1. More than Maid

Marian, often given the containing sobriquet "Maid," is both an intermittent and elusive figure in the Robin Hood myth. She does not appear in the late medieval yeoman ballads or, with one exception, their seventeenth and eighteenth century broadside ballad descendants. She is an initial presence in sixteenth and seventeenth century gentrification, is less certain of a place on the eighteenth century stage, but becomes from the nineteenth century on a fixture as Robin Hood's partner, often wife, occasionally mother of his child or even children. She plays a usually substantial role in film, and has recently come to the fore in broadly feminist reworkings of the myth. Even when she is recurrently present, substantial variation has occurred in her activities and meaning, and it may be her complexity takes her back before the early outlaw ballads to the medieval French pastourelle tradition.

Although she is essentially Robin's only female partner, she is functionally quite unlike him, as the meaning given, whether social or personal, to her identity and actions does not have his consistent core of meaning. He is always in some way anti-authority; her role and meaning have no such constant vanishing-point. A naïve reaction might be that she changes in response to his positional variety, whether, for example, he represents a noble lord or a Victorian national hero, but that hardly explains how Marian can become for the Romantics an image of ennobling desirability or in a modern feminist context the opposite, a model of competence and even dominance. Marian is, it appears, primarily invoked by the gender-related concerns of the social environment in which she appears: she does not resist authority so much as represent a changing alternative...

Read More

Read Less

1. More than Maid

Marian, often given the containing sobriquet "Maid," is both an intermittent and elusive figure in the Robin Hood myth. She does not appear in the late medieval yeoman ballads or, with one exception, their seventeenth and eighteenth century broadside ballad descendants. She is an initial presence in sixteenth and seventeenth century gentrification, is less certain of a place on the eighteenth century stage, but becomes from the nineteenth century on a fixture as Robin Hood's partner, often wife, occasionally mother of his child or even children. She plays a usually substantial role in film, and has recently come to the fore in broadly feminist reworkings of the myth. Even when she is recurrently present, substantial variation has occurred in her activities and meaning, and it may be her complexity takes her back before the early outlaw ballads to the medieval French pastourelle tradition.

Although she is essentially Robin's only female partner, she is functionally quite unlike him, as the meaning given, whether social or personal, to her identity and actions does not have his consistent core of meaning. He is always in some way anti-authority; her role and meaning have no such constant vanishing-point. A naïve reaction might be that she changes in response to his positional variety, whether, for example, he represents a noble lord or a Victorian national hero, but that hardly explains how Marian can become for the Romantics an image of ennobling desirability or in a modern feminist context the opposite, a model of competence and even dominance. Marian is, it appears, primarily invoked by the gender-related concerns of the social environment in which she appears: she does not resist authority so much as represent a changing alternative to it. A notable feature is that a strong and active Marian appears to invoke from its own force rather than by source-imitation a "false Marian," who pretends to be Marian in order to humiliate both her and others who value or depend on her.

Gender-related forces both benign and malignant swirl around this potent but often enigmatic figure.

2. Pastourelle Marian and Bergerie Robin

Early French lyric poetry has Marian (often spelt Marion, even Marot or Mariet) in pastourelle as a pastoure, shepherdess, pursued by some intruder, usually lordly. When she has a recognized partner he is called Robin: he is not surnamed Hood, though he may be Robin des Bois, "of the woods." These songs, found across France, were gathered and elaborated in a full-length semi-opera by Adam de la Halle, using traditional themes and tunes, named Robin et Marion (c.1283).

This Robin is not an outlaw—though he often resists Marian's admirers—but a working peasant, and he and his friends are given to simple celebrations depicted in the bergerie songs in which Marian rarely appears. The bergerie events sound much like the Robin Hood play-games, which have only rare signs of female presence. The Kingston play-game records of 1509-10 (found in the Records of Early English Drama series) are the first to record Marian's presence; and there are few references to her after that. It would seem that as the play-game appears close to the bergerie, not the pastourelle, there is no sub-generic requirement here for Marian's presence—nor is there any outlaw activity in them. When Marian's name appears in early records of popular drama it usually links to a Morris dancer, partnered by a Friar (who is also present in the Kingston records), like the unnamed wench who finally dances with the friar in the short "Robin Hood and the Friar" play of about 1560. Though some commentators have called her Marian, only in rare and late Morris dances is there a Marian in this mode. Both the play-games and the early popular drama lack any clear sign of the previous and later heroine Marian, and in this they are like the late medieval yeoman ballads. As the English outlaw tradition is evidenced in references and early ballads, Robin is hostile to social and religious authority, and there is no role for Marian. This seems simply realistic. Men tended to live as outlaws in summer, and in small groups, often with relatives and friends, and they did not take their womenfolk to the wilds with them. It might seem no accident that Robin's only loyalty across gender in the early ballads is to the Virgin Mary. At the end of the Gest he does claim to the king he has created a forest chapel to St Mary Magdalene, who might be seen as the good outlaw of the New Testament. It is possible to read both of these religious Maries as a stand-in for Marian, bringing limited aspects of the female into the forest story, but they do not of course survive the reformation.

Even when in the seventeenth-century broadsides the tradition develops rapidly, women play very limited roles: the Queen in "Robin Hood and Queen Katherine," a mother whose sons are saved in "Robin Hood Rescues Three Young Men," and a wry crone who saves Robin by exchanging clothes with him in "Robin Hood and the Bishop."

3. Lady Marian, 16th Century Onwards

Marian's return to Robin and her arrival at the center of the English outlaw tradition is part of gentrification. When he is made a lord, with a land, he must have a lady. In Anthony Munday's The Downfall and The Death of Robert Earle of Huntington of 1598-99, she is before her forest exile as Marian known as Lady Matilda Fitzwater, derived from Michael Drayton's 1594 poem Matilda the Fair and Chaste Daughter of Baron Fitzwater.

Munday’s Marian does not influence succeeding stories much: in this version she survives Robin’s death very early in the second play and is pursued by Prince John to her own tragic fate. Marian as martyr did not catch on (though there will be examples in nineteenth-century fiction, deriving from the summary of the plays in Ritson’s Introduction to his 1795 ballad-collection), but Munday introduced a very striking motif which has seemed almost compulsive for authors who give Marian a substantial role, the "false Marian," a witch-like betrayer of Robin.

In Munday’s Downfall Queen Eleanor, mother to King Richard and Prince John, lusts after Robin as much as John does after Marian, and early on, as Robin and Marian flee, she persuades her to change clothes—ostensibly for Marian's safety, but in fact because the queen desires him. This "false Marian" feature will recur, and it seems that the more sexually aware and active is the love of Robin and Marian, the more likely there is to be a malign double for her. The motif appears to relate to the masculinist anxiety that woman can be delusive and dangerous as well as—or instead of—being passive and supportive. This keeps going through the tradition, right on to the 1991 film with Uma Thurman as Marian, where the sheriff’s mistress is her malign double.

Munday’s Marian, re-invented as a titled lady, is little more than a cipher in a world of male property: she takes to the woods, but does nothing there. Robin does apostrophize her, but only as a distant pastoral lover, with none of the direct desire or physicality of the pastourelle. Marian’s beauty is an aspect of the beauty of the forest, to be loved in entirely reified form. Robin’s finest poetry is addressed around rather than towards her:

For Arras hangings and rich Tapestrie

We have sweet natures best imbrothery.

For thy steele glass, wherin thou wontst to looke,

Thy Christall eyes, gaze in a Christall brooke.

At court, a flower or two did decke thy head;

For what in wealth we had, we have in flowers,

And what wee loose in halls, we finde in bowers.(1374-81)

In The Death of Robert Earle of Huntington, Marian occupies an essentially minor role as she mourns Robin, and is then pursued by John through most of this play: she is equally secondary, in comic mode, in the Admiral's Men's multi-authored follow-up Looke About You of 1600, where her strongest impact is when Robin borrows her nightgown and turban to appear in very bizarre disguise, and as a result is wooed by King Richard as a distinctly comic, if perhaps also homoerotic, false Marian..But woman and forest could have a more active and classical association based on the image of a Diana-like huntress. Michael Drayton, in the Sherwood section of his 1622 version of Poly-Olbion, represented her as Robin's partner:

his mistris deare, his loved Marian

Was ever constant knowne, which whersoere shee came

Was soveraigne of the Woods, chief Lady of the Game:

Her Clothes tuck'd to the knee, and daintie braided haire

With Bow and Quiver arm'd, shee wandr'd here and there

Amongst the forests wild; Diana never knew

Such pleasures, nor such Harts as Mariana slew. (26.352-8)

The mix of local figure and classical huntress would be developed in Ben Jonson's unfinished The Sad Shepherd, published in 1641. Here Marian is more than a mere possession as in Munday or a sportswoman as in Drayton. She is for once fully a lover, and Jonson pursues the classical idea of the bow and arrow in an amatorial image. As Marian returns from hunting, the forest lovers meet and exchange enthusiasm, affection and what seems like an off-color joke about the part of the deer called "the inch-pin":

Marian: How hath this morning paid me, for my rising!

First, with my sports; but most with meeting you!

I did not half so well reward my hounds,

As she hath me today: although I gave them

All the sweet morsels, Calle, Tongue, Eares and Dowcets !

All the sweet morsels, Calle, Tongue, Eares and Dowcets !

Robin: What ? And the inch-pin ?

Marian: Yes.

Robin: Your sports then pleas'd you ?

Robin: One, I do confesse,

I wanted till you came. But now I have you,

I'll grow to your embraces, till two soules

I'll grow to your embraces, till two soules

Distilled into kisses, thorough your lips

Marian: O Robin! Robin! (I. 6.1-13)

In spite of (or because of?) this frank affection Jonson strongly develops the false Marian motif with a witch called Maudlin: she is sometimes called Maud, which Jonson undoubtedly knew is the short form of Matilda, so suggesting a black/white splitting in the figure of the heroine. Maud impersonates Marian with some success, not in this case seeking personal pleasure like the Queen in Munday, but suggesting Marian is a whimsical and cruel cause of trouble: as this negative stereotype of woman, the false Marian is both elusive and aggressive, and as a result manages to confuse and alarm Robin. These problems and other complications were to be reconciled by the end, according to Jonson's surviving Act synopses.

The vigorous real Marian does ultimately defer to Robin's authority, both aristocratic and male, but she is also represented as having real agency, including physical and gendered power. Jonson's sense of Lady Marian's potential power will take centuries to re-emerge, but the gentrified heroine did cross over into two ballads. "Robin Hood and Maid Marian" appears to be a version of "Robin Hood and Will Scarlet" with Marian playing the Will role: in both cases a person enters the forest looking for Robin, fights lustily with him, they call off the fight and become close. The Will Scarlett story does have some elements of gentrification that may have invited this treatment, as Will is both Robin's cousin and from the minor gentry. But "Robin Hood and Maid Marian" is fully gentrified. In love with the outlawed Earl Robin, Marian follows him into the greenwood dressed as a man and well-armed:

With quiver and bow, sword buckler and all,

Thus armed was Marian most bold,

Still wandering about to find Robin out

Whose person was better than gold.

But Robin Hood hee himself had disguisd,

And Marian was strangely attir'd,

That they provd foes, and so fell to blowes,

Whose vallour bold Robin admir'd.

They drew out their swords, and to cutting they went,

At least an hour or more,

That the blood ran apace from bold Robins face,

And Marian was wounded sore.

"Oh hold thy hand, hold thy hand," said Robin Hood,

"And thou shalt be one of my string,

To range in the wood with bold Robin Hood,

And hear the sweet nightingall sing."

When Marian did hear the voice of her love,

Her self shee did quickly discover,

And with kisses sweet she did him greet,

Like to a most loyal lover. (1-20)

Finally they agree affectionately: though the all-male forest-based yeoman ballad has a presence at the end when Marian fits into the normal homosocial world of the forest in Will Scarlet's role—in the usual pattern, after celebrating, the yeomen stroll together in the forest, and here Robin:

went to walk in the wood,

Where Little John and Maid Marian

Attended on Robin Hood. (79-81)

There is further integration with the yeoman tradition. This is a very rare gentrified text where Lord Robin and Lady Marian do not return to their social world of wealth and position: the ballad ends:

In solid content together they livd,

With all their yeomen gay;

They livd by their hands, without any lands,

And so did many a day. (82-85)

The only other heroine-related ballad is "Robin Hood's Birth, Breeding, Valour and Marriage where he becomes the partner (and husband) of Clorinda, Queen of the Shepherds in a downmarket version of the fairy-mistress romance.

This intermittent and uncertain presence of Marian in the later ballads is shared by her representation on the eighteenth-century musical stage. In Robin Hood: An Opera (1730) Matilda is the sister of an unnumbered King Edward, and while she is devoted to the Earl of Huntingdon there is, for theatrical purposes, a rival, the wicked Earl of Pembroke. Lord Robin will eventually kill him and finally sing with his own beloved, and Matilda has a friend Marina who loves Huntington's lordly friend Darnel, who will in the forest play Little John. But a darker side of gendered theatre appears: Will Stutely, an outlaw associated with displaced lord Robin, seizes both Marina and Matilda. He plans to rape them: "You are my prisoners by the right of Armes, and I must make bold to try my Manhood upon you" (26) and the foresters feel the women could be "shar'd in Common," but Robin soon puts a stop to this brutish response to the relatively recent presence of women on the stage.

Marian/Matilda is in any case not permanent. In 1751 the Drury Lane theatre produced Robin Hood: A New Musical, where the heroine is Clarinda, from "Robin Hood's Birth," but the story is Alan a Dale's and Robin, masquerading up-to-date as Sir Humphrey Wealthy, brings about the desired match. The 1782 comic opera Robin Hood or Sherwood Forest has even more amatory activity, with Allen and Scarlet having partners, and Robin here again joins with Clarinda. Marian does return in the major 1795 production of Merry Sherwood or Harlequin Forester, but plays a very minor role, which is also true of Ritson's long Introduction, where she is mentioned once in passing in connection to Morris dancing and then in the two Munday plays as "an important character" (xx), but is only quoted when she mourns Robin's death—Ritson makes no mention of Drayton's play and poem or Jonson's masque with their vigorous representations of Marian.

4. Novel Heroine: Nineteenth Century

The eighteenth-century reticence about Marian changes as the outlaw tradition enters the novel, the genre which played such a large part in realising women's roles, both as characters and authors. The core treatment of nineteenth-century Marian, which survives to the present, is as a noble but vulnerable woman, a prime way of both enhancing and validating the status of her male consort, creating a relationship which usually falls short of any serious emotional or sensual interchange. Before the novel begins its work some aspects of both feeling and physicality for Robin and even Marian are evoked through Romanticism in the poetic exchange of early 1818 between Reynolds and Keats. The first sonnet Reynolds sent Keats is almost entirely masculine, focusing on "the archer-men in green" until the final word, where "Marian" seems an afterthought to produce a slightly forced rhyme:

Feasting on pheasant, river fowl and swan,

With Robin at their head, and Marian. (151)

In terms of attention at least, the second sonnet makes up for this, moving in the second quartet on to the lady:

and near, with eyes of blue

Shining through dusk hair, like the stars of night,

And habited in pretty forest plight,—

His green-wood beauty sits, young as the dew.

His green-wood beauty sits, young as the dew.

Oh, gentle-tressed girl! Maid Marian!

That stray in the merry Sherwood: thy sweet fame

Can never, never die. (151)

The physicality of Romanticism, as well as its sexist use of woman as an object to admire, is evident: her "sweet fame" is a merely girlish honor.

However, in his poem in response to Reynolds' two sonnets, Keats does involve Marian in a form of action, and even imagines she might have a voice. Just as Robin will regret what has happened under mercantile imperialism to his beloved oaks, so she will have a political response to a bleak feature of the present world:

And if Marian should have

Once again her forest days

…

She would weep that her wild bees

Sang not to her—strange! that honey

Can't be got without hard money! (46-48)

Once again her forest days

…

She would weep that her wild bees

Sang not to her—strange! that honey

Can't be got without hard money! (46-48)

Also, in his farewell Keats pays equal respect to both characters:

Honour to bold Robin Hood,

Sleeping in the underwood!

Honour to maid Marian,

And to all the Sherwood-clan ! (57-60)

While Reynolds clearly learned from Keats' responses in his final sonnet, it has no reference to Marian and the only gender-related item is a reference to the impact of Robin Hood bringing "A dazed smile on cheek of border lass" (151).

Leigh Hunt's treatment is more understandably without Marian. His four ballads focus on reworking the politically-oriented ballad yeoman, and so she is absent, though the post-1855 revision inserts into the final ballad "How Robin Hood and his Outlaws Lived in the Woods" two stanzas about Marian, who with Robin "reign'd as pleasant to all, As faithful to each other" (5.342). Through this late addition Hunt can be acknowledged as having some limited sense of the role of Robin's partner in life, but only Keats has imagined this in any detail.

The existence of such a figure is recognized, but not as Marian, in the almost always ignored first outlaw novel, Robin Hood: A Tale of the Olden Time of 1819, appearing just as Scott was working on Ivanhoe. The heroine is Ruthinglenne: she loves Robin, goes to the forest to meet him, has difficulties, is brave, does her best to help him in his own problems, and is finally reunited with him to share his life and elevated social status. It is like a parallel, or even parody, of the Marian story found in Munday, but the name Marian is never used and the whole story is made more Gothic by her having to hide in a nunnery and marrying Robin while pretending to be her twin sister.

Two major writers produced Robin Hood novels soon afterwards. Peacock was at work in autumn 1818, but did not finish and publish until early 1822. Scott's Ivanhoe, out for Christmas 1819, represented one Marian option by not mentioning her at all in the context of Robin as a fierce yeoman. Peacock offers a lively version of the Munday tradition, condensing it with a range of ballad stories. This version went immediately onto the stage with book by J. R. Planché, and music by Henry Bishop (using Peacock's own songs) and played all through the century, and apparently as a result Marian would appear regularly in the pantomimes and grandiose operettas that flourished through the century.

Peacock's version has become either directly or indirectly the default Marian. His heroine is capable of vigorous action and strong values, but is also foreclosed by the masculine world. She does have point of view, but Robin comes to control it; she can shoot, and fight, but she needs rescuing in a crisis; she is lovely and vital, and an object of desire for Prince John's follower Sir Ralph Montfaucon, a good fighter and quite noble kind of man—but his rivalry with Robin invites analysis in terms of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's ground-breaking book Between Men. Marian is in this way made both a subject in her own right and the potential object of a foregrounded, and complex, male desire. In the same way Peacock's prose both privileges and gazes at its heroine:

Matilda, not dreaming of visitors, tripped into the apartment in a dress of forest green, with a small quiver by her side and a bow and arrow in her hand. Her hair, black and glossy as is the raven's wing, curled like wandering clusters of dark ripe grapes under the edge of her round bonnet; and a plume of black feathers fell back negligently above it, with an almost horizontal inclination, that seemed the habitual effect of rapid motion against the wind. (26)

This is the first work in the Robin Hood tradition where Marian is given the title of the work in which she appears. Peacock was an admirer of Mary Wollstonecraft and friend of her daughter Mary Shelley, and the strength of attention devoted to Marian through the novel justifies her providing the title. She is witty, active, brave, charming and beautiful, and the text seems to read her in something like that order. It seems likely that Peacock was to some degree modelling her on the highly dynamic Mary Shelley, whom he had seen a good deal in the year before starting the novel.

In the early action Marian, as Matilda, dominates, resisting her father with spirit and wit, and entrancing Sir Ralph. Brother Michael says she has "beauty, grace, wit, sense, discretion, dexterity, learning and valour" (14). For a while Matilda remains trapped at home and is pestered by Prince John, who besieges Arlingford to take her. The baron, a sort of Tory radical, burns his castle so John cannot use it, and Matilda, renamed by Brother Michael as Marian, escapes to the forest and accepts the post of queen. Hero and heroine are imagined in positive natural terms. Brother Michael sings of them being "like twin plants of the forest and [they] are identified with its growth" (34). She and Robin marry, but under the forest code of behavior she will remain a maid; she helps and supports people, but can be active too, fighting well when she, Robin, and her father are attacked in a hut by the sheriff's men.

The potent model Peacock offered of Marian was not automatically adopted by novelists who took up the story. Early contenders, Thomas Miller with Royston Gower (1838) and G. P. R. James in Forest Days (1843), weave Marian-free medieval fables with reference to modern politics, respectively radical and liberal, but she does appear in the popular Robin Hood and Little John, or The Merry Men of Sherwood Forest by Pierce Egan the Younger (1840).

Here Robin is fostered on a forester in Sherwood and rescues the young Marian Clare, with her "choice mouth," "large dark hazel eyes," and "small-white-tapered hand, the softest of the soft" (19). Only fourteen, he loves Marian, and after six years pass defeats Sir Hubert de Boissy, a rival for her. They declare for each other, but she is kept out of the ensuing action, mostly violent, but eventually they marry and are said to have a son, but Marian does not develop at all as a mother, merely remaining the threatened and eventually tragic heroine. When King John's men attack the forest she dies with Robin beside her, and after his death at Kirklees he is buried back in Sherwood beside Marian.

Joachim H. Stocqueler answered Egan’s title with his Maid Marian, the Forest Queen (1849). Acting as leader of the outlaw band while Robin is on crusade, with Little John as her "trusty lieutenant" she "paraded her men and inspected their appointments" (36), but after she is gored by a wild boar in a distinctly sadistic scene, the villainous Hugo Malair abducts her in a sack. When Robin returns from crusade with two Arabs, Suleiman and his dancing-girl daughter, Marian begins to be jealous of Leila with Robin, but she vanishes to an orientalist fate as Prince John's mistress. In later action Marian is taken prisoner and rescued when Robin shoots a silken ladder into her cell. Stocqueler sums up briskly, bypassing Robin's death for the fate of his title's heroine, being, as in Munday, poisoned by Prince John and buried at Dunmow.

In the next major saga, George Emmett's Robin Hood and the Outlaws of Sherwood Forest (1869), Marian is a Saxon of "wondrous loveliness" (63), niece to Much the Miller, a hard-working tradesman. She is again the vulnerable heroine, harassed by the sheriff and then abducted by the king's men, but escapes by shooting a man with a crossbow. Later she is abducted again, to Brittany, and some of the ballad "Robin Hood's Fishing" is used to rescue her: the end is curiously casual—after Robin's death Little John buries him and simply leaves, despairing of seeing Marian again.

The Marian-free ballad tradition was re-energized, especially in America, in Howard Pyle's The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883): the only reference to the heroine is that early on Robin thinks of "Maid Marian and her bright eyes" (3). But Marian survives in the popular novel tradition, as in Edward Gilliats' In Lincoln Green (1897), where as a "buxom young woman" with "flaxen hair" (8) she gives Robin a son and a daughter and they all live happily. In Maid Marian and Robin Hood (1902) by Joyce Muddock (the real name of a male popular author) a blonde Saxon beauty “deeply skilled in woodland lore” (25), Marian helps free Robin from execution, eventually joins him and they marry, she becoming "a true wood nymph" (187); but, angry because of Robin's rash daring, she leaves the forest, has dire misadventures and finally her Norman lover brings her and Robin together to die.

The influential Robin Hood and His Merry Men (1912) by Henry Gilbert returned to the mainstream, being based largely on ballad action, with Marian often marginal to the action. She joins Robin rarely in the forest and when King Richard returns they marry and live on her inherited lands for sixteen years. That approach resumes Tennyson's The Foresters (written by 1881), where Marian is treated with considerable respect as a secondary and helpful figure, accepting, as Robin specifies, the role of ideal woman Guinevere refused to play:

The high Heaven guard thee from wantonness

Who art the fairest flower of maidenhood

That ever blossom'd on this English isle.(753)

Though Tennyson's Marian does have some energy, it is no more than ethical and charitable. She finally speaks in the plural of what they have achieved, claiming some joint agency, but the only name mentioned is that of her lord and husband:

And yet I think these oaks at dawn and even

Or in the balmy breathing of the night

Will whisper evermore of Robin Hood.

We leave but happy memories to the forest.

We dealt in the wild justice of the woods.

All those pale serfs whom we have served will bless us,

All those pale mouths which we have fed will praise us

The widows we have holpen pray for us

Our Lady's blessed shrines throughout the land

Be all the richer for us. (p. 782)

The Georgian poets followed a largely Marian-distant path, though the outlaw myth did engage their somewhat mystical and distinctly homosocial interests. The cast-list of J. C. Squire's 1928 play Robin Hood sees Marian as "Rosalindish, vivacious, but more daring and male." Alfred Noyes' well-known anthology poem "Sherwood" does not mention Marian, nor, but for a passing reference, does John Drinkwater's rather elegant masque-like play Robin Hood and the Pedlar (1914), but Noyes's verse play Sherwood (1908, revised 1926) activates her through its basic use of the Munday story. The red-haired Lady Marian marries Robin but within months, surrounded by fey forest spirits rather than outlaw action, they are dying together and then reappear as embodied spirits in a love and death ending of antique Romanticism.

In early film the image of Marian common to both novels and Romanticism as a faithful vulnerable wife can become transmuted into a flapper-like spirited young woman, a medievalist Pauline in Peril. This continues in the children's fiction Marian, the Hollywood lady and up to the heroine of the 1984 Robin of Sherwood television series, with a Laura Ashley-style Marian, with big eyes and waves of hair, but occasionally endowed with second sight.

Robin's lovely vulnerable partner could at times become a little more steely. In the 1922 Douglas Fairbanks film she is at first negatively so as "The Queen of Beauty" who frightens the boyish Robin, a sort of super-Marian rather than a false one, but after he rescues her from Prince John they bond in common interest, rather than love. Later she assumes a more positive strength, calling Robin back to save his country, and fakes her own death to save herself—at which point he does move on to loving her. In the 1938 film starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland not only wore dresses of apparently rigid satin but also was capable of some management to help her man. The very successful and, at least in its theme-song, unforgotten, television series starting in 1955 had a Marian played at first by the handsome, straight-speaking, Bernadette O'Farrell, who was replaced for the final third of the episodes by another Irishwoman, Patricia Driscoll, a little less formidable—but both of them were to pale before the growing strength of Marian in later decades.

5. Marian in Charge: Late 20th - 21st Centuries

The first invigorated Marian was Audrey Hepburn in Robin and Marian of 1976. A nun, who is wiser and calmer than the limited, soldier-like Robin and Little John, she, knowing his wound will incapacitate him, decides they should die together from drinking a potion she provides—the Prioress is redeemed. Elements of agency were visible in the two major Robin Hood films made in 1991. In Robin Hood: The Prince of Thieves the first view of Marian is in armor fighting Robin: finally she hits him in the groin. However, this opening aggression fades by the end of the film she is as usual imprisoned and in need of rescue, and ends in a highly stereotypical gender position, as the novel of the film puts it:

He took Marian into his arms, and for a long moment they stood together, losing themselves in each other. Marian raised a trembling hand to Robin's face, as though half-afraid he might disappear like a dream.

"You came for me ! You are alive!"

Robin held her eyes with his. "I would die, before I let another man have you."

They kissed as if they were never going to stop. (232-33)

The 1991 Patrick Bergin-as-Robin film had a more dynamic Marian in Uma Thurman. From the start she admires knowingly the handsome Robin, and then when disguised as a boy, herself frustrates the false Marian, and, still a boy, plants a warm and initially gender-disruptive kiss on Robin's mouth. Yet she too fades into stereotype, saying of Robin, before their final marriage "he makes the bees buzz in my breast."

It is in the novel genre that the notable feminist moves have been made. Some children's writers have given Marian substantial roles like the omni-competent heroine created by the historian Carola Oman in 1939, Antonia Fraser's Marian both adventurous and vulnerable (including to the false Marian of Black Barbara) in 1955 or Bernard Miles's more recent (1979) robust semi-feminist tomboy. A serious attempt to represent Marian differently was Robin McKinley's The Outlaws of Sherwood (1988), where the well-born lady visits Robin in the forest and wins the archery tournament disguised as him. A shift towards Marian as central figure is indicated in the title of Jennifer Roberson's novel Lady of the Forest (1992). Her father, dying on crusade, wanted her to marry the Sheriff for protection; she comes to love Robin, but the Sheriff is not an ogre, and is difficult to avoid—yet eventually she becomes Robin's very energetic supporter.

Gayle Feyrer's The Thief's Mistress (1996) marks a new stage in Marian's renovation both by making her a serious and successful fighter and also by engaging her in the contemporary taste for overt violence and sexuality. Sir Guy is handsome and decisive: Marian decides to take him as her lover and some steamy scenes ensue. But she does not forget Robin and though she pulls a knife on him, they feel "a strange bond of desire": (250). Theresa Tomlinson liberates Marian in a different direction in her serious-toned juvenile novel The Forestwife (1993), developed into a trilogy (also called The Forestwife) with Child of the May (1998) and The Path of the She Wolf (2000). Marion Holt escapes a forced marriage into the forest, and becomes the Forestwife, offering advice and support to poor women, and gaining the help of a handsome but limited peasant—Robin.

The most self-conscious moves towards film feminism have been made through comedy, which implies euphemization of the theme. In The Zany Adventures of Robin Hood (1984), a less than heroic Robin (George Segal in ill-fitting green tights) has a Marian out of Valley of the Dolls, played to the hilt by Morgan Fairchild, and about as feminist as the wishful wrigglings of Amy Yasbeck as Marian in Mel Brooks' Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993).

Another comically contained version of Marian's frustrations appears in Robin Hood: A High Spirited Tale of Adventure (1981), a Muppet production in comic book, not film, form. Robin is "a bold and chivalrous frog" (18) who is seized by Sheriff Gonzo. But there is hope: "Maid Marian was in truth an extremely glamorous pig who had fallen in love with Robin Hood and had come to live in the forest to cook and sew for her frog and his merry men (18)." Leading a band of courageous chickens—the sight of them unmans Gonzo—she rescues Robin. The Muppet version satirizes equally forceful females and feeble Robin Hood plots, but another project aimed primarily at children put Marian more fully in charge, though also in a farcical and diminishing context. The BBC television series of 1988, challengingly titled Maid Marian and Her Merry Men, placed her, played vigorously by Kate Lonergan, in charge of a rag-bag of dissidents among whom the last and definitely least is a fragilely handsome dress-designer named Robin of Kensington. With her sleeves rolled up, Marian organizes their victories, but in a context so improbable and with plotting so ludicrous that any possibilities of a feminist effect are heavily carnivalized.

In more recent visual versions, Marian's capacity for agency is assumed, but not of prime interest. In The New Adventures of Robin Hood (1997) a posturing matinee-idol Robin has as partner a busy, stocky Marian, dressed usually in leather shorts and skimpy blouses, downstream from Xena the Warrior Princess. Differently lurid was Disney's Princess of Thieves (2001) where the young Keira Knightley played Gwyn, daughter of Robin Hood, who leads a geographically very improbable resistance against bad Prince John and ends up as willing mistress to an invented King of England, Philip I.

A more serious updating of the story and of Marian was involved in the BBC television series Robin Hood starting in 2006. Robin returned from crusade in disgruntled, apparently post-Iraq, mood; Lady Marian, the daughter of a former sheriff of Nottingham, initially feels Robin's outlawry is self-indulgent and he should work within the system. But she is also highly active, in part by miming Robin as "The Night Watchman" delivering food and help to the poor, and also, as in the feminist novelists, by becoming somewhat involved with the older and semi-criminal Guy of Gisborne. Brisk and handsome rather than vulnerable and glamorous, Lucy Griffiths plays both a figure for modern times, and one like Robin and his friends aimed primarily at a young teenage audience.

The polyvalent young Marian of this series may have led the producers of the 2010 film Robin Hood to cast the worldly-wise gamine Sienna Miller as Marian, but by report Russell Crowe, playing Robin, felt the difference in age would be embarrassing, and Marian was eventually played by Cate Blanchett as a mature, almost plain, and deeply earnest woman. She supports Robin in his move towards early popular representation, but lacks the flamboyant energy of modern feminist Marians: both the social and the gender politics look back to nineteenth-century fiction.

After her long journey through trivialization, anonymity and instrumentality, the liberated Marian has some way to go. At the moment, the regendering of the Robin Hood legend seems unfinished business—it would not be difficult to imagine a feminist version of the outlaw story going far beyond the recent nervously comic ventures, and seriously developing existing Marian-liberating fiction. Along the way to the present possibilities, there have been some high points, as in the self-management of the pastourelle heroine, the bravura of Jonson's Marian, the dazzling capacity of Peacock's heroine; and Marian's moves into modern mature independence.

But whatever does come up in the way of new Marian fictions, it is still very unlikely that from now on her role will be as absent or insignificant as it was before the impact of generic change and feminist thinking began the outlaw heroine on her long, slow, and still uncertain progress towards a position and an impact as important as that of her consort.

Read Less

Bishop, Henry Rowley (1786 - April 30, 1855)

Chesson, Nora (1871 - 1906)

Daniel, George (1789 - 1864)

Emery, Clayton (b. 1953)

Jonson, Ben (c. 1572 - 1637)

Keats, John (1795 - 1821)

The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997 (Editor)

Excerpts from The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and Maid Marian - 1997 (Editor)

Excerpts from The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and Maid Marian - 1997 (Editor)

Munday, Anthony (1553 - 1633)

The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997 (Author)

Excerpts from The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997 (Author)

Excerpts from The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997 (Author)

The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and Maid Marian - 1997 (Editor)

Robin Hood and Maid Marian - 1997 (Editor)

Planché , James Robinson (1796 - May 30, 1880)

Reynolds, John Hamilton (1794 - 1852)

Waldron, F. G. (1744 - 1818)

Weelkes, Thomas (1576 - 1623)

The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997

by Anthony Munday (Author), Stephen Knight (Editor), Thomas H. Ohlgren (Editor), Russell A. Peck (Editor)

by Anthony Munday (Author), Stephen Knight (Editor), Thomas H. Ohlgren (Editor), Russell A. Peck (Editor)

Excerpts from The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington - 1997

by Anthony Munday (Author), Stephen Knight (Editor)

by Anthony Munday (Author), Stephen Knight (Editor)

Maid Marian; or, Huntress of Arlingford - 1822

by James Robinson Planché (Author), Henry Rowley Bishop (Composer)

by James Robinson Planché (Author), Henry Rowley Bishop (Composer)

Robin Hood and Queen Katherine (Child Ballad No. 145A) - 1882-1889

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

by Anonymous (Author), Francis James Child (Editor)

Thomas Bewick (1753 - 1828)

F. W. Fairholt (c. 1813 - 1866)

Sir Amédée Forestier (1854 - 1930)

Louis Rhead (1857 - 1926)

N. C. Wyeth (1882 - October 19, 1945)

Thomas Bewick (1753 - 1828)

Robin Hood and Maid Marian1795

F. W. Fairholt (c. 1813 - 1866)

Matilda Fitzwalter's Tomb1847

Maid Marian1847

Robin Hood's Garland Woodcut1847

Maid Marian

A Facsimile from the Original Edition, Headpiece to...1847

Sir Amédée Forestier (1854 - 1930)

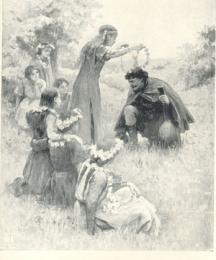

Then she took the daisy-chain that she was wearing...1898

Louis Rhead (1857 - 1926)

Maid Marian1912

Robin Hood and Marian in Their Bower1912

Chapter 20 Heading1912

And Soon They Were Forced to Part1915

N. C. Wyeth (1882 - October 19, 1945)

Robin Meets Maid Marian1921

Images Gallery

And Soon They Were Forced to Part1915

Chapter 20 Heading1912

A Facsimile from the Original Edition, Headpiece to...1847

Maid Marian1912

Maid Marian1847

Maid Marian

Matilda Fitzwalter's Tomb1847

Miss Julian as Maid Marian19th century

Robin Hood and Maid Marian1795

Robin Hood and Marian in Their Bower1912

Robin Hood's Garland Woodcut1847

Robin Meets Maid Marian1921

Then she took the daisy-chain that she was wearing...1898