Be holde wele Frere Tuke

Howe he dothe his bowe pluke

—Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham(ll. 31-32)

Friar Tuck has enjoyed a relatively uncomplicated literary existence within the context of the Robin Hood tradition. His personality may alternate between cheerful and solemn, contemplative and self-absorbed, even gluttonous and parsimonious, but he is always a friar, sometimes a priest, and usually the member of Robin Hood's band who consistently stands out for his independence and affiliation with a system of belief that extends beyond the limits of the outlaws' own environs. His association with the traditions of both Robin Hood and May Day celebrations is particularly notable and is well documented beginning in the (post-medieval) Tudor era under the reign of Henry VIII.

The literary image of Friar Tuck as a plump and cheerful mendicant seems to be rooted partially in late Tudor drama, and more strongly in comedic texts and operettas produced in the second half of the nineteenth century. Notably, the introduction of Friar Tuck into the Robin Hood tradition slightly predates, but largely parallels, the inclusion of Maid Marian. What follows is a brief analysis of Friar Tuck's characteristics during three major periods of the tradition's development: the earliest materials available, up to the middle of the seventeenth century, the stepping stone texts of the eighteenth through nineteenth centuries, and the advent of film and novels in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

EARLY

Like Robin Hood, Friar Tuck enters the historical record considerably in advance of the first surviving literary appearance of the character. The name Friar Tuck first appears in royal English writs issued in 1417 and 1429. Per J. C. Holt, the

...Read More

Read Less

Be holde wele Frere Tuke

Howe he dothe his bowe pluke

—Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham(ll. 31-32)

Friar Tuck has enjoyed a relatively uncomplicated literary existence within the context of the Robin Hood tradition. His personality may alternate between cheerful and solemn, contemplative and self-absorbed, even gluttonous and parsimonious, but he is always a friar, sometimes a priest, and usually the member of Robin Hood's band who consistently stands out for his independence and affiliation with a system of belief that extends beyond the limits of the outlaws' own environs. His association with the traditions of both Robin Hood and May Day celebrations is particularly notable and is well documented beginning in the (post-medieval) Tudor era under the reign of Henry VIII.

The literary image of Friar Tuck as a plump and cheerful mendicant seems to be rooted partially in late Tudor drama, and more strongly in comedic texts and operettas produced in the second half of the nineteenth century. Notably, the introduction of Friar Tuck into the Robin Hood tradition slightly predates, but largely parallels, the inclusion of Maid Marian. What follows is a brief analysis of Friar Tuck's characteristics during three major periods of the tradition's development: the earliest materials available, up to the middle of the seventeenth century, the stepping stone texts of the eighteenth through nineteenth centuries, and the advent of film and novels in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

EARLY

Like Robin Hood, Friar Tuck enters the historical record considerably in advance of the first surviving literary appearance of the character. The name Friar Tuck first appears in royal English writs issued in 1417 and 1429. Per J. C. Holt, the drafters of the 1417 writ had apparently never heard the name before (Holt 59). However, by the time the 1429 writ had been issued, a connection had been established between the man called Friar Tuck in 1417 and the subject of the 1429 document: he was identified as a chaplain from Sussex who used "Friar Tuck" as a nom de guerre, and the 1429 writ links him to the prior document and lists his real name as Robert Stafford. Significantly, this historical "Friar Tuck" has no verifiable contemporary connection to the Robin Hood tradition: as Holt notes, the drafters of the 1417 writ were not aware that "Friar Tuck" was an alias (59), which they surely would have known if Tuck had already been absorbed wholesale into the Robin Hood traditions. By 1429, Stafford's true name was known, but the connection to the Robin Hood tradition is not remarked upon. As Allen Wright notes, "[t]his chaplain may have employed an alias from a pre-existing legend, but it's quite possible that he was the first to use the name of Tuck" (Wright "Friar Tuck"). Whether Stafford created the name or whether he was borrowing from a tradition is unknown; it is known that in 1417 and 1429, Friar Tuck was not yet connected to the Robin Hood tradition.

Popular culture frequently sets stories in the Robin Hood tradition during the lives and reigns of Richard I (b. 1157, r. 1189-99) and John (b. 1167, r. 1199-1216), a precedent which can be traced to John Major's Historia Majoris Britanniae of 1521 and Anthony Munday's plays of 1598 and 1599. Friar Tuck is himself a character in those plays, The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1598) and The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1599). However, Munday's inclusion of Friar Tuck in events set at the turn of the thirteenth century are categorically inaccurate: simply put, friars as an institution did not exist during the reigns of Richard I and John. The first of the mendicant orders of friars, the Dominicans, was not established until 1216 (Rowland 49), the year of King John's death, and are generally held to have entered Britain in 1221 (Rowland 103)—a full two years prior to the foundation of the Franciscan order. Friar Tuck is most often visually affiliated to the Franciscans because of his brown habit. By contrast, the friar who appears in the mid-seventeenth century ballad "Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar" is associated with Fountains Abbey, a Cistercian monastery, and a 1509 Kingston morris dance performance required a white coat, which would affiliate the friar with the Carmelite order (Forrest 156). Tuck's defining characteristic as a friar is indicative of the fundamentally anachronistic nature of his inclusion in the Robin Hood tradition.

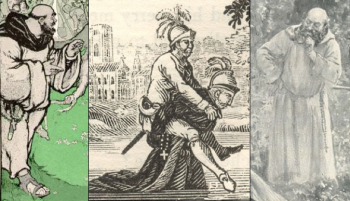

Traditional morris dances often feature a friar character. The presence of this character has resulted in the popular association of Friar Tuck with May Day and morris celebrations. Early Tudor dramatic references to the character certainly place him in this context. There is debate regarding how Tuck became affiliated with Robin Hood, whether through the morris tradition or through plays. The first record of a Robin Hood play dates to 1426-27, and that play's content is completely unknown. Furthermore, as John Forrest notes in his seminal The History of Morris Dancing, 1458-1750, "morris dancing does not show up in the English records until the second half of the fifteenth century" (Forrest 7), so after 1450. Forrest finds the earliest reference to the morris in a will from 1458, with other definitive references in 1477 and 1494 (Forrest 47) and potential examples in 1458 and 1466-67 (Forrest 47-48). These are all very general references, and do not list or describe individual figures within the dance. The famous Betley morris window—incorrectly dated to c. 1500 by the antiquarian George Tollett in 1793, an error which has lingered for centuries—is now considered to have been created around 1621 (Forrest 153). The Betley window is thus now not considered to be at all contemporary with the early introduction of morris dancing. Several of the Betley images are slightly modified copies of engravings made originally by the German engraver Israel van Meckenhem (c. 1445-1503). But Forrest argues that the Betley window's images contain distinctly English details, such as the friar. Furthermore, the friar figure (pictured here at left) is not present in the German fifteenth-century van Meckenhem originals (Forrest 155-56). Nor is this friar named as Tuck; as Forrest notes with regards to Tuck and the Kingston morris of 1509, "it would seem that either [the figure's] precise ecclesiastical affiliation was less important than his being a friar – that is, a mendicant with a mission to the world at large, rather than a cloistered monk – or that the friar was not a single fixed character (that is, was not specifically Friar Tuck)" (Forrest 156). Recall furthermore the 1417 reference to Robert Stafford's use of the name "Friar Tuck" as a nom de guerre. Stafford's use of the name before the introduction of morris dances to England indicates that Friar Tuck is not exclusively a product of the morris tradition.

Traditional morris dances often feature a friar character. The presence of this character has resulted in the popular association of Friar Tuck with May Day and morris celebrations. Early Tudor dramatic references to the character certainly place him in this context. There is debate regarding how Tuck became affiliated with Robin Hood, whether through the morris tradition or through plays. The first record of a Robin Hood play dates to 1426-27, and that play's content is completely unknown. Furthermore, as John Forrest notes in his seminal The History of Morris Dancing, 1458-1750, "morris dancing does not show up in the English records until the second half of the fifteenth century" (Forrest 7), so after 1450. Forrest finds the earliest reference to the morris in a will from 1458, with other definitive references in 1477 and 1494 (Forrest 47) and potential examples in 1458 and 1466-67 (Forrest 47-48). These are all very general references, and do not list or describe individual figures within the dance. The famous Betley morris window—incorrectly dated to c. 1500 by the antiquarian George Tollett in 1793, an error which has lingered for centuries—is now considered to have been created around 1621 (Forrest 153). The Betley window is thus now not considered to be at all contemporary with the early introduction of morris dancing. Several of the Betley images are slightly modified copies of engravings made originally by the German engraver Israel van Meckenhem (c. 1445-1503). But Forrest argues that the Betley window's images contain distinctly English details, such as the friar. Furthermore, the friar figure (pictured here at left) is not present in the German fifteenth-century van Meckenhem originals (Forrest 155-56). Nor is this friar named as Tuck; as Forrest notes with regards to Tuck and the Kingston morris of 1509, "it would seem that either [the figure's] precise ecclesiastical affiliation was less important than his being a friar – that is, a mendicant with a mission to the world at large, rather than a cloistered monk – or that the friar was not a single fixed character (that is, was not specifically Friar Tuck)" (Forrest 156). Recall furthermore the 1417 reference to Robert Stafford's use of the name "Friar Tuck" as a nom de guerre. Stafford's use of the name before the introduction of morris dances to England indicates that Friar Tuck is not exclusively a product of the morris tradition.

There are strong connections between Friar Tuck and dramatic productions. The first surviving Robin Hood play, Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham, dates to approximately 1475. The play is the first specific reference to Friar Tuck in the context of the Robin Hood tradition. Though Forrest speculates that Tuck diverged from the Robin Hood tradition at this stage, even as Marian was converging with the tradition (157), his data does not support his conclusion that the 1475 play represents Tuck's departure from the tradition. In fact, the 1475 play is the earliest document in which Friar Tuck participates in one of Robin's adventures. Earlier references, such as the 1417 writ, are to Tuck alone. Tuck cannot diverge from a tradition with which he was not previously connected.

By the sixteenth century Friar Tuck was a part of the Robin Hood tradition. Tudor dramatists deployed Friar Tuck in their plays far more frequently than their medieval predecessors. Sir Richard Morison, propagandist to Henry VIII, complains in "A Discourse Touching the Reformation of the Lawes of England," that "ther be playes of Robyn hoode, mayde Marian, freer Tuck, wherin besides the lewdenes and rebawdry that ther is opened to the people, disobedience also to your officers, is tought" (Anglo 179). The Morison pamphlet, Sydney Anglo argues, "must have been written after the dissolution of the monasteries" (177). The dissolution began in 1536 and ended in 1541. The surviving copy of the pamphlet has been dated to 1542, though Anglo notes that many of the anti-papal practices which Morison advocates "appear to have been put into practice long before 1542" (177). In any case, Morison's "Discourse" is one of the most solid and dependable early references to plays of Robin Hood involving Friar Tuck. In October 1537, a play titled A New Enterlude Called Thersytes may have been performed, either at Oxford or in Henry VIII's court, though there is no record in the Stationers' Register (Axton 12-13). There is one reference to Friar Tuck, notably separate from a reference to Robin Hood and Little John ("Where is Robin John and Little Hode?" l. 318, Axton 46), in which the hero Thersites—who is fighting a snail—casts away his weapon and informs his invertebrate opponent that "I wyll make the or I go for to ducke / And thou were as tale a man as Frier Tucke" (ll. 449-50, Axton 50).

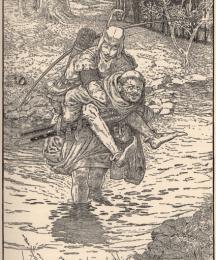

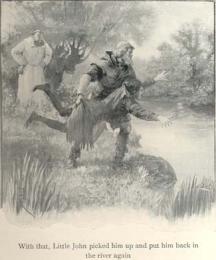

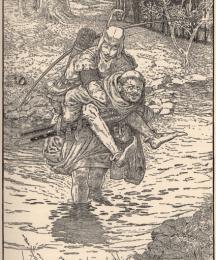

In the 1560s, the Copland print edition of A Mery Geste of Robyn Hoode and of Hys Lyfe appeared, and included the early plays Robin Hood and the Potter and Robin Hood and the Friar. The friar is called Tuck in marginal notes aligning character names with particular lines, and also in line 87 when Tuck, fighting Robin, exclaims "Than have a stroke fro Fryer Tucke". The exact date of Copland's text is uncertain, though 1560 is generally given: Knight and Ohlgren note that Copland's Potter and Friar presumably jointly comprise the "the play of Robyn Hoode" which Copland entered in the Stationers' Register in 1560, but the Mery Geste was printed some time between 1549 and 1569 (Knight and Ohlgren 281). The Copland Tuck is an exceptionally violent and bawdy man, entering the scene with boasts of his martial prowess and desire to fight with Robin Hood. After the combat with Robin, which features the first appearance of the famous scene in which Tuck dumps Robin in a river after being forced to carry him on his back—notable since the play appears nearly one hundred years before the Percy Folio's 1663 printing of "Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar" (Knight and Ohlgren 283)—Robin gives Tuck a "lady free." The introduction of the "lady free" begins a series of alternately solemn and riotously ribald double references: the lady herself might be free born, but an equally strong possibility is that she is a prostitute. Though Robin's instructions are that Tuck become the lady's chaplain and that Tuck is "[t]o serve her for my sake" (line 114), Tuck immediately crows, "Here is a huckle duckle, / An inch above the buckle. / She is a trul of trust, / To serve a frier at his lust" (lines 115-18) ("Here is a exaggerated false phallus, / Extending an inch above the buckle. / She is a trollop (or prostitute) of quality, / To serve a friar's lust").

Despite the increasing association of Friar Tuck with Robin Hood stories during the Tudor era, some notable documents fail to explicitly link Tuck with the tradition. This could indicate that Tuck's connections to Robin Hood were still in flux, or it could indicate that the links are so strong that authors assumed audience awareness. Modern scholarship does not have enough information to make informed statements either way. What is certain, however, is that in 1592 the chronicler John Stow's Annales, or a Generale Chronicle of England referred to the 1417 writ which serves as the first mention of Friar Tuck in any capacity. Like the 1417 document, and the 1429 writ which followed it, Stow's chronicle entry makes no connection between Tuck and the Robin Hood tradition. Notably, however, Stow follows John Major's example and inserts Robin Hood into the reign of Richard I in the 1190s. Major's Historia Majoris Britanniae, published in 1521, was the first—and until Stow copied Major in his 1580 Chronicles of England, the only—document to place Robin Hood in the reigns of Richard and John. Stow's Annales was reprinted several times, and editions from 1592 and 1631 show no emendations of Tuck's firm association with the 1417 writ. Notably, however, Stow does not retroactively print Robert Stafford's name, which was unknown in 1417, with the entry discussing his activities under the nom de guerre Friar Tuck.

The division in Tuck's treatment in popular culture and the chronicle tradition is reflected in how William Shakespeare provides a much stronger link between Robin Hood and Friar Tuck than Stow. Shakespeare refers to Friar Tuck in Two Gentlemen of Verona, when the Third Outlaw exclaims that "By the bare scalp of Robin Hood's fat friar, / This fellow were a king for our wild faction!" (IV.i.ll. 36-37), a most explicit linking of Tuck with the Robin Hood tradition. However, Two Gentlemen of Verona is a play whose textual history is uncertain: some scholars, like Clifford Leech, propose a date of 1592-93, and Anne Barton (who finds Leech's argument unconvincing) notes that the very first mention of the play is in Francis Meres's 1598 Palladis Tamia: Wits Treasury, famous for its list of Shakespeare's early works (Barton 177). The Meres citation establishes 1598 as the upper limit for the play's composition, and hence its Friar Tuck reference. Whether or not the play performed in Meres's time included the reference to Friar Tuck is also unknown: Two Gentlemen of Verona survives only in the 1623 First Folio print, thus published at least 25 years after the play was performed, and this textual delay is significant. Despite the textual uncertainty, the Shakespearian reference is fascinating because--presuming a publication in the early to mid 1590s—although the chronicle tradition (as seen in the example of Stow) declines to explicitly connect Tuck with Robin Hood, playwrights like Shakespeare and his contemporary Anthony Munday were more than happy to establish those links despite their reliance on the chronicle tradition for inspiration. A few years later Anthony Munday's plays, The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1598) and The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1599) were available, featuring Friar Tuck as a minor character. These dramatic references to Friar Tuck, made during the golden age of Tudor drama under Elizabeth I, are only a handful among the many references made during the same period to Robin Hood himself. Tuck is still a very minor character in the tradition by the turn of the seventeenth century, and with the onset of the Reformation Friar Tuck's popularity quickly faded.

MIDDLE

In the mid-1750s, Thomas Percy (1729-1811; Bishop of Dromore 1782-1811) obtained a manuscript collection known today as the Percy Folio (British Library Additional MS 27879), from which he drew to create Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765). The manuscript is dated by various scholars to 1630-50, though the ages of the stories are varied. The collection begins with seven Robin Hood stories, and the third tale describes an encounter between Robin and a friar. The ballad is now called "Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar" but Percy titled it "Robine Hood & Fryer Tucke" in the Reliques, after the ballad's title in the manuscript. Contemporary scholars have adjusted the ballad's title because the friar is never named in the text itself; only the title links it to Tuck. The Percy title is likely an emendation by the Percy Folio copyist. Furthermore, the textual history of the story is primarily traceable through the Forresters Manuscript family of texts, which uses the "Curtal Friar" title.

The age of the ballad is somewhat nebulous: a printed version of the ballad can be dated to 1625 (Knight Forresters MS, xv), contemporary with the great ballad writer Martin Parker who published A True Tale of Robin Hood in 1631-32, but the Percy Folio and Forresters Manuscript versions are somewhat later. The Percy Folio is likely the very near contemporary of the recently identified Forresters Manuscript, which was likely produced in the 1670s. The Forresters MS also contains a variation on the encounter between Robin Hood and a friar. However, the Forresters version of the story is markedly different from the Percy version, and "it is more likely that the printed version has lost material which linked it with the ancestor of, in these instances, both Percy and Forresters" (Knight Forresters MS, 71). A similarity between the Percy and Forresters stories is the action of the story—Robin fights a friar—and the friar's lack of a name.

Bishop Percy's work has been harshly criticized for centuries, in no small part due to Percy's tendency to silently "correct" the texts he worked with. One of his critics was fellow antiquarian Joseph Ritson (1753-1803), whose collection of Robin Hood ballads in 1795 — Robin Hood: A Collection of all the ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, now extant, relative to that celebrated English Outlaw — nevertheless draws heavily on Percy's Reliques. Ritson, like Percy, collected ballads; unlike Percy, but evidently much like the compiler of the Forresters MS a century earlier, Ritson sought to collect every extant Robin Hood ballad that he could find. Under Ritson's hand, Robin Hood moved from historical oddity to a worthy object of scholastic inquiry. Ritson's 12-page "The Life of Robin Hood," which prefaced the collection of ballads, is the first academic discussion of the Robin Hood tradition. The "Life" is supported by 117 pages of scholarly apparatus, modestly titled "Notes and Illustrations." Though Ritson's scholarship is seriously flawed and his methodology has been heavily criticized, the significance of his work is undeniable: Ritson's Robin Hood has been continuously reprinted for more than two centuries and remains a significant resource for students of the tradition.

Ritson's scholastic enterprise, though it added no new material to the Robin Hood tradition or to Tuck in particular, nevertheless opened doors to nineteenth-century authors examining contemporary social and political concerns through the safe, politically-expedient distancing effect of historical fiction.  Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe (1819) is one of the most influential treatments of Robin Hood, and the first novel to use Robin Hood as a significant character. Stephen Knight notes that "Scott knew Ritson's work well, and had little taste for the man or his politics" and thus marginalized Robin Hood, a character whom Scott saw as "distinctly anti-authoritarian" (Knight Robin Hood, 176). Scott's Tuck is in strong contrast to the somber, sober, and very much behind-the-scenes Robin Hood. This Tuck is very much the Tuck known to modern filmgoers: a round and cheerful hard-drinking, food-loving hermit, dressed alternately in the gray robes of a Franciscan friar and the green cloth of Robin Hood's band, a fighting friar ready to take on the world. From Tuck's first appearance in Chapter 16, Scott refers to the character alternately as a hermit, a clerk (of Copmanhurst), a friar, and a priest, and thus positions him to gain the trust of the Black Knight, the disguised King Richard. Tuck's role as a jolly militant, in touch with the earthly world, situates him simultaneously as a figure of typically hearty, vigorous, and masculine Saxon fortitude, and also as a potential target for criticism of the perceived corruption of the Roman Catholic church—a corruption accelerated by what many nineteenth-century British audiences perceived as the Norman Conquest's destruction of a mythologically "pure" Saxon church (Barczewski 127-28).

Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe (1819) is one of the most influential treatments of Robin Hood, and the first novel to use Robin Hood as a significant character. Stephen Knight notes that "Scott knew Ritson's work well, and had little taste for the man or his politics" and thus marginalized Robin Hood, a character whom Scott saw as "distinctly anti-authoritarian" (Knight Robin Hood, 176). Scott's Tuck is in strong contrast to the somber, sober, and very much behind-the-scenes Robin Hood. This Tuck is very much the Tuck known to modern filmgoers: a round and cheerful hard-drinking, food-loving hermit, dressed alternately in the gray robes of a Franciscan friar and the green cloth of Robin Hood's band, a fighting friar ready to take on the world. From Tuck's first appearance in Chapter 16, Scott refers to the character alternately as a hermit, a clerk (of Copmanhurst), a friar, and a priest, and thus positions him to gain the trust of the Black Knight, the disguised King Richard. Tuck's role as a jolly militant, in touch with the earthly world, situates him simultaneously as a figure of typically hearty, vigorous, and masculine Saxon fortitude, and also as a potential target for criticism of the perceived corruption of the Roman Catholic church—a corruption accelerated by what many nineteenth-century British audiences perceived as the Norman Conquest's destruction of a mythologically "pure" Saxon church (Barczewski 127-28).

The other major Robin Hood novel of the early nineteenth century is Thomas Love Peacock's Maid Marian, completed in 1822 but begun years earlier: Scott and Peacock were both working on Robin Hood novels simultaneously. Peacock's friar is a monk, Father Michael of Rubygill Abbey, who takes the forest name of Friar Tuck, much as Matilda Fitzwater becomes Maid Marian, and Robert FitzOoth becomes Robin Hood. The Tuck of Maid Marian is an active participant in the outlaw "court," serving as third in command of the band. Furthermore, Tuck adroitly articulates Robin's greenwood philosophy in a debate and thus wins King Richard's respect. Unlike Scott, who tapped into simplistic nationalism, the rising tide of racialism, and the eternally popular myth of the Norman Yoke, Peacock's work is, as Knight notes, "both a remarkable achievement and also a dead end in literary terms. His ironic touch is too light for lesser writers to imitate, his structure too economically interlinked for the three-volume men to expand with success [....] The elusive and anti-authoritarian hero of the outlaw myth meets in Peacock an author equally hard to pin down" (Knight Robin Hood, 186, 182). In sum, Peacock's Tuck is no corrupt friar whose gluttony and insincere piety provide material for comedy or critique; rather, he is a devout man whose connections to the political and cultural fabric of his society are exceptionally strong. Peacock's Tuck is used to criticize the nineteenth-century tendency to present the medieval as ideal.

While Scott and Peacock were working on novels incorporating Robin Hood materials in 1818-19, other prominent literary figures including John Keats, John Hamilton Reynolds, and Leigh Hunt were crafting poetic reinterpretations of the traditional materials. Unlike the novelists, the poets did not find much use for Friar Tuck: Keats and Reynolds make absolutely no use of the character, and while Hunt refers to friars in all four of his Robin Hood ballads, they are distinctly, with a single exception, the faceless enemy of greenwood liberty. Knight speculates that Hunt began working on the poems in 1818, for he read Keats's "Robin Hood" the day after it was written (Knight Robin Hood, 167; citing John Barnard, "Keats's 'Robin Hood'," John Hamilton Reynolds and the 'Old Poets'," Proceedings of the British Academy 75: 198) and published his own poetry in The Indicator in early 1820; the poems were not collected until 1855, when Hunt published Stories in Verse (Knight Robin Hood, 167). Though he proved fascinating and useful to the novelists of 1818-19, Tuck held no attraction for the poets.

Tuck's poetic drought endured until 1839, when an anonymous modern ballad, anachronistically titled "Robyn Hode and Kynge Richarde," appeared in Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country 19.113 (May 1839): 593-603. The Fraser's Magazine ballad has no authorial attribution in the publication but an article attributed to "G. F.," and printed in The London and Westminster Review 33.65 (March 1840) 231-63, credits one Allan Cunningham with authorship of "Robyn Hode and Kynge Richarde." Cunningham's poem makes explicit the connection between the seventeenth-century ballad "Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar" and Friar Tuck:

And there was the merrye curtall frere,

His name was Fryar Tucke;

No man of all bold Robin's band

Could better kyll a bucke.

Or at a bout of quarter-staffe

Could by kewise better playe;

Or run, or wrestle, synge, or laughe,

Or even better praye. (33-40)

Tuck's hunting and martial abilities are thus immediately foregrounded. In fact, Tuck's martial prowess is emphasized above all the other outlaws: Robin Hood is "a gentyl outlawe" (l. 21), Little John is "a faythful sqyre" (l. 26) and very tall, Will Scarlet and Much the Miller's son are mentioned, along with George-a-Green, Allan a-Dale, and Marian. But it is Tuck who receives two whole stanzas discussing his deer-killing abilities, skill with the quarter staff and at wrestling, along with more traditionally "jolly" activities such as singing and laughing. Tuck's role in the ballad is minimal, despite the sustained introduction; in this, as in so much else, the ballad mirrors the expectations of Tuck, and of the Robin Hood tradition more generally, established by Scott's Ivanhoe.

Despite Tuck's sporadic popularity, interest in the Robin Hood tradition skyrocketed in the first half of the nineteenth century. The impact of this revival of interest—which scholars like Barczewski and Knight have attributed to widespread social unrest stemming from the rapid industrialization of the United Kingdom—was felt in the United States as well. The American poet William Cullen Bryant wrote an editorial, "Friar Tuck Legislation," dated April 26, 1844. The editorial is in part a response to a comment made by the British parliamentarian Thomas Gisborne, who was a member of the Whig party, during a meeting of the Anti-Corn Law League. Bryant used Gisborne's allusion to Friar Tuck to simultaneously affirm the selfish dishonestly of Tuck—Bryant defines Friar Tuck Legislation as regulation designed and enacted for the benefit of the law maker—and to praise the "frankness in his philosophy which throws the sneaking duplicity of the legislators of the cotton mills quite into the shade" (Bryant II 223).

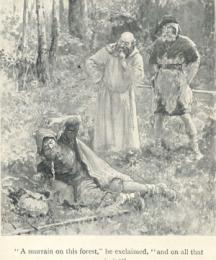

References to Friar Tuck during Queen Victoria's reign were rarely serious, despite the invocation of the tradition in highly-charged political matters. In 1858, E. L. Blanchard's play Robin Hood; Or, Harlequin Friar Tuck, and the Merrie Men of Sherwood Forest: An Entirely New grand magical, comical, pastoral, and peculiarly pantomimical pantomime, founded on the popular old English ballad of 'Robin Hood', was written. In 1881, George Thorne and F. Grove Palmer wrote Robin Hood and Little John, Or Harlequin Friar Tuck, and the 'Merrie Men' of Sherwood Forest. Between these plays, which prominently feature Tuck in a comedic role, and the musicals of Reginald DeKoven (Robin Hood in 1890 and Maid Marian in 1901), the focus on Tuck's martial abilities began to fade in performance in favor of his comedic potential. Literary representation of Tuck during the same period merely repeated old themes: Howard Pyle's influential 1883 reworking of the Robin Hood tradition expanded and deepened the meeting between the Curtal Friar—finally named as Tuck at the end of the story—and Robin Hood, but added no new material. Likewise, Sebastian Evans's "Of Robin Hood's Death and Burial" in 1865 refers to Tuck, but he does not appear within the actions of the poem.

MODERN

Friar Tuck appears irregularly in the literary Robin Hood record of the early twentieth century, in texts which have only the Robin Hood tradition in common: Robert Alexander Wason produced the semi-biographical cowboy adventure Friar Tuck: Being The Chronicles Of The Reverend John Carmichael, of Wyoming, U.S.A. in 1912 and Alfred Noyes wrote the exultory "The Matin-Song of Friar Tuck" in 1918.

However, Friar Tuck became one of the mainstays of the cinematic Robin Hood tradition, probably due to his iconic appearance and his presence in the immensely popular DeKoven operettas. Despite the anachronism of placing a friar in late twelfth-century England, Friar Tuck appears in filmed media as frequently as Robin Hood and Little John. Unlike Robin and John, however, Tuck's costume has barely changed since it first appeared on screen in the 1922 blockbuster Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood. His robes are uniformly brown, made of coarse material, with a hood; he generally carries a sword, supported by a thick belt. His head is shaven in traditional monastic fashion, and he wears no beard.

As authors and filmmakers search out new approaches to the Robin Hood tradition, Tuck has become an increasingly popular choice. He appears in every filmed Robin Hood production and as a secondary character in many of the novels which appeared during the minor revival of interest in Robin Hood in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a revival which saw the simultaneous release of two films, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, starring Kevin Costner, and Robin Hood, starring Patrick Bergin (both 1991), the parody Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993) and several novels. In films, Tuck fares well, but his fate varies from book to book. Robin McKinley featured him as a lynchpin character in her young adult novel The Outlaws of Sherwood (1989), using the traditional ballad "Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar" by way of Howard Pyle as the basis for her version of the character. Parke Godwin's Tuck is a minor character, caught by the sheriff and hung mid-way through Sherwood (1991). Jennifer Roberson's Tuck in Lady of the Forest (1992), by contrast, is a significant character: a naïve monk from Croxton Abbey, sent to Nottingham to work as a clerk and to control his excessive appetite, this Tuck eventually flees the castle when the sheriff's demands finally overwhelm his moral obligations as a monk and aspiring priest.

In the twenty-first century, Tuck has enjoyed a surge in popularity in mass market textually-based media. He appears—as Frederick Tuckman—in the comic book Green Arrow 3.75 (2007). The story, "Jericho (Part III of III) - And the Walls Came Tumbling Down," sees the superhero Green Arrow arrange for Tuckman to take over his role as mayor of Star City. 2009 saw the publication of three Robin Hood novels; Tuck does not appear in Adam Thorpe's Hodd, but he does feature prominently in the other two books. Stephen Lawhead published Tuck, the final segment of his King Raven trilogy; the trilogy is a retelling of the Robin Hood tradition in the context of early twelfth-century Wales. Lawhead's Tuck is quiet, mousy, and not truly the main focus of the book. This Tuck, whose true name is Aethelfrith, is strangely very comfortable with the native religiosity that Lawhead's Robin Hood analog, Bran y Hud, prefers. Tuck is also quietly instrumental to wrapping up the main conflict of the story, serving as an intermediary and translator, and when Hud eventually swears fealty to King William II (called William Rufus, r. 1087-1100) and has his lands returned, 'Rule well and wisely,' said the king in English. He searched the crowd for a face, and found it. 'And see you keep this man close to your throne,' he said, pulling Tuck forward. 'He has done you good service. If not for him, there would be no peace to celebrate this day'" (425). In contrast to the quietly competent Tuck of Lawhead's trilogy is the Tuck of Paul A. Freeman's Robin Hood and Friar Tuck: Zombie Killers: A Canterbury Tale, a horror story which appropriates the narrative frame of Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. This Tuck is a hard-drinking and martial monk, who witnesses the initial zombie infection of Sir Guy of Gisborne's crusaders while he helps them besiege a castle in the Holy Land. When Guy brings the infection back to England, Tuck searches out Robin Hood to help him destroy the zombie menace and happily participates in the slaughter. Tuck is one of the few survivors of the bloodbath, and ultimately he retires with Little John to a hermit's cell in Sherwood.

Friar Tuck has altered remarkably little since the earliest literary connection of his character to the Robin Hood tradition in the 1475 play Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham. Visually, whether in illustration, film, or cover art, there is little significant variation in his costuming and garb, and thus Friar Tuck may serve as an unchanging icon of the Robin Hood tradition. In terms of character, Tuck is usually jolly and loud, with a tendency towards rough violence and crudeness. His alternate role, as the outlaws' token intellectual, serves to explicate story points, and is found largely in novels and television programs, whose complex plots and narrative concerns require explanation to audiences. Interestingly, Tuck's role as intellectual does not depend upon the Robin Hood character's social standing: even if Robin Hood or other characters can read and write, Tuck usually takes on those duties as well. More consistent is his position as the figure of primary comedic relief, largely dependent upon his casting as a big-bellied man with an open face and ready smile, a role which is rarely challenged in film and television and almost never in the later ballads and novels. Tuck's standing as a friar is inherently anachronistic when the Robin Hood tradition is set during the reigns of Richard I and John, to say nothing of the tendency by modern novelists to set the stories even earlier, in an attempt at historically-justifiable tension between invading Normans and oppressed native peoples. Despite this, and despite his clear standing as a representative of organized religion, Tuck often serves as a living embodiment of what is wrong with the Church, much as Robin Hood exists as a paradoxical embodiment and criticism of social standards. Tuck is both the embodiment of corruption which legitimate religious reform seeks to stamp out and the symbol of how much more honest, quotidian, and caring the clerical class could be. Despite this, he remains a mainstay of the Robin Hood tradition, and when he is missing from a retelling his exclusion is notable and significant. Like Robin Hood, Friar Tuck has become many things to many people, and he is open to interpretation and appropriation from all quarters.

Early

Royal Writ (1417) Available in Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry V, ed. Alfred Edward Stamp and William Henry Benbow Bird (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1929-32; 2 vols.).

Royal Writ (1429) Available in Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry VI. (London, H. M. Stationery Office, 1933-47. 6 vols.).

Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham (1475).

Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar (late 15th century).

The Betley Window, in the British Galleries of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK (c.1509-36).

"A Discourse Touching the Reformation of the Lawes of England," Sir Richard Morison (1536-41 ). Reprinted in SydneyAnglo, "An Early Tudor Programme for Plays and Other Demonstrations against the Pope," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 20.1-2 (1957): 176-179.

A New Enterlude Called Thersytes (1537). Reprinted in Marie Axton, Three Tudor Classical Interludes: Thersites, Jacke Jugeler, Horestes. (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1982).

Reference by Henry Machym (1559). Reprinted in The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant-Taylor of London, From A.D. 1550 to A.D. 1563, ed. John Gough Nichols (London: Camden Society, J.B. Nichols and Son, 1848).

A Mery Geste of Robyn Hoode and of Hys Lyfe, first printed by William Copland (1549-1569). Includes plays Robin Hood and the Potter and Robin Hood and the Friar. Facimile reprint (Amersham, England: J.S. Farmer, 1914).

John Stow, Annales: or, A Generall Chronicle of England (1592). Available from Early English Books Online.

William Shakespeare, Two Gentlemen of Verona (1592-98).

Anthony Munday, The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1598).

Anthony Munday, The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington (1599).

Middle

Thomas Percy, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1663).

Walter Scott, Ivanhoe: A Romance (1820).

Thomas Love Peacock, Maid Marian (1822).

Allan Cunningham, "Robyn Hode and Kynge Richard" (1839) Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. 19.113 (May 1839): 593-603.

E. L. Blanchard, Robin Hood; Or, Harlequin Friar Tuck, and the Merrie Men of Sherwood Forest: An Entirely New grand magical, comical, pastoral, and peculiarly pantomimical pantomime, founded on the popular old English ballad of "Robin Hood" (1858).

Sebastian Evans, "Of Robin Hood's Death and Burial" (1865).

George Thorne and F. Grove Palmer, Robin Hood and Little John, Or Harlequin Friar Tuck, and the "Merrie Men" of Sherwood Forest (1881).

Reginald De Koven and Harry B. Smith, Robin Hood: A Comic Opera in Three Acts (1890).

Reginald De Koven and Harry B. Smith, Maid Marian: A Comic Opera in Three Acts (1901).

Modern

Robert Alexander Wason, Friar Tuck: Being The Chronicles Of The Reverend John Carmichael, of Wyoming, U.S.A. (1912).

Alfred Noyes, "The Matin-Song of Friar Tuck" (1918).

Robin Hood (1922). Dir. Allan Dwan. Perfs. Douglas Fairbanks (Robin Hood), Willard Louis (Friar Tuck).

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Dir. Michael Curtiz and William Keighley. Perfs. Errol Flynn (Robin Hood), Eugene Pallette (Friar Tuck).

The Adventures of Robin Hood. Perfs. Richard Greene (Robin Hood), Alexander Gauge (Friar Tuck). ITV / Sapphire Films (1955-1958).

Robin Hood (1973). Dir. Wolfgang Reitherman. Perfs. Brian Bedford (Robin Hood), Andy Devine (Friar Tuck).

Robin and Marian (1976). Dir. Richard Lester. Perf. Sean Connery (Robin Hood), Ronnie Barker (Friar Tuck).

Robin of Sherwood. Perfs. Michael Praed (Robin Hood-Loxley), Jason Connery (Robin Hood-Huntingdon), Phil Rose (Friar Tuck). Goldcrest / HTV (1984-86).

Robin McKinley, The Outlaws of Sherwood (1989).

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991). Dir. Kevin Reynolds. Perfs. Kevin Costner (Robin Hood), Michael McShane (Friar Tuck).

Parke Godwin, Sherwood (1991).

Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993). Dir. Mel Brooks. Perfs. Cary Elwes (Robin Hood), Eric Mel Brooks (Rabbi Tuckman).

Jennifer Roberson, Lady of the Forest (1993).

The New Adventures of Robin Hood Perf. Matthew Porretta (Robin Hood), John Bradley (Robin Hood), Martyn Ellis (Friar Tuck). Baltic Ventures International (1996-98).

Green Arrow 3.75 (2007) "Jericho (Part III of III) - And the Walls Came Tumbling Down" as Frederick Tuckman.

Robin Hood. Perf. Jonas Armstrong (Robin Hood), David Harewood (Friar Tuck). BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions (3 series, 2006-09; Harewood as Tuck series 3, 2008-09).

David Lawhead, Tuck (2009).

Paul A. Freeman, Robin Hood & Friar Tuck: Zombie Killers: A Canterbury Tale (2009).

Robin Hood (2010). Dir. Ridley Scott. Perf. Russell Crowe (Robin Hood), Mark Addy (Friar Tuck).

Works Cited

Anglo, Sydney. "An Early Tudor Programme for Plays and Other Demonstrations against the Pope." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 20.1-2 (1957): 176-179.

Axton, Marie. Three Tudor Classical Interludes: Thersites, Jacke Jugeler, Horestes. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1982.

Barczewski, Stephanie L. Myth and National Identity in Nineteenth-Century Britain: The Legends of King Arthur and Robin Hood. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Barton, Anne. "Two Gentlemen of Verona." The Riverside Shakespeare. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans. 2nd edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997. Pp. 177-80.

Bryant, William Cullen. Power for Sanity: Selected Editorials of William Cullen Bryant, 1829-1861. Ed. William Cullen Bryant II. New York: Fordham University Press, 1994.

Cunningham, Allan. "Robyn Hode and Kynge Richard." Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. 19.113 (May 1839): 593-603.

"David Tucks In." Thesun.co.uk. The Sun, 18 Feb. 2009. Web. June 2010.

Forrest, John. The History of Morris Dancing, 1458-1750. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999.

Holt, J. C. Robin Hood. Rev. edition. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

Knight, Stephen Thomas. Robin Hood: A Complete Study of the English Outlaw. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1994.

---. Robin Hood: The Forresters Manuscript, British Library Additional MS 71158. Rochester, NY: D. S. Brewer, 1998.

---, and Thomas Ohlgren. Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

Rowlands, Kenneth W. The Friars: A History of the British Medieval Friars. Sussex: Book Guild Ltd., 1999.

Shakespeare, William. Two Gentlemen of Verona. The Riverside Shakespeare. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans. 2nd edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997. Pp. 181-207.

Wright, Allen. "Friar Tuck." Boldoutlaw.com. Robin Hood: Bold Outlaw of Barnsdale and Sherwood. Web. May 2010.

Read Less

Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar (Child Ballad No. 123A) - 1882-1889 (Author)

Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar (Child Ballad No. 123A) - 1882-1889 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar: Introduction - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Friar and Robin Hood and the Potter - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Friar and Robin Hood and the Potter: Introduction - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar: Introduction - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Friar and Robin Hood and the Potter - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and the Friar and Robin Hood and the Potter: Introduction - 1997 (Editor)

by Anthony Munday (Author), Stephen Knight (Editor)

by James Robinson Planché (Author), Henry Rowley Bishop (Composer)

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

by Stephen Knight (Editor), Thomas H. Ohlgren (Editor)

by Stephen Knight (Editor), Thomas H. Ohlgren (Editor)

by Stephen Knight (Editor), Thomas H. Ohlgren (Editor)

Images Gallery