Read Less

... Robyn Hode hase many a wilde felow,

I tell you in certen ...

— Robin Hood and the Monk (179-80)

Will Scarlet, also known as Will Scathlock, has long been part of the Robin Hood tradition. He appears in three of the four earliest surviving ballads that form the core of the tradition: Robin Hood and the Monk (c. 1450), Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (c. 1475-1500), and A Gest of Robyn Hode (c. 1500). Members of the outlaw band are sometimes named, and along with Little John and Much, Will Scarlet / Scathlock is a name that consistently appears in the lists of Robin Hood's "wild fellows." However, Will rarely fills any significant narrative role, even in the early tradition: he is one of three outlaws who rescue Robin from the Nottingham jail in Monk; he stands with Robin (and John and Much) in the Gest; he runs away from the Sheriff's seven score men in Guy of Gisborne.

Though Will Scarlet continues to appear in Robin Hood ballads, plays, and early novels, there are few stories which develop the figure prior to the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Novels which focus on Will Scarlet, like What a Scoundrel Wants (2008) and Scarlet (2007), have begun to create inner depth for a character whose place in the filmed tradition also seems to be on the rise: Scarlet was played by Ray Winstone in the cult hit television series Robin of Sherwood (1984-86) and Christian Slater in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), and became a fan favorite (along with Allan a Dale) in the television series Robin Hood (2006-09). What follows is a brief description of Will Scarlet's characteristics and appearances during three major periods of the Robin Hood tradition's development: the earliest materials available, up to the middle of the seventeenth century, the stepping stone texts of the eighteenth through nineteenth centuries, and the advent of film and novels in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

EARLY

The first mention of Will Scarlet in the literary Robin Hood tradition is in the fifteenth century ballad Robin Hood and the Monk. In the ballad, Robin Hood decides to go to Nottingham, to pray in the church and hear Mass. The trip is against the counsel of Little John and Much, who advise Robin to take twelve outlaws with him; instead, Robin insultingly declares that Little John will carry his bow. The pair quarrel, and Robin departs for Nottingham alone, where he is recognized by a treacherous monk and captured by the Sheriff's forces. John and Much seek to free Robin from jail, ambushing the monk while he is on his way to report Robin's capture and bring back a warrant for his execution. The outlaws kill the monk and his young page, taking their places and obtaining the warrant, but when they approach Nottingham they find the gates barred. John asks why the gates are closed, and the porter replies that it is because Robin Hood is in the prison, and

John and Moch and Wyll Scathlok

For sothe as I yow say,

Thei slew oure men upon oure wallis,

And sawten us every day. (247-50)

Clearly, John and Much cannot have been assaulting the town on a daily basis, because they had traveled to obtain the warrant. The inclusion of "Wyll Scathlok" (Will Scathlock) in the list indicates that Will has some status in the Robin Hood tradition, though apparently he is less important than John or even Much. Possibly the third name is included for metrical reasons, but the early ballad tradition is not known for its metrical regularity or even the quality of its poetry. It seems more likely that Will Scathlock is mentioned because audiences would expect him to be included. In Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, Will appears fleetingly, for Little John returns to Barnsdale after (again) quarrelling with Robin, only to find two of his fellow outlaws slain,

And Scarlett a foote flyinge was,

Over stockes and stone,

For the sheriffe with seven score men

Fast after him is gone. (51-54)

Little John takes up his bow and covers Scarlett's retreat, but John is captured; Robin Hood will later return to rescue John, disguised in Guy's horsehide armor and bearing Guy's mutilated severed head. Scarlett does not reappear in the text.

Will also appears in the more extensive roll call of outlaws that begins the Gest of Robyn Hode, a ballad which first appears at the start of the sixteenth century though it is evidently of earlier composition. In the Gest, Will is the second named outlaw who stands with Robin, after Little John and preceding Much – an interesting change in order, since Will is third in Monk. Here, the poem claims that

Robyn stode in Bernesdale,

And lenyd hym to a tre,

And bi hym stode Litell Johnn,

A gode yeman was he.

And alsoo dyd gode Scarlok,

Much, the millers son:

There was non ynch of his bodi

But it was worth a grome. (9-16)

In this context, the ballad is providing a literary variation on the proverbial phrase "Robin Hood in Barnsdale stood." The phrase, which Thomas Ohlgren describes as "an opposing lawyer's characterization of another lawyer's pleading as irrelevant nonsense to which the opposing lawyer need not have responded," appears in legal cases and records as early as 1429 and as late as 1751 (19), and opens a sixteen-line poem on the royal household which Ohlgren dates to between 1452 and 1457 (20). The legal proverb later developed variations – "Robin Hood in Greenwood stood," and "Robin Hood in Barnwood stood," used in court cases through the early decades of the seventeenth century (Ohlgren 212 n14) – as well as literary variants like "Robin Hood in Sherwood stood," which first appears in Lincoln Cathedral MS 132, a manuscript dated to the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries (Ohlgren 18). The "gode Scarlok" appears to be a compromise, between Scathlock in Monk and Scarlett in Guy of Gisborne, and the character is apparently well known enough to the tradition that he no longer requires a personal name.

The significance of Scathlock / Scarlett as a surname presents an interesting historical perspective on the figure's repeated inclusion in the tradition. In their Dictionary of English Surnames, P. H. Reaney and R. M. Wilson present several examples of persons with the surname Scathlock, derived from Old English roots: Adam Scatheloc in 1315, Matilda Schathelok in 1359, and John Scathelok in 1402. Reaney and Wilson consider that the name means "Apparently 'burst the bars,' [from the] OE sceððan, loc. But the second element may be OE locc 'hair,' while the earliest example of the name, Ranulf Scathelac 1196 FFSr, would suggest OE lāc 'play, sport', perhaps in some such meaning as 'spoil-sport'" (394). However, Jan Jönsjö in Studies on Middle English Nicknames traces "Scauelock" to a different Old English root verb, "sc(e)afan," meaning "to shave," which he combines with "locc," or "hair," to signal that "[t]he name may refer to a barber or one who has a clean-shaven head," inviting comparison to the names "Schauwel" and "Shavenhead" (155). While Reaney, Wilson, and Jönsjö all agree that "lock" likely means "hair," the first half of the compound, "scath," is defined by the online Middle English Dictionary as a flexible term. Scath, or scathe, can alternately mean, "(a) Harm, injury; loss, damage; misfortune; danger; also, a harm, danger; to ~, to (a person's) harm or detriment; (b) harm or injury resulting from battle or war; defeat; (c) harm resulting from punishment; a punishment; (d) law. pl. monetary losses, damages; (e) physical defect; (f) reproach."

The Robin Hood tradition's gradual move towards the name Scarlet, as begun in Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, does not provide much further insight. Reaney notes in his Origin of English Surnames that many names often were connected to personal appearance, such as skin or hair color, citing the examples of the name "Burnell" in Chaucer. The situation is more complicated with "Scarlett" (or "Scarlet"), a word with Old French associations, because "Scarlett, OFr escarlate 'scarlet' can hardly have been used as a nickname for a scarlet face is too ephemeral for permanent description. It must be metonymic for a dealer in 'scarlet,' the name of a cloth already in 1182 (p), 'x ulnis de escarlato.' Other cloths, too, were named from their colour and when used as surnames must refer to makers or dealers" (246). He notes, however, that in "1363, a statute to restrict the dress of the peasantry ordered that all people not possessing 40 shillings' worth of goods and chattels were not to wear any manner of cloth but blanket and russet wool of twelvepence – cheap and too common to serve as a nickname distinctive of dress" (246).

In the modern tradition, Will Scarlet has become Robin Hood's cousin, usually when Robin is also a noble, but this elevation of Will's status has no foundation in the medieval literary tradition, though there is a single seventeenth-century ballad that makes this connection. This text, part of a seventeenth-century broadside collection, distinguishes Will Scathlock from Will Scarlet. It has a curious publication history: the ballad called Robin Hood and Will Scarlet in Stephen Knight and Thomas Ohlgren's 1997 collection of Robin Hood material was first published in the broadsides as Robin Hood Newly Revived, a name with no connection to the ballad's contents. The noted ballad scholar J. C. Child retained this title in his publications of the late nineteenth century, rejecting the title which Joseph Ritson provided in his 1795 work Robin Hood, a Collection of all the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads Now Extant Relating to that Celebrated English Outlaw. Knight and Ohlgren note that Ritson's title, Robin Hood and the Stranger, is an equally poor choice as Robin Hood Newly Revived since the latter "is itself a poor name as it has nothing to do with the content of the ballad and is basically a publicist's blurb" (499). They instead re-titled the ballad Robin Hood and Will Scarlet, to reflect the story's expansion of the outlaw band with a named member, and to fit more closely with the "Robin meets his match" tradition within which the ballad clearly participates. Here, the character is initially "Young Gamwell," and he claims that

"For the killing of my own fathers steward,

I am forc'd to this English wood,

And for to seek an uncle of mine;

Some call him Robin Hood" (70-74)

After he deals Robin a tremendous blow and reveals his parentage, the two embrace; though Little John offers to fight Young Gamwell, Robin refuses, saying

Oh, oh, no," quoth Robin Hood then,

"Little John, it may be so;

For he's my own dear sisters son,

And cousins I have no mo.

"But he shal be a bold yeoman of mine,

My chief man next to thee,

And I Robin Hood and thou Little John,

And Scarlet he shall be" (90-97)

The ballad is "relatively early and not too heavily marked as literary" but "unlike other seventeenth-century ballads, there are no other references to suggest that this story existed early, though the title Robin Hood Newly Revived might be taken to suggest that a previous text had been reshaped for publication" (Knight and Ohlgren 500).

Despite signs that Robin Hood and Will Scarlet, formerly Robin Hood Newly Revived, sought to incorporate an existing character into the tradition's patchwork mythos, a printing error in a Restoration era play indicates that not all seventeenth-century audiences accepted Will Scarlet as a member of Robin Hood's band. The work known as Robin Hood and His Crew of Souldiers was performed August 23, 1661, in Nottingham. This was the day of Charles II's coronation, and thus it is not surprising that the Robin Hood of this play "is a long way from the Robin who, while respecting the king, firmly resisted his authority" (Knight and Ohlgren 441). Robin and his men begin the play defiant of royal power. Will declares,

"Shall I change Venison for salt Cats, and make a bounteous meal, with the revision of a puddings skin? Or shall I bid adieu to Pheasant and Partrige, and such pleasing Cates, and perswade my hungry maw to satisfaction with the bruis of an Egge-shell? Or shall it be said that thou O famous Little John becomes the Attendant of a Tripe-woman?" (43-47).

Will is here scoffing at the notion, expressed by Little John, of the outlaws' willing "submission to government, and good Laws, as if we were the sons of peace and idleness, or had bin such Whay-blooded fools to live thus long honestly" (36-38): the "salt Cats" are delicacies, and the "bruis of an Egge-shell" indicates a sharp change in both the amount and type of food consumed. Despite these harsh words, the outlaws eventually accept the offered pardon "and with one voice sing, With hearty Wishes, health unto our King" (144-45). Notably, however, Robin Hood and his Crew of Souldiers demonstrates that Will Scathlock / Scarlet's membership in the outlaw band was not universally accepted by audiences. As Knight and Ohlgren observe, the printer of the play apparently erroneously split Will's part between two characters on the title page:

...the punctuation seems also to suggest that William and Scadlocke are two separate characters. This could be viewed as a punctuation error except that the title page lists, beneath Robin Hood, Commander, three names one beneath each other, all followed by a full stop: Little John. William. Scadlocke. . . . Apart from John and Robin, only the character named Will speaks, and it seems that this apparent confusion must arise from the fact that the printer did not know that William Scadlock was an outlaw's full name and treated it as two. (Knight and Ohlgren 450)

MIDDLE

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shaped the Robin Hood tradition, moving it away from the gleeful and sometimes pointless violence that often characterized the medieval and early modern material toward the more refined and thoughtful material that modern audiences currently enjoy. Many of these so-called stepping stone texts drew heavily on seventeenth century material, and a hard distinction between early and middle periods cannot be truly made. Rather, the texts that form the chronological middle of the Robin Hood tradition, particularly those which include Will Scarlet and are markedly distinct from the early material, frequently signal increasing refinement for both Robin and Will. Many more of those texts appeared in the nineteenth century than in the eighteenth; the eighteenth century saw, however, a significant rise in the popularity of ballads. Though Will Scarlet was still a minor character, his profile was raised by the many reprints of variant Robin Hood garlands, single ballad prints, and the rise in antiquarian research which culminated in Joseph Ritson's masterful 1795 collection of Robin Hood material.

The popularity of Robin Hood garlands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries contributed greatly to both an increase in Robin Hood material and also a surge in the tradition's vitality. Knight and Ohlgren observe that bound collections of Robin Hood ballads "became a standard item of the bookseller's trade" (453), and it is this popularity which has preserved many of the ballads. Printed cheaply for mass distribution, some ballads have survived only because the sheer number of circulating copies meant that the odds of at least one enduring were high. Though many of the so-called "later ballads" were created to meet this demand – and Robin Hood and Will Scarlet may well be one such product of the tradition's popularity – these

collections also do not contribute to the development of each figure's characteristics. Thus, Will Scarlet is still also Will Scathlock; despite the increasing popularity of Scarlet over Scathlock, Will is not often described, though he sometimes is dressed in his eponymous hue, and he is as anonymous as any named member of a dramatic chorus.

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw a surge of Robin Hood material. Leonard MacNally's 1789 Robin Hood; or, Sherwood Forest: A Comic Opera, of Three Acts seems to have heralded, in conjunction with Ritson's politically charged scholarly history of Robin Hood, a new level of seriousness in the tradition. MacNally's enduring historical legacy – which emerged only after his death in 1820 – was as a government spy for England against his fellow Irishmen, when he siphoned confidential information to the English even as he defended the Irish in the law courts. MacNally appears to have composed his play prior to commencing his activities as a double agent, which were said to have begun in 1793, at least four years after the play was performed. MacNally's work may not thus be consistently judged against his later actions, but his profession as a lawyer was prominently displayed on the title page of a 1789 edition of Robin Hood; or, Sherwood Forest. However, MacNally's then-future actions make his description of Will Scarlet, who is denounced by Allen a Dale to his sister Stella, richly ironic: Will is a man "[t]hat, in manners, he is a vain fop; and in his heart a cunning deceiver. Like an overripe pair, fair without, but bad within" (MacNally 13).

The antiquarian Ritson's politicization of the Robin Hood material is far more overt than the retroactive irony of MacNally. Ritson's introduction to his collection, a heavily annotated "Life of Robin Hood," clearly projects Ritson's own public sympathy for the nascent French Revolution. Ritson declares that in the forests, Robin Hood

for many years reigned like an independent sovereign; at perpetual war, indeed, with the king of England, and all his subjects, with an exception, however, of the poor and needy, and such were 'desolate and oppressed,' or stood in need of his protection. When molested, by a superior force, in one place, he retired to another, still defying the power of what was called law and government, and making his enemies pay dearly, as well for their open attacks, as for their clandestine treachery. It is not, at the same time, to be concluded that he must, in this opposition, have been guilty of manifest treason or rebellion; as he most certainly can be justly charged with neither. An outlaw, in those times, being deprived of protection, owed no allegiance: 'his hand "was" against every man, and every mans hand against him'. These forests, in short, were his territories; those who accompanied and adhered to him his subjects. (viii)

Ritson's assessment of medieval law is dubious and largely incorrect, heavily tainted with ideology, but these sentiments are familiar to modern audiences to whom government is represented in the (highly fictional) "bad" prince John and "good" king Richard. Ritson's perspective certainly influenced John Keats's poem "Robin Hood: to a Friend," composed in 1818 (published 1820), in which Keats used the winter of the modern era as a harsh contrast to the warm summer and general pastoral liberty of Robin's golden age greenwood.

The early decades of the nineteenth century saw a major increase in original Robin Hood material, but Will Scarlet appears in very little of it. He is absent from Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe (1819) and from the poetry exchange between John Hamilton Reynolds and John Keats in 1818 and 1819. Thomas Love Peacock does utilize the character in Maid Marian (1822), where Scarlet is born Young Gamwell, cousin to Robert Fitz-Ooth, Earl of Locksley and Huntingdon, but must be rescued from the sheriff's gallows for a life in the greenwood. There, "Young Gamwell, taking it for granted that his offence was past remission, determined on joining Robin Hood, and accompanied him to the forest, where it was deemed expedient that he should change his name; and he was rechristened without a priest, and with wine instead of water, by the immortal name of Scarlet" (82). But this is the extent of Scarlet's development: he appears occasionally, but no major plots or narrative cruces hang upon his shoulders. Nor does Leigh Hunt utilize Scarlet in three of his four Robin Hood poems, first published in the literary newspaper The Indicator in 1820. Scarlet does appear in a fourth poem, "Robin Hood's Flight," where he is a poor and starving man, collecting branches in Gamelyn Wood. Robin kills a deer and gives him a large portion,

And Scarlet took and half roasted it,

Blubbering with blinding tears,

And ere he had eaten a second bit,

A trampling came to their ears. (80-83)

In gratitude for the food and kindness, Will confesses to killing the deer, but Robin will not permit him to be arrested. After killing the men who attack them, Robin and Will decide to travel with the one forester who did not join the assault. Instead, he stood aside and begged Robin's pardon, and says

And I pray thee let me follow thee

Any where under the sky,

For thou wilt never stay here with me,

Nor without thee can I. (125-28)

The unnamed forester, Will, and Robin take a last lingering look at Locksley town, and then march off, Robin flanked by his companions.

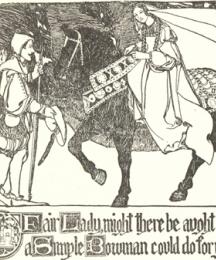

The other notable Robin Hood texts of the nineteenth century, Howard Pyle's The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883) and Reginald De Koven's light comic opera Robin Hood (1888-89), both include appearances by Will Scarlet. Pyle's Scarlet is initially presented as a dandy, strolling lightly down a forest road. His illustration of Will and Robin's meeting, "Merry Robin Stops a Stranger in Scarlet," features Robin standing stoutly with his back to the viewer, and settling the focus of the picture on the contrasts: between Robin's plain attire and Will's elaborate draping sleeves; Robin's set posture and Will's posing S-curve stance; and finally Robin's firm grip on a quarter-staff and Will's delicate sniffing of a flowering rose. Robin declares that "the sight of such a fellow doth put a nasty taste into my mouth! . . . What a pity that such men as he, that have no thought but to go abroad in gay clothes, should have good fellows, whose shoes they are not fit to tie, dancing at their bidding" (75) and determines that he will challenge the stranger to demonstrate how "woodland life toughens a man, as easy living, such as thine hath been of late, drags him down" (76). The stranger demonstrates prodigious strength, tearing a tree up by its roots to make himself a quarter-staff, and eventually knocks Robin to the road. He calls himself Will Gamwell, and Robin realizes that his foe is none other than his sister's son. Will's story is drawn largely from Robin Hood and Will Scarlet, with elements similar to Peacock's Maid Marian novel. Robin invites Will to join the band, and "so, because of thy gay clothes, thou shalt henceforth and for aye be called Will Scarlet" (80). For De Koven, Will Scarlet is a blacksmith and armorer, and his vocal part is bass – a very different perspective than the one Pyle presented just a few years prior.

MODERN

The modern Will Scarlet began the twentieth century as one of the named Merry Men – but, aside from Little John, he rarely featured prominently in a film or play. In the 1922 film Robin Hood Maine Geary (later Bud Geary) played Will Scarlet, and the role was largely background, with a few featured moments of greenwood play, designed to show off Fairbanks's athletics. The 1938 film The Adventures of Robin Hood, one of the first major Hollywood productions to be filmed in expensive Technicolor, opens as Robin Hood (Errol Flynn) and Will Scarlet (Patrick Knowles) ride through the forest together. They encounter Much, a peasant poacher, enduring harassment by Sir Guy of Gisborne; Will encourages Robin to rescue Much. When Robin provokes Prince John into declaring him an outlaw, Will and Robin escape to Sherwood Forest together, where they meet Little John and Friar Tuck, and form a massive outlaw army and brotherhood. The Will Scarlet of the Flynn film is clearly based on the Pyle illustrations. Though he is not quite so much a dandy as Pyle's Scarlet, Patrick Knowles's Will Scarlet enjoys music and frequently strums a lute, a role reminiscent of Alan a Dale.

The Flynn Technicolor epic has influenced every Robin Hood production since 1938, to the point that productions will either mimic its visual presentations closely, as was done by the 1950s television show, 1994 film Robin Hood: Men in Tights, and 1997-99 television series The New Adventures of Robin Hood, or seek to depart from them completely, as accomplished by the mid-1980s Robin of Sherwood, 1991's Robin Hood and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, and the 2010 Robin Hood starring Russell Crowe. The characterization of Will Scarlet, however, developed quickly in the 1980s and 1990s, through the contrasting performances of Ray Winstone and Christian Slater in Robin of Sherwood and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, respectively. Winston's Will Scathlock is driven mad with grief when his wife is raped and murdered by the Sheriff's men; he slaughters them all in revenge, and his outlaw nom de guerre comes from the color of the blood he spilt in such quantity. Slater's Will Scarlet is the illegitimate half-brother of Kevin Costner's Robin Hood. No attempt is made to explain his name, and Slater's Scarlet is hot-tempered, impetuous, and resentful of Robin, who is heir to their father's estates and affections despite his long absence from England on Crusade. Recent versions of Will Scarlet include Harry Lloyd's quiet carpenter (Robin Hood, TV, 2006-2007) and Scott Grimes's redheaded outlaw (Robin Hood, film, 2010).

The Flynn film has also influenced novels. Diane Carey's Under the Wild Moon (1986) directly acknowledges its debt to Knowles's Scarlet and Flynn's Robin. Strong characterizations of Will Scarlet, largely drawn from Pyle and the early cinema tradition, mark novels like Robin McKinley's The Outlaws of Sherwood (1989). Indeed, a depiction of an adult and noble Will Scarlet usually displays characteristics from those sources. But the appeal of a tougher and rougher Will Scarlet, with his name signaling either blood or passion, has been growing in popularity since Winston's performance in the 1980s. Jennifer Roberson's Lady of the Forest (1993) is perhaps the first mainstream Robin Hood novel to feature a brutal and rough Will. As Robin Hood films have increasing focused on "historical" costuming choices, the red-clad dandy of Pyle and the Flynn film rarely appears. Certainly Stephen Lawhead's Scarlet (2007) features just such a low-class and rough Will, though there are works which seek to combine the two increasingly divergent traditions. Carrie Lofty's What a Scoundrel Wants (2007) is one such novel: this Will Scarlet is Robin Hood's nephew, both looking up to and resenting his uncle, and constantly comparing himself to a figure that he has begun to idealize: "His pride shriveled like an apple left in the sun. Shortcomings dogged his every step, especially when faced with men who yet compared him to Robin. He needed no such reminders" (56). This Scarlet's name is derived from the two scarlet lions he wears on his tunic. Lofty's novel also utilizes, as chapter headings, excerpts and quotations from nearly every appearance of Will Scarlet throughout the Robin Hood tradition's long history.

In the twenty-first century, the modern Will Scarlet has moved toward depth and motivations that are not present in most of the earlier material. This has offered filmmakers, novelists, comic book artists, and poets unprecedented license with a character that is as old as Robin Hood, if not as well known. There are few limitations on the character, and though the focus of a Robin Hood film, novel, television series, or other media production, will always be first on Robin (and perhaps now also Marian), Will Scarlet has begun to eclipse his fellow merry men. While he cannot replace Little John as Robin's right hand, the character is steadily being cemented as Robin's reliable left hand, a man who will do what John and Robin cannot (or will not), and a figure worthy of future development.

Bibliography

Early

Robin Hood and the Monk (c. 1450).

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (c. 1475-1500).

A Gest of Robyn Hode (c. 1500).

Robin Hood and his Crew of Souldiers (1661).

Robin Hood and Will Scarlet, formerly Robin Hood Newly Revised (17th century).

Middle

Leonard MacNally, Robin Hood; or, Sherwood Forest: A Comic Opera, of Three Acts (1789).

Joseph Ritson, Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to that Celebrated English Outlaw (1795).

Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire (1883).

Reginald De Kovan, Robin Hood (1890).

Modern

Robin Hood (1922). Dir. Allan Dwan. Perf. Douglas Fairbanks (Robin Hood), Maine Geary (Will Scarlet).

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Dir. Michael Curtiz and William Keighley. Perf. Errol Flynn (Robin Hood), Patrick Knowles (Will Scarlet).

Diane Carey, Under the Wild Moon (1986).

Robin McKinley, The Outlaws of Sherwood (1989).

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991). Dir. Kevin Reynolds. Perf. Kevin Costner (Robin Hood), Christian Slater (Will Scarlet).

Robin Hood (1991). Dir. John Irvin. Perf. Patrick Bergin (Robin Hood), Owen Teale (Will Scarlet).

Robin of Sherwood. Dir. Ian Sharp. Perf. Michael Praed (Robin Hood), Ray Winstone (Will Scarlet). HTV (1984-86).

Jennifer Roberson, Lady of the Forest (1993).

Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993). Dir. Mel Brooks. Perf. Cary Elwes (Robin Hood), Matthew Porretta (Will Scarlet O'Hara).

Ed Pahnke, Northern Knights (2004).

Robin Hood. Perf. Jonas Armstrong (Robin Hood), Harry Lloyd (Will Scarlet). Tiger Aspect BBC (2006-09).

Caroline Linden, What a Rogue Desires (2007).

Stephen Lawhead, Scarlet (2007).

Carrie Lofty, What a Scoundrel Wants (2008)

Robin Hood (2010). Dir. Ridley Scott. Perf. Russell Crowe (Robin Hood), Scott Grimes (Will Scarlet).

Works Cited

De Koven, Reginald and Harry B. Smith.

Robin Hood: A Comic Opera in Three Acts. New York: Burr Printing House, 1896.

Hunt, Leigh. "Robin Hood's Flight."

The Indicator (15 Nov. 1820): 44-47.

Jönsjö, Jan.

Studies on Middle English Nicknames: Volume 1: Compounds. Lund: CWK Gleerup, 1979.

Knight, Stephen T. and Thomas H. Ohlgren, eds.

Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

MacNally, Leonard.

Robin Hood; or, Sherwood Forest: A Comic Opera, of Three Acts. London: Printed for W. Lowndes, 1789.

Ohlgren, Thomas H.

Robin Hood: The Early Poems, 1465-1560: Texts, Contexts, and Ideology. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007.

Peacock, Thomas Love.

Maid Marian. 1822. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Library, 1997. eBook.

Pyle, Howard.

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire. 1883. New York: Scribner Sons, 1946.

Reaney, P. H.

The Origin of English Surnames. 1967. London: Routledge and K. Paul, 1969.

Reaney, P. H. and R. M. Wilson.

A Dictionary of English Surnames. Rev. 3

rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Ritson, Joseph.

Robin Hood: A Collection of all the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to that Celebrated English Outlaw. 1795. London: W. Pickering, 1832.

Read Less