We will continue to publish all new editions in print and online, but our new online editions will include TEI/XML markup and other features. Over the next two years, we will be working on updating our legacy volumes to conform to our new standards.

Our current site will be available for use until mid-December 2024. After that point, users will be redirected to the new site. We encourage you to update bookmarks and syllabuses over the next few months. If you have questions or concerns, please don't hesitate to contact us at robbins@ur.rochester.edu.

Appendix 2: Music

APPENDIX 2: MUSIC: FOOTNOTES

1 Richard Rastall notes that since some of the costuming directions in the text (notably Anima’s black-on-white dress) may indicate a Dominican connection, it is possible that the music for these chants would have been drawn from Dominican, rather than Sarum, sources (Minstrels Playing, p. 459). See also pp. 451–64 for a thorough discussion of the music in the play.

2 A facsimile of Richard Pynson’s 1502 printing of the Sarum processional is published in Use of Sarum I.

3 The three-part setting in late fifteenth-century style is by Andrea Budgey, of the medieval ensemble Sine Nomine.

4 Tone 1 for Psalm 110, Liber Usualis 133.

5 The Sarum version is taken from Processionale ad usum Sarum (Pynson, 1502), fols. 123v–124; the Trent version is in R. von Ficker, ed., Sieben Trienter Codices VI, p. 80. Forest’s first name is unknown.

6 Rastall, Minstrels Playing, p. 461.

7 Rastall, Heaven Singing, pp. 66–71; Minstrels Playing, p. 185.

8 Pammelia (London, 1609; STC 20759) contains three songs from Beaumont’s Knight of the Burning Pestle; Deuteromelia (London, 1609; STC 20757) contains a further song from the same play, as well as songs from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night and Marston’s Jack Drum’s Entertainment; Melismata (London, 1611; STC 20758) is a collection of humorous “city” and “country” songs, many of which may have dramatic connections.

9 The faubourdon setting of the tune is by Garry Crighton of the University of Münster.

10 Stevens, Music at the Court of Henry VIII, pp. 78–79.

11 The full text of the poem may be found in Salisbury, Trials and Joys of Marriage, p. 253.

12 Fallows, “Gresley Dance Collection, c. 1500.”

13 Nevile, “Dance in Early Tudor England.”

14 Guglielmo Ebreo of Pesaro, De pratica seu arte tripudii.

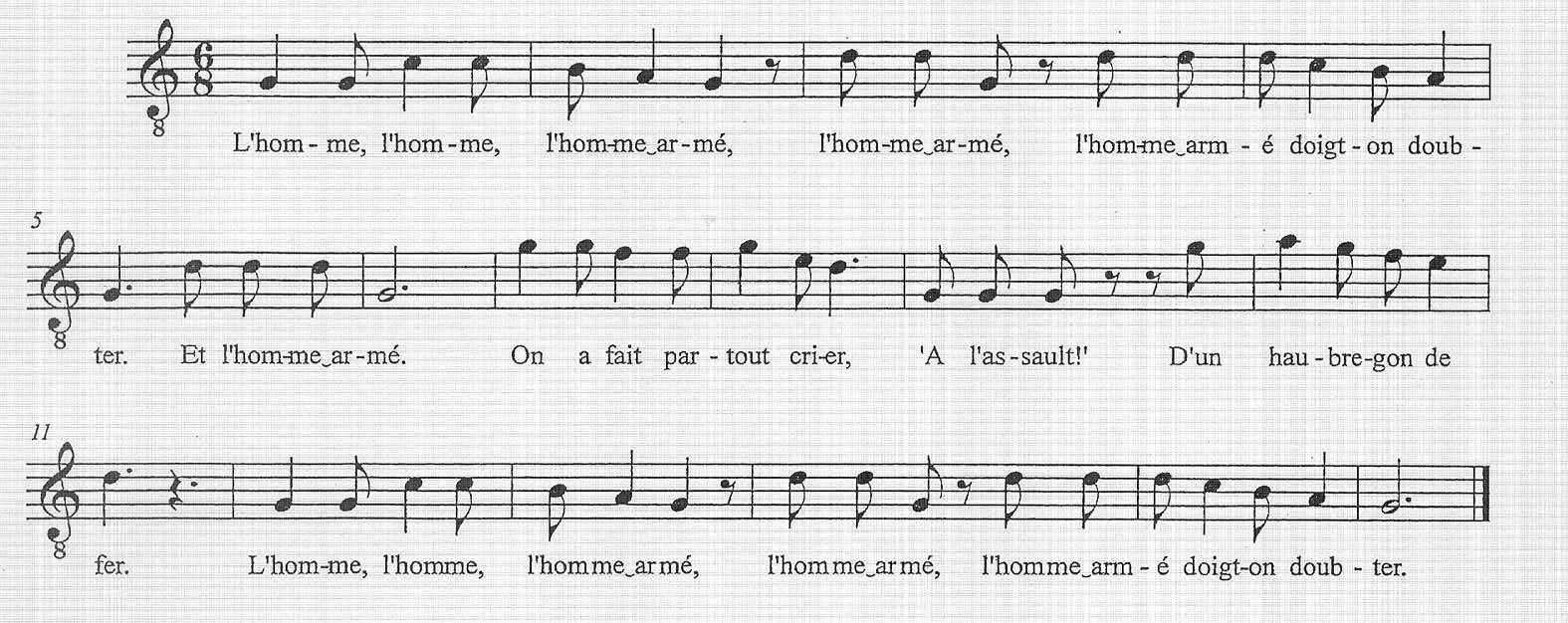

The only explicit indication of music in The Pride of Life is the direction that the king’s messenger, Mirth, sing a song (line 322, s.d.) as he takes the queen’s message to the bishop, perhaps moving from one scaffold or stage to another. The dramatic situation only requires that the song mirror Mirth’s high spirits. Very few secular songs survive from the later fourteenth century, but one possibility would be the popular song “L’homme armé,” which appears in a variety of polyphonic settings. These all date from later in the fifteenth century, but the tune itself is likely to have been significantly older. There is no reason why the messenger should not sing a song in French, though it is not certain that the tune was known in England.

MUSIC IN WISDOM

The stage directions of Wisdom specify an unusually extensive use of music, utilizing plainchant, secular polyphony, and dance music. Since in some cases the chant is sung by five or six people, there is also the possibility that some of the liturgical texts might have been sung in polyphonic versions. This appendix provides the music for the relevant chants in the Sarum usage, as well (in two cases) as polyphonic settings of the sort which might have been used.1

THE LITURGICAL MUSIC

The most likely source for the liturgical texts which are sung in the play would be the monophonic plainchant of the Sarum rite, which was instituted under the guidance of St. Osmund, who became bishop of Salisbury (Sarum) in 1078 and which remained the primary liturgical usage in the south of England until the Reformation.2

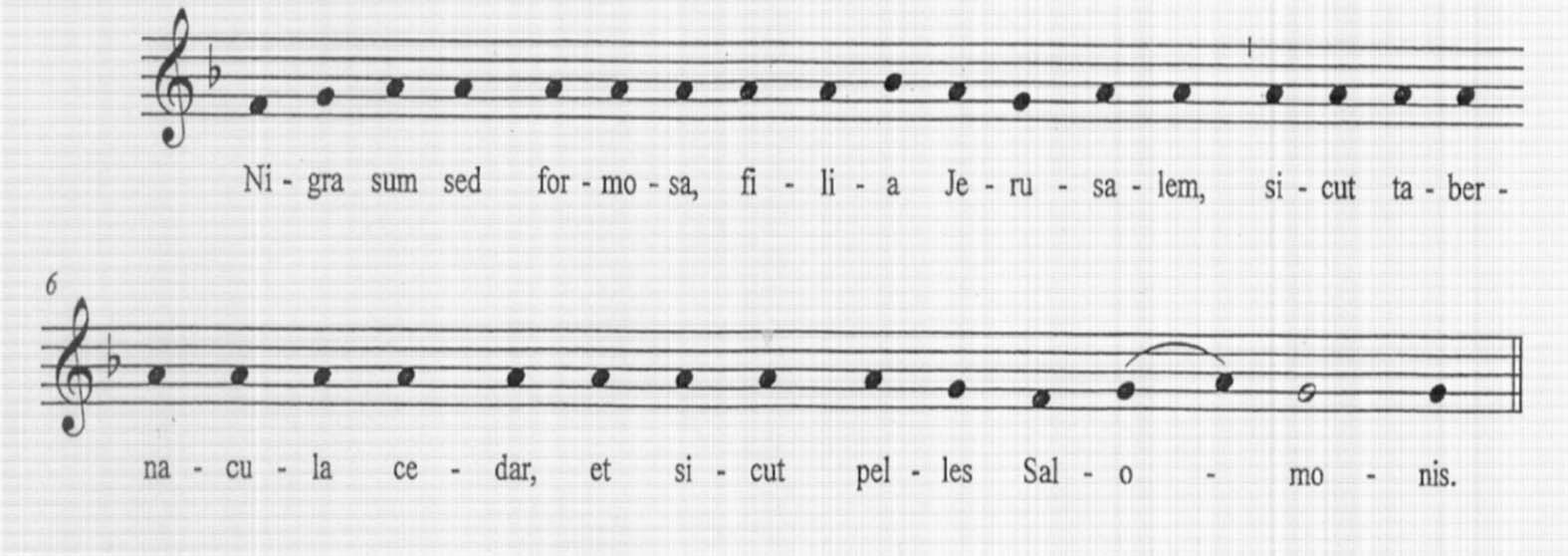

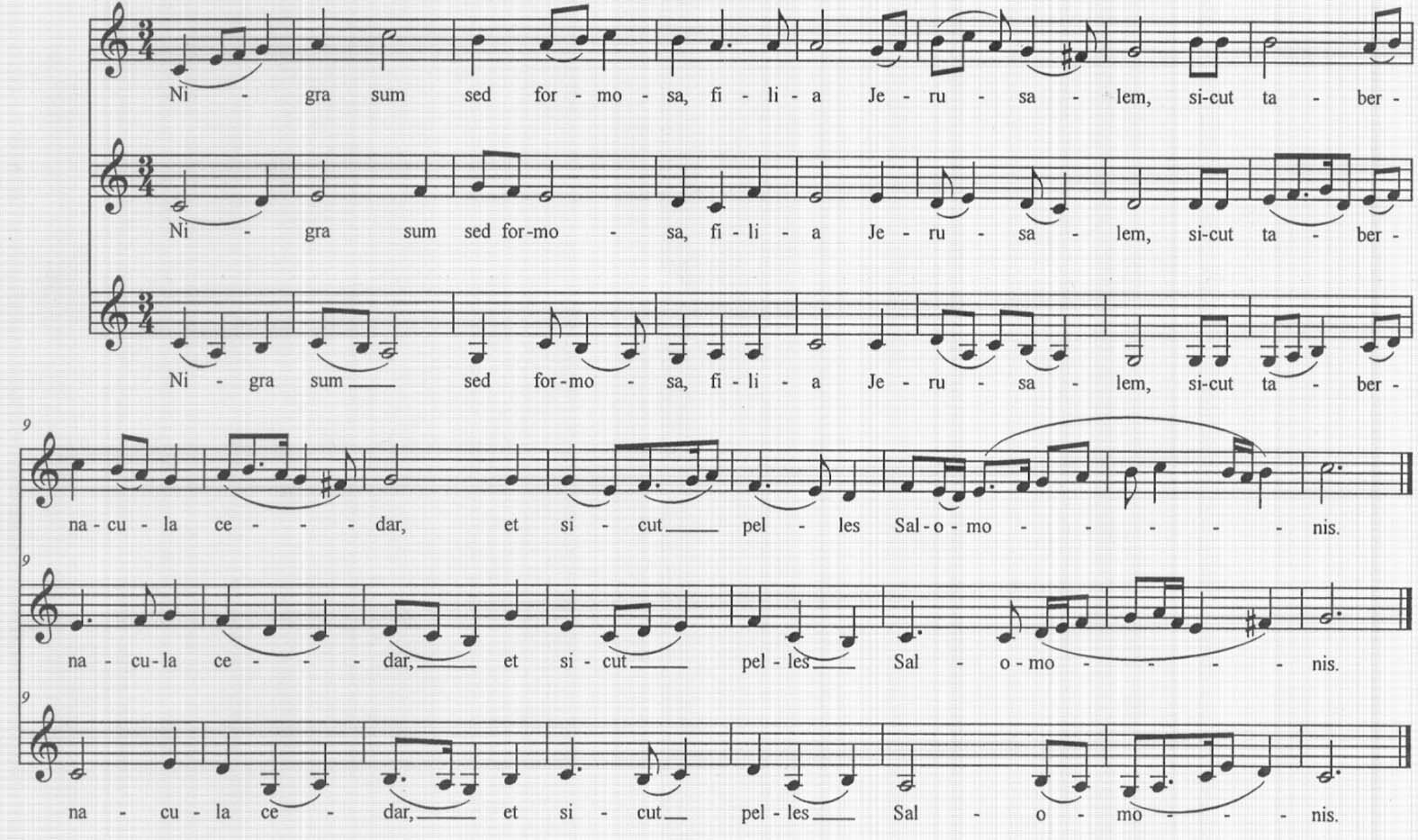

The processional antiphon “Nigra sum” (line164, s.d.) with which the Five Wits enter is given in two versions: a chant and a three-part setting.3 The text is from Canticles1:4, which does not appear in the liturgy, so I have set it to a suitable psalm tone.4 If the chant version is used, it would be appropriate for Anima to sing the first line as an intonation (as Rastall suggests), the Five Wits joining her on the words “filia Jerusalem.”

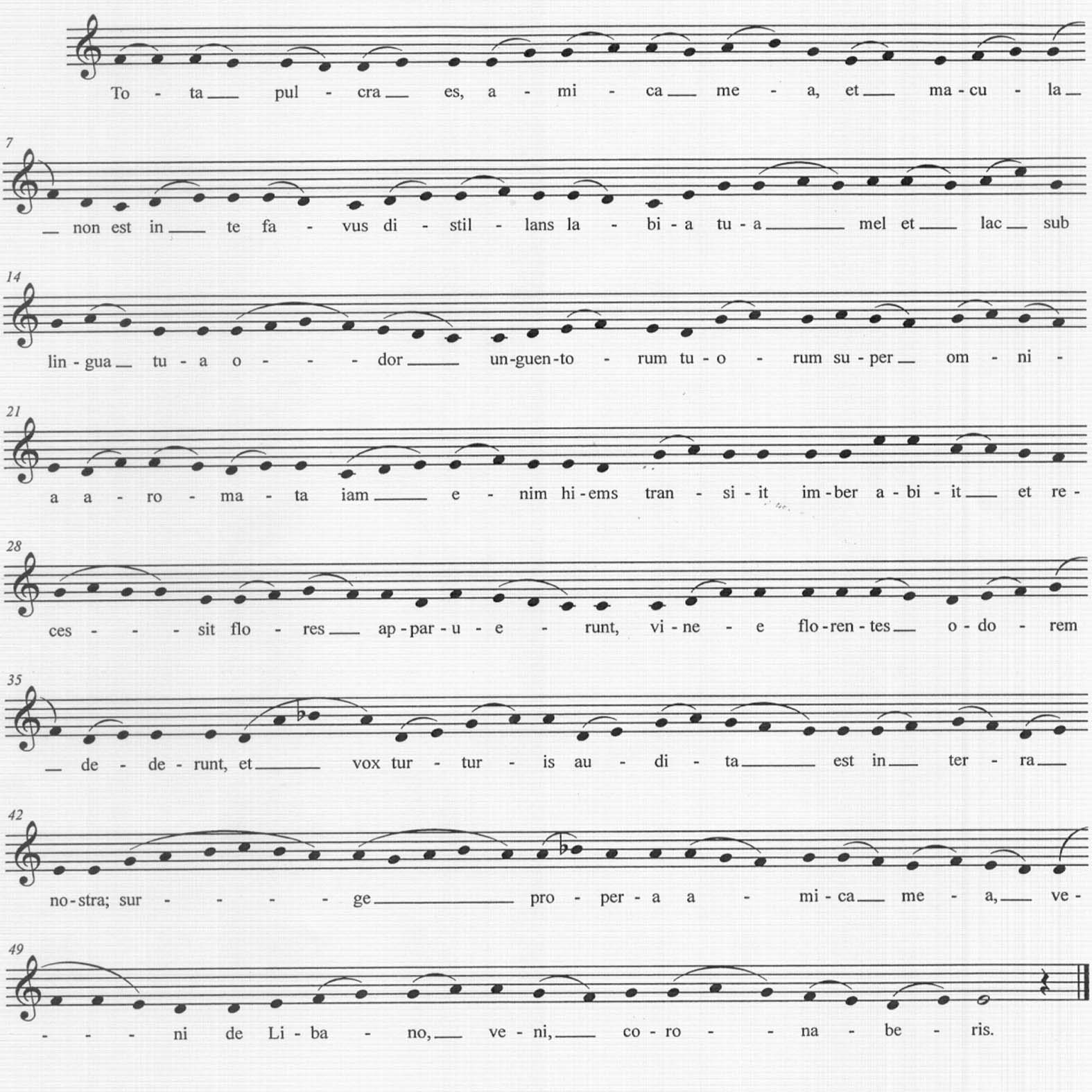

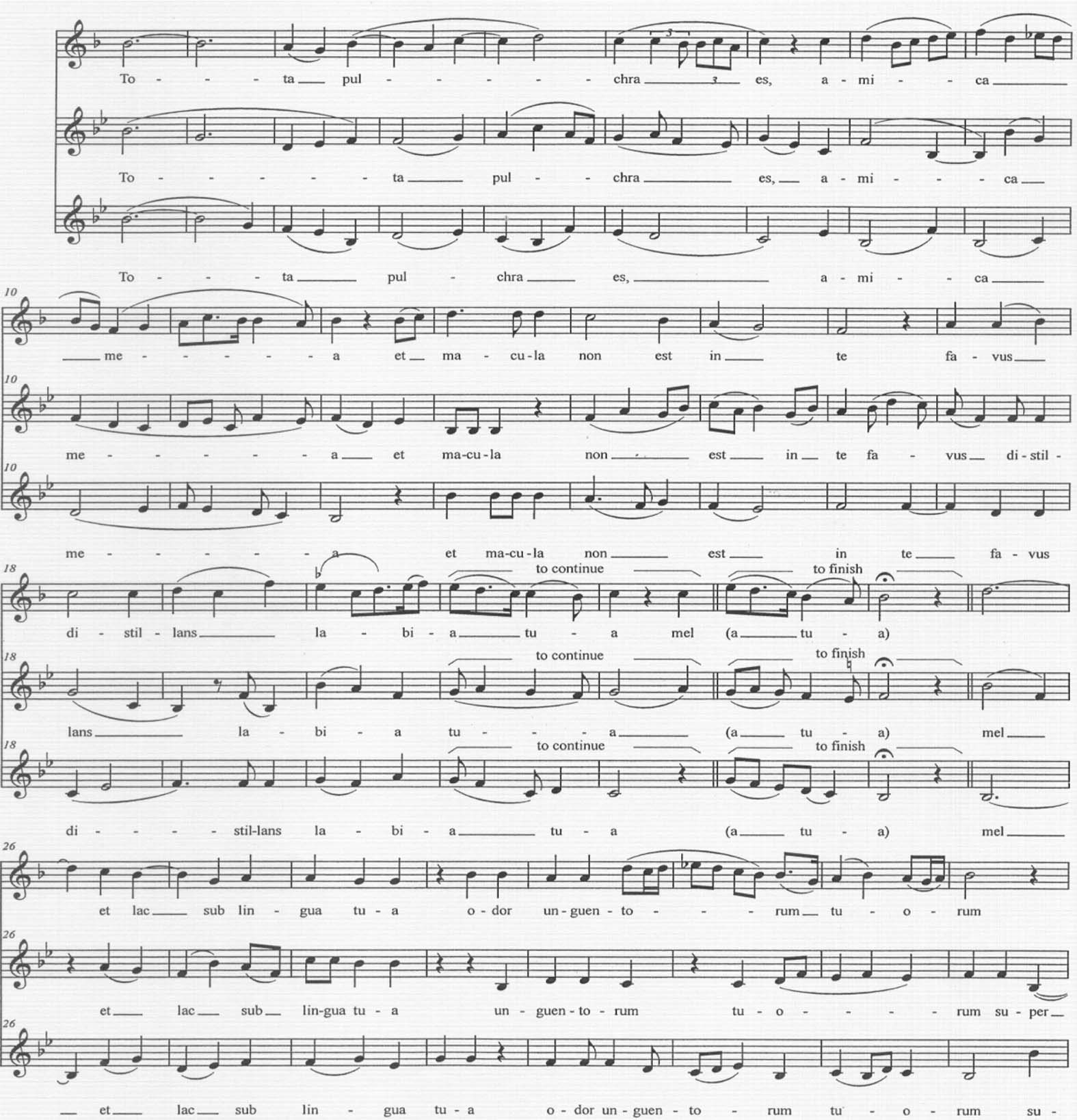

The processional antiphon which ends the first section of the play, “Tota pulcra es” (line 324, s.d.), is given here both in its Sarum form and in a three-part setting by Forest from the Trent manuscripts.5 This collection of sacred music was compiled between about 1415 and 1421, so this setting may be a bit too early for the play. It is important to note here that the text is not one of the Marian antiphons beginning “Tota pulcra es Maria,” but is derived from Canticles 4:7–11 and 2:11–13.

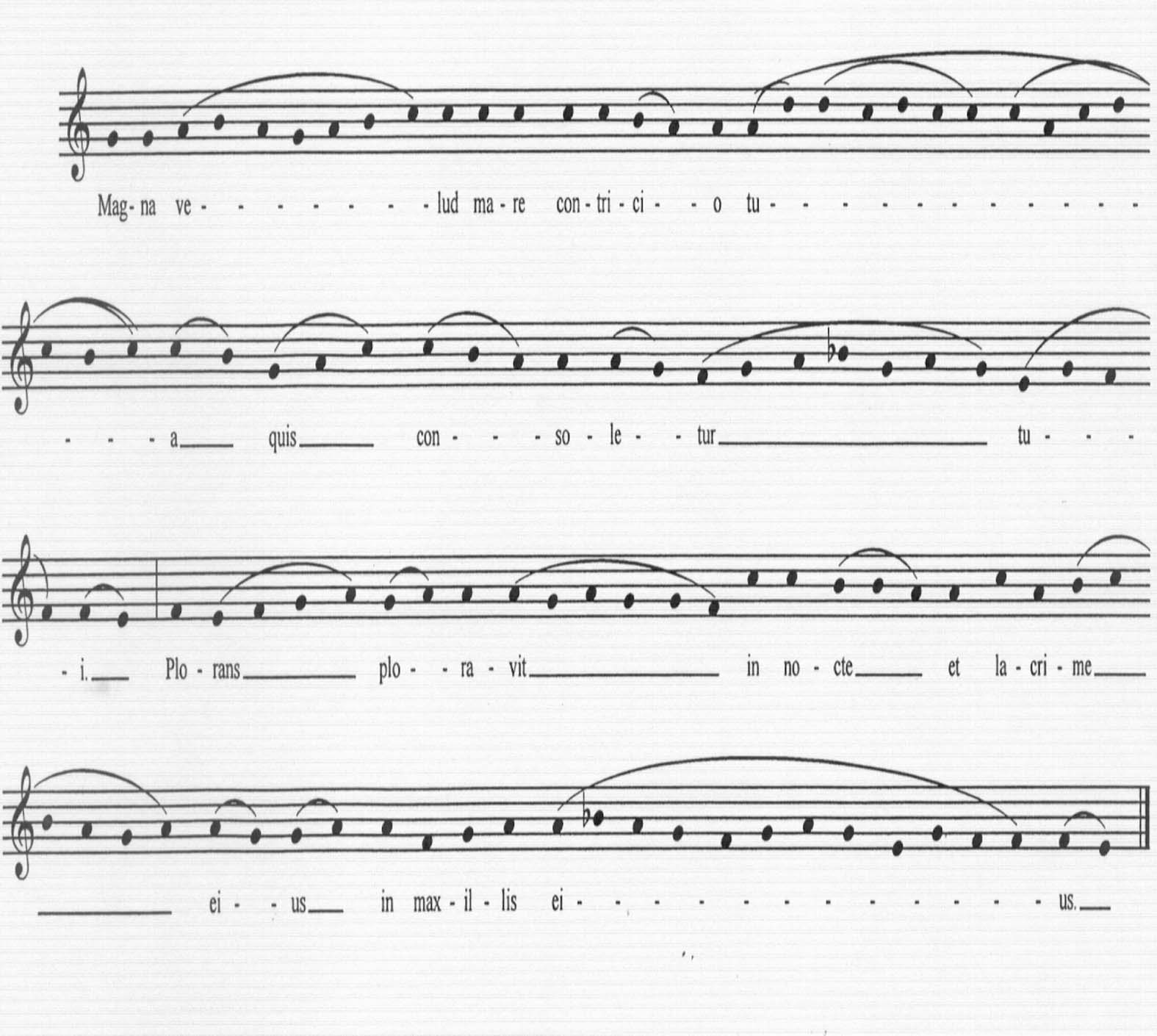

The two verses which Anima sings processionally “in the most lamentabull wyse” (line 996, s.d.) as she and the Mights leave the stage to receive penance are both from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, and thus both appear in the Easter liturgy; the first, “Magna velud mare contricio” at matins on Good Friday; the second, “Plorans ploravit” at matins on Maundy Thursday the day before. Since they come from two different services, it is not clear how the two verses would be sung, but the two most likely possibilities are either that the verses would have been extracted from the larger settings of the Lamentations and sung successively, or that a newly-composed setting would have been made. I have given the chants for the two verses as they appear in the Easter liturgy and have made minor adjustments to the music to reflect minor differences in wording between the Sarum chant and the playtext.

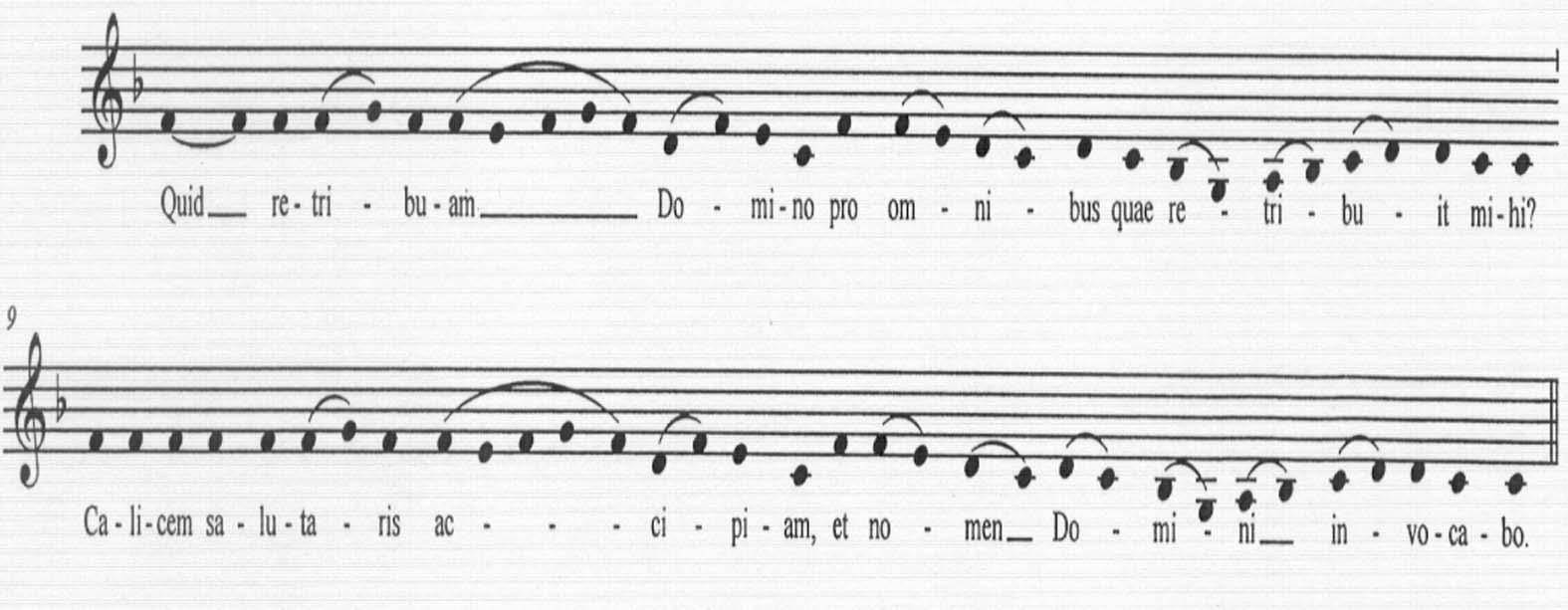

The antiphon “Quid retribuam” with which Anima, her Five Wits, and her three Mights return to the stage transfigured (line 1064, s.d.) is also given in two versions. Since only the second verse, “Calicem salutaris,” appears in the Sarum use I have followed Rastall’s suggestion that the first verse simply be set to the same music.6 The alternative three-part version is simply a setting of the chant in faubourdon style. The parallel harmonies of faubourdon represent one possible method of elevating the solemnity of an occasion, and thus would be appropriate for the final return of Anima and her retinue.

THE THREE-MEN’S SONG

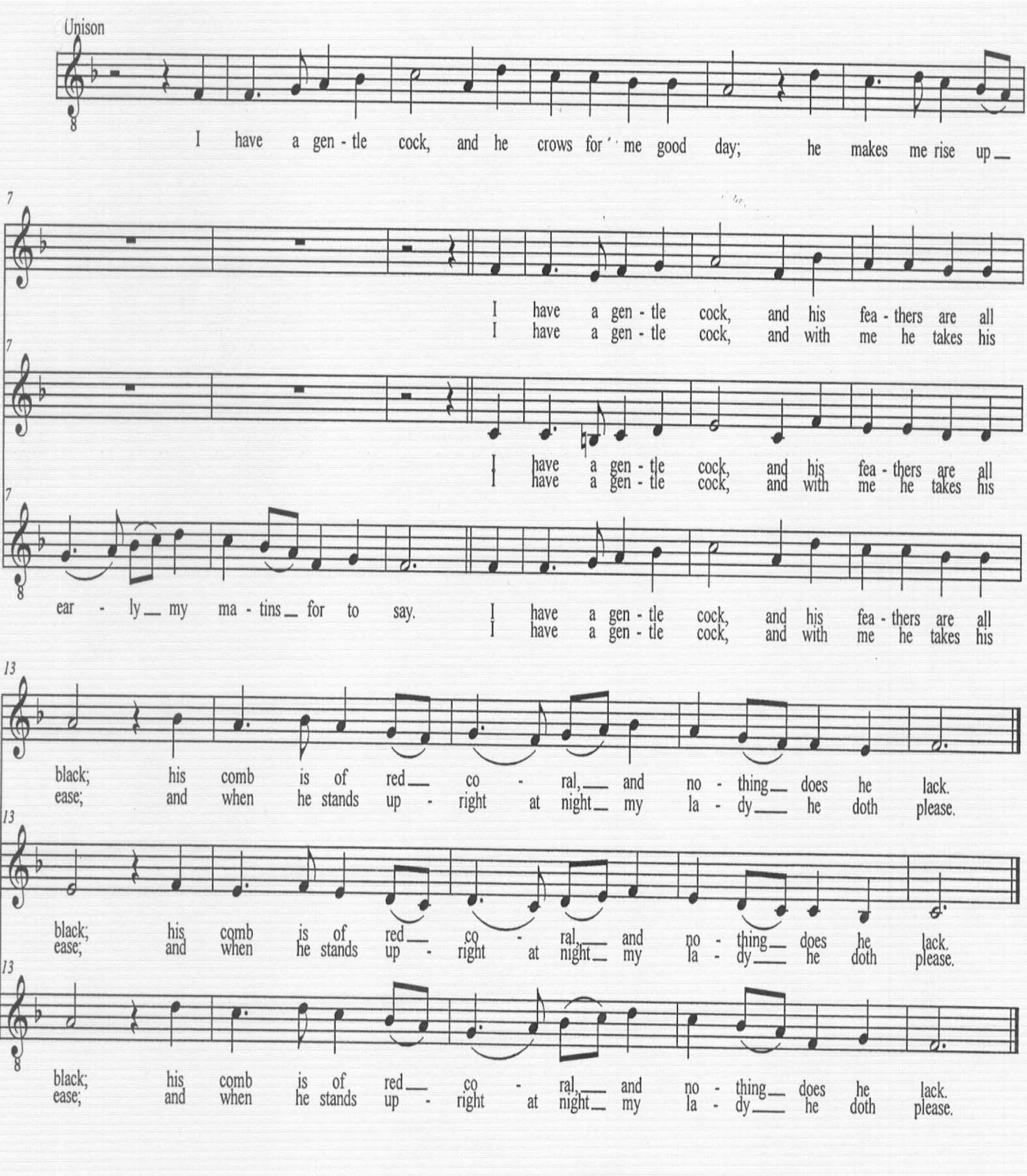

Secular songs for three men’s voices (treble, mean, and tenor) become relatively common towards the end of the fifteenth century, and proliferate in the sixteenth. They appear with some frequency in plays; the best known are the two songs in the Coventry Shearmen and Tailor’s Play, the well-known Coventry Carol and the Shepherds’ Song.7 At least some of the three-part songs collected by Thomas Ravenscroft appear to have had dramatic connections.8 The anonymous three-part song given here has the bawdy quality that seems to be demanded by the play; it also has the advantage that the polyphonic setting of the second and third verse parodies the faubourdon style which was often used in a contemporary liturgical context.9 The tune appears in a five-part setting in the Henry VIII manuscript (British Library Add. 31922, fols. 106v–107r) with the words “And [If] I were a maiden, as many one is . . .”10 I have extracted the preexisting tune from the tenor part and reset it to a text based loosely on the fifteenth-century secular lyric, “I have a gentil cok.”11

THE DANCES

I have not given music for the dances. The sources which survive for English dance music at the end of the fifteenth century are very slim, and the largest single collection, the dances from Gresley Hall, Derbyshire, do not fit the instruments specified in the playtext.12 The stage directions indicate the instruments for each of the three dances: trumpets for Mind’s dance of maintenance, a bagpipe for Understanding’s jurors, and a hornpipe for Will’s dance of lechery. There is no indication of how many trumpets accompany the first dance, but clearly the other two dances use only a single instrument. The Gresley dances, like much other dance music from the period, require at least two players, since they consist of an elaborate (often improvised) treble played over a preexisting tenor. In the case of many dances, including those of the Gresley collection, it is only this tenor part which survives, with the expectation that one or more parts would be improvised above it. The most extensive sources for monophonic dances are Italian, and Jennifer Nevile has suggested that Italian dances may not have been unknown in late fifteenth-century England.13 If this solution is adopted, the most useful source for both music and choreography is the 1463 dance treatise of Guglielmo Ebreo of Pesaro.14

A POSSIBLE SONG FOR NUNCIUS, LINE 322S.D.

TO LINE 164, “NIGRA SUM SED FORMOSA,” CHANT VERSION

TO LINE 164, “NIGRA SUM SED FORMOSA,” POLYPHONIC VERSION

Andrea Budgey

TO LINE 324S.D., “TOTA PULCHRA ES,” CHANT VERSION

TO LINE 324S.D., “TOTA PULCHRA ES,” POLYPHONIC VERSION

Forest

TO LINE 619S.D., SONG FOR MIND, WILL, AND UNDERSTANDING

TO LINE 995, “MAGNA VELUD MARE CONTRICIO”

TO LINE 1065S.D., “QUID RETRIBUAM DOMINO,” CHANT VERSION

Go To Bibliography