Guy of Gisborne: "Why a spoon, cousin? Why not an axe?"

Sheriff: "Because it's dull, you twit. It'll hurt more."

—Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)

The sheriff of Nottingham's role in the Robin Hood legends is not glamorous – nor is his rivalry with Robin Hood particularly personal. In sum, the sheriff exists because Robin Hood needs the sheriff to exist. Without a foe who embodies local and national governmental corruption, indicating both personal failings and systemic problems,Robin Hood cannot hope to stand as a resistance figure to unjust authority. Consequently, the sheriff of Nottingham is rarely granted so much as a personal name. Certainly in the late medieval / early modern ballad tradition the sheriff serves more as an incompetent stock villain over whom the protagonist – for the early Robin Hood can hardly be called a hero – continually triumphs. The narrative continuity that many modern audiences expect from serial productions on the same topic is not present in the medieval Robin Hood materials; Robin is not the same "person" from story to story. Nor is the sheriff the same "person": the sheriff is killed in The Geste of Robyn Hode and in Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne because they are separate stories and are not intended to cohere.

Modernity has not been kind to the sheriff (though his survival rate has generally improved) and he has barely escaped that early anonymity in modern film and literature. Even in modern film productions the character is still often unnamed,

...Read More

Read Less

Sheriff, to Robin Hood: "I'll cut your heart out with a spoon!"

Guy of Gisborne: "Why a spoon, cousin? Why not an axe?"

Sheriff: "Because it's dull, you twit. It'll hurt more."

—Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)

The sheriff of Nottingham's role in the Robin Hood legends is not glamorous – nor is his rivalry with Robin Hood particularly personal. In sum, the sheriff exists because Robin Hood needs the sheriff to exist. Without a foe who embodies local and national governmental corruption, indicating both personal failings and systemic problems,Robin Hood cannot hope to stand as a resistance figure to unjust authority. Consequently, the sheriff of Nottingham is rarely granted so much as a personal name. Certainly in the late medieval / early modern ballad tradition the sheriff serves more as an incompetent stock villain over whom the protagonist – for the early Robin Hood can hardly be called a hero – continually triumphs. The narrative continuity that many modern audiences expect from serial productions on the same topic is not present in the medieval Robin Hood materials; Robin is not the same "person" from story to story. Nor is the sheriff the same "person": the sheriff is killed in The Geste of Robyn Hode and in Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne because they are separate stories and are not intended to cohere.

Modernity has not been kind to the sheriff (though his survival rate has generally improved) and he has barely escaped that early anonymity in modern film and literature. Even in modern film productions the character is still often unnamed, largely because he continues to serve as an identifiable stock villain. When the sheriff appears in modern productions, his second in command, Guy of Gisborne, frequently steals the show. The exception to this rule is when the sheriff is played as utterly crazed and insane: for example, in the television series Robin of Sherwood and the feature film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, where the sheriff's antics draw more narrative and audience attention than his position as Robin Hood's chief enemy.

Thus, until the 1970s, the history of the sheriff of Nottingham as a character was a virtual tabula rasa. Every novel, film, television series, or other media production which felt the need to include the sheriff used the character differently, and with little lasting impact. Late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century cinematic tastes for consistent characterization have produced more detailed "stock" characteristics for the sheriff. However, the sheriff of Nottingham has been appearing alongside Robin Hood since the fifteenth century and, like his nemesis, his history is complex.

What follows is a brief analysis of the sheriff of Nottingham's appearances and history during three major periods of the tradition's development: the earliest materials available, up to the end of the fifteenth century (EARLY), the stepping stone texts of the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries (MIDDLE), and the advent of film and novels in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (MODERN).

EARLY

In the early literary tradition of Robin Hood the sheriff is always identified with Nottingham: the ballads may be located in Barnsdale, Sherwood, or an unnamed greenwood, but the sheriff is always associated with Nottingham, and no other urban area. Only in Robin Hood and the Monk (circa 1450) is the sheriff not explicitly named as the "sheriff of Nottingham"; instead, when Robin attends church in Nottingham, the monk runs out into the streets to find the sheriff. Thus, though his outlaw opponent shifts easily from location to location, the sheriff's authority and identity are, uniquely, anchored to a single place.

Historical sheriffs would have dealt with any outlaws operating within each sheriff's jurisdiction. However, the early ballads are not consistent in the names attributed to the forest Robin Hood inhabits. Sherwood is within the confines of Nottinghamshire and would fall under the authority of a sheriff based in Nottingham, but that forest is so-named only in Robin Hood and the Monk. A fragmentary play, Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham (circa 1475), connects the sheriff to Nottingham in the title alone – the town name does not appear in the play itself. The title seems to derive from a reference made by Sir John Paston in a 1473 letter, and the connection between the sheriff and Nottingham has been created by modern scholars. In two other early ballads, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (likely composed 1475-1500) and A Geste of Robyn Hode (circa 1500), the forest is named as Barnsdale. Walter Bower's Continuation in the 1440s of John of Fordun's Scotichronicon also specifically mentions Barnsdale. Barnsdale – whether the Rutland Barnsdale or the Yorkshire Barnsdale – is categorically outside the jurisdiction of a sheriff using Nottingham as his seat. By contrast, the fourth of the early ballads, Robin Hood and the Potter (circa 1450-1500), declines to name the forest and refers to it only as the greenwood.

In fact, medieval English sheriffs administered entire counties, not single municipalities, and the sheriff of "Nottingham" had two counties – Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire – under his authority. This merging of the two counties appears to have begun with the establishment of the Anglo-Norman shrieval system after the Conquest in 1066. Administration of the two shires was separated in the 1560s, half a millennium after the Conquest and more than a century after the date (1450) most modern scholars assign to Robin Hood and the Monk, the earliest extant Robin Hood ballad.

William Alfred Morris observes that the similarities between the pre-Conquest Anglo-Saxon English sheriff and the Norman vicomté were marked out by the Norman leadership, "[y]et the Conqueror did not bodily transplant the Norman office. The legal basis of his shrievalty was that of Edward the Confessor" because "[t]he history, character and tradition of the English county were very different from those of the Norman vicomté" (Morris 42), and thus accommodations were made. The Norman model, notably, lacked the term lengths that characterize the legal ideal (if not the practice) of the post-Conquest office, particularly after more than two hundred years of negotiation, adjustment, and reforms. These reforms of the shrievalty resulted in an office in which "the sheriff [had] evolved from a regional dictator with true executive authority into a tightly regulated bureaucrat whose chief administrative purpose was to respond to a multiplicity of royal writs" (Gorski 2), and whose term of office was, theoretically (and often only theoretically), a single year. The term limits were put in place to limit the personal authority of sheriffs, but as Gorski observes, "[t]he later medieval sheriff's lack of personal authority was offset by his continued importance as an administrative link between the centre and the localities" (Gorski 3).

J. R. Maddicott argues that the issues preoccupying the medieval ballads, such as "[d]istraint of knighthood [the compulsion to accept knighthood due to fees or size of estate holdings], a corrupt sheriff, and the business of the forest could as well belong to the fourteenth century as to the thirteenth; while the social conventions which the ballads cite, the absence of references to Robin Hood before 1377 and their proliferation thereafter, all provide very strong evidence for an early fourteenth-century origin" (Maddicott 237-38). However, as Gorski notes, fourteenth-century sheriffs "held various other local offices during their careers and were therefore part of a much larger 'office-holding group' or, perhaps, an 'office-holding community'" (Gorski 7),which puts the ballads' sustained dislike of the office of the sheriff into a context much larger than a single corrupt individual. Thus, the sheriff of Nottingham goes unnamed because the ballads' objections and concerns are not with any particular person, but with a concept embodied in the sheriff's office.

Less effort has been made to locate the "real" sheriff of Nottingham than the "real" Robin Hood. Scholars have, however, identified several potential candidates. Maddicott favors John de Oxenford, whose term of office as sheriff of Nottinghamshire and Derby began erratically: the List of Sheriffs for England and Wales indicates de Oxenford served from February to March of 1334, resuming his post in July and retaining it until June 1335, finally serving a continuous three-year term between March 1336 and March 1339. Maddicott calls attention to de Oxenford's unusually checkered reputation in support of his candidacy. However, Gorski makes the case for Thomas de Bekeryng the younger, whose list of criminal offenses is as lengthy as de Oxenford's, and who seems to have replaced de Oxenford in 1335. In modern popular fictional representations of the sheriff, some artists like author Richard Kluger and the creators of Robin of Sherwood have drawn from the List of Sheriffs and selected the name of Philip Marc, who served in 1209, 1214 and 1217. These three candidates – separated by more than a hundred years and nearly as many occupants of the sheriff's office – are considered potential "inspirations" for the fictional sheriff. Notably, none of these men served during the specific periods that candidates for the title of the "real" Robin Hood appear in legal and other records. Joseph Hunter's candidate, "Robert Hode," was presumed to be active in 1324 and potentially connected to another man of the same name mentioned in 1317, in Yorkshire; L. V. D. Owen's candidate comes to notice in 1225-26 in Wetherby, North Yorkshire; and J. R. Planché's candidate was active in 1203 in Warwickshire. None of these counties are within the sheriff of Nottinghamshire and Derby's jurisdiction, and none of these potential "real Robin Hoods" would have had significant contact with the candidates for the "real sheriff of Nottingham." As with the search for the "real" Robin Hood, the search for the "real" sheriff of Nottingham remains an exercise in futility.

MIDDLE

A more fruitful avenue of research lies in examining the connections between the Robin Hood tradition and explicit political agendas. The Tudor era's interest in the sheriff of Nottingham goes hand in hand with the period's revival of interest in the traditional Robin Hood material. Sir Richard Morison's "A Discourse Touching the Reformation of the Lawes of England," dated by Sydney Anglo to 1542, is addressed to Henry VIII of England, a monarch who is known to have significantly enjoyed the Robin Hood tradition. Morison's pamphlet explicitly invokes Robin Hood, Maid Marian, and Friar Tuck in the context of plays which promote "lewdenes and rebawdry that ther is opened to the people, disobedience also to your officers, is tought, whilest these good bloodes go about to take from the shiref of Notyngham one that for offendying the lawes shulde have suffered execution" (qtd. in Anglo 179). The reference here to the sheriff of Nottingham aligns the figure with the forces of law and order, besieged by works of fiction which normalize civil disobedience and criminal action and thus promote social unrest. In Morison's context, the sheriff of Nottingham is targeted because of his connections to the king, enabling Morison to make a case for the plays to be "forbodden and deleted and others dyvysed to set forthe … and to declare and open to them thobedience that your subiectes by goddes and mans lawes owe unto your magestie" (qtd. in Anglo 179).

A generation later, Anthony Mundy wrote two late Elizabethan plays, The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1598) and The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1599). The Downfall notably fails to include the sheriff but he appears repeatedly in The Death. In The Death, the office is filled in sequence by two different characters: an unnamed man whose role is then assumed by Justice Warman. Warman is also the false and traitorous steward to Robert, Earl of Huntingdon. The Mundy plays are interesting for their elevation of the Robin Hood figure to a noble rank, with subsequent modifications to the traditional material necessary to support the new conceptualization of Robin Hood as a dispossessed nobleman. Knight and Ohlgren note in their introduction to the play that "[t]he politics of the play, like so many other historical dramas of the period, operate across the complex quadrilateral of crown, clergy, barons and bureaucrats, a force field which is evidently late sixteenth century in its reference" (Knight and Ohlgren 297). Warman functions as a Judas figure, as well as a representative of the often-corrupt shrieval office, though Knight and Ohlgren hasten to add that this corruption is not extended to the crown, since John "himself is not the villain that in more personalized modern dramas he has become: hot-tempered though he is, having taken power he is easily dislodged and in fact takes to the forest himself, fights a 'joining the band' duel with the friar, and plays the role of Marian's somewhat over-enthusiastic admirer" (Knight and Ohlgren 297).

The political treatment of Robin Hood continued in Martin Parker's 1632 A True Tale of Robin Hood. Parker's Robin Hood preemptively castrates monks and friars to prevent them from filling the country with bastards (69-72), as well as to punish them if they resist his robberies (65-68), and Parker "works through a whole series of lessons to be drawn in a cautious, conservative way from this account" (Knight and Ohlgren 603). Robin's enemies are the clergy and the Church, and not in any way the state; in his lessoning, Parker claims that men living in "these latter dayes / Of civill government" (433-34) are not as a barberous as they were in the middle ages, and now, "God be thanked! People feare / More to offend the law" (439-40). Despite – or perhaps because of – this respect for the law, the sheriff of Nottingham is conspicuous in his absence from Parker's story. The rich Abbot of Saint Mary's abbey petitions the king directly and does not deal with the king's representative, the sheriff (113-16); when the king decides to take action after collecting his rents (129-32) he sends "Full many yeomen bold" (146) to deal with Robin Hood, but Robin entertains and charms these yeomen (149-60). Thus, the king "to take him, more and more / Sent men of mickle might" (161-62), but never once does he resort to the law enforcement systems that are theoretically in place in the locality. This indicates, particularly in light of Parker's enthusiastic statements regarding the rule of law, that the sheriff is seen so firmly as a villain that he cannot be included in the tale as anything else. In order for Parker to produce an anti-clerical and pro-government story he must remove the sheriff entirely, even when the basic plot demands the figure's presence.

Likewise, the sheriff is notable in his absence in the Reformation play Robin Hood and His Crewe of Souldiers, performed August 23, 1661, in Nottingham – the day of Charles II's coronation. The presence of a messenger – likely from the King – satisfies the need for an official voice without offering the confusion that the sheriff of Nottingham (in the context of a Robin Hood story, despite the play's performance in Nottingham) would likely present to audiences. The messenger says the king "offers Life, and / Peace, and Honour, if you will quit your wilde rebellions, and become what / your birth challenges of you, nay what ever your boasted gallantry expects of / you that is: loyall subjects" (l. 125-28). The Robin Hood of this story abruptly reverses his dangerously subversive position – "I am quite another man; / thaw'd into conscience of my Crime & Duty; melted into loyalty & respect to / vertue" (l. 131-33) – and accepts a pardon while avowing loyalty. Knight and Ohlgren note that "it is striking how many of the texts from this period effectively divert the resistant force of the hero into less radical modes [....] with this short play as the political cutting edge of that reformed figure" (442). Though this play neutralizes the threat represented by Robin Hood, the absence of Robin Hood's long-time foe is the key element which allows the story to continue the process of politicizing the tradition.

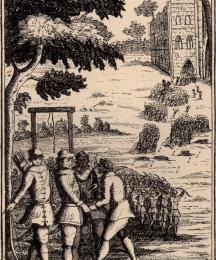

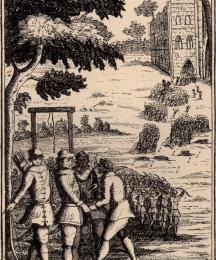

The sheriff is largely absent in the later broadside ballads of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. He makes a cursory appearance in the late eighteenth-century ballad Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow and plays a more pivotal role in both the A and B versions of Robin Hood and the Butcher (second half of the seventeenth century), a retelling of the medieval ballad Robin Hood and the Potter. The sheriff is also the villain the Percy Folio (1663) ballad Robin Hood Rescues Three Young Men and is hung by the outlaws at the end of that story; presumably the ballad's close relative Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires ends similarly, though that variant text is incomplete. Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow opens with the sheriff taking his complaints of Robin Hood to King Richard, and the archery contest is the result of the king's order to "Go get thee gone, and by thyself / Devise some tricking game / For to enthral yon rebels all" (14-16). The figure of the sheriff appears in the late seventeenth-century ballad Robin Hood and the Beggar I (but not the later Robin Hood and the Beggar II), The King's Disguise, and Friendship With Robin Hood (circa middle 1700s, not later than 1753), and Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly (circa 1723). Most interestingly, despite its gruesome topic and staggering body count, the King's representative of law and order does not present himself to be slaughtered in the blood-thirsty ballad Robin Hood's Progress to Nottingham (circa 1656).

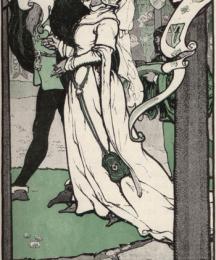

Despite a revival of interest in the Robin Hood tradition in the opening decades of the nineteenth century, the sheriff of Nottingham remains in the background until the end of the century. The landmark book by Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire (1883), features the sheriff quite prominently. Perhaps because of the increased awareness Pyle's book brought to the figure, the sheriff subsequently appears as one of the major villains in the pair of light operas produced by Reginald De Koven and Harry B. Smith, Robin Hood (1890) and Maid Marian (1901).

MODERN

In the modern period (the twentieth century forward), film has become the major medium for the Robin Hood tradition. The sheriff's portrayal and treatment in the cinematic tradition began slowly, reflecting his precarious and secondary placement in the early written materials of the tradition. The sheriff is rarely named; he usually appears as Prince John's toadying stooge; he is consistently overshadowed by the dynamic and handsome actors selected to play Sir Guy of Gisborne. This is certainly true in the two most prominent early Robin Hood films, Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood (1922) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Neither sheriff has a personal name: William Lowery and Melville Cooper's performance credits are as "the High Sheriff of Nottingham," characters with no personal names. Both performances reduce the sheriff to the background of the film. Guy of Gisborne becomes the active agent of the corrupt shrieval system, and often – certainly the case in the 1922 and 1938 films – Robin Hood's romantic rival for the hand of Maid Marian. Gisborne's sexual menace towards Marian is inevitably seen as more threatening than the sheriff's bumbling incompetence. In the 1950s television program The Adventures of Robin Hood (starring Richard Greene as Robin Hood), Alan Wheatley's sheriff appears to be in love with Bernadette O'Farrell's Maid Marian, but (fitting for the program's general target audience) his admiration is never portrayed as threatening to either Marian or Robin. Instead, Wheatley's sheriff is a harmless villain used to set up the day's adventure.

The 1970s saw two significant cinematic Robin Hood productions which moved the character forward significantly. The first was Wolfgang Reitherman's 1973 animated film Robin Hood, a product of the Disney animation department, which subsequently proved a favorite for many children. In this film, which features Robin Hood as a cheery fox, Little John as an affable bear, and Friar Tuck as a badger, the sheriff is portrayed as a portly wolf and voiced by Pat Buttram. The symbolism of the sheriff-as-wolf is blatant and his actions further categorize this sheriff as "evil" – he steals from the hard-working poor who have been injured on the job, widows with large families, and charitable churchmen. Furthermore, this sheriff exhibits no remorse. The vocal performance evokes cinematic conventions of lawmen in Western movies and of menace thinly veiled by lip-service to the law.

The second film is Richard Lester's 1976 Robin and Marian, starring Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn as Robin Hood and Maid Marian, and Robert Shaw as the sheriff. In his 1976 review, Roger Ebert notes that Shaw's sheriff is fundamentally a good man, though "grim and patient." Jamie Gillies, a reviewer for apolloguide.com, notes that Shaw "plays the Sheriff of Nottingham with a certain sympathy for Robin Hood. This is bizarre at times and while the two are enemies, he is almost gracious and far from evil." Gillies's review indicates audience preference for a villainous sheriff – a trope which Robin and Marian deliberately seeks to disrupt through Shaw's performance. This disruption is constructed to parallel the complications Lester injects into the figure of Robin Hood.

However, Lester's sympathetic sheriff did not capture the imagination of television and film audiences, though there are novels which have taken up the theme. Rather, the sheriff's character underwent a profound shift when Nickolas Grace was cast in the television show Robin of Sherwood (1984-86). Grace's performance is the model for the modern filmed sheriff: over the top, manic, terrifying in his instability, and a clearly designated target for outlaw resistance. His second-in-command, Guy of Gisborne (played by Robert Addie), takes a back seat to the sheriff's antics. Grace's character, moreover, is one of the first filmed sheriffs to have a proper name: Robert de Rainault. There is no historical sheriff of Nottingham of this name, though when de Rainault is threatened with replacement the candidate is Philip Mark: a man who historically held the office from 1208-09 and again in 1214 (possibly until 1224), though not during the show's setting in the reign of Richard I. Amusingly, Lewis Collins was cast in the role, playing up his typecasting as a hard man.

The Grace performance served as a precedent for Alan Rickman's scene-chewing turn as the sheriff in the Kevin Costner vehicle Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991). Stephen Knight notes that Rickman's overacting "underlines the fact that apart from those rare talents who can fully energize Robin, this is the plum part," though Rickman's "ripe style, while splendid in its own way, quite unbalances the film" (Knight 246). Moreover, Rickman's performance stands out all the more against Costner's own placid and unremarkable showing. However, there were two Robin Hood films produced in 1991, Costner's Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves and John Irvin's Robin Hood (starring Patrick Bergin and Uma Thurman). Irvin's film notably did not feature a sheriff of any type. The movie was sent directly to home video distribution rather than compete against the Costner blockbuster. The film's neglect of the sheriff – a figure present in the tradition from the earliest surviving texts – is surprising given the sheriff's persistence in the cinematic tradition.

The early 1990s brought an unusual clustering of Robin Hood productions. The Costner film inspired a satire, Mel Brook's Robin Hood: Men in Tights in 1993. Though the primary villain is Prince John, Roger Rees's performance as Mervyn, the Sheriff of Rottingham, draws not only on Rickman's performance but on those of Lowery and Cooper as well. The 1997 television series The New Adventures of Robin Hood (starring first Matthew Porretta and later John Bradley as Robin) barely used the sheriff at all. However, the 2006 Tiger Aspect series Robin Hood featured Keith Allen as the vicious and unstable Vaisely, a sheriff in the mode of Grace and Rickman. This sheriff crushes his pet birds to death (in the first episode), suggesting Allen's sheriff is far more menacing and unpredictable than his precursors. Allen's performance does enable the character to hold his own against fan-favorite Richard Armitage's Guy of Gisborne. Unlike Addie and Grace's characters in Robin of Sherwood, Armitage's Guy and Allen's Vaisely share the stage equally.

Matthew Macfadyen's performance as the sheriff in Russell Crowe's film Robin Hood (2010) was low-key and unremarkable, in part because he did not indulge in the histrionics which are becoming traditional thanks to Grace, Rickman, and Allen. However, the sheriff was a very minor character in the 2010 film, and Macfayden's performance will likely not be remembered in the face of the ripe performances of his recent predecessors. The Crowe film is notable for the initial rumors surrounding its plot – early versions of the script were titled Nottingham, and the story was to take the sheriff as its heroic protagonist. Writer Ethan Reiff told Allen W. Wright that Reiff and fellow writer Cyrus Voris approached the project saying, "[l]et's tell Robin Hood from the other guy's point of view. Let's make the Sheriff of Nottingham the hero instead of the villain. ... It was the story of the Sheriff of Nottingham. Like the untold story. I think the tagline on the first page of our script was 'There are two sides to every legend.' We thought it would be interesting and cool and certainly original to tell the story of the sheriff – centered on the sheriff and from the perspective of the sheriff" (Wright Interview). As Wright also notes, Reiff and Voris were apparently not aware of a small but notable tradition of novels which take the sheriff as the positive focus of the Robin Hood tradition.

Richard Kluger's The Sheriff of Nottingham (1991) remains the most substantial novel examining the Robin Hood tradition from the sheriff's point of view. Kluger's sheriff is well-rounded and developed, and Kluger's choice of Philip Mark as the historical candidate necessitates moving the story forward some two decades into the final years of King John's reign, instead of the traditional setting in the reign of John's brother Richard. In 1991 Kluger was not the only novelist experimenting with the traditional setting of the Robin Hood tradition; Parke Godwin produced the novel Sherwood, which provides a sympathetic and well-developed sheriff. Godwin's story is set in the years immediately following the 1066 Conquest of England, and Ralf FitzGerald is an ambitious but compassionate Norman knight unfortunate enough to administer lands during William's enforestment of large swaths of the country. The lands FitzGerald oversees includes those held by the hot-blooded Edward Aelredson who, when he takes to the forest as an outlaw after a legal dispute, adopts the name Robin Hood. Michael Cadnum's young adult novel, In a Dark Wood (1999), features a heroic sheriff hunting for a truly criminal Robin Hood

Kluger, Godwin, and Cadnum are the few authors to focus on the sheriff as a positive character; there are certainly many more whose use of the sheriff is more in line with his traditional role as a villain. Jennifer Roberson's Lady of the Forest (1993) features a sexually predatory sheriff who menaces Marian and plots to force her into marriage through rape; P. C. Doherty's The Assassin in the Greenwood, part of the Hugh Corbet mystery series, uses the sheriff's murder to trigger an investigation which serves as the novel's focus. The surge in Robin Hood novels of the mid-1990s coincides with three significant Robin Hood films. In the twenty-first century, the screenplay by Reiff and Voris indicates ongoing interest in the exploring the character's potential, and the 2006-09 Tiger Aspect television series and the 2010 Universal Pictures film indicate that post-millennial productions are more comfortable using the sheriff as an unqualified villain. The extent of his villainy depends upon the tone of the production. Thus, the Tiger Aspect series embraces the unhinged version of the character. Children's products, such the comic book limited series Muppet Robin Hood (2009), generally feature a clueless and fumbling sheriff who is clearly a tool of the corrupt Prince John.

Just as Robin Hood enjoys a substantial popular-cultural presence, so too does the sheriff have a half-life beyond traditional story-based media. There may not be bumper stickers and political slogans for the sheriff, but there is a band named "The Sheriffs of Nottingham," and transformative fan artists use the title as a pen name. There are works which remove the sheriff – but even these stories raise the question of where the sheriff is and why he is not in the story. Whether the sheriff is named or unnamed, clueless or criminal, featured prominently or in a minor role, the persistent reimagining of the sheriff of Nottingham demonstrates his vital importance in the Robin Hood tradition.

Early

Robin Hood and the Monk (circa 1450)

Robin Hood and the Potter (circa 1450-1500)

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (1475-1500)

Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham (1475)

Middle

Richard Morison, "A Discourse Touching the Reformation of the Lawes of England" (1542)

Anthony Mundy, The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1599)

Martin Parker, A True Tale of Robin Hood (1632)

Robin Hood and His Crewe of Souldiers (1661)

Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow (late 1700s)

Robin Hood and the Butcher A (circa 1650-1700)

Robin Hood and the Butcher B (circa 1650-1700)

Robin Hood Rescues Three Young Men (circa 1600-50)

Robin Hood and the Begger I (late 1600s)

The King's Disguise, and Friendship With Robin Hood (not later than 1753)

Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly (1723)

Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire (1883)

Reginald De Koven and Harry B. Smith, Robin Hood (1890) and Maid Marian (1901)

Modern

Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood (1922). Dir. Allan Dwan. Perf. Douglas Fairbanks (Robin Hood), William Lowery (The High Sheriff of Nottingham).

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Dir. Michael Curtiz and William Keighley. Perf. Errol Flynn (Robin Hood), Melville Cooper (The High Sheriff of Nottingham).

Robin Hood (1973). Dir. Wolfgang Reitherman. Perf. Brian Bedford (Robin Hood – a Fox), Pat Buttram (Sheriff of Nottingham – a Wolf).

Robin and Marian (1976). Dir. Richard Lester. Perf. Sean Connery (Robin Hood), Robert Shaw (Sheriff of Nottingham).

Robin of Sherwood (1984-86). Perf. Michael Praed (Robin Hood-Loxley), Jason Connery (Robin Hood-Huntingdon), Nickolas Grace (Robert de Rainault). Goldcrest / HTV (1984-86).

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991). Dir. Kevin Reynolds. Perf. Kevin Costner (Robin Hood), Alan Rickman (Sheriff of Nottingham).

Richard Kluger, The Sheriff of Nottingham (1991).

Parke Godwin, Sherwood (1991).

Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993). Dir. Mel Brooks. Perf. Cary Elwes (Robin Hood), Roger Rees (Sheriff of Rottingham).

Jennifer Roberson, Lady of the Forest (1993).

P. C. Doherty, The Assassin in the Greenwood (1994).

The New Adventures of Robin Hood (1997-99). Perf. Matthew Porretta (Robin Hood), John Bradley (Robin Hood), Nicholas Clay (Sheriff of Nottingham).

Michael Cadnum, In a Dark Wood (1999).

Robin Hood (2006-09). Perf. Jonas Armstrong (Robin Hood), Keith Allen (Vaisely). BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions.

Tim Beedle, Muppet Robin Hood (2009).

Robin Hood (2010). Dir. Ridley Scott. Perf. Russell Crowe (Robin Hood), Matthew Macfadyen (Sheriff of Nottingham).

Works Cited

Anglo, Sydney. "An Early Tudor Programme for Plays and Other Demonstrations Against the Pope" Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 20.1/2 (1957): 176-79.

Ebert, Roger. "Review: Robin and Marian." April 21, 1976. <http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19760421/REVIEWS/604210301>

Gillies, Jamie. "Review: Robin and Marian." <http://www.apolloguide.com/mov_fullrev.asp?CID=4477> (Site no longer exists)

Gorski, Richard. The Fourteenth-Century Sheriff: English Local Administration in the Late Middle Ages. Rochester: Boydell Press, 2003.

Knight, Stephen and Thomas Ohlgren, eds. Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

Maddicott, J. R. "The Birth and Setting of the Ballads of Robin Hood." Originally published in The English Historical Review 93 (1978): 276-99. Rpt. Robin Hood: An Anthology of Scholarship and Criticism, ed. Stephen Knight (Rochester, NY: D. S. Brewer, 1999).

Morris, William Alfred. The Medieval English Sheriff to 1300. New York: Manchester University Press, 1927; rpt. 1968.

Parker, Martin. A True Tale of Robin Hood. Rpt. in Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Eds. Stephen Knight and Thomas Ohlgren. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

Robin Hood and his Crewe of Souldiers. Rpt. in Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Eds. Stephen Knight and Thomas Ohlgren. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

Wright, Allen W. "Interview: Ethan Reiff: Co-writer of the 2010 Robin Hood film [The original 'Nottingham' screenplay]." <http://boldoutlaw.com/robint/reiff.html>

Additional Scholarly Resources:

Gladwin, Irene. The Sheriff: The Man and His Office. London: Gollancz, 1974.

Great Britain, Public Record Office. List of Sheriffs for England and Wales, from the Earliest Times to AD 1831. PRO Lists and Indexes 9. London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1898; rpt. New York: Kraus Reprint Corp., 1963.

Morris, William Alfred. "The Office of Sheriff in the Early Norman Period." The English Historical Review 33.130 (1918): 145-75.

Musson, Anthony. Medieval Law in Context: The Growth of Legal Consciousness from Magna Carta to the Peasants' Revolt. Manchester, UK and New York: Manchester University Press and Palgrave, 2001.

Read Less

Robin Hood and the Butcher (Child Ballad No. 122A) - 1882-1889 (Author)

Robin Hood and the Butcher (Child Ballad No. 122B) - 1882-1889 (Author)

Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires (Child Ballad No. 140A) - 1882-1889 (Author)

Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly (Child Ballad No. 141) - 1882-1889 (Author)

Robin Hood and the Butcher (Child Ballad No. 122A) - 1882-1889 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Butcher (Child Ballad No. 122B) - 1882-1889 (Editor)

Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires (Child Ballad No. 140A) - 1882-1889 (Editor)

Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly (Child Ballad No. 141) - 1882-1889 (Editor)

A Gest of Robyn Hode - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Potter - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood Rescues Three Young Men - 1997 (Editor)

Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham - 1997 (Editor)

A Gest of Robyn Hode - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Potter - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood Rescues Three Young Men - 1997 (Editor)

Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham - 1997 (Editor)

by Anthony Munday (Author), Stephen Knight (Editor), Thomas H. Ohlgren (Editor), Russell A. Peck (Editor)

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

by James Robinson Planché (Author), Henry Rowley Bishop (Composer)

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

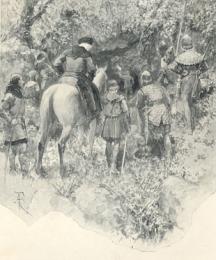

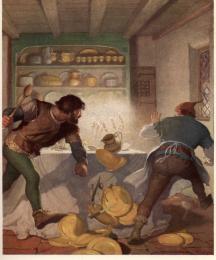

Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly, From the Sheriff and His Men, Who Had Taken Him Prisoner, and Were Going to Hang Him.

Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly, From the Sheriff and His Men, Who Had Taken Him Prisoner, and Were Going to Hang Him.by Anonymous

1723

Images Gallery