We will continue to publish all new editions in print and online, but our new online editions will include TEI/XML markup and other features. Over the next two years, we will be working on updating our legacy volumes to conform to our new standards.

Our current site will be available for use until mid-December 2024. After that point, users will be redirected to the new site. We encourage you to update bookmarks and syllabuses over the next few months. If you have questions or concerns, please don't hesitate to contact us at robbins@ur.rochester.edu.

Guillaume de Machaut, The Boethian Poems: Le Remede de Fortune

MACHAUT, THE BOETHIAN POEMS: EXPLANATORY NOTES

Abbreviations: BD: Chaucer, Book of the Duchess, ed. Benson; CA: Gower, Confessio Amantis, ed. Peck; Confort: Machaut, Le Confort d’Ami; CP: Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy, trans. Stewart, Rand, and Tester; CT: Chaucer, Canterbury Tales, ed. Benson; Hassell: Hassell, Middle French Proverbs, Sentences, and Proverbial Phrases; HF: Chaucer, House of Fame; JRB: Machaut, Le Jugement dou Roy de Behaingne, ed. Palmer (2016); JRN: Machaut, Le Jugement dou Roy de Navarre, ed. Palmer (2016); LGW: Chaucer, Legend of Good Women, ed. Benson; OCD: Oxford Classical Dictionary, eds. Hornblower and Spawforth; OM: L’Ovide moralisé, ed. de Boer; OT: Old Testament, Douay-Rheims; Remede: Machaut, Remede de Fortune; RR: Roman de la Rose, trans. Dahlberg; TC: Chaucer, Troilus and Criseyde, ed. Benson; Whiting: Whiting, Proverbs, Sentences, and Proverbial Phrases.

LE REMEDE DE FORTUNE

1–25 Cils qui vuet . . . . malice son corage. More than any other Machaut dit, the Remede is deeply didactic, with the philosophizing of lady Esperence (Hope, a figure clearly modeled on Boethius’ Lady Philosophy) complemented by instruction in the love experience provided by the traditional figure of Amour. At stake is nothing less than the education of the youthful narrator, who passes from suffering to consolation, as he is brought to abandon misunderstanding for a sure knowledge about the most pressing of existential issues. This high theme is appropriately set by this remarkable opening passage, which meditates on learning, memory, and the maturing over time of the mind and feelings. The notion that any neophyte must attend to twelve related matters if he is to master any art seems traditional, but in fact no source for this material has been located, and it is likely original to Machaut. A brief allusion to this passage appears in BD, lines 794–96.

26–34 Car le droit . . . . en li empreinte. Machaut compares the wax tablet to youth and innocence. As Laurence de Looze describes it, the wax tablet represents “a pregeneric world ready to receive life’s writing but as yet uncontaminated by man’s scribbling . . . . the very opposite of a forme fixe,” (de Looze, Pseudo-Autobiography,” p. 85). See BD, lines 779–84, where Chaucer draws specifically on this passage.

45–386 Pour ce l’ay . . . . nul autre desir. Here, the narrator describes his lady love, highlighting how her virtuous and noble behavior inspired him. Ennobling love is a convention of love poetry. It is interesting to compare this account with that of the lover in JRB who prioritizes his lady’s physical beauty and grace (see especially lines 286–456), while the narrator of the Remede devotes only 23 lines to her appearance (lines 303–26) and spends much more time praising her virtues.

45–55 Pour ce lay dit . . . belle et bonne. Compare BD, lines 4–15 and 797–804. Machaut’s account of youth, idleness, and the unstable heart that under the influence Nature’s gifts makes all seem alike as the heart fixates on its lady might well factor into Gower’s invention of Amans and his persistent irrational (though much rationalized) behavior in the Confessio Amantis.

54–55 ma dame . . . . belle et bonne. Wimsatt and Kibler suggest that the reference in this passage to the lady as “bonne” (good) is the first of several punning references to Bonne of Luxembourg, the daughter of Jean of Bohemia. They argue that Bonne may well be not only the model for the lady in the Remede, but the patroness for whom it was composed (Roy de Behaingne and Remede de Fortune, pp. 33–35 and 492n54–56). This is an intriguing if unprovable possibility.

65–94 La veoie moult volentiers . . . . fais voloie entreprendre. On the power of the gaze in the love matters, compare Gower on sight as the “moste principal of alle” senses as the “firy dart / of love, which that evere brenneth” pierces the lover through the eyes and “into the herte renneth” (CA 1.304–24). Compare the Remede, line 97, on the interlocking of “mon cuer et a ses yex.” The beloved in Machaut, however, is much kinder to the lover than she is in Gower.

71 Amours. The allegorical figure here, unlike Youth and Nature, is a female force that is somewhat distinct from Cupid with his tyrannical arrows in RR, or the love figure that has “his dwellynge / Withinne the subtile stremes of [Criseyde’s] yen” (Chaucer, TC, 1.304–05).

107–27 Et certeinnement . . . . del tel affaire. The nine names Machaut cites here are traditional models of excellence. Of the Nine Worthies who were considered paradigms of chivalry, Alexander and Hector are two of the three Pagan Worthies (the third is Julius Caesar, not here mentioned). Godfrey de Bouillon is one of the three Christian Worthies (the second and third are Charlemagne and Arthur) . The catalogue of worthies or nonpareils (here five from the Bible and four from classical tradition) is a stock theme in medieval poetry. The less familiar are: Godfrey of Bouillon, leader of the First Crusade (1096–1099) and, after its successful conclusion, the first ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem; Absalom, the third son of Solomon, who was reputed to be the most handsome of men (see 2 Kings 14:25); Judith, the main figure in the deuterocanonical book of Judith, who was famed for tricking an enemy general, Holofernes, then decapitating him and saving her people from being conquered; and Esther, who in the canonical book that bears her name, is a Jewish maiden who becomes queen of Persia and foils a plot to destroy her people.

116 la biauté qu’ot Absalon. Compare Chaucer, LGW, Prol F, line 249.

123–24 Et avec ce l’umilité / Qu’Ester ot. See Chaucer, LGW, Prol F, line 250: “Ester, ley thou thy meknesse al adown.”

136 pris fui et loiaus amis. The imagery of the lover as captive is conventional. See also line 362.

142–66 Comment ma dame . . . . seul ne mespris. The instructions given by Love are thoroughly conventional. The Remede does not interrogate the literary tradition of fin’ amors (refined love) that by Machaut’s time was two centuries old, though Machaut was certainly inclined to do so since fundamental love questions are the focus in the two poems of the debate (or judgment) series: the JRB and JRN.

170 Plus que Paris ne fist Heleinne. The reference here is to the Troy story, known to the Middle Ages through Latin recensions, not Homer’s two poems. The Trojan Paris, with the assistance of Venus, wins the love of Helen, wife of the Greek nobleman Menelaus, who assists his brother Agamemnon in leading an expedition against Troy. After the deaths of Paris and many warriors on both sides, the Greeks take the city, and Helen is then re-united with Menelaus.

187–88 Qu’onques turtre . . . . coulons, ne coulombelle. All these animals are traditionally associated with peace and meekness.

245–47 Et se l’Evangile . . . . s’umilie essauciés. This is a version of two oft-quoted passages from the New Testament: Matthew 23:12 and Luke 14:11.

268–69 masitresse bonne . . . . a bonne escole. According to Wimsatt and Kibler, this is another punning reference to Bonne of Luxembourg (Roy de Behaingne and Remede de Fortune, p. 495n268–69). See also the note to lines 54–55 above.

308 Douce Esperence. Esperence makes a dramatic entrance that is deliberately evocative of the sudden appearance of Lady Philosophy in CP 1.

345–46 Pour ce que löange assourdist / En bouche qui de li la dist. Proverbial. See Whiting P351.

363–70 Car pour riens . . . . de s’amour. For an amusing account of the importance of keeping love secret, see Andreas Capellanus’ c. 1170 De Amore (The Art of Courtly Love), book 2, chapter 7 on “Various Decisions in Love Cases.”

371–76 Nompourquant quant de . . . . trambler et tressaillir. The poet describes the physical suffering of lovers. Lovesickness or love madness (Latin amor hereos) was, according to medieval physicians, “a disorder of the mind and body, closely related to melancholia and potentially fatal if not treated” (Wack, Lovesickness in the Middle Ages, p. xi). The symptoms mentioned here, especially a pale complexion, were conventional (p. 40). Machaut explicitly names love as a sickness in his lay, line 626.

401–30 Et pour ce . . . . qu’on claimme lay. Here the fictional poet explains how he found an outlet for his feelings by composing songs and poetry inspired by his love. At the same time, the real Machaut is presenting both a theory of poetry that places the author at the center of a body of works, and also the structure of the Remede, which includes the types of lyric he mentioned in this section. Sarah Kay suggests that the different formes fixes allow the poet to “respond to and articulate [a] variety of feelings” and refers to the inset lyrics as a “portfolio” (Kay, “Consolation, Philosophy and Poetry,” pp. 35, 34).

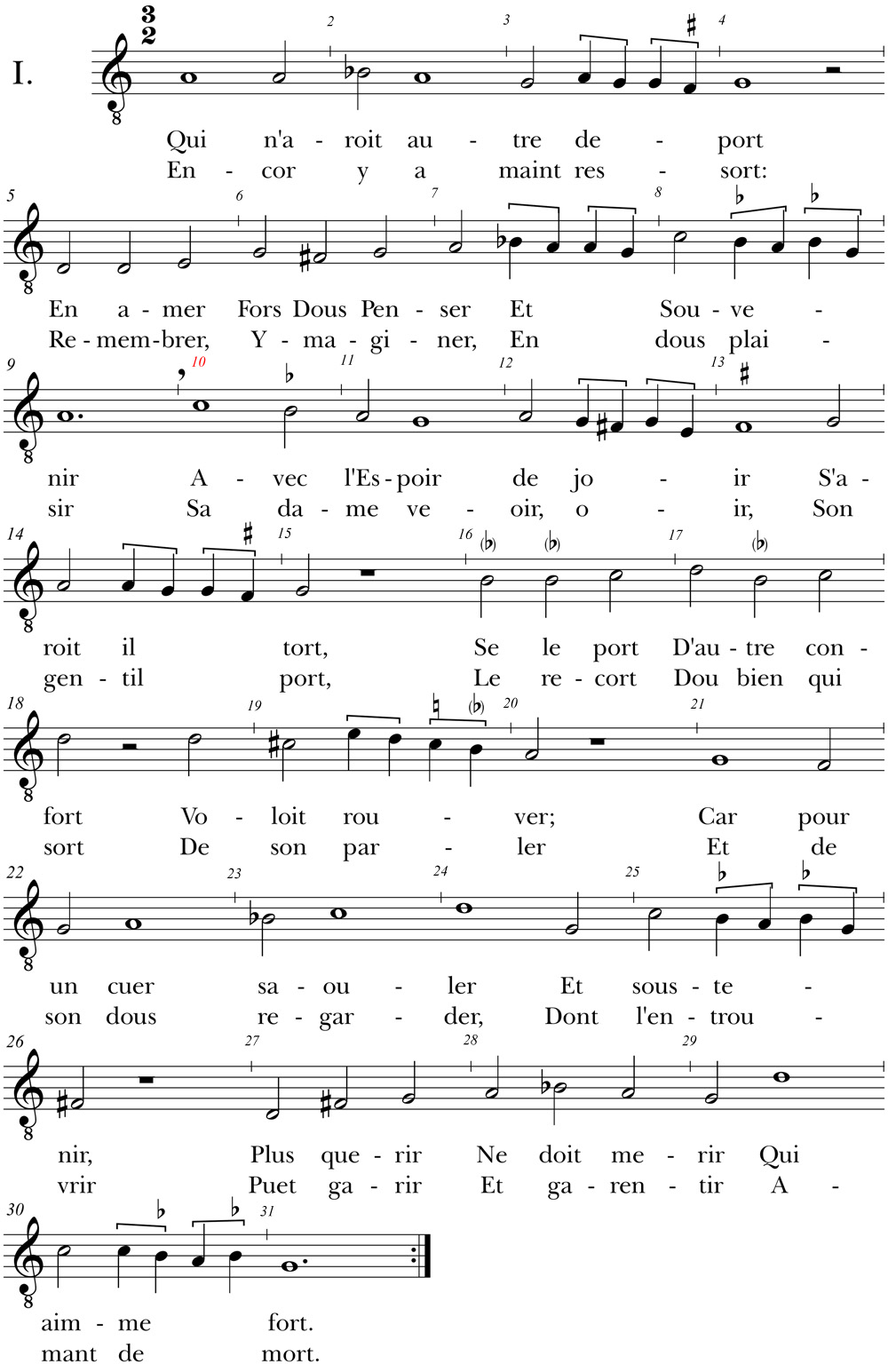

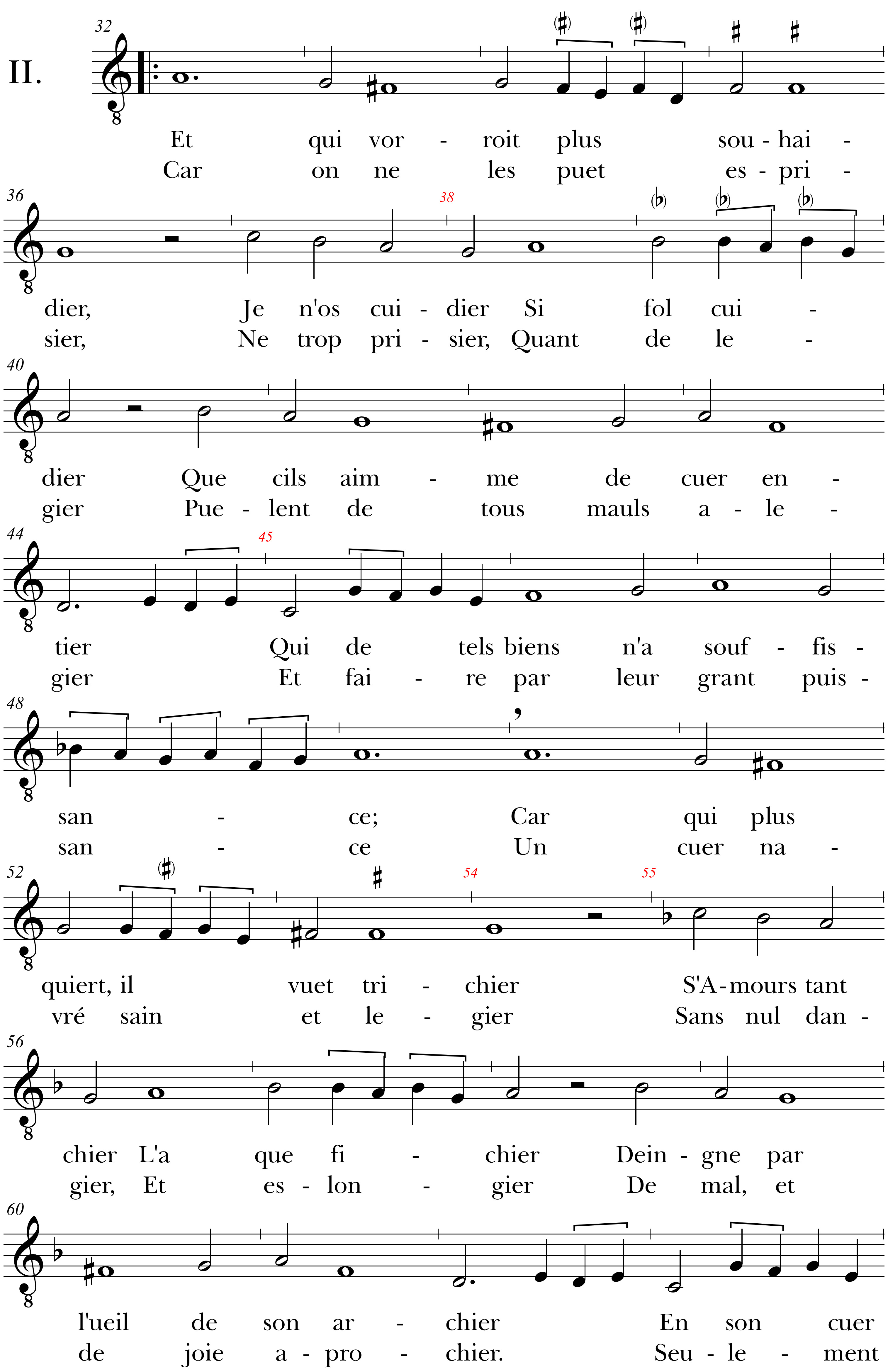

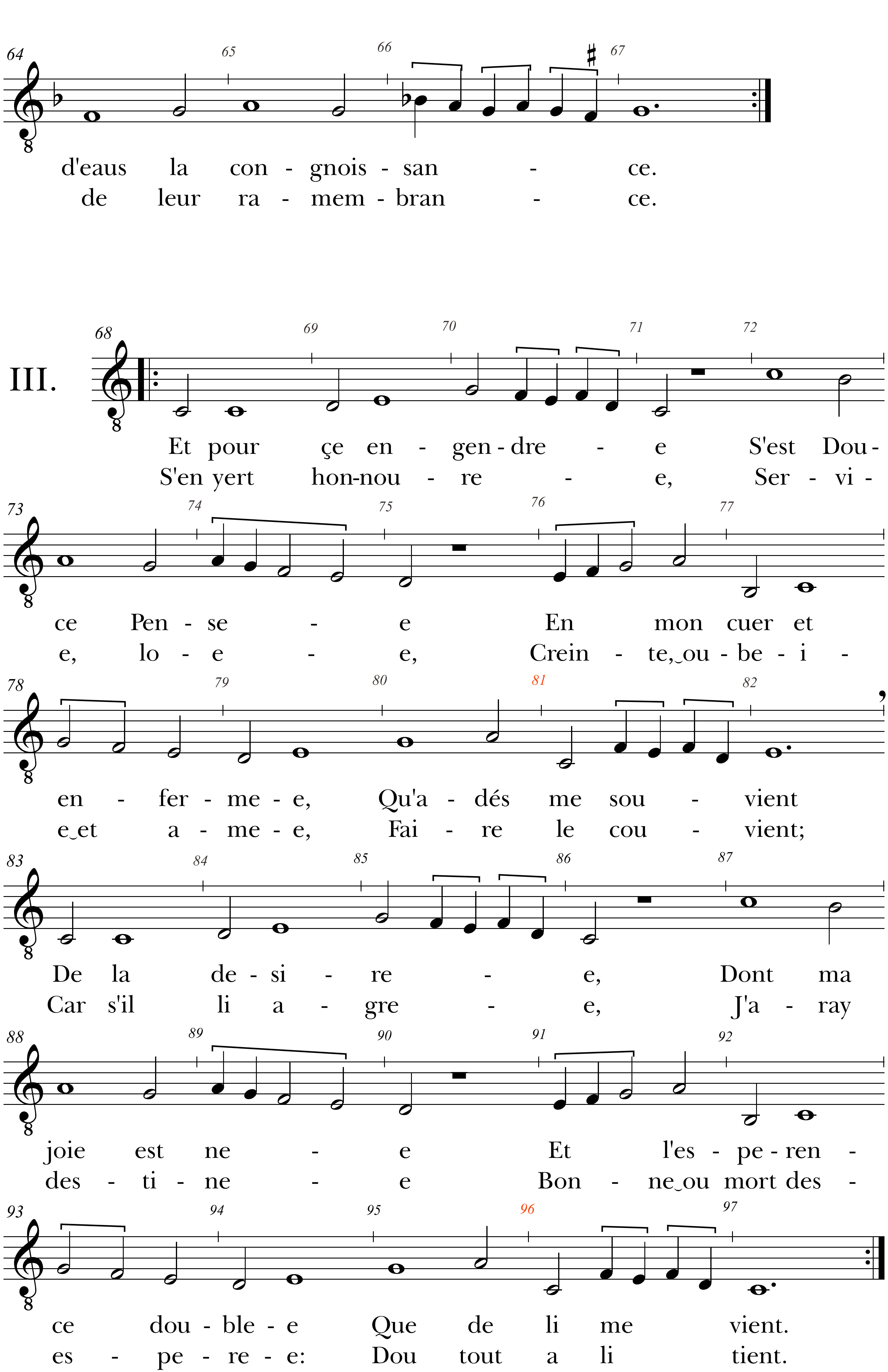

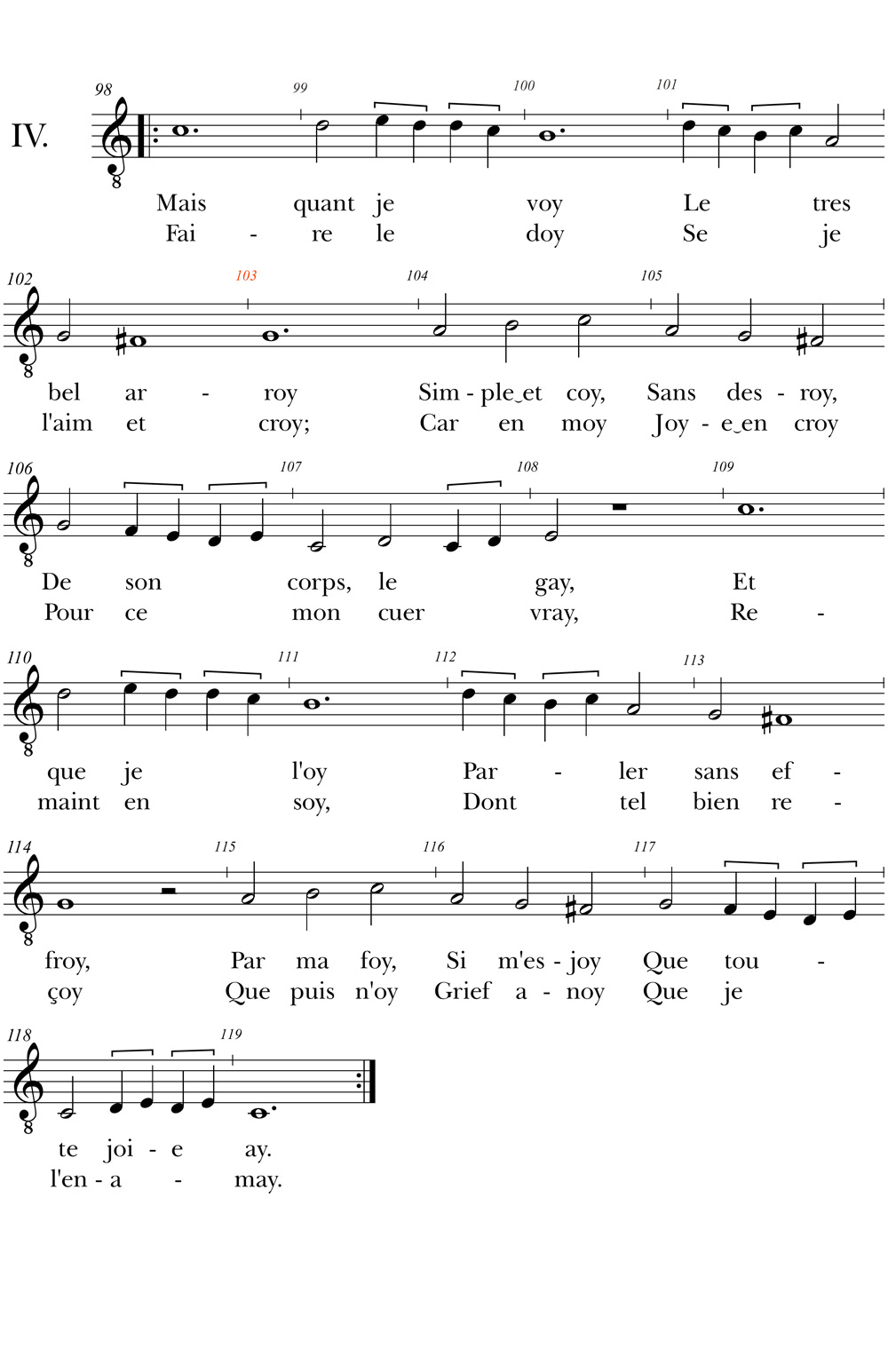

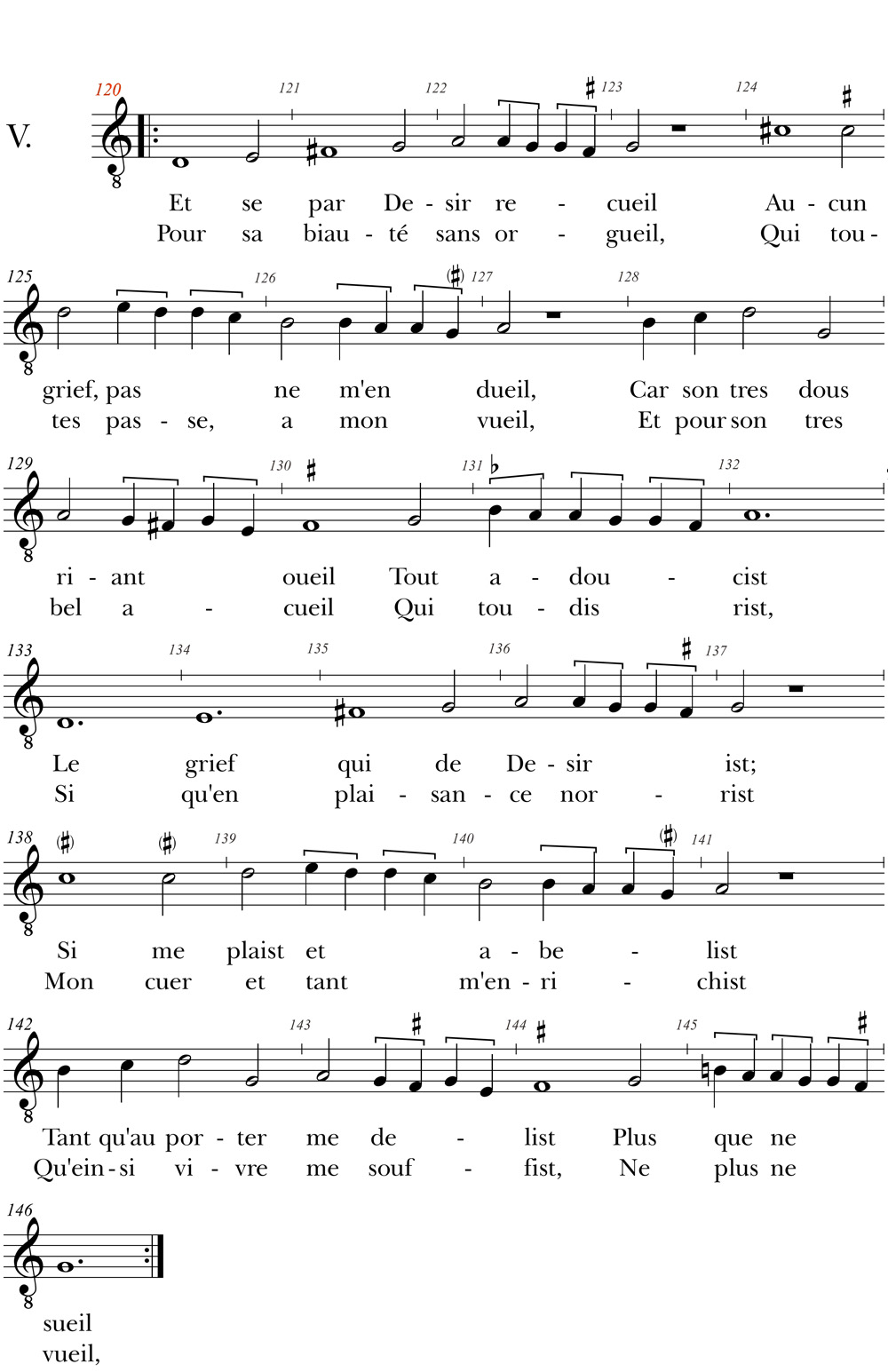

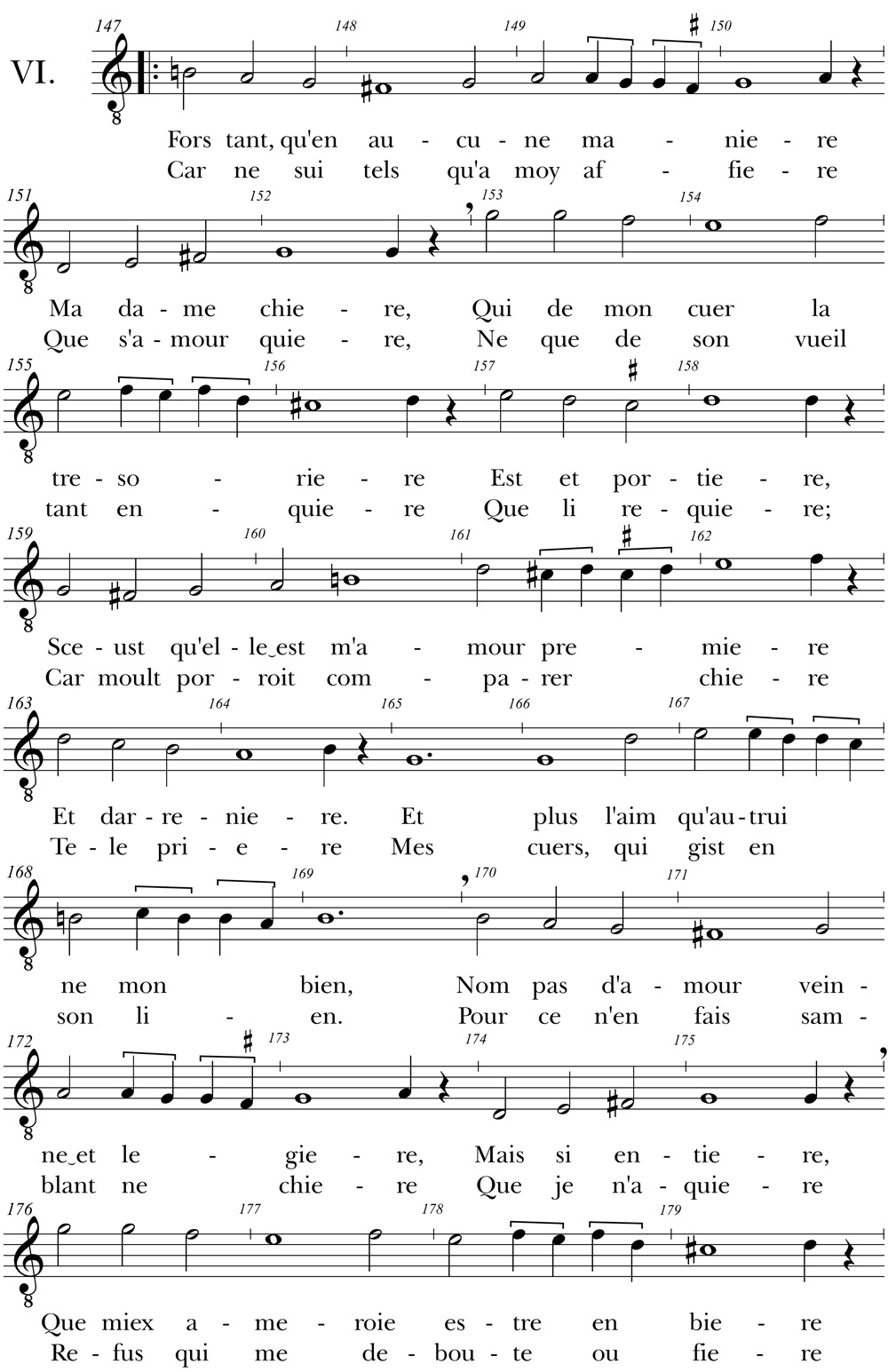

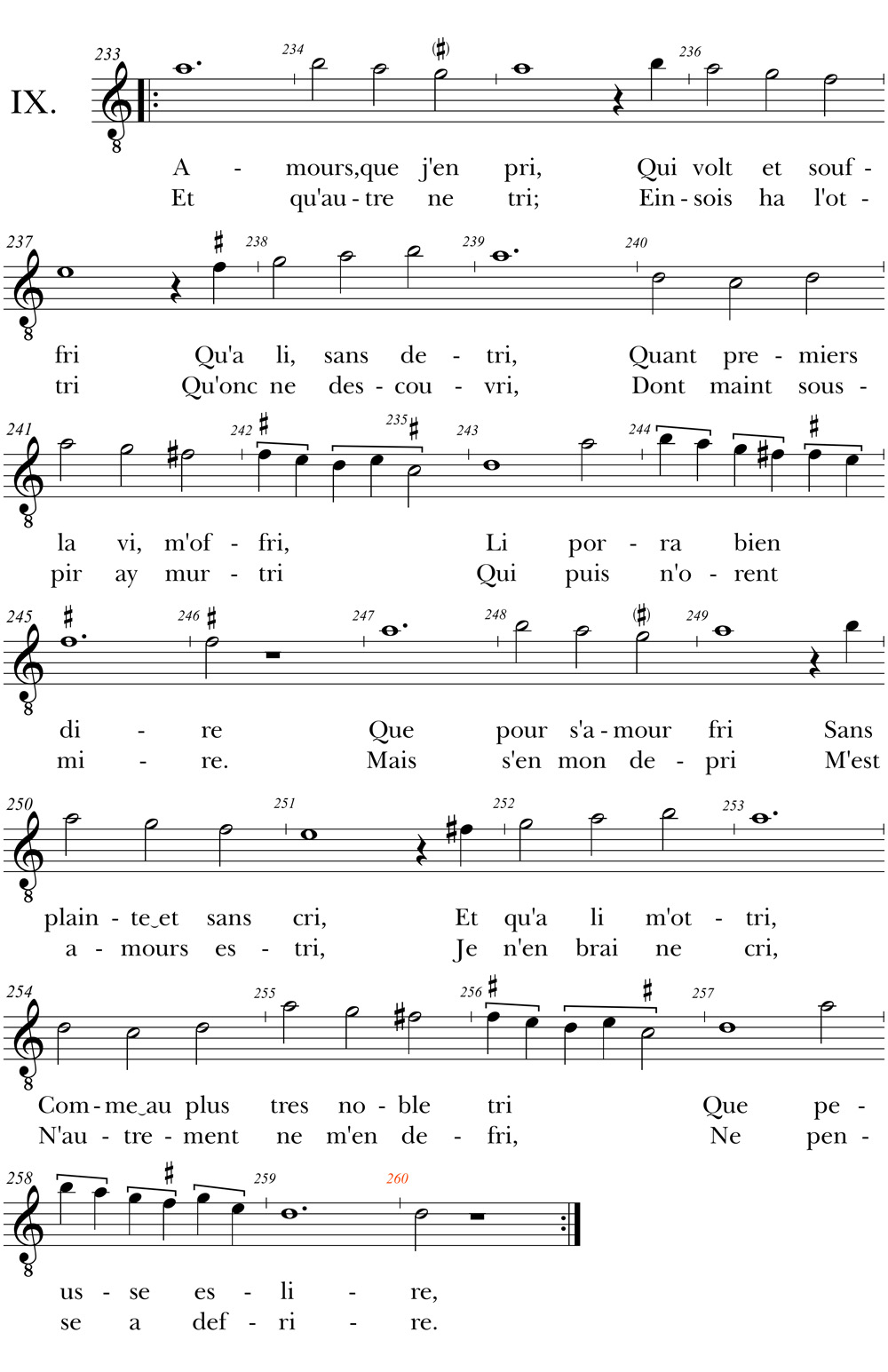

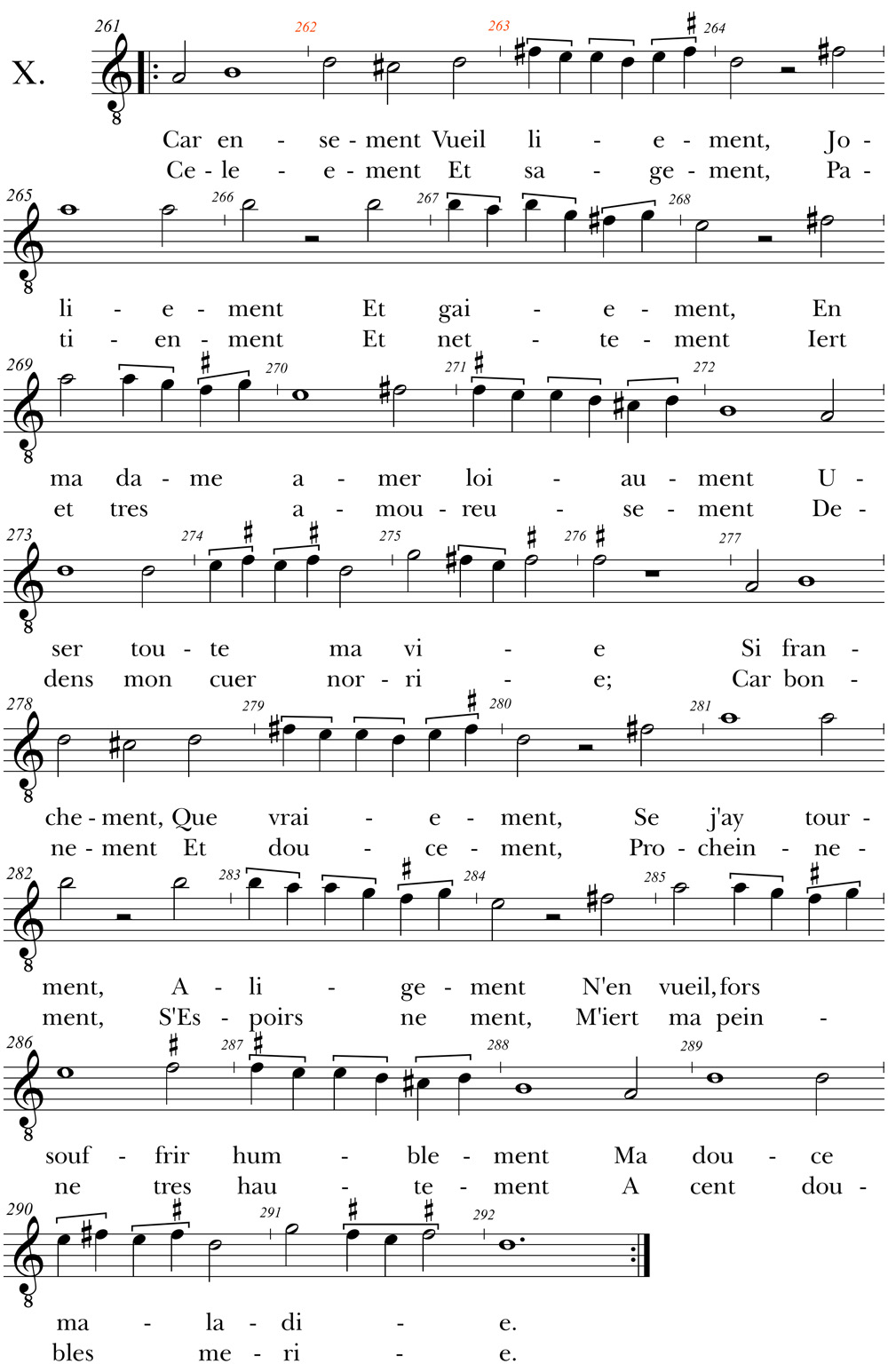

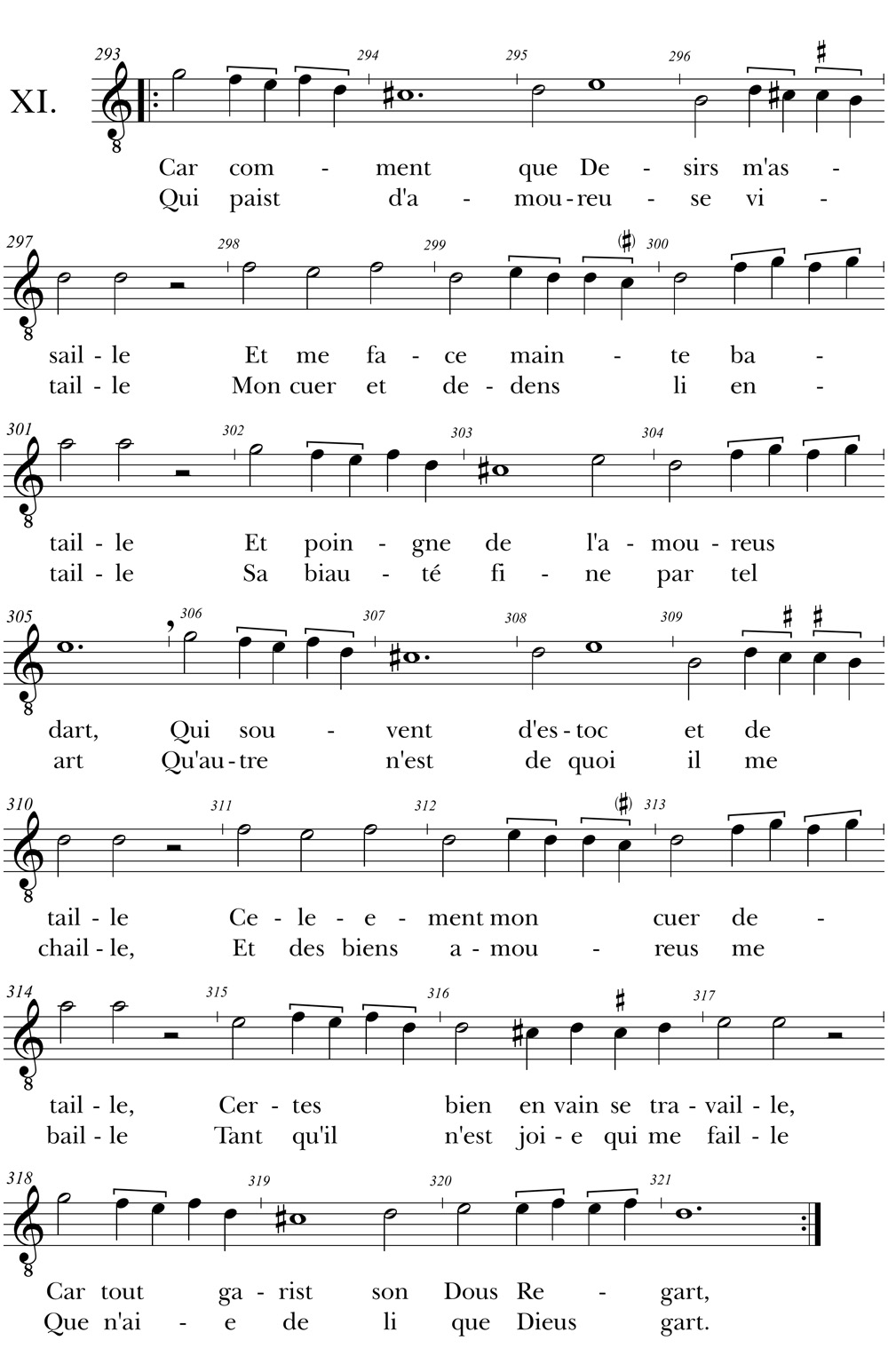

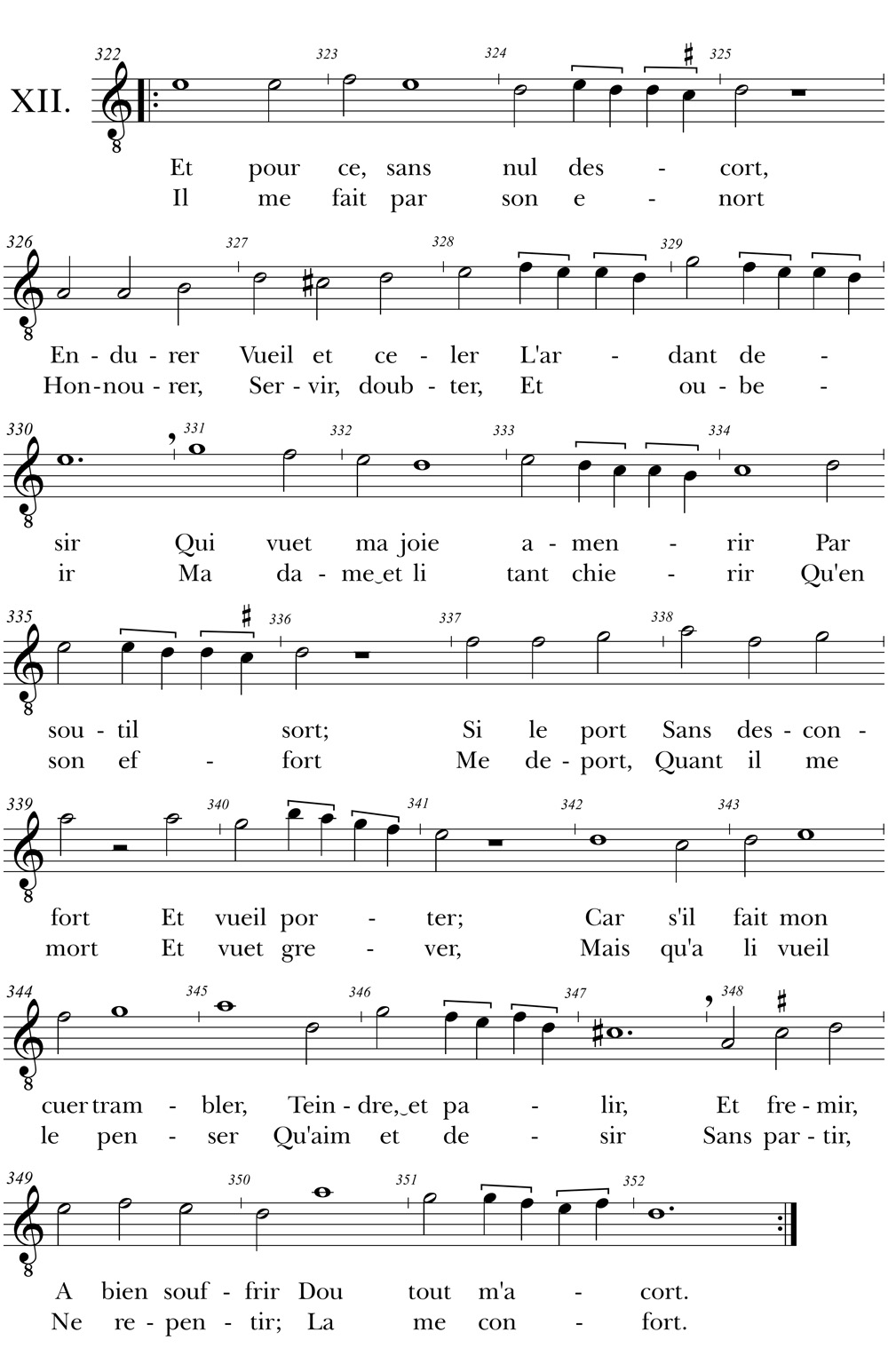

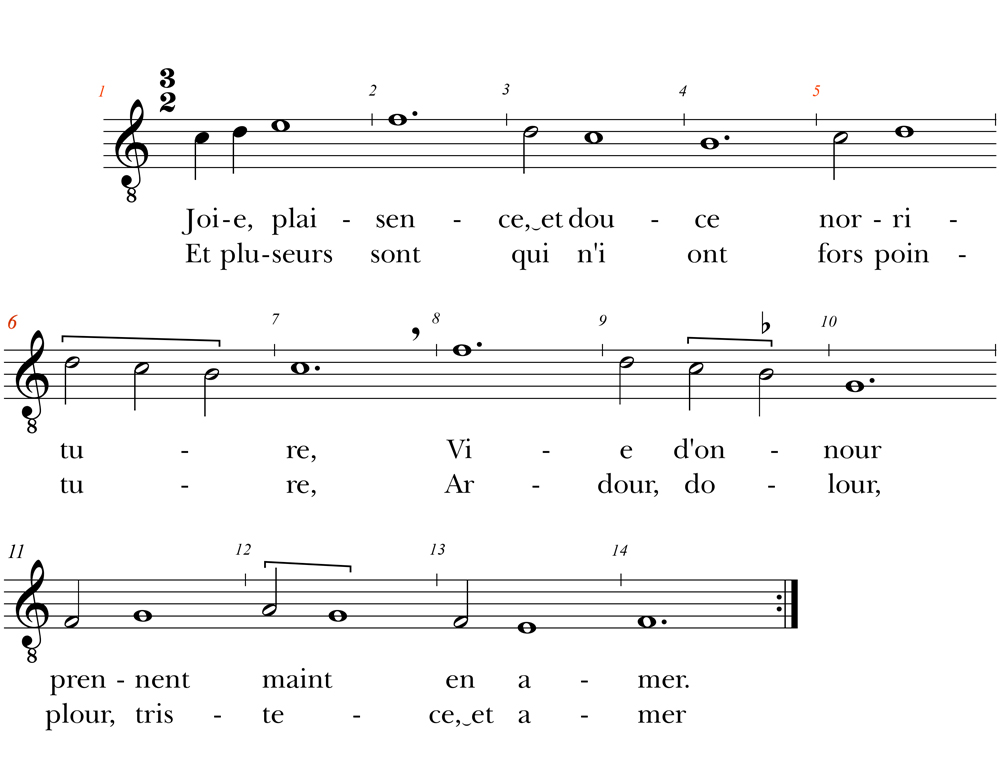

431–680 Qui n’aroit autre . . . . la me confort. The intercalated lyric here is a lay, the most complex and in general one of the lengthier of the so-called formes fixes, the types of lyric verse that by Machaut’s time had become more or less standardized. This poem has twelve sections of irregular length, each of which divides into contrasting halves and has an unrepeated rhyme and metrical scheme (except for the first and last, which are identical). For more, see the Notes on the Music, pp. 555–58.

433–454 Fors Dous Penser . . . . son dous regarder. The allegorical figures — Dous Penser (Sweet Thought), Souvenir (Memory), Espoir (Hope), and Dous Regard (Sweet Regard) — in this passage are all drawn from the RR lines 2601–2734.

465–66 S’Amours tant chier / L’a que fichier. In classical myth, and later in the Middle Ages, Cupid (Greek Eros) is traditionally associated with Venus (Greek Aphrodite). Cupid shoots the arrow or desire into lovers, infecting them with the pleasant wound or malady of love.

647–48 dedens li entaille / Sa biauté fine par tel art. According to Eric Jager, “[t]he lover’s heart marked by his lady’s image was something of a commonplace” (Book of the Heart, pp. 69–70). In the troubadour and courtly love traditions, the heart took on the qualities of a text, able to be imprinted by images and words. His description of the phenomenon seems appropriate for Machaut’s lover: “the heart [was] imagined . . . in pictorial terms as a secular altar devoted to the memory of an earthly Madonna and decorated with her image” (Book of the Heart, p. 70). See also lines 2939–46 and the corresponding note below.

682 Ce lay qu’oÿ m’avez retraire. Here, Machaut blurs the boundaries between written texts and spoken texts. Laurence de Looze argues that “writing enables the poet to appropriate the discourse of lyric orality while dwelling in a world of temporal scripture . . . . A written text is passed off as oral utterance, the hand in effect eliding and replacing the mouth” (Pseudo-Autobiography, p. 86). Also discussing the dislocation which Machaut engineers in this section, Kevin Brownlee points to the way that the lay is offset by the term “lay” in the lines immediately preceding and proceeding the lyric (lines 430, 682). As well as specifically identifying the piece’s genre, “the tense structure of this frame suggests a conflation of two temporalities: the time in which the lay was composed and the time in which it was performed” (Brownlee, “Lyric Anthology,” p. 3).

704–70 Je n’eüsse dit . . . . qui ne ment. In this section, we see the “disjunction between the successful lover of the RR tradition and the faltering, cowardly, and cerebral men who populate his [Machaut’s] writings. These unlikely lovers must inevitably confront their failure to match up to the ideal, but Machaut offers them an alternative realm in which they may thrive” (McGrady, “Guillaume de Machaut,” p. 111). Compare the isolation of the poet here with the lonely garden he finds in lines 797–807.

710–12 L’amoureus mal . . . . les .v. sens. The poet has been deprived of all his faculties, a symptom of his lovesickness, but also a signal of the text’s engagement with CP, which begins with Boethius wallowing in self-pity and despair, thus making it impossible for him to think clearly until Lady Philosophy, noticing his crisis, appears in order to be his intellectual physician.

770 Roy qui ne ment. This game is mentioned in a number of texts from the thirteenth and fourteenth century. However each account differs in so many particulars that it is difficult to untangle a set of rules, leading some scholars to conclude that it may have been played in a variety of different ways. Played by young aristocrats — both male and female — one of the objects of the game seems to be the election of a pair of lovers who are asked a number of questions concerning love and courtship in general, or about their own personal experiences and feelings. In an extended discussion, Richard Firth Green describes the game as “stylized flirtation and erotic sparring” and argues that the purpose of the game was to provide “an acceptable vehicle for bringing young people of both sexes together and allowing them a degree of social, even sexual, intimacy” (“Aristocratic Courtship,” p. 213). On this game see Hœpffner, “Frage-und Antwortspiele.” It should be noted that the game is being played off-stage at the same time as the narrator is reading his love poem to the lady. William Calin suggests that this underscores the fact that “[a]lthough the youth has learned some of love’s theory and expressed his passion eloquently enough in the lay, he fails miserably when forced to act in the real world, indeed makes a total fool of himself” (Calin, Poet at the Fountain, p. 67). This juxtaposition also throws into relief some of the central questions of the text.

786 le Parc de Hedin. The huge 2000 acre Park of Hesdin in northern France, created by Robert of Artois in 1288, rivaled the great royal parks at Clarendon and Woodstock in England, founded by Henry I. These English parks could entertain 200 to 400 guests with features like “a menagerie, aviaries, fishponds, beautiful orchards, an enclosed garden named Le Petit Paradis, and facilities for tournaments. The guests were . . . beckoned across a bridge by animated rope-operated monkey statues (kitted up each year with fresh badger-fur coats) to a banqueting pavilion which was set amongst pools. The monkeys and the water-operated automata, although designed by a Frenchman, were perhaps based on the intricate automata known from Arab writings, and bring us back to the elusive Eastern origin of the idea of the park” (Landsberg, Medieval Garden, pp. 22–23).

799 un petit guichet. The small wicket that Machaut’s protagonist enters is perhaps the inspiration for the “wicket” at the end of part 1 of Chaucer’s House of Fame, which his Geoffrey squeezes through in hope of finding “any stiryng man / That may me telle where I am” (lines 478–79). But unlike Machaut’s protagonist who finds himself in a splendid garden of delight, Chaucer’s Geoffrey is confronted by “the desert of Lybye” (HF, line 488), a “large feld . . . Withouten toun, or hous, or tree, / Or bush, or grass, or eryd lond”(lines 482–85).

883–96 Car selonc ce . . . . come a destruction. Machaut here presents a general and thoroughly conventional image of Fortune, derived first-hand from CP 2 and, at second hand, from RR lines 3950–57. In the passages to follow, more specific references to books 1 and 2 of CP will be noted. For context and analysis of the poet’s use of Boethius see the General Introduction, pp. 20–35. For details on the conventional depiction of Fortune, see Patch, Tradition of Boethius.

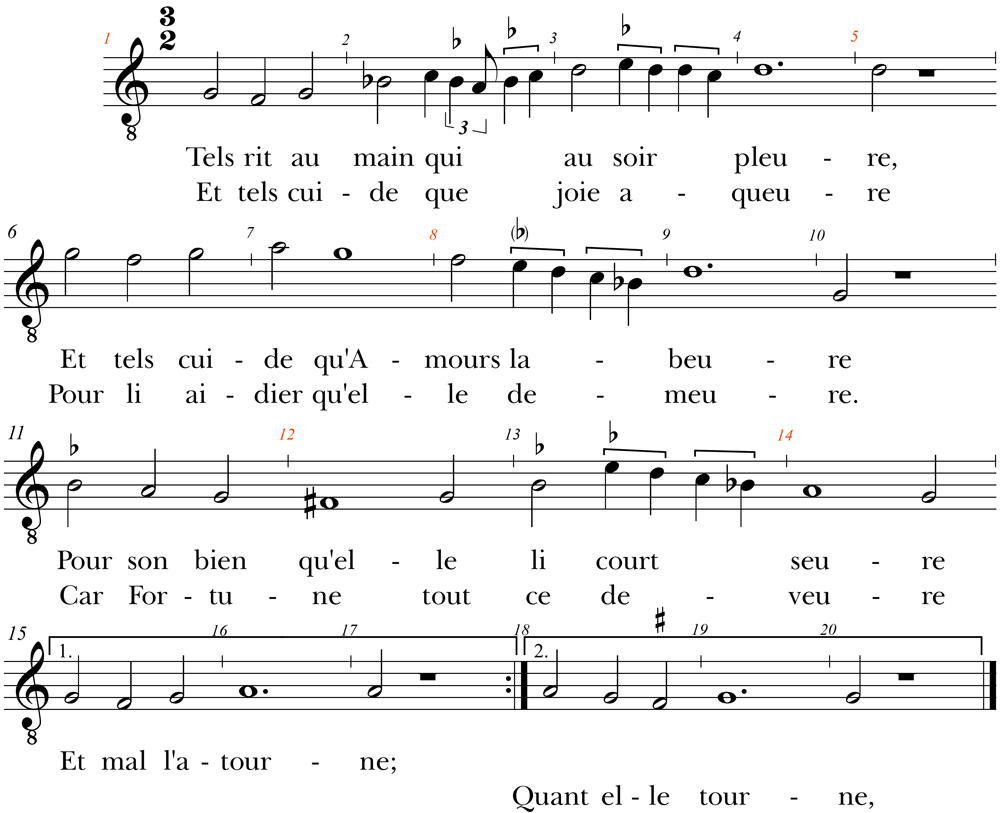

905–1480 Tels rit . . . . Vueil rendre l’ame. The lover’s complainte (complaint) is modeled in general on two passages in CP: 1.m1 and 1.pr4. Boethius’ detailed indictment of his unmerited ill luck, in that second passage, follows the appearance of Lady Philosophy and is in response to her questioning about his despairing state of mind. She comes to aid her acolyte after his brief poetic lament, which begins the work and was, as Boethius reveals, composed under the influence of Muses whom Philosophy chases away. Similarly, Esperence (Hope) appears to console the lover here after hearing his complaint. Machaut gives the impression that the complainte is one of the standard formes fixes, but this seems not to be the case. The complaint here includes 36 stanzas of sixteen lines each. As with the lay that precedes it, the poet text is supplied with a musical setting. For further details see the Notes to the Music, pp. 558–59.

969–73 ij. seaus en . . . . L’autre descent. Proverbial. See Whiting B575.

982–84 Mais Boëces si . . . . De ses annuis. Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (477–524) was a member of the senatorial class who was active in the politics of Rome after the city fell to the Ostrogoths in 493. As he tells the story in the Consolation of Philosophy, his most famous work, Boethius fell victim to a series of palace intrigues, was imprisoned by the Ostrogothic emperor Theodoric the Great, and eventually executed, with treason being the most serious of trumped-up charges. In the centuries following his death, the CP became the most revered and quoted text, except for the Bible, and this is even more surprising since even though Boethius himself was a Christian, there is no mention of Christian theology or doctrine. Instead, Boethius relies on an elaborate and persuasive synthesis of ideas gleaned from Aristotle and Plato, and also the Stoic thinkers who had gained a place of honor in late Roman culture. His theme is the meaning of unmerited misfortune, and the ways in which such tragedy is actually a blessing in disguise for those who would value what is of the highest good in human experience. The beauty and intellectual force of the work exerted a lasting appeal on western culture until the beginning of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century. Chaucer and Jean de Meun (one of the two authors of the Romance of the Rose), produced translations in English and French; other English translators were the Anglo-Saxon King Alfred and Queen Elizabeth I. The General Introduction (pp. 20–35) includes a detailed discussion of the Boethian material in the Remede.

1001–1112 Nabugodonosor figure . . . . d’un seul assaut. This passage on the dream of Nebuchadnezzar is drawn from Daniel 2:31–45, which includes both a description of the statue from the king’s dream and the prophet’s interpretation of it, which emphasizes the succession of earthly kingdoms, all of which will be displaced and eventually destroyed, to be succeeded by the kingdom of God. Machaut adapts this material, with an emphasis on Daniel’s subsequent career, in the Confort lines 436–480. Machaut seems to have invented the elaborate allegorization of the statue presented here. Gower uses the same passage to illustrate the unreliable mutability of Time (CA, Prol, lines 585–624). Machaut handles this tale a bit differently from both the Old Testament and Gower’s version by explicitly identifying Fortune as the culprit from the beginning.

1191 Eschat et mat. Fortune as a chess player is conventional. See Chaucer, BD, lines 618–661.

1311 Seneques. Roman culture boasted of two writers named Seneca, members of the same clan (gens). Better known to modern literary and intellectual culture is Lucius Anneaus Seneca (4 BCE–65 CE), known as Seneca the Younger, who made a reputation as a moral philosopher who popularized Stoicism and as a writer of “closet drama” tragedies. In this passage, Machaut is undoubtedly referring to his father, Marcus Annaeus Seneca (54 BCE–39 CE), generally known as Seneca the Rhetorician, whose major work, a multi-volume study of imaginary law cases (Controversiae), the presentation of which involved rhetorical issues, was known in part to the Middle Ages and served as what we would now call a university text for the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, and logic).

1346 Cuer, corps, ame, vie, et entente. Compare Chaucer, BD: “With good wille, body, herte, and al” (lines 116 and 768).

1468 medecine. In CP Lady Philosophy functions, as she herself describes, as the physician who will heal the suffering Boethius; the medicine she provides him with is a series of arguments. It is their dialogue that provides his cure. In the Remede, on the other hand, Esperence, while providing a similar kind of intellectual medicine, can only prepare the lover to receive what will ultimately cure him: the acceptance by his lady of his love suit and her reciprocation of the affection he bears her.

1502–03 Mais je vi seoir . . . . la plus bele dame. The advent of Esperence, and her otherworldly quality, mirrors closely the corresponding passage devoted to Philosophy, who, as previously noted, appears to Boethius after listening to his self-pitying complaint in the first meter. As discussed at length in the General Introduction, Esperence speaks to the traditional trajectory of this love poem, which traces the lover’s suffering and sorrows, his encounter with the woman previously loved from afar, and the pseudo-marriage that cements their relationship under the auspices of Esperence and Amours. Philosophy, of course, plays a quite different role in the CP. Her task is to not to help Boethius recover what he has lost (wealth, freedom, and reputation), but rather to help him understand that he has not lost what matters most — himself and his unfettered mental pursuit of the highest good. The CP concludes not with a happy scene of reconciliation and restoration, but with an elaborate meditation on the most relevant of metaphysical and existential facts: that men, inhabiting a divinely ordained universe, nevertheless possess that most precious of gifts, a free will.

1519–26 Si clerement resplendissoit . . . seur mon visage. Compare CP 1.m3.1–2.

1533–39 Car tout aussi . . . . sa clarté premiere. Machaut’s elaborate simile is remarkably precise regarding cataract surgery. This catches a modern reader off guard, given that the first successful cataract surgery, by modern standards, was not performed until 1748, by the French surgeon Jacques Daviel. But recorded efforts at dealing with cataracts go back as far as a Sanskrit manuscript c. 800 BCE, in which an Indian physician named Maharshi Sushruta devised a system subsequently called “couching” that was performed with occasional success and remained in practice in some countries even into modern times. If Machaut knew of needle and thread removal or variations on couching practices, whereby a film (“une toie,” line 1537) that impeded sight was “subtly” removed to restore clearer vision, such practices must have been based on Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c. 29 CE) in his De medicina, 7.7.10–15. See On Medicine, trans. Spencer, vol. 3, which discusses use of needles and threads to lift and break up the cataract, or to “couch” the pupil into the vitreous area of the eye to let in light. Spencer includes diagrams of equipment and procedures for couching or cataract removal (3:651). But, perhaps, if we think metaphorically within Machaut’s simile, and imagine the lover’s self-pity and floods of tears to be cataracts, then it may be that Lady Philosophy in the guise of Dame Esperence, is the surgeon who removes the veil of blinding tears as he beholds the beauty of his lady. Compare CP 1.pr2.16–18.

1540–76 Tout einsi me . . . . savoir ma maladie. As part of her cure, Esperence restores both memory and sight to the narrator, which then activates each of his other senses that have been compromised since lines 710–12 (see note above). Smell is evoked from her fragrance (lines 1544–56), with touch following as she takes his hand into her own (lines 1574–75), hearing as she speaks to him, and finally speech (line 2123).

1544–58 un odeur . . . . je ne die. More than Lady Philosophy, Esperence is imagined as a beautiful woman, an appropriate stand-in for the poet’s lady in their early dialogue on his experience of love. One of her conventional attributes as the proper object of refined admiration and affection is her sweetness, here elaborated in terms of the savor of her presence, which is like a balm possessing healing powers.

1567–78 Mais nulle reins . . . . et veinne. Compare CP 1.pr2.9–11. It is typical of Machaut’s approach that he picks out from his source one of its most poignant details. Philosophy, at first unable to get the stupefied Boethius to speak, puts her hand on his chest in a manner that is both maternal and appropriate for the physician she claims to be. Adopting a softer tone, she pronounces him not stupefied but lethargic. Machaut’s version extends the physician trope, as Esperence takes the lover’s pulse. See especially lines 1603–04.

1585–1607 Et quant elle . . . . elle m’ot sentu. The identification of the beloved as a physician who can cure the male lover’s need is commonplace. It may be of interest, nonetheless, to know that there were women physicians.

1682–91 Franchise et Pité . . . . Charité et d’Umblesse. These RR-like allegorical figures represent aspects of the lady’s character. Compare to those in JRB and JRN. See also the note to lines 433–54 above.

1780–84 Ne riens ne . . . . blanches, rouges, jaunes, ou perses. Esperence describes these colors as inimitable signs of love. Colors are commonly used metaphorically by medieval writers. With regard to love, white usually designates innocence and purity; red denotes passion, emotive love, and the heart; yellow suggests radiance like the sun, joy, and fair welcome; while blue, the Virgin Mary’s color, connotes higher love and fidelity (see Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art, pp. 151–53.) But as Ferguson also attests, colors may — when used with counterfeit intent — thereby suggest their opposites: white might imply hypocrisy; yellow, changeability, dissembling, or false behavior; and red, hatred, vengeance, and anger. These latter possibilities do not apply here, of course, given the lover’s sincerity. Compare lines 735–40, where poet does not want to lie to his lady. Machaut will further develop this theme of colors in his discussion of love’s heraldry (lines 1901–10).

1810–14 Homs ne diroit . . . . il se duet. This section describes one of the central concerns of the poem: it is a key element of medieval love lore that love suffering is inherently paradoxical. As Sarah Kay writes,“its only true expression is the one that cannot be expressed.” The poet needs to be able to suffer in order to give his work range and virtuosity, but not so much that it silences him (Kay, “Consolation, Philosophy and Poetry,” p. 35). See the opening and closing stanzas of the lay (lines 431–58 and 653–80) and Esperence’s chanson roial (especially lines 1987–93) for a further articulation of this theme.

1901–10 ces couleurs . . . . c’est fausseté. On the various colors and their function in medieval erotic lore, see Wimsatt, “Machaut and Chaucer’s Love Lyrics.” See also the note to lines 1780–84 above.

1950 Que de toy ci dessus propos. Esperence makes reference to what she had previously said as if it were a written text “here above.” Such frame-breaking metafictional gestures, which call attention to the status of this dramatic encounter as part of a written text, are not uncommon in Machaut’s poetry. See Palmer, “The Metafictional Machaut” for further discussion.

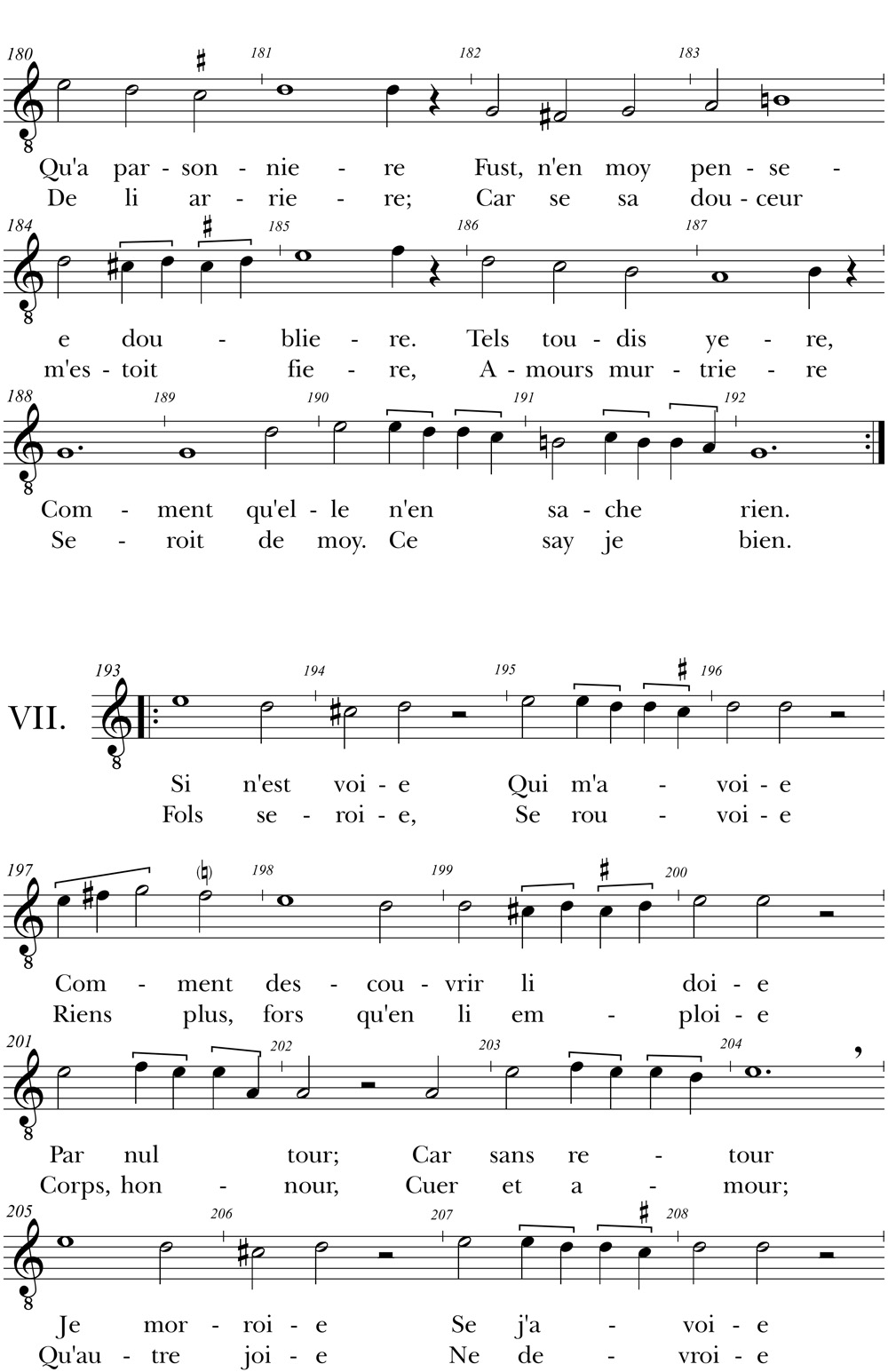

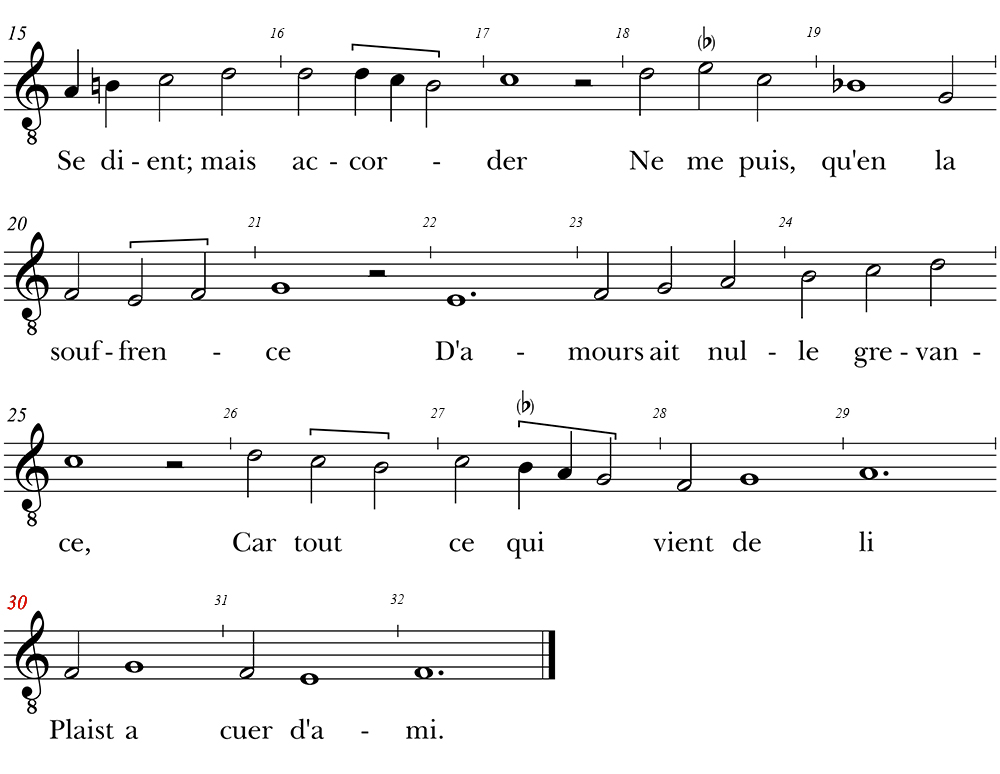

1985–2032 Joie, plaisence . . . . qui t’ont servi. The prosimetric form of CP suited Machaut’s aesthetic interests perfectly, as can be seen from his use of intercalated lyrics in his other dits where there is otherwise no Boethian influence. So it is impossible to say whether the chanson roial sung here by Esperence to the lover finds its source in similar lyrics (e.g., 1.m2) sung by Philosophy to Boethius. The chanson roial here consists of five stanzas with identical rhymes, each concluded by an envoy. It bears remarking that this lyric is much simpler, both formally and intellectually, than the lay and the complainte that precede it.

2039–2093 Comment t’est . . . . faire le doi. Compare CP 1.pr2 and 1.pr4.1–7.

2089 Et le fer chaut, on le doit batre. Proverbial. See Hassell F51.

2094 un anel. When Esperence lovingly gives the poet a ring, she provides a talisman of reassurance to protect him as long as he is faithful to her.

2151 Je sui li confors des amans. In her discussion of the Remede as a re-write of Boethius’ CP, Sarah Kay notes that Esperence “seeks to console rather than redress or punish the sufferer” (Kay, “Consolation, Philosophy and Poetry,” p. 32). Just as in Confort, she sympathizes with the lover, defending and protecting him from misfortune and assisting him in the courtship of his lady. As she observes, “[d]espite its title . . . the lexis of consolation is remarkably absent from Boethius’ text” (p. 22).

2173–77 Je les norri . . . . je les honneure. Compare CP 1.pr2.1–7.

2209 de la couleur d’une panthere. Jeremiah 13:23 is a possible source for this comment about the panther’s spots.

2317–18 En bien nombrer . . . . Pytagoras et Musique. Music and Arithmetic were two of the four subjects (the so-called Quadrivium) that formed the second part of the medieval university curriculum.

2318 Pytagoras. Pythagoras, a sixth-century Greek mathematician, famous for the “geometric theorem that still bears his name” (OCD, p. 1283–84).

2319 Michalus et Milesius. The two intellectual worthies mentioned here are, respectively, Michaelis Psellos, a Byzantine monk (fl. 1050) famed for his learning and author of numerous treatises devoted to such topics as medicine, astronomy, and history, which were translated into Latin and made available in Western Europe; and Thales of Milet (Thales Miletius in medieval Latin; fl. 575 BCE), the founder of a noted school of Greek philosophy and — like Psellos — a formidable polymath.

2320 Orpheüs. In Greek myth, Orpheus was a legendary singer, son of the god Apollo and a Muse, “whose song has more than human power” (OCD, p. 1078). Machaut tells the tale of Orpheus and his wife Eurydice in the Confort, lines 2277–84.

2348 ff. Mais je vous . . . . Here the narrator takes a more active role in the conversation. His more open engagement of Dame Esperence demonstrates more vigorous health, even as he asks how he should conduct himself in order to restore his welfare.

2403–2856 Biaus dous amis . . . . qui li nuise. Dame Esperence, like Lady Philosophy, reassures her patient with a disquisition on Fortune with her two faces (line 2408) and her bitter/sweet ways. Compare CP 2.pr1.33–34, which refers to Fortune’s two faces, a commonplace of medieval ideas about Fortune’s essential duplicity. See Patch, Goddess Fortuna for further details. Esperence uses key Boethian tropes of anxiety, such as surging waves (lines 2564–70, 2663–70) or indebtedness (lines 2639–42) to depict emotional turmoil, as part of his therapeutic process. She blames the lover for trusting in Fortune (lines 2560–62), which makes him a slave to her fickle ways. Ultimately, she proposes that Love, when ruled by Reason, is a viable alternative to trusting Fortune.

2467–73 La bonneürté souvereinne . . . . cil de Fortune. This passage offers a faithful, if somewhat simplified, version of the key conclusion of Philosophy’s argument about the nature of happiness, namely that the goods of Fortune are rendered insufficient by their inherent instability. As argued in the General Introduction, this central precept (whose ultimate sources are Aristotle and Plato) clashes with the ethos of love poetry, in which the lover always gains the lady’s affection, even though such success can, and often is, reversed when Fortune turns her unpleasant face in his direction. To be sure, the lover can internalize the image of his lady and contemplate her beauty and virtues in his mind, and in this sense love puts itself beyond the vagaries of Fortune. However, the generically correct and emotionally satisfying ending offered in RF depends on the physical union of the lovers, whose presence to one another is the source of ultimate satisfaction.

2489–94 Car bonneürtez vraiement . . . . a .i. estrange. Compare CP 2.pr4.62–66.

2531–40 S’elle estoit toudis . . . . mouvant soit estableté. Compare CP 2.pr1.59–62.

2539–42 Comment que sa mobilité . . . . c’est sa droiture. Compare CP 2.pr2.28–31.

2552–58 Car autant en fait . . . . et en cloister. Compare CP 2.pr2.45–47.

2577–80 Se tu estens . . . . vens la conduira. Compare CP 2.pr1.55–56.

2583–91 Einsi est quis . . . . de ses maisnies. Compare CP 2.pr1.58–59.

2613–27 Qu’a l’issir . . . . de son droit. Compare CP 2.pr2.9–13.

2630–38 Ne t’a . . . . de hui a demain. Compare CP 2.pr2.13–16.

2663–65 Tu vois la mer . . . . pleinne de tourment. Compare CP 2.pr2.25–27.

2675–77 Mais richesse . . . . nuls ne part. Compare CP 2.pr2.17–18.

2685–88 Volentiers! Elle t’a . . . . tu yes sires. Compare CP 2.pr4.27–30.

2702 Qu’aprés le lait il fera bel. Proverbial. See Whiting D417.

2705–07 Et aussi je . . . . maleürté a venir. Compare CP 2.pr1.44–45.

2717–18 Mais en tout . . . la fin des choses. Compare CP 2.pr1.45–47.

2754–55 Je ne di . . . . n’ait assez. Compare CP 2.pr5.44.

2787–90 Bonneürté est . . . . et Souffissance. Compare CP 3.pr.9.81–83.

2791–96 C’est bien . . . . failli onques rien. Compare CP 3.pr10.37–38. Machaut Christianizes his version of the famous passage by substituting the three persons of the Holy Trinity for Boethius’ “most high God.” Dame Esperence borrows this one-in-three and three-in-one idea from Dante’s Paradiso 14.28–30, a Boethian concept that appealed to Chaucer as well a few years later in shaping his conclusion to TC 5.1863–65. Given the three poets’ debts to Boethius, the allusion is most appropriate in Hope’s heavenly apocalyptic vision on the nature of true love. Dante had just placed “l’anima santa” (the soul of Boethius, 10.125) as the eighth of his most revered teachers in the fourth circle of Paradise — the habitation of the sun.

2793 Qui est fin et commancement. This famous passage is from the Book of the Apocalypse 1:8.

2827–32 Se ce n’est . . . . aggreable la pointure. The gaze of the female beloved as a weapon that wounds the male lover is conventional. TC, RR, and CA also describe wounds as an effect of love. See also lines 3320–21 and JRB, explanatory note to lines 409–27. For more on what Suzannah Biernoff calls the “wounding gaze,” see Sight and Embodiment, pp. 48–53.

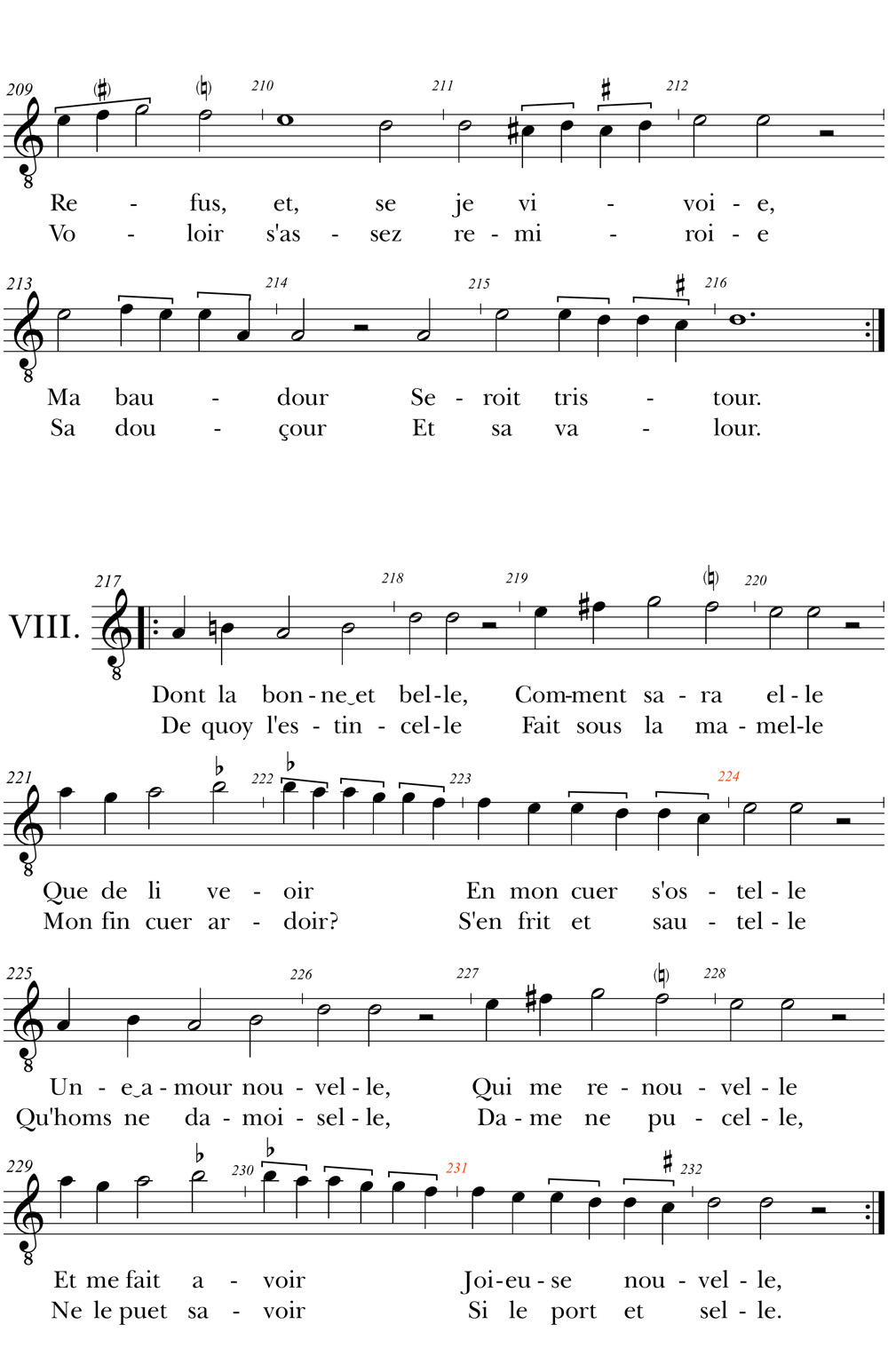

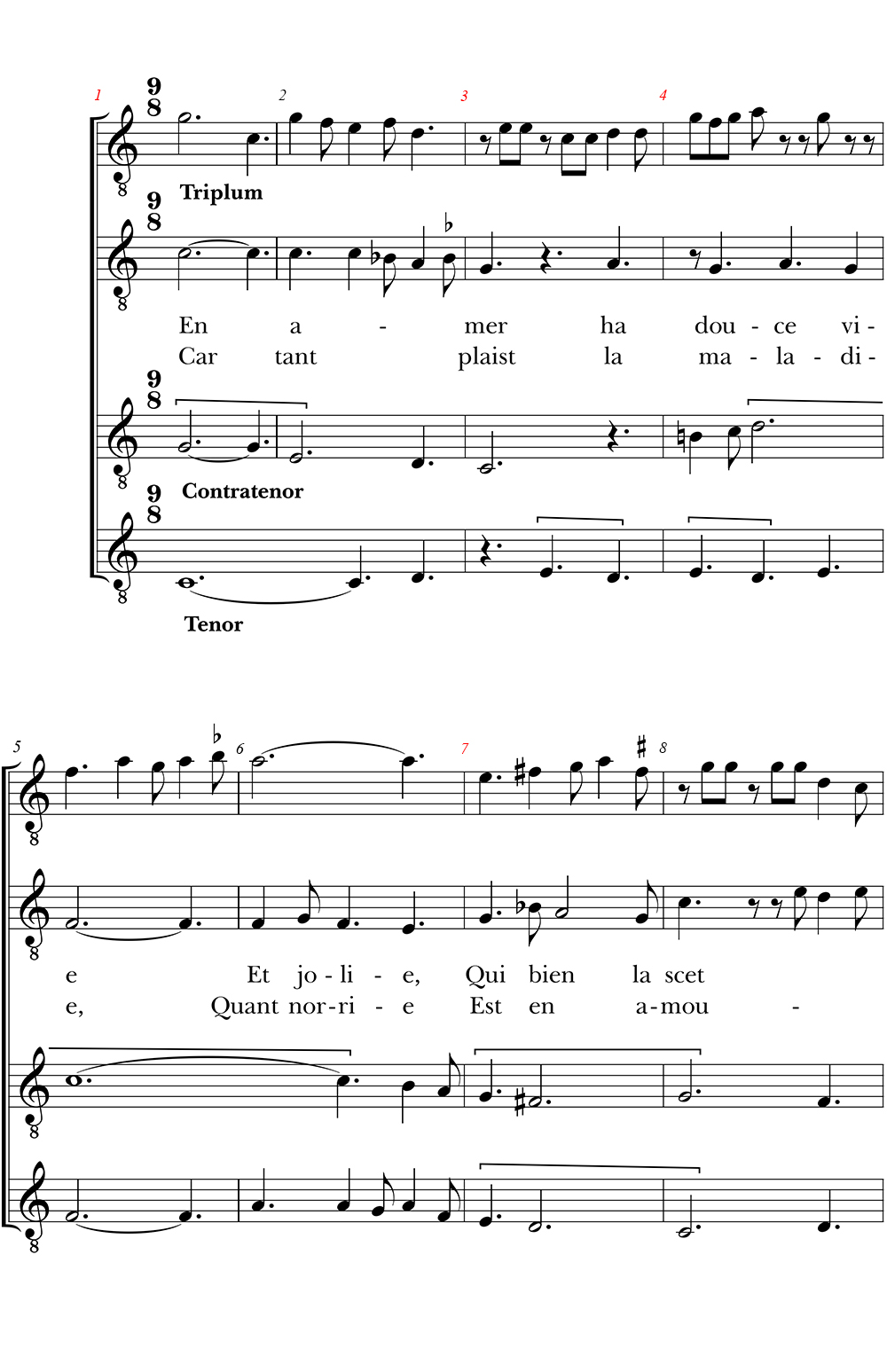

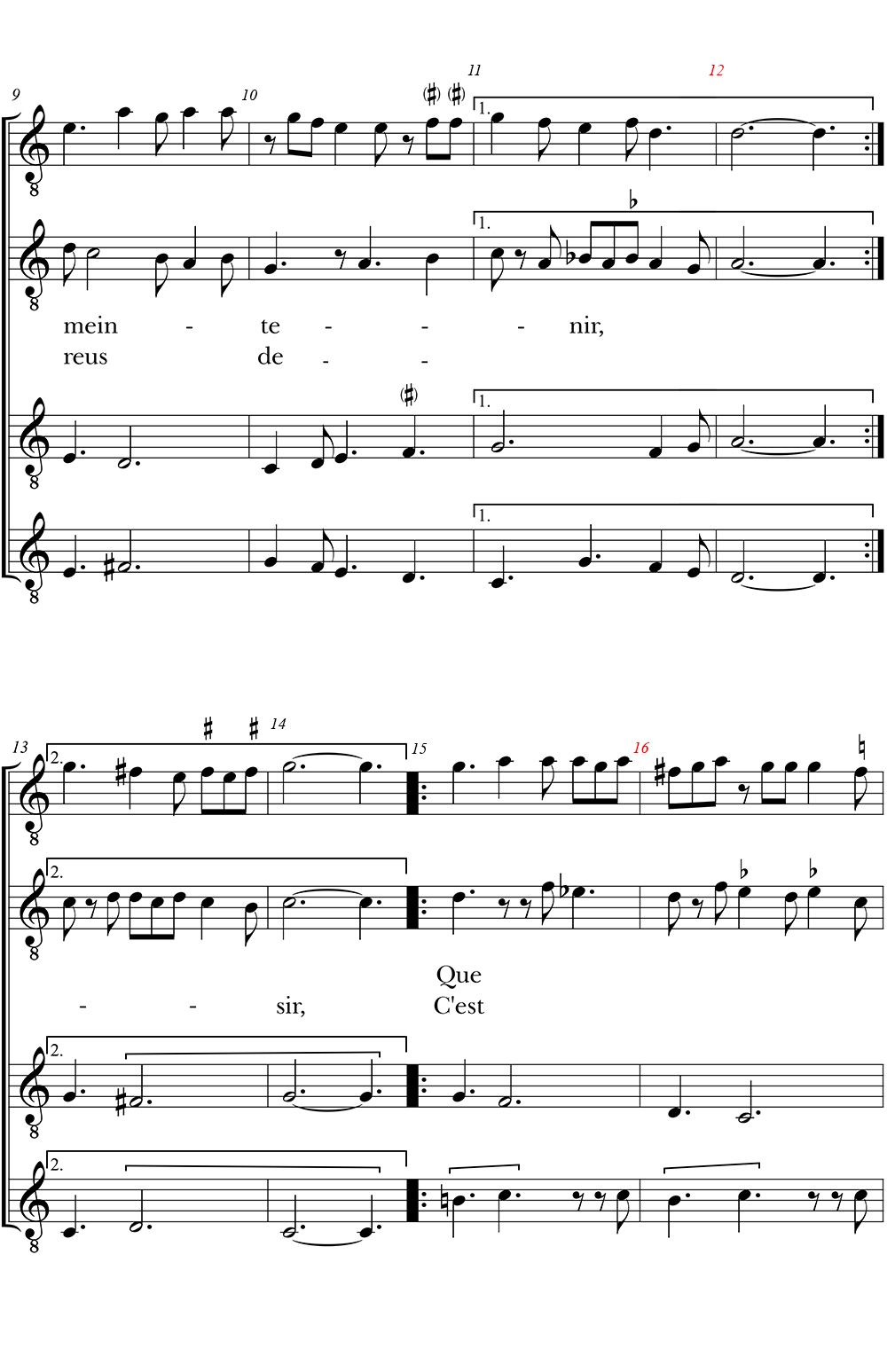

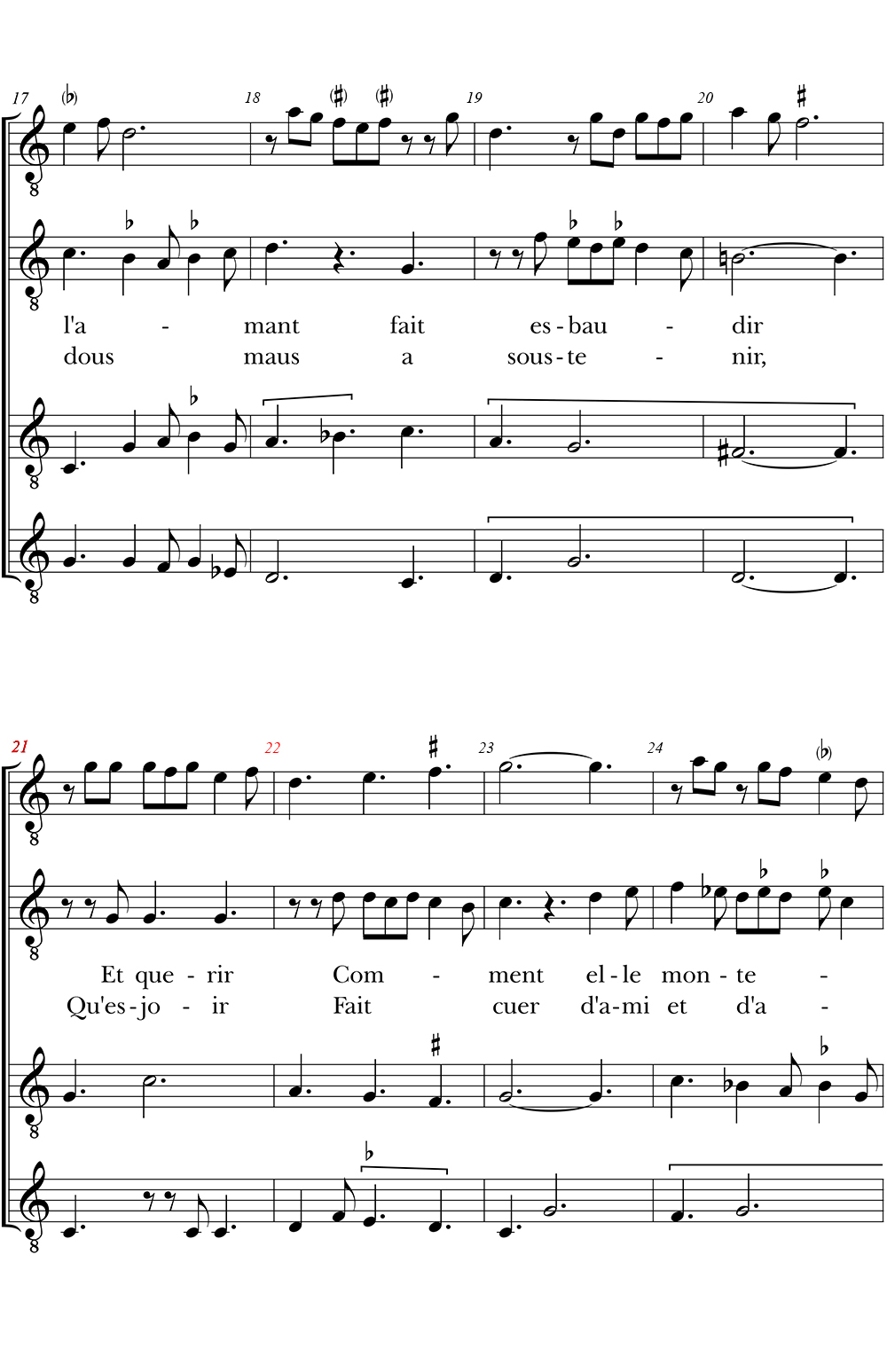

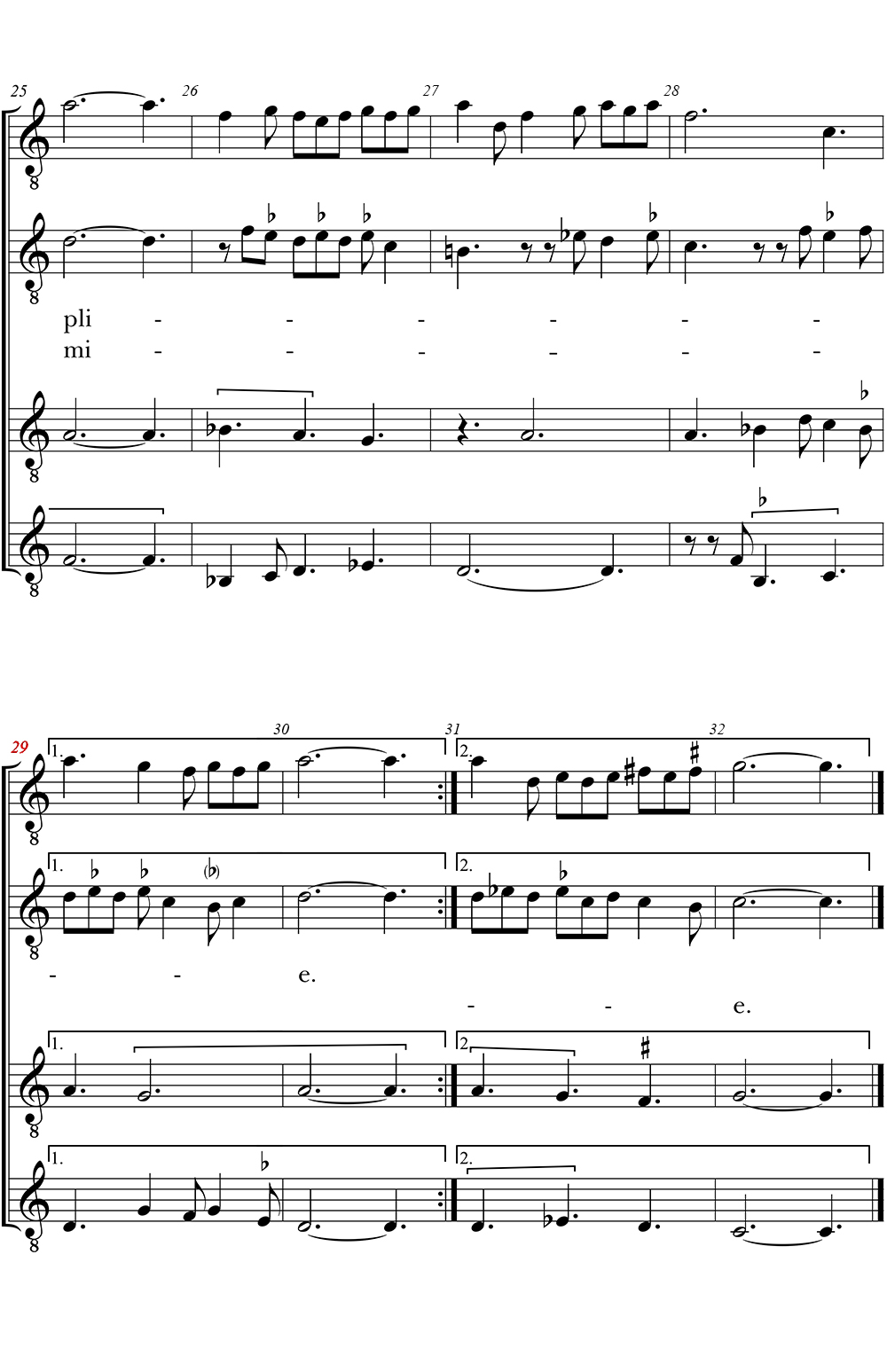

2857–92 En amer ha . . . . et d’amie. The baladelle is a special form of the balade, with stanzas of three parts rather than four. See further the notes to the music (pp. 561–62) and Poirion, Le Poète et le Prince for general commentary on the lyric genres and their subtypes. In this baladelle, Hope exalts love’s anguish over the joy of reciprocation and celebrates the hope of love over its actual realization.

2939–46 Et par maniere . . . . parchemin, n’en cire. The metaphor of memory likened to an inscription on a wax tablet is conventional. For more on the seal-in-wax model, see Mary Carruthers, Book of Memory, pp. 24–25 and 32–33. See also the note to lines 647–48 above.

3021–24 Cils dous espoirs . . . . cuer et resjoïr. Here, the narrator identifies his source of joy as Hope, rather than his lady. It is important to remember that it is Esperence who provides the provisional consolation (the first round of medicine) that enables the lover to seek out, merit through his speech and poetry, the consolation that finally relieves his suffering, which is of course the lady’s acceptance of his suit and her acknowledgment that she reciprocates his love for her.

3046–48 Mais trop durement . . . . riens de m’aventure. Discretion, or keeping love a secret, is a staple of courtly love — often because adulterous love affairs were encouraged. Andreas Capellanus, author of the twelfth-century Art of Courtly Love, advises that “the man who wants to keep his love affair for a long time untroubled should above all things be careful not to let it be known to any outsider, but should keep it hidden from everybody; because when a number of people begin to get wind of such an affair, it ceases to develop naturally and even loses what progress it has already made” (trans. Parry, p. 25). See also lines 3873–77 and 4199–4203.

3170 Qui plus est prés dou feu, plus s’art. Proverbial. See Whiting F193.

3205–3348 Amours . . . . et souffissance. The priere (prayer) uttered by the lover is not one of the conventional formes fixes of medieval lyric, and it is the only intercalated lyric in the poem that is not set to music. For further discussion, see the "Introduction to the Music,” p. 78.

3502–03 Diex, quant venra . . . . que j’aim si. These two lines might well be the refrain to a virelai, as Hœpffner opines (Œuvres de Guillaume de Machaut 2:liii-liv).

3771–72 Demander vient de . . . . löange de courtoisie. Proverbial. See Hassell D22.

3843–46 Mais quant Esperence . . . . de m’amour l’ottroy. After the lover’s confession, the lady grants him love, in the name of Hope, who presides, along with Love, at their exchange of vows and rings.

3891–944 Quant la fumes . . . . grant piessa cornee. This remarkable passage provides a rare account, in all its practical business, of the joy and bustle of preparing a hall for a feast, as people hustle to get the trestles and boards in place, furnish the tables with linens and place settings, wash their hands, cut the bread, clean up the crumbs all the while laughing and chattering in several languages — truly a marvel to witness.

3925–27 François, breton . . . . autre divers langage. An interesting note of realism in the poem is Machaut’s noting of the different languages spoken by the servants and courtiers at his fictional manor house, a diversity that undoubtedly reflects the social reality of the age.

3947 corset. For full discussion of fourteenth-century dress, see Piponnier and Mane, Dress in the Middle Ages.

3963–88 Car je vi . . . . en ce parchet. The catalogue of musical instruments here bears comparison with Machaut’s recycling of this motif in the La Prise d’Alixandre, lines 1147–76. See the forthcoming Volume 6: The Taking of Alexandria of this edition.

3964 Viële, rubebe. According to the Oxford Music Online database, a vielle can refer to various instruments like a “hurdy-gurdy and fiddle” (Oxford Dictionary of Music, “vielle”). A rebec is “a bowed instrument with gut strings, normally with a vaulted back and tapering outline” (Grove Music Online, “rebec”).

3970 Douceinnes. A douçaine is a medieval cylindrical shawm, or woodwind instrument with a double reed (Oxford Companion to Music, “douçaine”).

3975 Buisines. This is a “medieval name for a herald’s trumpet” with a tube over a meter long, with a flared bell, and made of brass or silver. They are “frequently shown bearing the banner of a noble person” (Grove Music Online, “buisine”).

3985 souffle. A bladder pipe is “a wind instrument in which a reed is enclosed by an animal bladder.” In the early Middle Ages, they were played in a “courtly context,” but “by the later 15th century [it] had become predominantly a folk instrument” (Grove Music Online, “bladder pipe”).

3987 penne. A plectrum is “a general term for a piece of material with which the strings of an instrument are plucked”; in this case, it is a “penna” or a quill (Grove Music Online, “plectrum”).

3989 Quant fait eurent une estampie. Originally a sung form of music, the estampie had become strictly instrumental by Machaut’s time (Oxford Companion to Music, “estampie”).

3997 parsons. There is no other surviving mention of a game called “parsons.”

4066–82 Et je vueil . . . . parfaire ceste alience. The exchange of rings here and the appearance of Hope as a kind of officiant to “fulfill our union” likens this ceremony to a wedding rite.

4257 Car qui bien aimme, a tart oublie. This line repeats the identifying first line of the Lay de plour, which immediately follows JRN. But this expression is also proverbial and might not be a literary self-allusion here.

4258–72 Mais en la . . . . plus ou mains. These lines contain an anagram/acrostic of Machaut’s name. See also JRB explanatory note to lines 2055–66 and Confort note to lines 27–44 below.

4276–97 Bonne Amour, je . . . . sera mes dis. The poet’s “devotion hinges on a wish addressed to Love: unlike the typical lover who might desire a future meeting with his lady, our narrator requests only that Love assure a reading of his work by his lady” (McGrady, “Guillaume de Machaut,” p. 111). Again, this emphasis on writing and reading is a running theme throughout the Remede.

MACHAUT, THE BOETHIAN POEMS: TEXTUAL NOTES

Abbreviations: A: Paris, BnF, fr. 1584 [base text]; B: Paris, BnF, fr. 1585; C: Paris, BnF, fr. 1586; D: Paris, BnF, fr. 1587; E: Paris, BnF, fr. 9221; F: Paris, BnF, fr. 22545; FP: Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Panciatiachiano 26; G: Paris, BnF, fr. 22546; H: Oeuvres de Guillaume de Machaut, ed. Hœpffner; I: Paris, BnF, n.a.f. 6221; J: Paris, Arsenal 5203; Jp: Le Jardin de Plaisance et Fleur de Rethoricque (Paris: Ant. Gérard, [1501]); K: Berne, Burger-bibliothek 218; Ka: Kassel, Universitätsbibliothek, 4° Ms. Med. 1; M: Paris, BnF, fr. 843; Mn: Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, 10264; P: Paris, BnF, fr. 2166; Pa: Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Fr. 15; Pe: Cambridge, Magdalene College, Pepysian Library, 1594; Pit: Paris, BnF, it. 568; Pm: New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 396; PR: Paris, BnF, n.a.f. 6771; R: Paris, BnF, fr. 2230; Trém: Trémoïlle, Paris, BnF, n.a.f. 23190 [lost]; Vg: Ferrell-Vogue, private ownership of James E. and Elizabeth J. Ferrell; W: Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales, 5010 C.

For reasons set out at some length in the General Introduction, this edition takes MS A as an authoritative text for Machaut’s works, including the two dits included in this volume. Because of the unique authority of A, and for the sake of consistency across a complete edition that must depend on the later omnibus MSS for the principal works of the author/composer’s later career, the practice has been to deviate from A’s readings only in clear cases of spelling error, scribal misinterpretation, and omissions, and miswritings of other kinds. Given medieval orthographical practices, which are far from consistent in the modern sense, we are aware that the category “spelling error” is occasionally a matter of interpretation.

LE REMEDE DE FORTUNE

A and C are the best witnesses to the text of the Remede, which offers little in the way of difficult or problematic passages. The notes here offer no variants from the other MSS; these variants can be found in Oeuvres de Guillaume de Machaut, Vol. 2, ed. Hoepffner and Roy de Behaingne and Remede de Fortune, eds. Wimsatt and Kibler.

131 retollir. So A. C reads retenir and H emends accordingly, but both readings mean about the same, hence there is no compelling reason to reject A here. The translation offered covers both possibilities.

151 peinne. A: peinme, a misspelling.

247 Et qui s’umilie essauciés. So C. A: Et qui s’essause humiliez. A confuses the familiar Scriptural quotation, so read with C.

248 noms. A: mons, a misspelling.

330 maintieng. A: maitieng. Missing nasal stroke.

507–10 Car en moy / Joye en croy / Pour de mon cuer vray / Remaint en soy. So C. A: car de moy / a lottroy / et de mon cuer vray / qui maint en soy, which is grammatically deficient and does not give good sense.

537 autrui. A: autrai, a spelling error.

611 M’est. A: met, a misspelling.

695 Eins. A: Enis, a misspelling.

733 despondre. So C. A: respondre is from line below.

740 qu’il le. So C. A reads qui le, an eyeskip error.

768 congnet. A: coingnet, a misspelling.

791 murs. A: imurs, a misspelling.

846 vausist. A: venrst, a misspelling.

873 clerement. A: clement, a spelling error.

892 fermeté. A: femeté, a misspelling.

996 aimme. A: aimne, a misspelling.

1049 Stanza break. So C. A has no stanza break here, though one seems indicated.

Les. So C. A: Es, a spelling error.

1053 aveugle. A: aungle, a misspelling.

1097 Je. A: Le, a misspelling.

1166 annemie. A: amiemie, a misspelling.

1169–70 Sa force est qu’en cheant est forte / En desconfort se reconforte. So A. In C and E, A's line 1170 is replaced by so foy est qua nul foy de porte, and this new line is placed before A's line 1169.

1185 est drois. So A, which may be an error or a revision. C: est voirs.

1199 remis. A: renus, a misspelling.

1213 estraingnis. So A, which may be an error or a revision. C: estranges.

1273 Einsi. A: Enisi, a misspelling.

1311 Lettre. A: lestre, which may be a clear spelling error or an attempt to turn a near rhyme intro a true rhyme.

1406 chace. So H. A: trace.

1477 s’einsi. A: senisi, a misspelling.

1549 odeur. A: oedeur, a misspelling.

1622 sanblance. A: sanlance, a misspelling.

1658 plus en a. So H. A: plus a, which is grammatically awkward.

1664 Quar. So H. A: Queir.

1737 langage. A: lagage, a misspelling.

1746 mauvais. A: mauais, a misspelling.

1776 homme. A: home, a misspelling.

1793 comment. A: commant, a misspelling.

1817 bien. A: bieni, a misspelling.

1843 le congnoistra. So C. A: la congnoistra, but the antecedent of the pronoun is the pretend lover, so the gender of the pronoun in A is incorrect.

1848 desloial. A: deloial, a misspelling.

1854 Par. So C. A: Pour.

1869 enmi. A: enmij, a misspelling.

1876 pleinnes. A: pleines, a misspelling.

1902 Comme. A: come, a misspelling.

1917 certeinnement. A: certeinnemet, a misspelling.

1977–78 douce . . . . clere. C: has clere for douce in line 1977 and douce for clere in line 1978.

2053 Je te pri. So A. C: or te pri.

2054 Que. A: Qu, a misspelling.

soles. A: soies, a misspelling.

2089 doit. A: droit, a misspelling.

2105 Ou sa. A: O sa, a misspelling.

2205 Pour la grant chaleur. So C. A: de la grant chaleur, which is awkward.

2216 greinne. A: greine, a misspelling.

2255 crostee. A: crotee, a misspelling.

2263 s’elle. A: celle, a misspelling.

2361 Et. So H. A: De.

2362 couleurs. So C. A: couleur, a spelling error.

2365 anelet. A: anenelet, a misspelling.

2383 plus griefment. So C. A: repeats plus asseure from previous line.

2392 commant. A: commat, a misspelling.

2399 heüst. A: hest, a spelling error.

a moy. A: amo, a misspelling.

2451 porroies. So C. A: perdroies, an eyeskip from the next line, which ends with that word.

Before 2483 Here and elsewhere throughout this section of the poem A reads incorrect rubrics that mis-assign the speeches of Esperence and Amant. I read the rubrics here throughout with C.

2505 comment. A: coment, a misspelling.

plaingnes. A: plangnes, a misspelling.

2523 tesmoing. A: tesmong, a misspelling.

2524 tesmoing. A: tesmong, a misspelling.

2547 peinne. A: peimne, a misspelling.

2580 conduira. A: conduire, a spelling error.

2603 en sent. So C. A: omits.

2633 tiennes. A: tennes, a misspelling.

2665 pleinne. A: pleninne, a misspelling.

2794 Trebles. A: tresbles, a misspelling.

2797 Je. A: Le, a misspelling.

2900 me faisoit. C: men faisoit, which also gives good sense.

2950 j’ensieuisse. A: iesiusse, a misspelling.

3003 m’en. A: me, a misspelling.

3005 remembrance. A: ramembrance, a misspelling.

3009 qu’estoie. A: qustoie, a spelling error.

3019 Me fait cent fois. So C. A: font, which is grammatically awkward.

3027 ottroie. C: envoie, which also gives good sense.

3172 me departiray. C: men departiray, which also gives good sense.

3194 Qui. A: Qi, a misspelling.

3198 Qu’avant. A: Quavent, a misspelling.

3209 adurci. A: adouci, an eyeskip error.

3214 si. A: ci, which is a clear spelling error.

3225 Aprés les me fais esperer. So C. A: omitted.

3251 premereins. C: souvereins, which also gives good sense.

3279 D’onneur. A: Donner, a misspelling.

3314 Deingne. A: Deingnott, a misspelling.

3353 Bon Espoir. C: dous espoir.

3381 dame. A: dime, a misspelling.

3382 në ame. So C. A: ne jame, which gives inferior sense.

3449 chanson baladee. A: Chanson Balladee, here altered for literary reasons to make the spelling of this lyrical genre consistent with other forms of balade in the text.

3488 l’ardour. So C. A: omits, a scribal error.

3601 estreint. So A. C: destraint, which also gives good sense.

3631 S’estoit. So A. C: estoit, which also gives good sense.

3722 Comment. A: coment, a misspelling.

3723–24 Qu’onques mais . . . . je grant merveille. So C. A omits.

3837 Loiaus. A: Laiaus, a spelling error.

3843 Esperence. A: esperen. Missing letters.

3869 dessevrer. A: deserver. Missing letters.

3882 leurs aventures. So A. C: ses aventures also gives good sense.

3884 je pensoie. So A. C: je sentoie, which also gives good sense and fits the rhyme scheme.

3891 fumes. A: funes, a spelling error.

3895 plus. A: plous, a spelling error.

3936 crotes. A: cretes, a spelling error.

3973 de saus. C: de scens also gives good sense.

4062 Quant. A: Qunt. Missing a letter.

4135 duisoit. A: duison, a miswriting.

4163 Comme. A: come, a spelling error.

4175 Comment. A: Coment. Missing nasal stroke.

4268 couvient. A:couviert, a misspelling.

4271 ne. A: ni, a misspelling.

MACHAUT, THE BOETHIAN POEMS, VOLUME 2: NOTES TO THE MUSIC BY URI SMILANSKY

Abbreviations: see Textual Notes.

As detailed in the front matter, the following comments do not contain variants lists, but discuss the problems presented by the readings in MS A and the way they were solved in the editions supplied. Additionally, a concordance list, technical and structural data, and general remarks head each discussion. In the “text structure” sections, letters indicate single rhyme endings. Numbers indicate the syllable count of the line in question. Apostrophes indicate an unstressed appendage syllable not included in the syllable count. Further explanations of terminology and signification technique can be found in the “Music Glossary,” pp. 571–73.

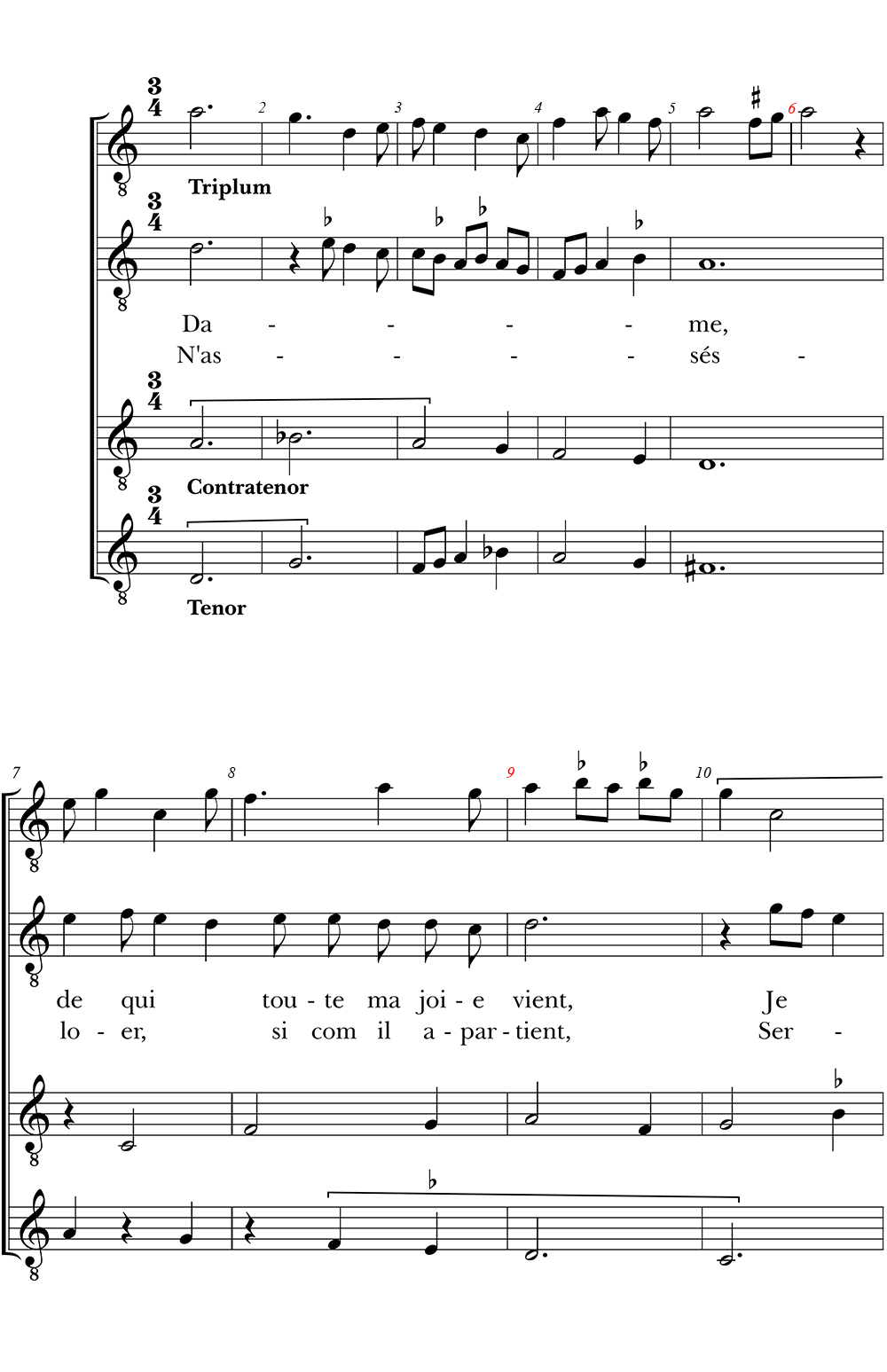

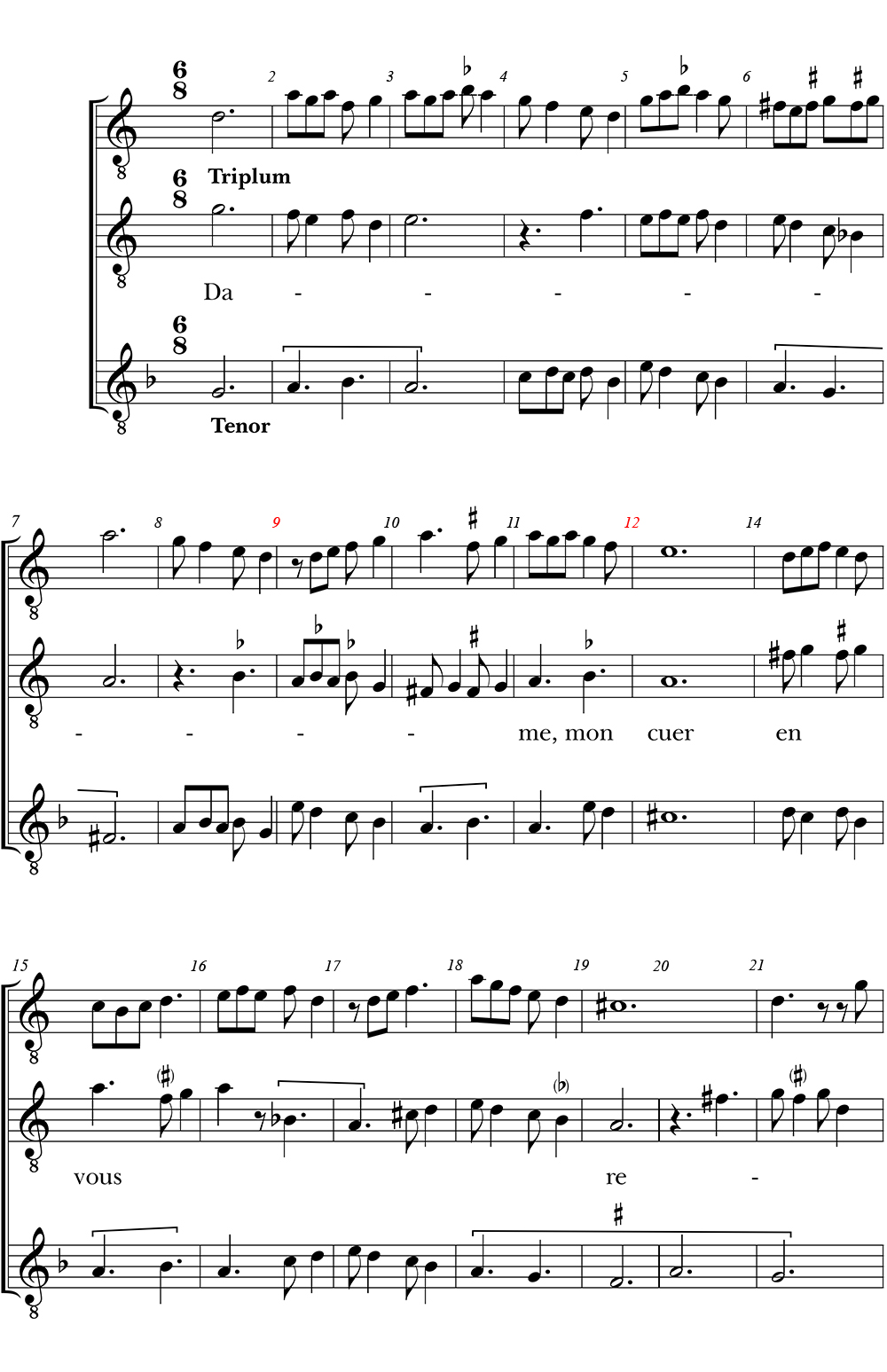

THE LAY: QUI N'AROIT AUTRE DEPORT (lines 431–680)

Comments on the readings in MS A

signature The placing of the first fa-sign may suggest a signature accidental, but as only one B follows, I saw it as a specific instruction and did not reproduce it in the following lines.

m. 38 The second note of the measure is a brevis instead of a longa. As this does not work, the rhythm is corrected according to the repetition in m. 56.

m. 45 The placement of ‘tels’ in the first underlay and ‘par’ in the second is not clear. Each could also be moved one note earlier (but see also m. 63, where the underlay is clearer).

m. 54 The first note was originally a brevis rather than a longa, but as this does not work, the rhythm is corrected according to the first appearance in m. 36.

m. 55 The fa-sign does not necessarily have to signify a signature change, but as the next line has one in the signature, it is interpreted as such.

m. 81 The whole measure, which ends the line, was copied a third too low and subsequently corrected through the insertion of a new clef. Here the MS reading is erroneous and corrected in the edition. The next line continues with the normal clef as usual.

m. 96 The first note of the measure, which is the last note of the line in the manuscript, was written a third too low; compare the first iteration in m. 81. Here, though, no correction took place. The rest of the measure (appearing on the next line) duplicates the corrected earlier reading.

m. 103 The longa here is not followed by a dot or a rest (as in the repetition at m. 114), so in theory it should be imperfected by the next note. As this reading avoids a cadence at the end of the formal section, it is adjusted to chime in with the repetition (but without inserting a rest).

m. 120 The rhythm here is different from that of the repetition (m. 133–34). The change is due to the single inclusion or omission of a stem attached to the second note E (present here and missing in the repetition). While this may be a simple mistake (the stemmed version is supported by all other sources) both alternatives are kept here, as each is as technically and musically satisfactory as the other, and the difference can be supported by links to the text.

m. 224 Either the rest line was copied too long, or it was replaced by a separation line. As this is the ouvert cadence of this strophe, the intention is clear regardless.

m. 229–31 These measures were initially copied with a mistake at their beginning, but then erased and copied again correctly.

m. 255–60 The underlay is not clear here. The arrangement chosen mirrors that of m. 241–46. The last line of text in this strophe could also be made to start with the second ligature of m. 256.

m. 261–62 To enable a rhythmically satisfactory reading, a brevis rest is omitted between the second and third notes of m. 262 (following the reading of the repetition at m. 278). While being the most straightforward solution for the readings in this source, it is contradicted by virtually all concordances, which include a rest for both versions. Consequently, the full critical version of this work (to be found in Volume 10 of this edition) presents a different solution, by which the first brevis of each half strophe is taken as an upbeat.

m. 263 The positioning of the second syllable is not clear here or in the repetition at m. 279. The version here privileges ligature-spacing over vertical alignment of text and music.

THE COMPLAINTE: TELS RIT AU MAIN (lines 905–1480)

Comments on the readings in MS A

signature It is possible to transcribe the complete Complainte in a one-flat signature throughout as virtually all Bs are appended by ficta (or appear later on in a line after a fa-sign). Still, as the distribution of signs was not consistent, single inflections rather than a signature are used.

m. 5 The rest was originally of a perfect longa (stretching over three spaces in the manuscript and lasting a whole measure in the transcription), but an erasure in the source corrected it to the right length.

m. 8 The F brevis was originally copied twice (once at the end of a line and again at the beginning of the next), but the second appearance was subsequently erased.

m. 12 The notation is a bit strange here. It might be that the original reading was [musical notation coming soon] and only later changed to plicated [musical notation coming soon].

m. 14 This measure reads [musical notation coming soon], followed by an erasure. Keeping the longa perfect though, would result in the ouvert and clos endings being syncopated (the final longae of this form part are also specified as perfect). The dot is therefore ignored, maintaining the rhythmic integrity of all line endings in this work, and following the readings given for the ending of the second form part.

m. 22 This measure signals the end of folio 55v. In the underlay of the second text, ‘gist’ appears only at the beginning of folio 56r. The manuscript reading, therefore, has only one syllable ‘qui’ in the second text of m. 22 and fits in three syllables (‘gist,’ ‘mas’, and ‘en’) in m. 23. As the first text organization is clear and all other appearances of this kind of fast rhythmic progression are contained within a single melisma, this reading was not adopted.

m. 33 The two ligatures in this measure, which appear at the end of a line, were copied a third too high in the manuscript, creating surprising melodic progressions which are ‘corrected’ here.

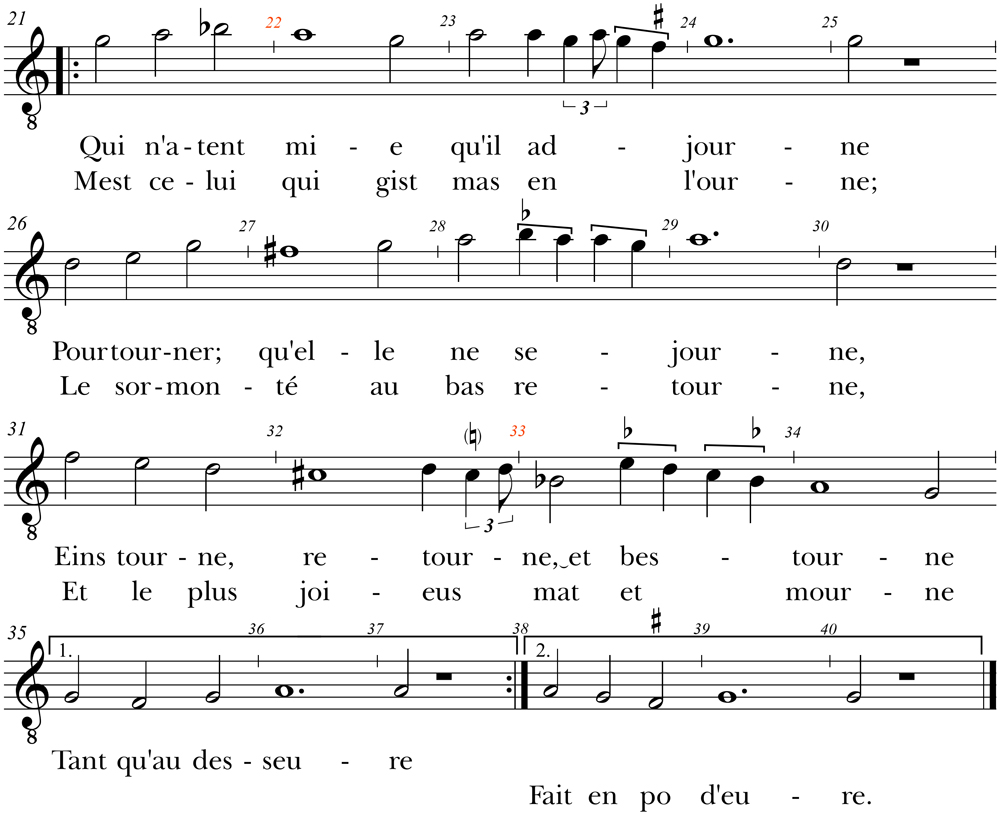

THE CHANSON ROIAL: JOIE, PLAISENCE, ET DOUCE NORRITURE (lines 1985–2032)

Comments on readings in MS A

title The original has ‘Chason roial’ as its title. The omission of the ‘n’ is taken as a simple mistake.

m. 5 The augmentation here, while making musical sense and respecting the ligature structure, goes against the notational rules. The manuscript has two breves followed by the ligature, so, technically, the second note of m. 5 should be halved and the last note of m. 6 doubled. The correction made respects the ligature structure and makes more rhythmic sense in the context of this song, both in terms of repeating musical rhythms and in terms of text delivery and arrangement.

m. 6 The syllable ‘-tu-’ of the second underlay is missing. The omission occurs over the line break in the manuscript.

m. 29–30 No dot appears after the longa in m. 29, which, strictly speaking, should call for its imperfection by the next brevis and the perfection of the remaining longa (G) in m. 30 to fill its entire length. This reading is not adopted, as the first longa in question ends a line in the manuscript, creating a visual separation between it and the following brevis. Musically, the regularity of the preceding sentence structure, the ending of the A-section, and the otherwise non-existence of brevis (half-note) upbeats in this song also support this reading. It is even possible to imagine a missing rest here, following the punctuation technique of the other text-lines.

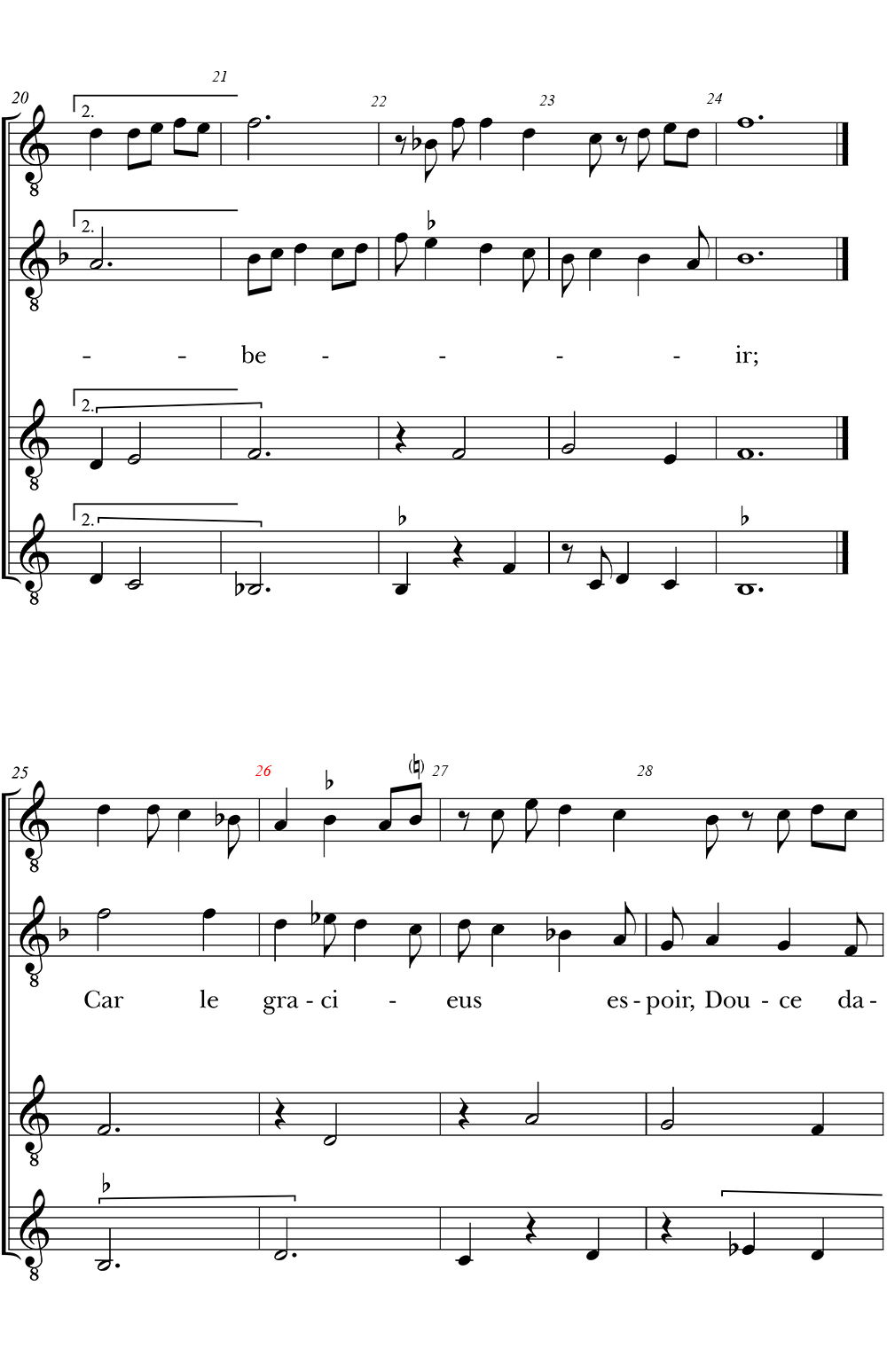

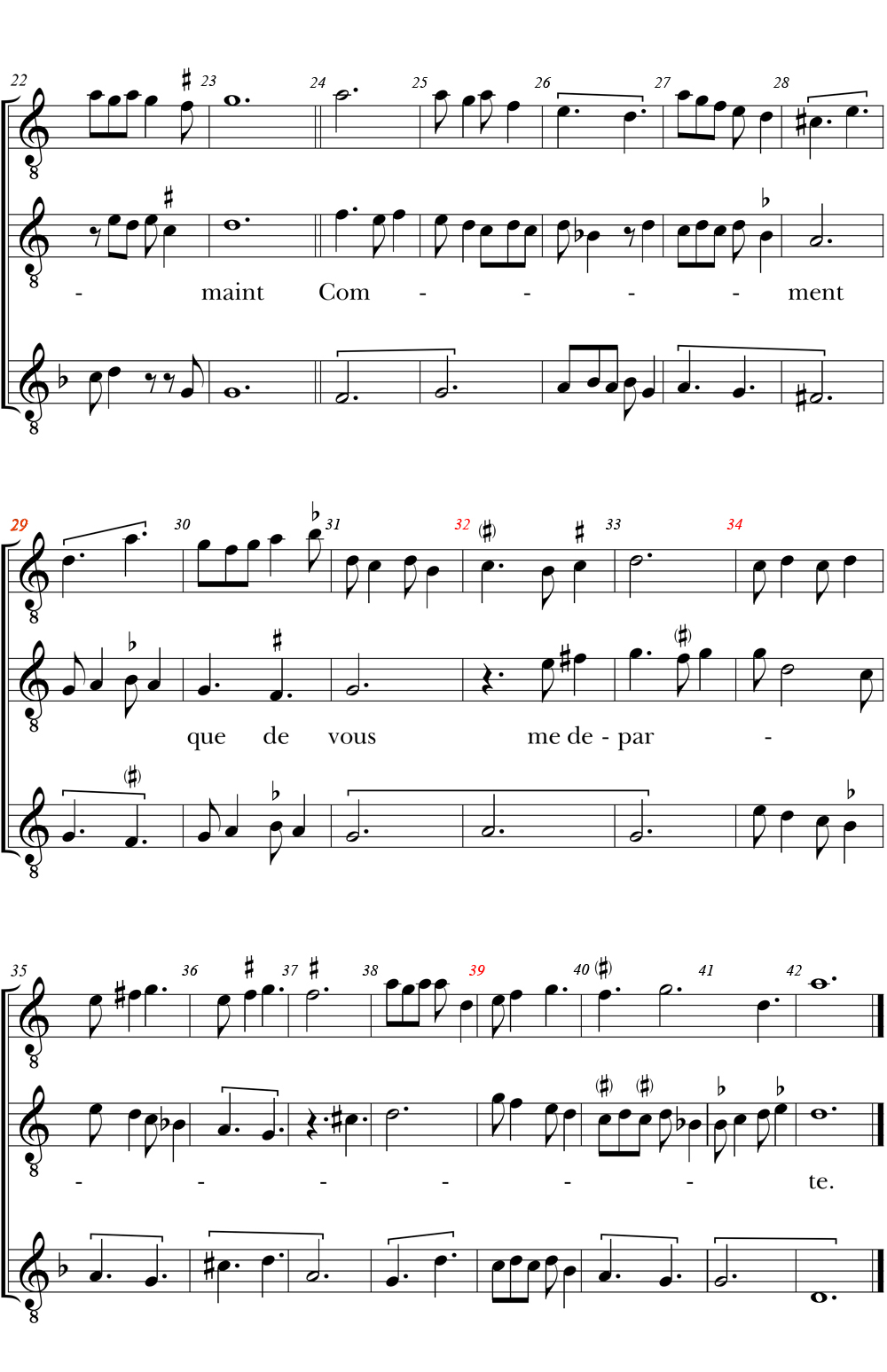

THE BALADELLE: EN AMER A DOUCE VIE (lines 2857–2892)

Comments on the readings of MS A

repeats All the ouvert and clos endings have longae for their final notes in the manuscript, but all are transcribed as a single rather than a double measure (m. 12, 14, 30 and 32).

m. 3 triplum The second rest is not in the manuscript. Technically, one can read this measure as it stands, taking the rest out and augmenting the second C. The literal reading is not adopted in order to maintain the recurring rhythmic motive, prevalent throughout this voice (see also m. 8).

m. 4 contratenor The mi-sign (natural) may just as well refer to the C.

m. 7 cantus The second note could imperfect the first (move one position backwards), but spacing, positioning of the fa-sign, and the following rhythmic formula suggests the solution presented.

m. 11–12 triplum An erasure and correction occurred in the ouvert cadence.

m. 16 tenor The line break in the manuscript occurs between the second and third beat of the bar. Before the end of the line some erasures took place.

m. 20–21 contratenor There is no dot after the F8. A literal reading, therefore, would move the first note of m. 21 back to the end of the previous measure. While this is possible, the minor correction is adopted in order to facilitate a fuller cadence on m. 21.

m. 21–22 triplum These two measures do not work as they stand in MS A. The rhythm given: [musical notation coming soon] is two semibreves short, making it impossible to solve the problem using augmentation. For once, since so much is missing from MS A, the version presented is taken from another source, MS C.

m. 22, 29 tenor The E7 here were given as a key signature which does not include B7. As this is senseless in common practice, it seems more appropriate to move the inflections into the staff and attach them to the specific notes they affect.

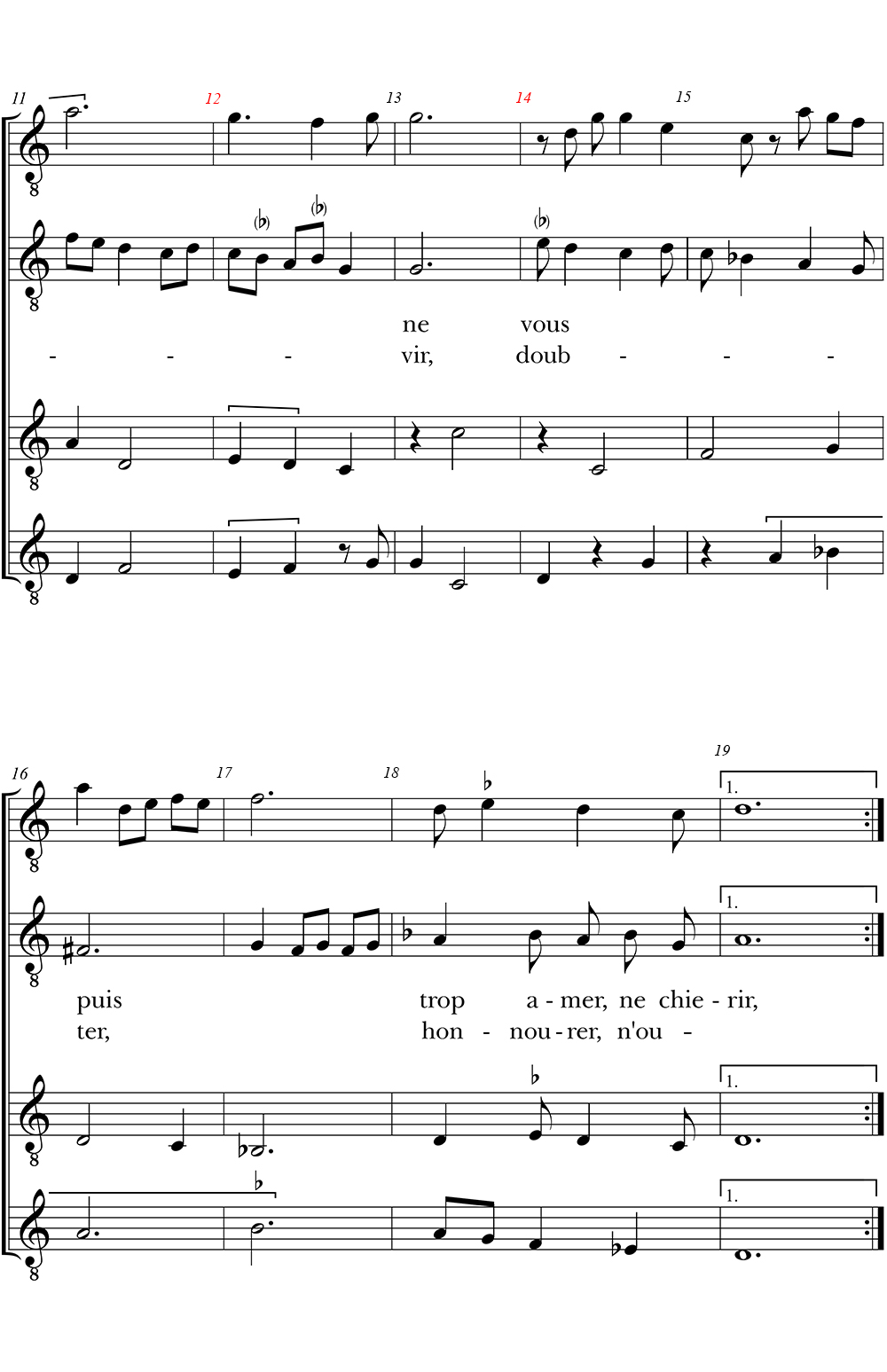

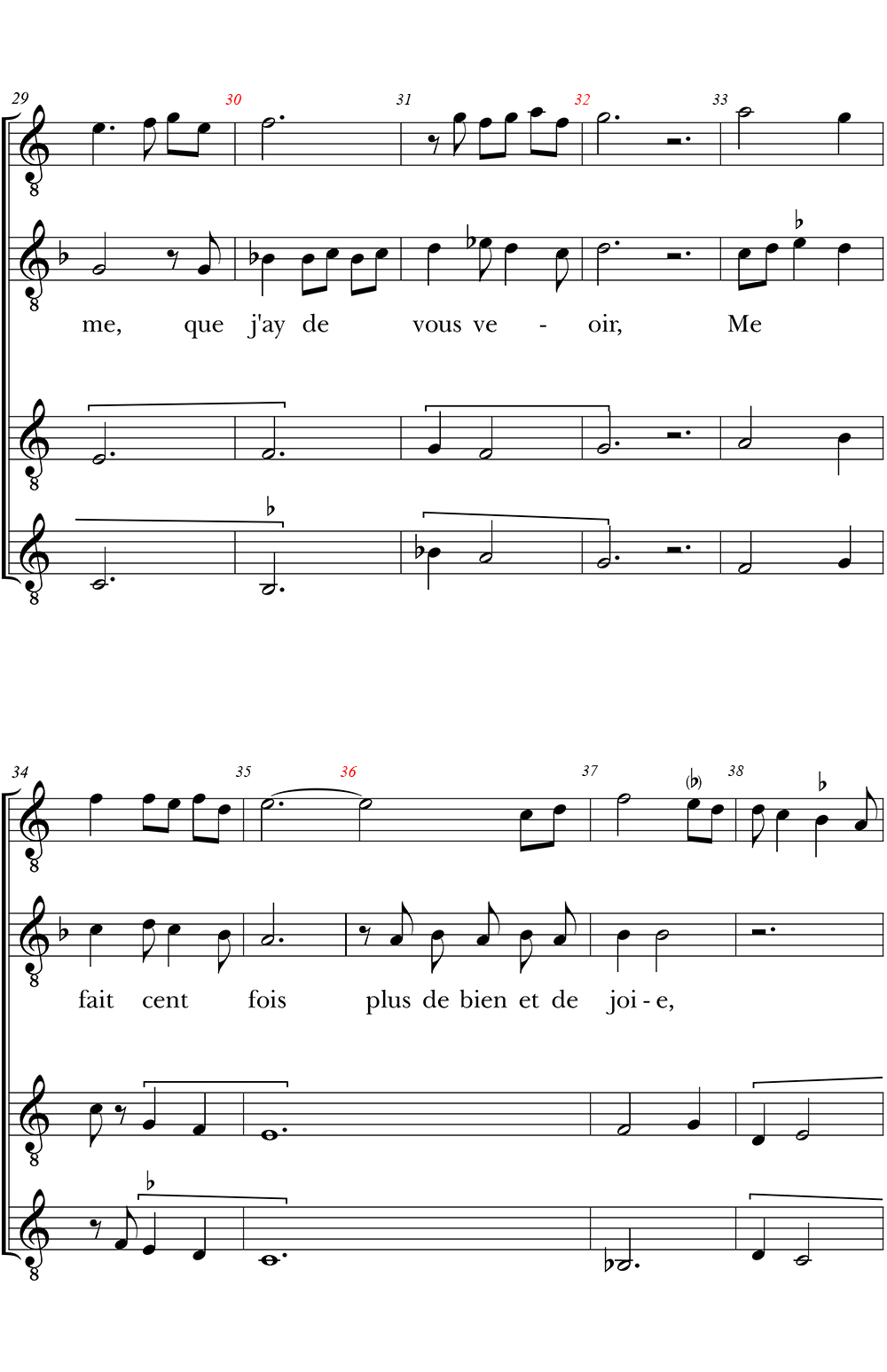

THE BALADE: DAME, DE QUI TOUTE MA JOIE VIENT (lines 3013–3036)

Comments on the readings in MS A

m. 1–9 triplum The first line of the triplum was originally omitted and added later above the intended first line on a rather wavy staff. Interestingly, this new beginning received its own decorated initial (but not a new incipit).

m. 4–6 triplum A stem is missing from the first A ([musical notation coming soon] rather than [musical notation coming soon]). m. 4 was copied a second time with all the required stems, but notated a third too high. The erroneous transposition was maintained for the following two measures. This whole section appears in the middle of the added line, and cannot, therefore, be blamed on a line break in the source.

m. 9 triplum The last four notes of this measure (which correspond to the last four notes of the added line) were written a tone down in the musical concordances for this piece. While this may be a mistake, the variant is entirely acceptable and is maintained here.

m. 12 triplum An erasure occurred, but it is impossible to say what the second half of the measure originally contained.

m. 14 cantus An erasure occurred at the end of the measure, seemingly removing a B7 semibrevis which stood in the place of its last note.

m. 25–26 contratenor That no dot appears between the measures may suggest imperfecting the first rather than the second brevis. Due to the positioning of the rest and the rhythmic pattern of the voice as a whole, I decided not to adopt this reading.

m. 26–30 cantus In the manuscript, this line has no fa-signs in its signature, but as the two previous and five subsequent lines do have it, and it is clear that all the Bs in it are to be flattened (see specific indications kept in the score in m. 27 and 30), the signature is maintained throughout.

m. 32 all On the interpretation of the simultaneous rests in all voices, see the “Music Presentation” section, pp. 79–80. It should be noted that such signs are more commonly found before the beginning of refrains or at the end of other form parts.

m. 36 triplum The two minimae are notated a tone up in the other concordances of this work. While the alternative reading perhaps works better and the correction could be made on purely melodic grounds without recourse to the other sources, the unusual original reading still works, and is, therefore, kept.

m. 44–45 contratenor The last line of this voice is the only one to have a flat in its key signature, but a mi-sign appears before the only B it contains.

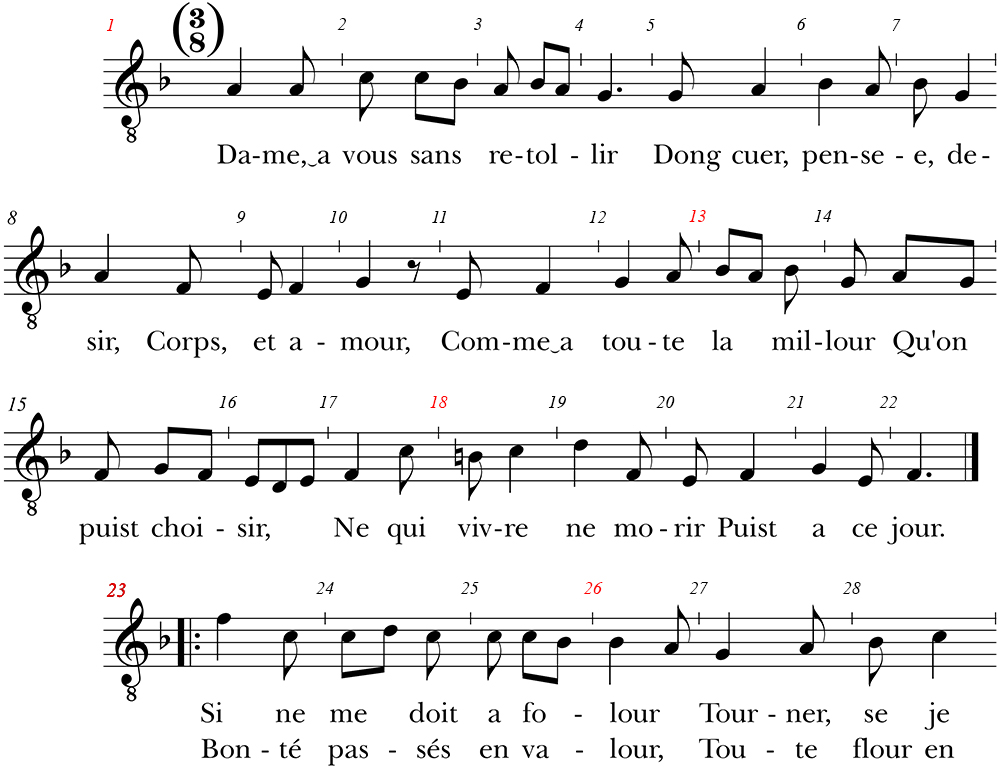

THE CHANSON BALADEE (VIRELAI): DAME, A VOUS SANS RETOLLIR (lines 3451–3496)

Comments on the readings in MS A

signature A one-flat signature was kept throughout, even though the signature does not appear in 4 of the 12 lines of music (m. 11–27). Of these four, the first and last places the appropriate fa-sign within the staff, the second specifies a mi-sign before the only B in it, and the third does not contain this pitch. The regularity of application led me to maintain the signature accidentals.

m. 13 The positioning of ‘mil-’ is hard to determine. It could also be placed a note earlier (but see the underlay in m. 24–25 and 45–46).

m. 18 The mi-sign was placed before the C in the source and may refer to it. The decision to refer it to the B instead is taken on melodic and modal grounds — both the F–C8 leap, and the strong directional pull to D in a work with such a strong modal center on F were deemed too surprising.

m. 23 In the manuscript, the B-section begins at the top of a new column, even though the penultimate line in the previous one contains only the last two notes of the A-section and the last line of the column is completely empty.

m. 25–26 Other sources present these measures a tone lower, but as this version works just as well, the variant is maintained.

m. 38 ‘-tre’ appears at the end of the previous line in the manuscript, but with the elision the intention here becomes clear.

m. 42–43 No dot appears after the rest, so according to the strict rules one should have a dotted G and push the remainder to the next measure followed by two eighth-notes E–F. The spacing and position of the rest, though, suggests that the intention here was to reproduce the rhythm given in the first version of the A-section (m. 10–11).

m. 50 This measure begins a line which has a fa-sign as part of its signature. Thus, the B9 specified in the parallel musical location in the refrain (and placed in brackets above the staff here) should perhaps not be reproduced.

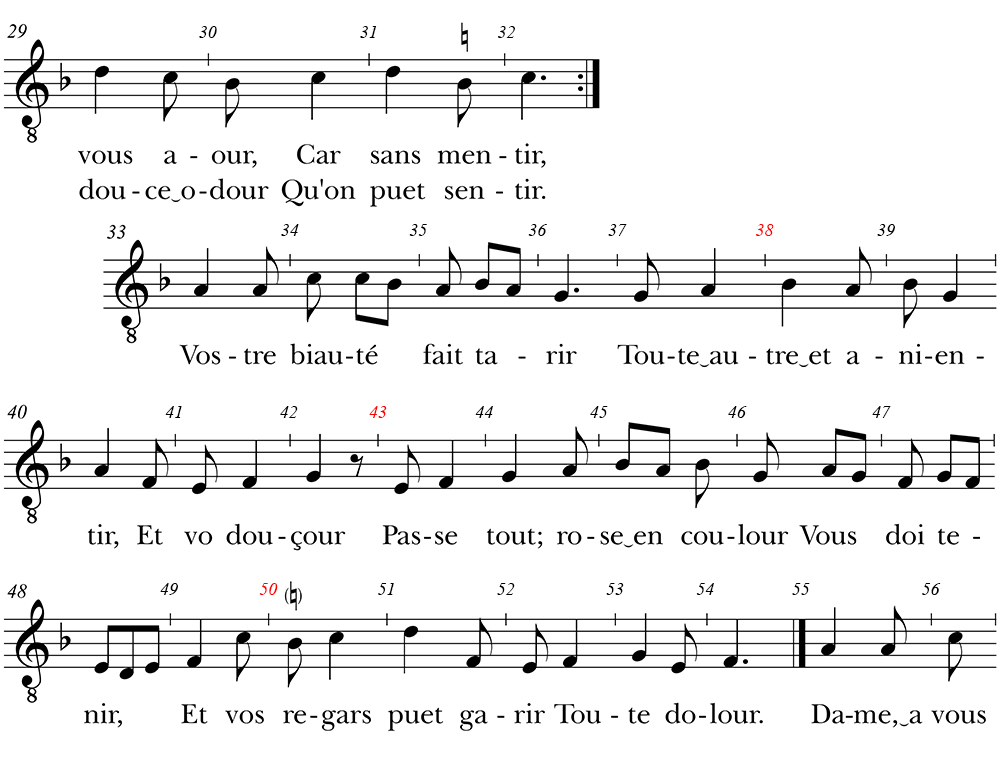

THE RONDELET: DAME, MON CUER EN VOUS REMAINT (lines 4108–4115)

Comments on readings in MS A

m. 9 tenor Originally [musical notation coming soon] rather than [musical notation coming soon]. As it stands, the last note of the measure should be tied over, forcing a syncopation lasting until the first A in m. 11 (which would then be shortened). This kind of progression does occur in Machaut’s works, but usually not in the tenor, and it seems unlikely that this was the intention here.

m. 12–13 cantus An erasure (or other damage) occurred here, but it is hard to determine its reason.

m. 24–29 cantus Some serious erasures took place here, most clearly between the middle of m. 25 and the middle of m. 27.

m. 27–39 tenor The signature fa-sign is missing for this line (which ends in the middle of m. 39, before the D), but it seems both Bs it contains should be flattened nonetheless, suggesting this was a simple omission. Wanting to mirror this in the edition without suggesting too strong a change, I silently omit the key signature from the line containing m. 29–34.

m. 32 cantus The rest is missing, but can easily be added from the polyphonic context.

m. 34 cantus The first note is seemingly written over an erasure, but may be part of the larger correction in m. 24–29 mentioned above.

(t-note) (see note) |

(t-note) (t-note) |

(t-note) (t-note) (t-note) (see note) (t-note) (see note) (see note) (see note)(t-note) |

(t-note) (t-note) (t-note) (t-note) (t-note) |

(see note) (t-note) |

(see note) (see note) (see note) (t-note) (see note) (see note) (see note) (see note) |

(t-note) |

Go To Le Confort d'Ami

The miniatures (images) from MS A are not included in this digital edition, but are available in the print version. To view these images, see also the Bibliothèque nationale de France's digital edition on Gallica: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84490444.