the character that audiences expect and demand, and this character is simultaneously deeply desired and deeply rejected. Audiences want new, up-to-date, and relevant Robin Hoods, Robin Hoods who address the pressing social concerns of the audience and, paradoxically, Robin Hoods who do all these things while satisfying all the elements of the popular tradition. However, unlike the English and American Arthurian tradition with its origins in Malory, the popular-culture Robin Hood is not based in a single text, nor can it be traced back to a major source. Balance between the popular-culture Robin Hood and the Robin Hood of the specific story is rarely achieved—a condition largely attributable to the proscriptions (of behaviors, scenarios, locations, etc.) which bind the traditional Robin Hood. New elements, demanded by audiences to make the traditional story relevant, often collide with concurrent audience expectations of the tradition and are therefore rejected, tradition winning out over innovation.

However, even the tradition lacks unity. Robin Hood's name, for example, has traditionally included variations such as Robyn Hode (A Gest of Robyn Hode), Robert Hood (favored by the chroniclers), and even Robert, Earl of Huntingdon (Munday's plays of 1598 and 1599). More names entered the tradition, including Robin of Locksley (Sloane MS "Life of Robin Hood"), as the character's popularity increased. The variety of names within the literary texts alone is indicative of a vigorous textual tradition, one which continually adapts to the needs of its many audiences. Scholars of the Robin Hood materials have for centuries been interested in the connections between the literary tradition and the reoccurrence of personal names, like Robin Hood, amongst historically confirmed individuals. Several historians have sought to connect these individuals to the legend's materials but have been unable to reconcile the multiple recurrences of the name "Robin Hood" with a single historically confirmed figure. The antiquarian Joseph Hunter (1783-1861) located a valet de chamber for Edward II named Robyn Hode, one who left the service of the king in 1324 in York—a situation whose scanty historical details closely match the action of one of the earliest surviving Robin Hood stories, A Gest of Robyn Hode (Knight 1994, 23). The Gest is believed to have come into existence sometime in the second half of the fifteenth century, which makes Hunter's candidate an appealing prospect for scholars eager to connect a historical figure to the first Robin Hood reference in high literature, the "rhymes of Robin Hood" mentioned in the Piers Plowman B-text. However, as Stephen Knight has noted, this "ideal candidate" appeared over a century after references to a Hobbehod in Yorkshire (1228-32); a William Robehod (formerly William, son of Robert le Fevere, of Enborne) in Berkshire (1262); and a Gilbert Robynhod in Sussex (1296). If Hunter's valet de chambre, released in 1324 due to an inability to work (Knight 1994, 23), was the origin of the Robin Hood materials, then why, Knight asks, would Robinhood appear as a surname generations prior? Furthermore, Knight notes, there are other individuals contemporary to Hunter's Robyn Hode: a woman, Katherine Robynhod, in London (1325); two different men called Robert Robynhod in different parts of Sussex (1332 and 1381); and John Ball's reference to Hobbe the Robbere (1381). The case for a historical Robin Hood simply cannot be supported.

Though searching for a "real Robin Hood" is not a productive line of inquiry, the literary record places the fictional character in several historical contexts—again contributing to the tradition's discordance. Thus, though Robin Hood has been and continues to be associated with the forests of northern England, there is no medieval or early modern basis for exclusively identifying a single forest with the tradition. For example, Sherwood Forest, which contemporary audiences consider central to the tradition, is named in only one of the four earliest surviving Robin Hood ballads, Robin Hood and the Monk (c. 1450), and in a collection of grammar texts, Lincoln Cathedral MS 132 (first quarter of the fifteenth century). The first line of a scribbled pair of rhymed couplets, "Robyn hod in scherewod stod" (Ohlgren 18), reflects the apparent interchangeability of place names in the tradition: "Robin Hode in Barnsdale stode" is recorded in 1429 as a legal formula indicating an obvious fact (Knight 1994, 263-64). Barnsdale Forest, however, is named in two of the earliest ballads, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (late fifteenth century origins) and A Gest of Robyn Hode (second half of the fifteenth century). In the chronicle tradition, too, Barnsdale is the location of Robin's activities: Walter Bower's continuation of John of Fordun's Scotichronicon (c. 1440s) locates the outlaw exclusively in Barnsdale, and Andrew of Wynton's Orygynal Chronicle of Scotland (c. 1420) places Robin in both Barnsdale and Inglewood. Some texts in the tradition do not name Robin's woodlands at all: neither the early ballad "Robin Hood and the Potter" (c. 1500) nor the chronicler John Major gives a specific name to Robin Hood's forest setting.

The traditional location of the outlaw is thus demonstrably divided in the early written record; the references to Barnsdale and Sherwood, respectively, appear at the same time, though not within the same stories. A slight pattern to the trend is visible: before 1500, Barnsdale is far more commonly named; by the seventeenth century, Sherwood appears to have gained prominence. Further contributing to the chaotic nature of the medieval tradition is a tendency not to affiliate the outlaw with a forest, named or otherwise, as in the first literary reference in Passus V of the B-text of Piers Plowman (c. 1377; B.V.402), Gower's use of the names Robin and Marian in the Mirour de l'Homme (1376-79; 8659-60), and even an oblique reference in Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1380; II.861).

The traditional location of the outlaw is thus demonstrably divided in the early written record; the references to Barnsdale and Sherwood, respectively, appear at the same time, though not within the same stories. A slight pattern to the trend is visible: before 1500, Barnsdale is far more commonly named; by the seventeenth century, Sherwood appears to have gained prominence. Further contributing to the chaotic nature of the medieval tradition is a tendency not to affiliate the outlaw with a forest, named or otherwise, as in the first literary reference in Passus V of the B-text of Piers Plowman (c. 1377; B.V.402), Gower's use of the names Robin and Marian in the Mirour de l'Homme (1376-79; 8659-60), and even an oblique reference in Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1380; II.861).

Another significant element of Robin's character is his nobility of purpose: for example, the Robin Hood of popular culture robs from the rich to give to the poor. However, like the split in locating the tradition in Barnsdale and Sherwood, none of the surviving medieval texts directly reference stealing from the rich to give to the poor. Only the Gest can be said to remotely touch on this theme, for two reasons: first, Robin lays out a code of conduct for his men (l. 49-60); and second, Robin lends money to the unfortunate knight Sir Richard (l. 245-68). The code never directs the outlaws to distribute the wealth they acquire by robbing bishops and archbishops; and Robin emphasizes repeatedly that the money he gives to the knight is a loan, and he expects repayment. Further, the knight is only temporarily poor, and is also of good lineage, noble character, and a good credit risk. Though Robin and his men accumulate the wealth by robbery, they have no underlying social agenda; their charity is accidental and they rob the rich primarily to benefit themselves.

The surviving literary record, however, is contradicted by the Scottish chronicle tradition. Andrew of Wyntoun notes that "Litil Iohun and Robert Hude / Waythmen war commendit gud" (Little John and Robert Hood / Were forest outlaws praised well), and Knight has noted that the inclusion of the word "gud" may only be because it rhymes with "Hude" (Knight 1994, 33). Bower calls Robin Hood a well-known cut-throat, whom "the foolish people are so inordinately fond of celebrating in tragedy and comedy" (Knight 1994, 35); this indicates popularity, though not the cause. However, Major mentions "those most famous robbers Robert Hood, an Englishman, and Little John, who lay in wait in the woods but spoiled of their goods those only that were wealthy [.…] He would allow no woman to suffer injustice, nor would he spoil the poor, but rather enriched them from plunder taken from abbots" (Knight 1994, 37). Major's entry is the closest the medieval tradition, whether literary or chronicle, comes to the concept of specifically robbing the rich with the intention of redistributing the wealth amongst the poor.

However, Knight identifies a strong candidate to integrate the extant literary and chronicle traditions of wealth redistribution. The story exists in at least two versions, in Child 148 and the Forrester's Manuscript—the latter judged by Knight and Ohlgren to appear "most unlikely to have been generated editorially from the broadside version," and thus the basis for their own edition (581). In 1631, the ballad was entered in the Stationer's Register as Robin Hood's Great Prize, though it was later called The Noble Fisherman, or, Robin Hood's Preferment, perhaps because of confusion with Robin Hood's Golden Prize, and Knight and Ohlgren have renamed it Robin Hood's Fishing (581). Whatever the name, Knight's assessment is that, "[f]ar from being an eccentric and trivial ballad, [the story] brings into focus a crucial element of the whole tradition of Robin Hood, the role of charity and the notion of the importance of taking from the rich to give to the poor" (Knight 1994, 69).

Defining the early Robin Hood is thus very difficult, and any consideration of the tradition must take into account the diverse nature of the legend's origins. The medieval and early modern ballads—exact dates of composition are unknown, though critics agree that the character was well known by the fourteenth century, and very likely the thirteenth and perhaps even the twelfth centuries as well—present a character radically different from the hero of the later ballad tradition. Additionally, nineteenth-century and Victorian treatments of the character have continued to influence contemporary authors who retell the tales of Robin Hood; and the demands and requirements of twenty-first-century audiences have likewise altered the character, in cinematic and literary treatments alike. What follows is a brief analysis of Robin Hood's characteristics during three major periods of the legend's development: the medieval / early modern ballads (EARLY), the stepping stone texts of the late sixteenth through nineteenth centuries (MIDDLE), and the advent of film and novels in twentieth and twenty-first centuries (MODERN).

EARLY

Though "character" is a term generally associated with more specificity and interiority than many medieval texts provide, the ballads paint with a broad brush, even by medieval literary standards. Thus, the patterns of Robin's character are inconsistent from ballad to ballad, and even within a single text Robin leaps from arrogant selfishness to stunning selflessness. Given these conditions, however, some generalizations are possible. Robin Hood appears as a man of violent temperament, mercurial in his moods and attitudes, and derisive to the loyal John. Though he frequently abuses his friends and allies at the beginning of a tale, he always makes up for his actions by the story's end, either through physical action (rescuing John in Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne), direct apology (Robin Hood and the Monk), or even monetary compensation (Robin Hood and the Potter). Robin is always devotedly attached to the Blessed Virgin Mary yet firmly opposed to Church hierarchies and authorities, a near-contradiction that enables Stephen Knight to conclude that one of the few certainties of the Robin Hood myth, whether medieval or modern, is that the outlaw "represents principled resistance to wrongful authority—of many different kinds and in many periods and contexts" (Knight 2003, xi) .

Modern audiences, expecting a merry outlaw clad in green gamboling through the summer forest, are often shocked by ballads like Robin Hood and the Monk. The Robin Hood of this ballad is an unloveable figure, one whose religious devotion is matched by puerile whining and brash actions. John is far more heroic and central to the poem than Robin; the majority of the action centers around John's efforts to free Robin from the Sheriff's prison. Even John, however, is not without flaws that present contemporary audiences with a serious moral dilemma: John and Much murder a monk and his young page as part of their campaign to free Robin, steal their victims' identities, deceive the King, and lie and fight their way into the Sheriff's stronghold to eventually free Robin. The actions of John and Much reflect their leader's own attitudes, a codependency which Robin acknowledges by offering John leadership of the outlaw band.

Modern audiences, expecting a merry outlaw clad in green gamboling through the summer forest, are often shocked by ballads like Robin Hood and the Monk. The Robin Hood of this ballad is an unloveable figure, one whose religious devotion is matched by puerile whining and brash actions. John is far more heroic and central to the poem than Robin; the majority of the action centers around John's efforts to free Robin from the Sheriff's prison. Even John, however, is not without flaws that present contemporary audiences with a serious moral dilemma: John and Much murder a monk and his young page as part of their campaign to free Robin, steal their victims' identities, deceive the King, and lie and fight their way into the Sheriff's stronghold to eventually free Robin. The actions of John and Much reflect their leader's own attitudes, a codependency which Robin acknowledges by offering John leadership of the outlaw band.

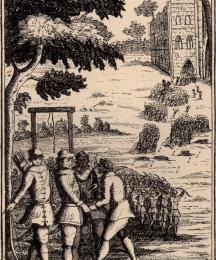

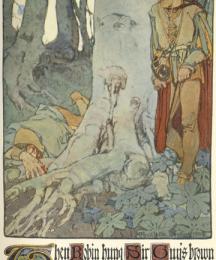

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, however, is by far the most disturbing of the early ballads. After Robin has a dream vision, he and John encounter the strange figure of Sir Guy, a man clad in a whole horsehide (29-30). Robin and John separate; Robin engages Guy in a long and bloody swordfight, which ends when he beheads his opponent, and disfigures and verbally abuses the corpse; John attempts to rescue fellow outlaws from the Sheriff's men but is captured and nearly executed. Only Robin's timely appearance, disguised as Guy, saves John. The ballad is particularly unsettling in its graphic, uncompromising depiction of Robin's savage treatment of his opponent—both in life and after death—which, combined with the narrative skips which the ballad genre frequently demands, results in a story that is rarely retold in its entirety.

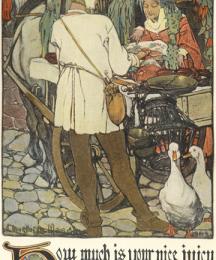

The two other early ballads, Robin Hood and the Potter and A Gest of Robyn Hode, depict versions of Robin that are very different from his characterization in Monk and Gisborne. Robin is more a slyly engaging trickster and greenwood brawler in Potter than the violent and abrasive brigand of Monk and Gisborne; in A Gest, Robin is less involved in the story action and more of an authority figure. Readers familiar with the Arthurian tradition will recognize in A Gest the echoes of Arthur's position as director of adventures, but not adventurer himself, in Robin's detached centrality to the story's plot. Robin's social status is more ambiguous in A Gest than in any of the other early ballads; his behavior is also more noble and courtly, and it is in this story—but no other medieval version—that the theme of wealth redistribution begins to develop. Thus, the Robin of A Gest is the medieval variation that resonates best with modern audiences and their expectations of the legend.

MIDDLE

Between the medieval / early modern ballads and the multiple media which characterize the modern or contemporary Robin Hood lies several hundred years of accretion. Several works have had a substantial impact, either upon the character's evolution or upon critical perceptions of the legend. These works serve as stepping stones in the legend's development, building upon their predecessors to slowly construct the framework for what has become the recognizable, and modern, Robin Hood.

Anthony Munday's pair of Robin Hood plays, The Downfall of Robert Earle of Huntington (1598) and The Death of Robert Earle of Huntington (1599), are a critical turning point in the literary Robin Hood's personal story: Munday was the first to produce texts in which Robin / Robert is a dispossessed Earl, loyal to good king Richard, a concept which has remained central to the legend ever since. However, Knight notes that, despite Munday's raising of Robin into the ranks of the nobility, it is not until Martin Parker's seventeenth century A True Tale of Robin Hood that Robin becomes an individual; this development of the figure into what can begin to be called a true "character" is dependent upon Munday's ennoblement, which ties the figure and the legend to a specific time and place. Robin Hood becomes a unique individual when he is contextualized and historicized; as a free-floating fictional ballad hero, he lacks the foundations for personality that a pseudo-historical figure possesses a priori. Knight notes, however, that the development of Robin Hood's biography is not confined to the page alone (Knight 1994, 23). Indeed, the conjunction of lively popular tradition and literary effort is likely the impulse behind the development of Robin Hood from figure to character.

Though the popular tradition of Robin Hood was easily sustained from the sixteenth into the eighteenth centuries, the literary footprint for those periods remains small. A large corpus of later ballads has survived—some in multiple copies—and Knight and Ohlgren note that these texts have little to do with the medieval / early modern ballads: format, length, theme, and focus have all shifted (Knight and Ohlgren 453). These ballads, moreover, contribute little to the development of Robin Hood as a character, though the compilation of multiple later ballads into chapbooks or collections may contribute to a perceived unification of the tradition. Certain compilations, such as the famed Percy Folio, are important evidence toward the widespread availability of multiple tales of Robin Hood—though the Percy Folio was not published until 1867, its mere existence in the mid-seventeenth century indicates the availability of the tales, both individually and collectively. These compilations are significant milestones in the process of the canonization of the Robin Hood character, and with canonization came increasingly sophisticated refinements of character, particularly in the nineteenth century, at the hands of authors and poets ranging from Sir Walter Scott to John Keats, J. R. Reynolds, and others.

Knight attributes the nineteenth-century renewal of interest in the Robin Hood tradition to the work of the antiquarian Joseph Ritson, whose 1795 publication of Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw not only arrived in the midst of the French Revolution, but was accompanied by an introduction espousing Ritson's own radical politics. The yeoman with a complexion "brown as a hazel nut" of Scott's Ivanhoe (chapter 7), solidly dependable on the battlefield while his social betters succumb to flights of tactically-unsound chivalry, has been read as a product of Ritson's thrusting of the tradition into the rapidly changing social fabric. The deep-seated nostalgia movement, in which Scott's novels are located, looked to Robin Hood as a man and as a myth of a bygone era of strong values, security, and social calm. Keats' poem "Robin Hood," a response to his friend Reynolds' romantic greenwood fantasy, further complicated the trend; both Scott and Keats moved the character into deeper examinations of social boundaries and interpersonal relationships than the ballad tradition had permitted. Robin Hood was becoming a national fiction, like King Arthur, and thus, like Arthur, developed a canonized personality, complete with biographical details.

Knight attributes the nineteenth-century renewal of interest in the Robin Hood tradition to the work of the antiquarian Joseph Ritson, whose 1795 publication of Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw not only arrived in the midst of the French Revolution, but was accompanied by an introduction espousing Ritson's own radical politics. The yeoman with a complexion "brown as a hazel nut" of Scott's Ivanhoe (chapter 7), solidly dependable on the battlefield while his social betters succumb to flights of tactically-unsound chivalry, has been read as a product of Ritson's thrusting of the tradition into the rapidly changing social fabric. The deep-seated nostalgia movement, in which Scott's novels are located, looked to Robin Hood as a man and as a myth of a bygone era of strong values, security, and social calm. Keats' poem "Robin Hood," a response to his friend Reynolds' romantic greenwood fantasy, further complicated the trend; both Scott and Keats moved the character into deeper examinations of social boundaries and interpersonal relationships than the ballad tradition had permitted. Robin Hood was becoming a national fiction, like King Arthur, and thus, like Arthur, developed a canonized personality, complete with biographical details.

Howard Pyle's 1883 book The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire and Reginald De Koven's 1890 light opera Robin Hood opened the floodgates, and established Robin Hood as an English, and American, national hero. Both works were widely available in England and America, to say nothing of other English-speaking countries; and the figure of Robin—stout, bearded, wearing tights, tunic, and feathered cap, laughing his way through adventures—finally began to coalesce. However, as the widespread visual representations of Robin Hood unified the character, development ossified. The demand for psychological depth—or at least, more depth than previously displayed—emerged, undoubtedly in response to the growing influence of the novel. Robin Hood's status as a figure of folklore and low culture, however, restrained the character; because so many people had become familiar with the character at such an early age, firmly establishing in their minds an extensive list of traits and requirements that Robin Hood needed to meet to be considered properly "Robin Hood," yet simultaneously always eager for more tales and stories, character development was inevitably handicapped.

MODERN

The commercially viable Robin Hood—restrained by tradition to Sherwood Forest during the middle of the Angevin era of the Plantaganet dynasty, armed with longbow and broadsword, devoted to Maid Marian, generally of the gentry if not of the nobility, and a laughing, roguish leader of a band of noble robbers—was the Robin Hood that the early twentieth century inherited, and propagated through film. Robin Hood was the subject of some of the earliest cinematic experiments, likely because the well-known story, repetitive structures, and clear visual elements appealed to filmmakers and audiences alike. Knight notes that the "potency of the Robin Hood story in the cinema is revealed by a simple but dramatic statistic: five Robin Hood films were made before 1914" (1994, 218). Robin Hood, embodied by an actor, was not new to the dramatic tradition; rather, the novelty was in the availability of a single, consolidated image. Earlier plays, play-games, and dramas were traditionally very local, or (as in the case of the travelling De Koven musical Robin Hood and its 1901 sequel Maid Marian) limited by commercial concerns for theatrical productions.

The theatrical attraction to the iconographic Robin Hood of the late nineteenth century did not encourage further character development. Though each actor who has played Robin Hood has left an indelible mark on the character and influenced his successors profoundly—for example, Errol Flynn's laughing swashbuckler draws deeply from Pyle's drawings and Douglas Fairbanks' posing; likewise Kevin Costner's prince of thieves draws as much on Flynn as on Richard Greene—the variations are always minor. Stephen Knight notes that,

The theatrical attraction to the iconographic Robin Hood of the late nineteenth century did not encourage further character development. Though each actor who has played Robin Hood has left an indelible mark on the character and influenced his successors profoundly—for example, Errol Flynn's laughing swashbuckler draws deeply from Pyle's drawings and Douglas Fairbanks' posing; likewise Kevin Costner's prince of thieves draws as much on Flynn as on Richard Greene—the variations are always minor. Stephen Knight notes that,

Actors love playing Robin Hood not only because they can wear green tights and do the Basil Rathbone swordfight, but because there are almost no lines to learn. A tradition of this centrally dramatic and active nature does not respond well to the modes of the lyric poem and the novel, respondent as those forms are to internalized depth and nuanced representation of feeling. The techniques and attitudes of 'high culture' writing seem hostile to the essence of a flexible, popular, immediate and dramatic tradition. (Knight 1994, 3)

In the face of such investment in tradition and the rejection of "nuanced representation of feeling," the evolution of the character in the mid to late twentieth century depended largely on the needs of the audiences consuming the films, television programs, novels, comic books, and assorted other media in which Robin Hood appeared. Likewise, Robin Hood was given more depth, not through his own merits or development, but by the investment in deepening the characters who surround him: Little John, the Sheriff, the Merry Men, Marian, and Tuck, to name only a few, all grew significantly, in part because Robin himself could not. The development of these figures into characters—a process begun by Munday in his plays nearly four centuries earlier—allowed Robin to retain his static characteristics while still engaging his audience.

Creative character experimentation appears to have been largely relegated to the written page. Robin Hood's literary appearances respond to more than market forces alone, reflecting both a broad collection of political, cultural, and societal concerns and an eagerness to share a personal retelling of a well-known story. However, the former dominance of the written Robin Hood has been overturned by his cinematic twin. Thus, modern Robin Hood novels may temporarily become best sellers, or enjoy modest financial success, but the influence of these books upon the filmed versions of the legend appears to be minimal; the influence of cinema upon the literary is much greater. The range of literary characters sharing the name Robin Hood is impressive: Robin has been a former Crusader suffering post-traumatic stress disorder (Jennifer Roberson's Lady of the Forest and sequel Lady of Sherwood), a neurotic planner with better administrative skills than archery talent (Robin McKinley's The Outlaws of Sherwood), a fiercely honorable landholder turned lawyer (Parke Godwin's Sherwood and its sequel Robin and the King), and a fop forced into responsibility (Stephen Lawhead's Hood), to name only a few. Additionally, Robin Hood, or characters so clearly patterned after him that differentiating them from Robin does both a disservice, repeatedly appears in any number of modern romance novels, comic books, and other culturally significant but critically overlooked written forms of popular culture.

Nearly seven centuries after his first appearance in literature, Robin Hood continues to significantly influence high and low culture, and is less a character than a wide-ranging cultural force. The following is a fragmentary list of works significant in the development of the Robin Hood character; this list is intended to provide a representative range of material rather than an exhaustive bibliography. For a fuller bibliography, see the Bibliography pages of The Robin Hood Project.

Bibliography

Early

Robin Hood and the Monk (late fifteenth century).

Robin Hood and the Potter (c. 1500).

A Gest of Robyn Hode (early sixteenth century).

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (early sixteenth century).

Andrew of Wyntoun, Orygynale Chronicle (c. 1420).

John of Fordun, Walter Bower, Scotichronicon (c. 1440).

John Mair, Historia Majoris Britanniae (1521).

John Bellenden, Chronicles of Scotland (manuscript 1533; printed 1540).

Middle

Anthoy Munday, The Downfall of Robert Earle of Huntington (1598), The Death of Robert Earle of Huntington (1599).

Robin Hood's Progress to Nottingham (1600-1656).

Martin Parker, A True Tale of Robin Hood (1632).

Robin Hood and Maid Marian (post 1660).

Robin Hood and His Crew of Souldiers (1661).

Sir Walter Scott, Ivanhoe (1818), chapter 41.

J. R. Reynolds, "Sonnet on Robin Hood I," "Sonnet on Robin Hood II" (1819).

John Keats, "Robin Hood, to a Friend" (1820).

Pierce Egan, Robin Hood and Little John: Or, The Merry Men of Sherwood Forest (1840).

Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire (1883).

Modern

Reginald De Kovan, Robin Hood (1890), Maid Marian (1901).

Robin Hood (1922). Dir. Allan Dwan. Perfs. Douglas Fairbanks (Robin Hood), Enid Bennett (Marian).

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Dir. Michael Curtiz and William Keighley. Perfs. Errol Flynn (Robin Hood), Olivia de Havilland (Marian).

The Adventures of Robin Hood. Perf. Richard Greene (Robin Hood). ITV / Sapphire Films (1955-1958).

Robin of Sherwood. Perf. Michael Praed (Robin Hood-Loxley), Jason Connery (Robin Hood-Huntingdon), Judi Trott (Marion). HTV (1984-86).

Robin McKinley, The Outlaws of Sherwood (1989).

Robin Hood (1991). Dir. John Irvin. Perfs. Patrick Bergin (Robin Hood).

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. Dir. Kevin Reynolds. Perf. Kevin Costner (1991).

Parke Godwin, Sherwood (1991), Robin and the King (1994.)

Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993). Dir. Mel Brooks. Perfs. Cary Elwes (Robin Hood).

Jennifer Roberson, Lady of the Forest (1993), Lady of Sherwood (1999).

Elsa Watson, Maid Marian: A Novel (2004).

Robin Hood. Perf. Jonas Armstrong (Robin Hood), Lucy Griffiths (Marian). BBC (2006-07).

Works Cited

Knight, Stephen.

Robin Hood: A Complete Study of the English Outlaw. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994.

---.

Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003.

Knight, Stephen and Thomas Ohlgren, eds.

Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

Ohlgren, Thomas H.

Robin Hood: The Early Poems, 1465-1560: Texts, Contexts, and Ideology. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2007.

Read Less

Robin Hood consequently enjoys a double life that few other traditional figures can match, because in every new retelling of the story there are always two Robin Hoods present: the Robin Hood of popular culture, which is an amalgamation of prior representations and cultural forces, and the Robin Hood of the specific story, which is designed to meet the specific needs of the author and the projected audience. The Robin Hood of popular culture is the character that audiences expect and demand, and this character is simultaneously deeply desired and deeply rejected. Audiences want new, up-to-date, and relevant Robin Hoods, Robin Hoods who address the

Robin Hood consequently enjoys a double life that few other traditional figures can match, because in every new retelling of the story there are always two Robin Hoods present: the Robin Hood of popular culture, which is an amalgamation of prior representations and cultural forces, and the Robin Hood of the specific story, which is designed to meet the specific needs of the author and the projected audience. The Robin Hood of popular culture is the character that audiences expect and demand, and this character is simultaneously deeply desired and deeply rejected. Audiences want new, up-to-date, and relevant Robin Hoods, Robin Hoods who address the

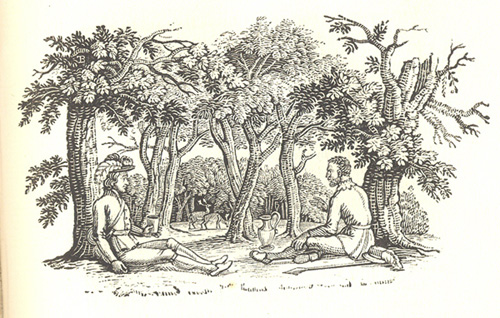

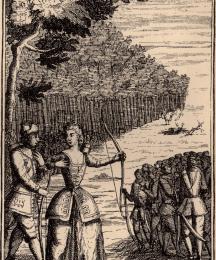

![Original [Wood]Cut of the Ballad](https://d.lib.rochester.edu/sites/default/files/styles/creatorpage/public/v2p180.jpg?itok=tfik7vRv)

The traditional location of the outlaw is thus demonstrably divided in the early written record; the references to Barnsdale and Sherwood, respectively, appear at the same time, though not within the same stories. A slight pattern to the trend is visible: before 1500, Barnsdale is far more commonly named; by the seventeenth century, Sherwood appears to have gained prominence. Further contributing to the chaotic nature of the medieval tradition is a tendency not to affiliate the outlaw with a forest, named or otherwise, as in the first literary reference in Passus V of the B-text of Piers Plowman (c. 1377; B.V.402), Gower's use of the names Robin and Marian in the Mirour de l'Homme (1376-79; 8659-60), and even an oblique reference in Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1380; II.861).

The traditional location of the outlaw is thus demonstrably divided in the early written record; the references to Barnsdale and Sherwood, respectively, appear at the same time, though not within the same stories. A slight pattern to the trend is visible: before 1500, Barnsdale is far more commonly named; by the seventeenth century, Sherwood appears to have gained prominence. Further contributing to the chaotic nature of the medieval tradition is a tendency not to affiliate the outlaw with a forest, named or otherwise, as in the first literary reference in Passus V of the B-text of Piers Plowman (c. 1377; B.V.402), Gower's use of the names Robin and Marian in the Mirour de l'Homme (1376-79; 8659-60), and even an oblique reference in Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1380; II.861). Modern audiences, expecting a merry outlaw clad in green gamboling through the summer forest, are often shocked by ballads like Robin Hood and the Monk. The Robin Hood of this ballad is an unloveable figure, one whose religious devotion is matched by puerile whining and brash actions. John is far more heroic and central to the poem than Robin; the majority of the action centers around John's efforts to free Robin from the Sheriff's prison. Even John, however, is not without flaws that present contemporary audiences with a serious moral dilemma: John and Much murder a monk and his young page as part of their campaign to free Robin, steal their victims' identities, deceive the King, and lie and fight their way into the Sheriff's stronghold to eventually free Robin. The actions of John and Much reflect their leader's own attitudes, a codependency which Robin acknowledges by offering John leadership of the outlaw band.

Modern audiences, expecting a merry outlaw clad in green gamboling through the summer forest, are often shocked by ballads like Robin Hood and the Monk. The Robin Hood of this ballad is an unloveable figure, one whose religious devotion is matched by puerile whining and brash actions. John is far more heroic and central to the poem than Robin; the majority of the action centers around John's efforts to free Robin from the Sheriff's prison. Even John, however, is not without flaws that present contemporary audiences with a serious moral dilemma: John and Much murder a monk and his young page as part of their campaign to free Robin, steal their victims' identities, deceive the King, and lie and fight their way into the Sheriff's stronghold to eventually free Robin. The actions of John and Much reflect their leader's own attitudes, a codependency which Robin acknowledges by offering John leadership of the outlaw band. Knight attributes the nineteenth-century renewal of interest in the Robin Hood tradition to the work of the antiquarian Joseph Ritson, whose 1795 publication of Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw not only arrived in the midst of the French Revolution, but was accompanied by an introduction espousing Ritson's own radical politics. The yeoman with a complexion "brown as a hazel nut" of Scott's Ivanhoe (chapter 7), solidly dependable on the battlefield while his social betters succumb to flights of tactically-unsound chivalry, has been read as a product of Ritson's thrusting of the tradition into the rapidly changing social fabric. The deep-seated nostalgia movement, in which Scott's novels are located, looked to Robin Hood as a man and as a myth of a bygone era of strong values, security, and social calm. Keats' poem "Robin Hood," a response to his friend Reynolds' romantic greenwood fantasy, further complicated the trend; both Scott and Keats moved the character into deeper examinations of social boundaries and interpersonal relationships than the ballad tradition had permitted. Robin Hood was becoming a national fiction, like King Arthur, and thus, like Arthur, developed a canonized personality, complete with biographical details.

Knight attributes the nineteenth-century renewal of interest in the Robin Hood tradition to the work of the antiquarian Joseph Ritson, whose 1795 publication of Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw not only arrived in the midst of the French Revolution, but was accompanied by an introduction espousing Ritson's own radical politics. The yeoman with a complexion "brown as a hazel nut" of Scott's Ivanhoe (chapter 7), solidly dependable on the battlefield while his social betters succumb to flights of tactically-unsound chivalry, has been read as a product of Ritson's thrusting of the tradition into the rapidly changing social fabric. The deep-seated nostalgia movement, in which Scott's novels are located, looked to Robin Hood as a man and as a myth of a bygone era of strong values, security, and social calm. Keats' poem "Robin Hood," a response to his friend Reynolds' romantic greenwood fantasy, further complicated the trend; both Scott and Keats moved the character into deeper examinations of social boundaries and interpersonal relationships than the ballad tradition had permitted. Robin Hood was becoming a national fiction, like King Arthur, and thus, like Arthur, developed a canonized personality, complete with biographical details. The theatrical attraction to the iconographic Robin Hood of the late nineteenth century did not encourage further character development. Though each actor who has played Robin Hood has left an indelible mark on the character and influenced his successors profoundly—for example, Errol Flynn's laughing swashbuckler draws deeply from Pyle's drawings and Douglas Fairbanks' posing; likewise Kevin Costner's prince of thieves draws as much on Flynn as on Richard Greene—the variations are always minor. Stephen Knight notes that,

The theatrical attraction to the iconographic Robin Hood of the late nineteenth century did not encourage further character development. Though each actor who has played Robin Hood has left an indelible mark on the character and influenced his successors profoundly—for example, Errol Flynn's laughing swashbuckler draws deeply from Pyle's drawings and Douglas Fairbanks' posing; likewise Kevin Costner's prince of thieves draws as much on Flynn as on Richard Greene—the variations are always minor. Stephen Knight notes that,