Read Less

And so ever after, as long as he liv'd,

Although he was proper and tall,

Yet nevertheless, the truth to express,

Still Little John they did him call.

—Robin Hood and Little John (c. 1680-85, l. 154-7)

Critical and literary attention has rarely deflected from Robin Hood to land upon Little John, despite the character's prominence in the early modern / late medieval tradition. There is a curious split within the early materials of the Robin Hood tradition: three of the four Scottish chronicles which include Robin Hood mention John as well, and John appears prominently in the four earliest surviving ballads, the texts which are the foundation of the literary Robin Hood; however, references to Little John are far rarer in the popular proverb tradition, as well as in the brief chronicle references to the tradition from within a larger cultural context. The division continues today—where modern audiences find Robin Hood, Little John is never be far behind, yet he remains a member of the supporting cast, and is seldom found in the spotlight himself.

As with Robin Hood, the materials of Little John's mythic biography are scattered across several hundred years; unlike Robin Hood, there is no critical study devoted to Little John. As Stephen Knight notes, "[i]n the Robin Hood tradition the major characters do not change positions, moods and personalities" (Knight 3), though the circumstances they encounter are extremely flexible. This lack of change, combined with a general tendency to emphasize Robin's adventures over John's, has contributed to the absence of critical studies on Little John. What follows is a brief analysis of Little John's characteristics during three major periods of the legend's development: the medieval / early modern ballads and chronicles, the stepping stone texts of the late sixteenth through nineteenth centuries), and the advent of film and novels in twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

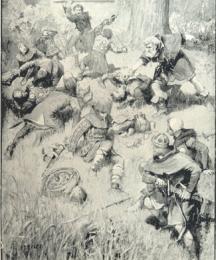

EARLY

The early ballad tradition consists of four texts: Robin Hood and the Monk, Robin Hood and the Potter, A Gest of Robyn Hode, and Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne. The dating of these four texts is uncertain and under continual revision; nevertheless, all appear to have been in circulation by the early years of the 16th century, and were firmly established before 1600. Little John appears prominently in all four. In Monk, particularly, John is far more heroic and central to the poem than its titular hero, and the plot focuses on John's efforts to free Robin from the Sheriff's prison. John is not without flaws that present contemporary audiences with a serious moral dilemma: as part of his plan to free Robin, John stalks, entraps, murders, and steals the identity of the monk who betrayed Robin to the Sheriff. John and Much travel to meet the King in the monk's place and deliberately deceive him in order to gain access to documents stamped with the royal seal; they then use these official documents to gain entry to fortified Nottingham and to free Robin Hood. Arguably, John's actions reflect Robin Hood's own attitudes—Robin is not a pleasant personality in this story—and Robin appears to acknowledge this codependency when he offers John leadership of the outlaw band. In A Gest, John is a major player, prompting Robin to greater charity for the poor knight and engaging in an independent adventure. In Guy, the ballad's focus is split between John and Robin, though the emphasis remains upon Robin: each outlaw has his own adventure, and they are reunited when Robin, disguised as Guy, rescues John from the Sheriff's clutches. John plays a minor role in Potter, despite an appearance in the opening lines. Interestingly, though critics frequently notice the traditional lyrical greenwood opening which appears in three of the four early ballads (missing only from A Gest), John's presence in the opening of all four ballads generally goes unexamined.

The early ballad tradition consists of four texts: Robin Hood and the Monk, Robin Hood and the Potter, A Gest of Robyn Hode, and Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne. The dating of these four texts is uncertain and under continual revision; nevertheless, all appear to have been in circulation by the early years of the 16th century, and were firmly established before 1600. Little John appears prominently in all four. In Monk, particularly, John is far more heroic and central to the poem than its titular hero, and the plot focuses on John's efforts to free Robin from the Sheriff's prison. John is not without flaws that present contemporary audiences with a serious moral dilemma: as part of his plan to free Robin, John stalks, entraps, murders, and steals the identity of the monk who betrayed Robin to the Sheriff. John and Much travel to meet the King in the monk's place and deliberately deceive him in order to gain access to documents stamped with the royal seal; they then use these official documents to gain entry to fortified Nottingham and to free Robin Hood. Arguably, John's actions reflect Robin Hood's own attitudes—Robin is not a pleasant personality in this story—and Robin appears to acknowledge this codependency when he offers John leadership of the outlaw band. In A Gest, John is a major player, prompting Robin to greater charity for the poor knight and engaging in an independent adventure. In Guy, the ballad's focus is split between John and Robin, though the emphasis remains upon Robin: each outlaw has his own adventure, and they are reunited when Robin, disguised as Guy, rescues John from the Sheriff's clutches. John plays a minor role in Potter, despite an appearance in the opening lines. Interestingly, though critics frequently notice the traditional lyrical greenwood opening which appears in three of the four early ballads (missing only from A Gest), John's presence in the opening of all four ballads generally goes unexamined.

Little John also features prominently within the Scottish chronicle tradition. Three of the four medieval chronicles which devote space to Robin Hood also mention John. Andrew of Wyntoun's Orygynale Chronicle (c. 1420) offers four lines on the famous outlaws under the year 1283:

Litil Iohun and Robert Hude

Waythmen war commendit gud;

In Ingilwode and Bernnysdaile

Thai oyssit al this tyme thar trawale.

(Knight and Ohlgren 24) |

Forest outlaws; praised

practiced; labor

|

Walter Bower's continuation of John of Fordun's Scotichronicon (c. 1440) also mentions John; as Knight and Ohlgren note, Bower calls Robin Hood a "famosus siccarius (a well-known cutthroat), a more severe account than Wyntoun's waythmen who were commendit gud" (Knight and Ohlgren 25). Bower also changes the historical context of the entry: Wyntoun inserts John and Robin under 1283 during the Scottish wars of Edward I, yet Bower moved the date to 1266 during Simon de Montfort's rebellion against Henry III. Bower's account also emphasizes the popular nature of the stories:

Then arose the famous murderer Robin Hood, as well as Little John, together with their accomplices from among the disinherited, whom the foolish populace are so inordinately fond of celebrating both in tragedies and comedies, and about whom they are delighted to hear the jesters and minstrels sing above all other ballads.

(trans. A. I. Jones; qtd. Knight and Ohlgren 26)

Bower and Wyntoun were not the only Scottish chroniclers to include mention of Little John in their descriptions of Robin Hood. A generation later, the Latin history by John Major (Mair), Historia Majoris Britanniae (1521; likely written c. 1500), relocated the stories of Robin Hood and Little John to the last years of the twelfth century and the reign of King John, a context familiar to modern audiences. Knight and Ohlgren observe that "[t]his is the first time that the outlaw is linked with the period of King Richard. In later hands this was to re-shape Robin's resistance to authority itself as an act of a noble conservatism, since bad King John could be attacked and true kingship defended at the same time" (Knight and Ohlgren 27). Major's contributions to the modern perception of Robin Hood and Little John are not limited to shifting the setting of the stories to the pre-Magna Carta period. Major's account of the outlaws is uniformly positive, as he claims that

[a]bout this time it was, as I conceive, that there flourished those most famous robbers Robert Hood, an Englishman, and Little John, who lay in wait in the woods, but spoiled of their goods those only that were wealthy. They took the life of no man, unless he either attacked them or offered resistance in the defence of his property.

(qtd. Knight and Ohlgren 27)

Major's reinterpretation of the legend is very familiar to modern audiences of the Robin Hood materials, offering the first explicit account of the outlaws as social reformists who took from the rich to give to the poor. Critics agree that Major was surely familiar with A Gest of Robyn Hode, which was in wide circulation by 1500, and, as in all the surviving early ballads, Little John's role in A Gest was substantial.

Exactly why Major chose to relocate the traditional setting is unknown; if he was following a source, whether historical or literary, that has been lost. Knight and Ohlgren speculate that Major's changes occurred under the influence of the romance Fouke le Fitz Waryn (c. 1325-40), which is set during the reign of John. Of the four surviving early ballads, only A Gest provides a name for the king, but that name is "Edward," and the first of the Plantagenet kings named Edward was not born until 1239; the succession of Edward I, II, and III continued until 1377. Major's successors did not follow his example when placing Robin Hood or Little John in a historical period. Rather, the printed editions of John Bellenden's Chronicles of Scotland (circa 1536-40) followed Bower's example and placed Robin Hood and Little John in the context of the de Montefort rebellion. Bellenden claims that "[a]bout this time [1266] was the waithman, Robert Hode, with his fallow, Litil Johne; of quhom ar mony fabillis and mery sportis soung amang the vulgar pepill" (Bellenden 1821 edition [Bk. 13 ch. 19], 354). Bellenden's use of the term "waithman" to describe Little John and Robin Hood is significant; the word denotes "a hunter; esp. applied to forest outlaws" (MED), thus locating John and Robin firmly in the context of woodlands and hunting, and linking Bellenden's texts to Andrew of Wyntoun's own use of the term.

However, Bellenden's Chronicles of Scotland survives, as Nicola Royan notes, "in two discrete forms" (136), manuscript and print; the manuscript tradition shows evidence of multiple reworkings and revisions, and the printed text, which is markedly different from the manuscripts, appears to have been produced later, appearing between 1536 and 1540 (Royan 137). The text of circa 1536-40, printed by Thomas Davidson in Edinburgh, adds the aforementioned Robin Hood reference at the end of Book 13, chapter 19, which appears to be Bellenden's own addition. The printed text also includes a translation of Hector Boece's "Scotorum Regni Descriptio," claiming in chapter 8 that "[i]n Murray land is the kick of Pette, quhare the banis of lytill Iohne remanis in gret admiratioun of pepill. He hes bene fourtene fut of hycht with square membris effering thairto .vi. yeris afore the cumyng of this werk to lycht we saw his hanche bane als mekill as the haill bane of ane man" ["In Murray land is the church of Pette, where the bones of Little John remain in great admiration of people. Six years before the coming of this work to light we saw his hip bone thus as big as the whole bone of any man"] (“Cosmographe and Discription of Albion," Ch. viii). Little John's bones, in this account, are the object of great veneration and admiration, both for their remarkably enormous size and (presumably) for his own fame. Unlike the reference to Robin Hood and Little John as "waithmen," the passage is a translation by Bellenden of the matching passage in Boece's Latin Scotorum historiæ a prima gentis origine (1527). Boece's inclusion of the reference to Little John is notable because Boece wrote for a highly-educated Continental audience, while Bellenden wrote for a moderately-educated Scottish audience which evidently required translation from Latin; Boece's audience presumably had less interest in Little John than Bellenden's. In 1795 the passage describing John's bones was cited by the antiquarian Joseph Ritson in his landmark Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw, and attributed solely to Hector Boece. For over two centuries, scholars have followed Ritson's lead and inaccurately cited Boece when quoting Bellenden's Middle Scots text. Though Boece's Scotorum historiæ (1527; reprinted 1574) was the basis of Bellenden's Chronicles of Scotland, Boece's text does not include the reference to Robin and John in the context of the de Montefort rebellion of 1266. The addition is attributable to Bellenden, whose work(s), even by early modern standards, cannot truly be called "translations." The relationship of Bellenden to Boece's works is vexed, and referring to Bellenden's works with Boece's name is inaccurate. Though most scholars do make this error, Nicola Royan notes that "[w]hen a translator breaks from his original in his rendition of the very title, it does not bode well for the accuracy of the rest" (139). Indeed, Bellenden's interpretations of Boece's Scotorum historiæ, particularly the printed text which may have been revised from earlier manuscripts jointly by Boece and Bellenden (Mapstone 165), are by modern standards less translations than free re-writings. However, the Robin Hood materials are known for their flexibility, and were (and still are) continually re-written to meet the changing needs of the audience, traits which are certainly evident in the variation which the Bellenden texts provide.

MIDDLE

As Robin Hood developed aristocratic characteristics, Little John's role as his partner and co-leader of the outlaw band diminished. Despite the equality presented in the Scottish chronicle tradition, Richard Grafton's influential and popular 1569 Chronicle at Large—appearing a mere two decades after Bellenden's printed text—makes no mention of Little John, and "firmly gentrified" Robin Hood himself (Knight and Ohlgren 27). John's status continued to decline, and by the close of the 16th century, the literary tradition had virtually eliminated Robin and John's equality, as is particularly notable in Anthony Munday's plays (1598 and 1599) where John appeared as Robin's servant.

There were few exceptions to John's decline in social rank. J. C. Holt notes that prominent seventeenth-century antiquarian Roger Dodsworth left "miscellaneous jottings" which indicate the odd position Little John holds in the Robin Hood tradition: in notes on Robin's biography, Dodsworth wrote that after fatally wounding his stepfather, Robin Hood then "came to Clifton upon Calder, and came acquainted with Little John, that kept the kine; which said John is buried at Hathershead in Derbyshire, where he hath a fair tomb-stone with an inscription. Mr Long saith that Fabyan saith, Little John was an earl Huntingdon" (Holt 44). Dodsworth's notes provide a unique view of Little John, though the story of an outlawed earl of Huntingdon is a familiar component of Robin's biography and not John's own. Here, John is both Little John and the earl of Huntingdon; yet "Little John" would be a distinctly odd name for a peer of the realm. From servant to earl is a large step indeed, and given that whenever Robin Hood is cast in the role of earl his name is changed to "Robert," indicating the shift in social status, it seems distinctly odd that John would remain "Little John" in an identical situation. Though Holt dismisses the account quickly, Knight contends that "this story also seems to have strong Derbyshire and Little John influence" and also that "the notion that John held the earldom … is unique to these notes: Fabian, a sixteenth-century chronicler, does not in fact say that Little John held the Huntingdon title" (Knight 19). Dodsworth's notes are thus immediately suspect upon first reading. Nevertheless, a "quite different version of the Robin Hood myth is shadowed behind Dodsworth's notes, with an unusual motivation for outlawry and no real sense that Robin was a leader. But that popular and flexible Robin is largely lost in the treatments of other antiquarians, because their mode tends towards a uniform and historicized identity for the hero" (Knight 19). Dodsworth's notes may reflect the contradictions of the tradition or simply be random scribbling; however, the fluidity of leadership within the outlaw band, detected by Knight, is accurate in the context of the early ballad tradition. Equally important is the emphasis Knight places upon the "popular and flexible Robin," an adaptability which holds true for Little John as well.

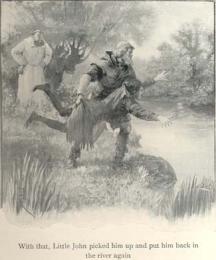

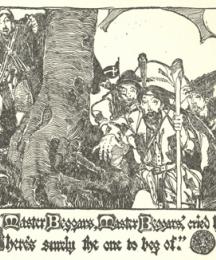

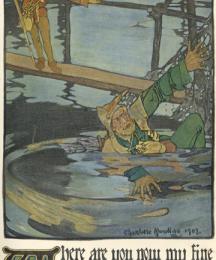

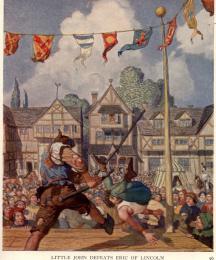

John's role as loyal sidekick continued in the later ballads of the seventeenth century. These later ballads are notable for their commercial nature as the products of widespread, and evidently profitable, broadsheet printing runs; they also contribute many of the details which modern audiences recognize and identify as central to the Robin Hood legends. Little John's back story is part of the trend, appearing in Robin Hood and Little John, a ballad which the preeminent nineteenth-century literary scholar Francis James Child declared had "a rank seventeenth century style" (qtd. Knight and Ohlgren 476), but is none the less a "classic 'Robin Hood meets his match' ballad [which] still outlines a focus of solidarity and tricksterism, presenting a central event in the myth which has remained dear, even obsessive, in the hearts of theatrical and film redactors over the centuries" (Knight and Ohlgren 477). The episode includes the famous staff fight on a small bridge ("Now here on the bridge we will play; / Whoever falls in, the other shall win / The battle, and so we'll away," l. 51-3), which Robin loses (l. 76-77), as well as the re-naming of John Little to Little John ("The words we'll transpose, so where-ever he goes, / His name shall be call'd Little John," l. 132-3). Notably, it is William Stutely, and not Robin Hood, who renames John and serves as his "godfather" (l. 115). Knight and Ohlgren note that the ballad text can be traced to between 1680 to 1685, though earlier versions—plays and ballads alike—may have been more general in nature, since this ballad appears to have been professionally produced as a "prequel" to long-standing stories like A Gest of Robyn Hode (Knight and Ohlgren 476).

Notably, it is William Stutely, and not Robin Hood, who renames John and serves as his "godfather" (l. 115). Knight and Ohlgren note that the ballad text can be traced to between 1680 to 1685, though earlier versions—plays and ballads alike—may have been more general in nature, since this ballad appears to have been professionally produced as a "prequel" to long-standing stories like A Gest of Robyn Hode (Knight and Ohlgren 476).

Interest in the Robin Hood stories tends to be cyclical, strongly linked to periods of political and cultural change; it is no surprise that Joseph Ritson's collection appeared in the midst of the French Revolution, and the sudden flurry of Robin Hood materials around the years 1818-19 may be linked to issues ranging from censorship to the cultural impact of the Industrial Revolution. J. R. R. Reynolds, John Keats, Thomas Love Peacock, and Sir Walter Scott—to name only the most prominent participants in this surge—all produced poems or novels in which Robin Hood appeared. Keats' sharp response to Reynolds' rather idyllic Robin Hood poems invokes John and Robin together in the same line, "But you never may behold / Little John, or Robin bold" (l. 23-4), as representative figures of the idealized past which will never again appear in the modern world. Keats' poem is remarkable for its hopelessness: Robin and John had until this point generally been invoked as semi-historicized exemplars or metonyms for a past which may reappear in the present, ushering in a modern golden age. It is Scott's Ivanhoe, however, which serves as a true bridge between the seventeenth-century ballads and the twentieth-century films and novels of Robin Hood. Notably, though Little John is absent from the story and the two outlaws who serve as the public face of the greenwood band are Locksley (Robin Hood) and the friar, Scott clearly felt the need to justify John's absence to his audience. In the long discussion between Robin and King Richard, the king asks "'Tell me, bold Robin, hast thou never a friend in thy band, who, not content with advising, will needs direct thy motions, and look miserable when thou dost presume to act for thyself?'" Robin's response is telling, and informative: "'Such a one,' said Robin, 'is my Lieutenant, Little John, who is even now absent on an expedition as far as the borders of Scotland; and I will own to your Majesty, that I am sometimes displeased by the freedom of his councils— but, when I think twice, I cannot be long angry with one who can have no motive for his anxiety save zeal for his master's service'" (ch. 41). John's position as Robin's right-hand man, a lieutenant to Robin's captain, and as advisor trusted to speak his mind even when the truth might be hard to hear, is firmly solidified, and his absence is justified by Robin's trust.

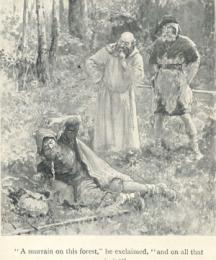

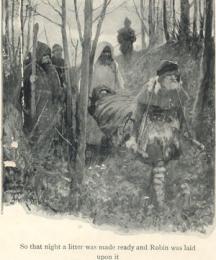

Howard Pyle's The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire (1883) further solidified John's position as an affable and dependable lieutenant to the more flighty and adventuresome Robin. Pyle's work, which was repeatedly reprinted during his lifetime and continues to be one of the definitive modern retellings of the Robin Hood myths, also provided the visual template for John's character: tall, dark, and bearded, with a staff in one hand and a generally solemn expression to offset Robin's laughter.

MODERN

The modern era of Robin Hood materials, and thus of John as well, owes a substantial debt to Pyle's illustrations in The Merry Adventures. Alan Hale's casting as Little John in the two major films of the modern tradition—the production starring Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., in 1922 and that starring Errol Flynn in 1938— as well as a more obscure third film, Rogues of Sherwood Forest in 1950, cemented the character's general standing in filmed versions of the legend, despite the differences in Hale's performances from production to production. Physically, John has had more consistency than Robin: he is nearly always tall, usually dark-haired and bearded—though he has been blond and clean shaven, he is usually a physical contrast to Robin—and is nearly always the voice of reason. Consequently, he is often portrayed as being older than Robin and often serves as a paternal stand-in, either for Robin or, as with Hale's final turn in the role, to Robin's own child. In the last thirty years, particularly in filmed productions—whether for cinema or television—John's character has been portrayed as tall, bearded, with dark curly hair and a slightly sub-par intellect but superior empathetic capabilities, generally a father and family man; in sum, a tamed wild man. Laura Blunk identifies 1975-76 as the pivotal years for this reworking of Little John's character, with his appearences in the BBC miniseries The Legend of Robin Hood (1975) and Robin and Marian (1976) as models which all later filmed versions of the character draw upon (Blunk 209). Clive Mantle (Robin of Sherwood, 1984-86), David Morrissey (Robin Hood, 1991), Nick Brimble (Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, 1991), and Gordon Kennedy (Robin Hood, 2006-2008) have all played the character in this mode. Deviations from the model include blonds Eric Allan Kramer (Robin Hood: Men in Tights, 1993) and Richard Ashton (The New Adventures of Robin Hood, 1996-98). Written texts have taken their cues from their filmed counterparts, and though various novelists present John as alternately complex, simple, or a good man caught up in bad circumstances, his characterization in fiction is not significantly different from that found in the filmed tradition.

The modern era of Robin Hood materials, and thus of John as well, owes a substantial debt to Pyle's illustrations in The Merry Adventures. Alan Hale's casting as Little John in the two major films of the modern tradition—the production starring Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., in 1922 and that starring Errol Flynn in 1938— as well as a more obscure third film, Rogues of Sherwood Forest in 1950, cemented the character's general standing in filmed versions of the legend, despite the differences in Hale's performances from production to production. Physically, John has had more consistency than Robin: he is nearly always tall, usually dark-haired and bearded—though he has been blond and clean shaven, he is usually a physical contrast to Robin—and is nearly always the voice of reason. Consequently, he is often portrayed as being older than Robin and often serves as a paternal stand-in, either for Robin or, as with Hale's final turn in the role, to Robin's own child. In the last thirty years, particularly in filmed productions—whether for cinema or television—John's character has been portrayed as tall, bearded, with dark curly hair and a slightly sub-par intellect but superior empathetic capabilities, generally a father and family man; in sum, a tamed wild man. Laura Blunk identifies 1975-76 as the pivotal years for this reworking of Little John's character, with his appearences in the BBC miniseries The Legend of Robin Hood (1975) and Robin and Marian (1976) as models which all later filmed versions of the character draw upon (Blunk 209). Clive Mantle (Robin of Sherwood, 1984-86), David Morrissey (Robin Hood, 1991), Nick Brimble (Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, 1991), and Gordon Kennedy (Robin Hood, 2006-2008) have all played the character in this mode. Deviations from the model include blonds Eric Allan Kramer (Robin Hood: Men in Tights, 1993) and Richard Ashton (The New Adventures of Robin Hood, 1996-98). Written texts have taken their cues from their filmed counterparts, and though various novelists present John as alternately complex, simple, or a good man caught up in bad circumstances, his characterization in fiction is not significantly different from that found in the filmed tradition.

That Little John's characterization is easily reducible to physical traits is not surprising. The marginalization of the character in favor of Robin Hood's development seems to have forced John to become what Robin Hood is not, a figure defined as much by his physicality as by his character traits. Little John appears to appeal on a more personal level than Robin Hood, perhaps explaining the physical consistency of his portrayals. John's position as the steady second to Robin's idealism, or as man to Robin's boy, or as body to Robin's intellect, reflects the arc of the character from his first appearance as Robin's co-equal leader of a band of medieval outlaws to his position as a vital subordinate needed to balance the very qualities which make Robin his superior.

Though Little John is not as widely represented in popular culture as Robin Hood, the figure has always been a significant force in the literary tradition. The following is a fragmentary list of works significant in the development of the Little John character; this list is intended to provide a representative range of material rather than an exhaustive bibliography.

Bibliography

Early

Robin Hood and the Monk (late fifteenth century).

Robin Hood and the Potter (c. 1500).

A Gest of Robyn Hode (early sixteenth century).

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (early sixteenth century).

Andrew of Wyntoun, Orygynale Chronicle (c. 1420).

John of Fordun, Walter Bower, Scotichronicon (c. 1440).

John Major, Historia Majoris Britanniae (1521).

John Bellenden, Chronicles of Scotland (manuscript 1533; printed 1540).

Middle

Anthoy Munday, The Downfall of Robert Earle of Huntington (1598), The Death of Robert Earle of Huntington (1599).

Robin Hood and Little John (c. 1624).

Martin Parker, A True Tale of Robin Hood (1632).

Little John a Begging (1640-1663).

Robin Hood and His Crew of Souldiers (1661).

Sir Walter Scott, Ivanhoe (1818), chapter 41.

J. R. Reynolds, "Sonnet on Robin Hood I," "Sonnet on Robin Hood II" (1819).

John Keats, "Robin Hood, to a Friend" (1820).

Pierce Egan, Robin Hood and Little John: Or, The Merry Men of Sherwood Forest (1840).

Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire (1883).

Modern

Reginald De Kovan, Robin Hood (1890).

Robin Hood (1922). Dir. Allan Dwan. Perfs. Douglas Fairbanks (Robin Hood), Alan Hale (Little John).

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Dir. Michael Curtiz and William Keighley. Perfs. Errol Flynn (Robin Hood), Alan Hale (Little John).

Rogues of Sherwood Forest (1950). Perf. Alan Hale (Little John).

The Adventures of Robin Hood. Perfs. Richard Greene (Robin Hood), Archie Duncan (Little John). ITV / Sapphire Films (1955-1958).

Robin of Sherwood. Perfs. Michael Praed (Robin Hood-Loxley), Jason Connery (Robin Hood-Huntingdon), Clive Mantle (Little John). HTV (1984-86).

Robin McKinley, The Outlaws of Sherwood (1989).

Robin Hood (1991). Dir. John Irvin. Perfs. Patrick Bergin (Robin Hood), David Morrissey (Little John).

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991). Dir. Kevin Reynolds. Perfs. Kevin Costner (Robin Hood), Nick Brimble (Little John).

Parke Godwin, Sherwood (1991).

Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993). Dir. Mel Brooks. Perfs. Cary Elwes (Robin Hood), Eric Allan Kramer (Little John).

Jennifer Roberson, Lady of the Forest (1993).

The New Adventures of Robin Hood Perf. Matthew Porretta (Robin Hood), John Bradley (Robin Hood), Richard Ashton (Little John). Baltic Ventures International (1996-98).

Michael Cadnum, Forbidden Forest (2002).

Robin Hood. Perf. Jonas Armstrong (Robin Hood), Gordon Kennedy (Little John). BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions (2006-08).

Works Cited

Bellenden, John. History and Chronicles of Scotland. (circa 1536-40) 2 vols. Edinburgh: W. & C. Tait, 1821.

Blunk, Laura. "'And for best supporting hero...Little John.'" Bandit Territories: British Outlaws and Their Traditions. Ed. Helen Phillips. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2008.

Holt, J. C. Robin Hood. Rev. ed. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

Knight, Stephen. Robin Hood: A Complete Study of the English Outlaw. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994.

Knight, Stephen and Thomas Ohlgren, eds. Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

Mapstone, Sally. "Shakespeare and Scottish Kingship: A Case History". The Rose and the Thistle: Essays on the Culture of Late Medieval and Renaissance Scotland. Eds. Sally Mapstone and Juliette Wood. East Linton, Scotland: Tuckwell Press, 1998.

Royan, Nicola. "The Relationship Between the Scotorum historia of Hector Boece and John Bellenden's Chronicles of Scotland". The Rose and the Thistle: Essays on the Culture of Late Medieval and Renaissance Scotland. Eds. Sally Mapstone and Juliette Wood. East Linton, Scotland: Tuckwell Press, 1998.

Read Less

The early ballad tradition consists of four texts: Robin Hood and the Monk, Robin Hood and the Potter, A Gest of Robyn Hode, and Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne. The dating of these four texts is uncertain and under continual revision; nevertheless, all appear to have been in circulation by the early years of the 16th century, and were firmly established before 1600. Little John appears prominently in all four. In Monk, particularly, John is far more heroic and central to the poem than its titular hero, and the plot focuses on John's efforts to free Robin from the Sheriff's prison. John is not without flaws that present contemporary audiences with a serious moral dilemma: as part of his plan to free Robin, John stalks, entraps, murders, and steals the identity of the monk who betrayed Robin to the Sheriff. John and Much travel to meet the King in the monk's place and deliberately deceive him in order to gain access to documents stamped with the royal seal; they then use these official documents to gain entry to fortified Nottingham and to free Robin Hood. Arguably, John's actions reflect Robin Hood's own attitudes—Robin is not a pleasant personality in this story—and Robin appears to acknowledge this codependency when he offers John leadership of the outlaw band. In A Gest, John is a major player, prompting Robin to greater charity for the poor knight and engaging in an independent adventure. In Guy, the ballad's focus is split between John and Robin, though the emphasis remains upon Robin: each outlaw has his own adventure, and they are reunited when Robin, disguised as Guy, rescues John from the Sheriff's clutches. John plays a minor role in Potter, despite an appearance in the opening lines. Interestingly, though critics frequently notice the traditional lyrical greenwood opening which appears in three of the four early ballads (missing only from A Gest), John's presence in the opening of all four ballads generally goes unexamined.

The early ballad tradition consists of four texts: Robin Hood and the Monk, Robin Hood and the Potter, A Gest of Robyn Hode, and Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne. The dating of these four texts is uncertain and under continual revision; nevertheless, all appear to have been in circulation by the early years of the 16th century, and were firmly established before 1600. Little John appears prominently in all four. In Monk, particularly, John is far more heroic and central to the poem than its titular hero, and the plot focuses on John's efforts to free Robin from the Sheriff's prison. John is not without flaws that present contemporary audiences with a serious moral dilemma: as part of his plan to free Robin, John stalks, entraps, murders, and steals the identity of the monk who betrayed Robin to the Sheriff. John and Much travel to meet the King in the monk's place and deliberately deceive him in order to gain access to documents stamped with the royal seal; they then use these official documents to gain entry to fortified Nottingham and to free Robin Hood. Arguably, John's actions reflect Robin Hood's own attitudes—Robin is not a pleasant personality in this story—and Robin appears to acknowledge this codependency when he offers John leadership of the outlaw band. In A Gest, John is a major player, prompting Robin to greater charity for the poor knight and engaging in an independent adventure. In Guy, the ballad's focus is split between John and Robin, though the emphasis remains upon Robin: each outlaw has his own adventure, and they are reunited when Robin, disguised as Guy, rescues John from the Sheriff's clutches. John plays a minor role in Potter, despite an appearance in the opening lines. Interestingly, though critics frequently notice the traditional lyrical greenwood opening which appears in three of the four early ballads (missing only from A Gest), John's presence in the opening of all four ballads generally goes unexamined. The modern era of Robin Hood materials, and thus of John as well, owes a substantial debt to Pyle's illustrations in The Merry Adventures. Alan Hale's casting as Little John in the two major films of the modern tradition—the production starring Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., in 1922 and that starring Errol Flynn in 1938— as well as a more obscure third film, Rogues of Sherwood Forest in 1950, cemented the character's general standing in filmed versions of the legend, despite the differences in Hale's performances from production to production. Physically, John has had more consistency than Robin: he is nearly always tall, usually dark-haired and bearded—though he has been blond and clean shaven, he is usually a physical contrast to Robin—and is nearly always the voice of reason. Consequently, he is often portrayed as being older than Robin and often serves as a paternal stand-in, either for Robin or, as with Hale's final turn in the role, to Robin's own child. In the last thirty years, particularly in filmed productions—whether for cinema or television—John's character has been portrayed as tall, bearded, with dark curly hair and a slightly sub-par intellect but superior empathetic capabilities, generally a father and family man; in sum, a tamed wild man. Laura Blunk identifies 1975-76 as the pivotal years for this reworking of Little John's character, with his appearences in the BBC miniseries The Legend of Robin Hood (1975) and Robin and Marian (1976) as models which all later filmed versions of the character draw upon (Blunk 209). Clive Mantle (Robin of Sherwood, 1984-86), David Morrissey (Robin Hood, 1991), Nick Brimble (Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, 1991), and Gordon Kennedy (Robin Hood, 2006-2008) have all played the character in this mode. Deviations from the model include blonds Eric Allan Kramer (Robin Hood: Men in Tights, 1993) and Richard Ashton (The New Adventures of Robin Hood, 1996-98). Written texts have taken their cues from their filmed counterparts, and though various novelists present John as alternately complex, simple, or a good man caught up in bad circumstances, his characterization in fiction is not significantly different from that found in the filmed tradition.

The modern era of Robin Hood materials, and thus of John as well, owes a substantial debt to Pyle's illustrations in The Merry Adventures. Alan Hale's casting as Little John in the two major films of the modern tradition—the production starring Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., in 1922 and that starring Errol Flynn in 1938— as well as a more obscure third film, Rogues of Sherwood Forest in 1950, cemented the character's general standing in filmed versions of the legend, despite the differences in Hale's performances from production to production. Physically, John has had more consistency than Robin: he is nearly always tall, usually dark-haired and bearded—though he has been blond and clean shaven, he is usually a physical contrast to Robin—and is nearly always the voice of reason. Consequently, he is often portrayed as being older than Robin and often serves as a paternal stand-in, either for Robin or, as with Hale's final turn in the role, to Robin's own child. In the last thirty years, particularly in filmed productions—whether for cinema or television—John's character has been portrayed as tall, bearded, with dark curly hair and a slightly sub-par intellect but superior empathetic capabilities, generally a father and family man; in sum, a tamed wild man. Laura Blunk identifies 1975-76 as the pivotal years for this reworking of Little John's character, with his appearences in the BBC miniseries The Legend of Robin Hood (1975) and Robin and Marian (1976) as models which all later filmed versions of the character draw upon (Blunk 209). Clive Mantle (Robin of Sherwood, 1984-86), David Morrissey (Robin Hood, 1991), Nick Brimble (Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, 1991), and Gordon Kennedy (Robin Hood, 2006-2008) have all played the character in this mode. Deviations from the model include blonds Eric Allan Kramer (Robin Hood: Men in Tights, 1993) and Richard Ashton (The New Adventures of Robin Hood, 1996-98). Written texts have taken their cues from their filmed counterparts, and though various novelists present John as alternately complex, simple, or a good man caught up in bad circumstances, his characterization in fiction is not significantly different from that found in the filmed tradition.