The Questing Beast (also called the Bizarre Beast or the Beste Glatisant) appears briefly in French and English medieval texts. In French, it appears in three thirteenth-century texts – the Prose

Tristan,

Perlesvaus, and the Post-Vulgate cycle.

1 In English, it appears in Malory’s fifteenth-century

Morte D'Arthur. The creature's name comes not entirely from its function (as the object of quests) but from the monstrous barking noise it makes. In French and in Middle English,

glatisant means barking or baying, while in Middle English, the verb

questen means to bark as well as to hunt. This double meaning of the English word makes the Questing Beast's name a pun; it is the barking beast for which knights hunt. In both Malory and the Post-Vulgate, the noise it produces is similarly described as "lyke unto the questyng of thirty coupyl houndes, but all the whyle the beest dranke there was no noyse in the bestes bealy" (Malory 42). In several accounts of the Questing Beast, this noise is caused quite literally by the barking of dogs inside the beast's belly (

Perlesvaus 154,

Lancelot-Grail 5.284). Though the medieval texts provide various physical descriptions of the Questing Beast, the barking or yelping noise that emerges from its insides is consistently used to describe the creature.

The Questing Beast's physical form differs radically depending on the text in question. In Perlesvaus, the Questing Beast appears when Perlesvaus (commonly called Perceval in English and most other French texts) sets out in search of the Grail, and it is "as white as new fallen snow, bigger than a hare but smaller than a fox" (154). However, despite the beast's relatively

...

Read More

Read Less

The Questing Beast (also called the Bizarre Beast or the Beste Glatisant) appears briefly in French and English medieval texts. In French, it appears in three thirteenth-century texts – the Prose

Tristan,

Perlesvaus, and the Post-Vulgate cycle.

1 In English, it appears in Malory’s fifteenth-century

Morte D'Arthur. The creature's name comes not entirely from its function (as the object of quests) but from the monstrous barking noise it makes. In French and in Middle English,

glatisant means barking or baying, while in Middle English, the verb

questen means to bark as well as to hunt. This double meaning of the English word makes the Questing Beast's name a pun; it is the barking beast for which knights hunt. In both Malory and the Post-Vulgate, the noise it produces is similarly described as "lyke unto the questyng of thirty coupyl houndes, but all the whyle the beest dranke there was no noyse in the bestes bealy" (Malory 42). In several accounts of the Questing Beast, this noise is caused quite literally by the barking of dogs inside the beast's belly (

Perlesvaus 154,

Lancelot-Grail 5.284). Though the medieval texts provide various physical descriptions of the Questing Beast, the barking or yelping noise that emerges from its insides is consistently used to describe the creature.

The Questing Beast's physical form differs radically depending on the text in question. In Perlesvaus, the Questing Beast appears when Perlesvaus (commonly called Perceval in English and most other French texts) sets out in search of the Grail, and it is "as white as new fallen snow, bigger than a hare but smaller than a fox" (154). However, despite the beast's relatively small size, "she bore a litter of twelve in her belly which were yelping like a pack of dogs" (154). The dogs inside it frighten and torture the beast, and once the whelps are born, they rip the Questing Beast to pieces (154). Here, the Questing Beast serves a clear allegorical function; Perlesvaus's uncle explains that the Questing Beast is a figure of Christ, who is chased by the twelve tribes of Israel (166). Although within Perlesvaus the Questing Beast possesses a specific meaning, its symbolism is left vague (at best) in other medieval works in which it appears.

In the Post-Vulgate's Suite du Merlin and Queste del Saint Graal, the Questing Beast is given almost no physical description. At its first appearance, it is described only as "a very large beast, the most bizarre of form ever seen, as strange of body as of conformation and as strange inside as outside" (4.167-8). Yvain, Galahad, and Girflet see the Questing Beast while on the Quest for the Holy Grail; Yvain chases it for a time (5.139), and Galahad and Bors also pursue it (5.145). When Galahad and Bors meet Palomides and his father Esclabor, Esclabor tells the story of how eleven of his sons were destroyed by the Questing Beast, leaving only Palomides to pursue it (5.147). Watched by Galahad and Perceval, Palomides kills the Questing Beast in the Post-Vulgate cycle. He wounds it with a lance, and it cries out and vanishes into a deep lake. The lake "began to throw and shoot forth... flames," and it continues to boil once the beast has died in the water (5.278). The Post-Vulgate also provides an origin for the creature; it is born from a young woman who falls in love with her brother. When the brother rightfully rejects her inappropriate love, the woman plots with the devil to have him killed. In exchange for the devil's help, she sleeps with the demon and conceives. When her brother is accused of raping her and condemned to death, he curses her, and as a result she gives birth to the Questing Beast. This origin also explains the bizarre barking that comes from the Questing Beast's belly; because the woman's brother is killed by a pack of dogs, the Questing Beast's noise reminds those who encounter it of the unjust death of the young man (5.284-85).

The Prose Tristan's account of the Questing Beast is very similar to the account in the Post-Vulgate. The Prose Tristan retells the Questing Beast's origins as a creature born from a young woman and a devil. However, unlike the Post-Vulgate, the Prose Tristan does provide a physical description of the beast. This description is radically different from the one presented in Perlesvaus; here, the Questing Beast has a stag's feet, a serpent's head, a leopard's body, and a lion's thighs and tail.

In Malory, the Questing Beast's physically hybrid appearance is again described; Malory's portrayal follows the Prose Tristan, where the creature is an amalgamation of animals and its strange barking noise heralds its arrival (484). The Questing Beast's origin is not retold in the Morte, where it first appears to Arthur after Mordred's conception. Alexander Bruce suggests that when the Questing Beast appears in Malory, it "symbolizes that a relationship between people is not right, that two elements which should have remained separate have been mixed, and that chaos will result from the unnatural situation at hand" (133). In this way, it becomes associated with the tragedy of Malory's work. However, the Questing Beast is most commonly associated with Palomides. For example, when Tristan is out hunting and sees the Questing Beast, "he put on his helme, for he demed he sholde hyre of sir Palomydes; for that beste was his queste" (683). Where the Questing Beast goes, Palomides quite literally follows, and Palomides emphasizes his connection to the beast by placing its image on his shield (656) or calling himself "the knyght that folowyth the Glatysaunte Beste" (590). Bruce suggests that Palomides is associated with the Questing Beast in Malory because the knight is himself a hybrid creature, a mixture of Saracen and virtuous knight, just as the beast is a physical crossbreed (138).

Critics have suggested varied sources for and explanations of the Questing Beast. Antonio L. Furtado, who argues that the Questing Beast serves as an allegory of the end of Arthur's kingdom, has linked it to the Beast of the Book of Revelation (40). In contrast, Helmut Nickel sees a similarity between the accounts of the Questing Beast and the Gesta Regum Anglorum of William of Malmesbury, which tells the tale of King Edgar's dream "of a bitch whose whelps could be heard barking in her womb" (66). Yet for some critics, the Questing Beast defies interpretation. Catherine Batt has suggested that the Questing Beast does not have a clearly defined function in Malory's narrative, but rather, it is "a series of signifiers without the satisfaction of ultimately recovering an intelligible meaning" (152). Malory describes the Questing Beast as "a full wondirfull beyste and a grete sygnyfycasion; for Merlyon propheseyed muche of that byeste" (717). However, Batt points out that its importance is never really explained in Malory's work as it is in the Post-Vulgate cycle (153). Merlin's prophecies about the Questing Beast are never mentioned again, and its great meaning is never made explicit. In effect, the Questing Beast invites interpretation while evading explanation; thought critics pursue its meaning, no consensus on the creature has been reached.

Modern reimaginings of the Questing Beast serve various functions. The Questing Beast is adapted by T. H. White in his The Once and Future King, where it functions primarily to create humor. White also provides an explanation for Palomides's pursuit of the Questing Beast. In White’s version, an inept Pellinore chases the beast for seventeen years before he is lured away from the hunt by Sir Grummore. The beast becomes sick from the lack of attention or, as Pellinore explains, because it needs someone “to take an interest in it” (161). Pellinore nurses the beast back to health and begins to chase it once more. Later, when Pellinore has abandoned the hunt again and become depressed, Palomides and Grummore disguise themselves as the Questing Beast to cheer Pellinore. The Beast falls in love with the disguised Palomides, and so Palomides takes up its pursuit (329).

Most modern appearances of the Questing Beast emphasize Palomides's pursuit of it rather than Pellinore's quest or Arthur's encounter. In Ælian Prince's Of Joyous Gard (1890), Palomides sets out after the Questing Beast, rather than the Holy Grail, after his baptism. This alternate quest emphasizes Palomides's previously Saracen status even once he has become Christian and leaves Palomides markedly different from his peers. William Morris's poem, "Palomydes' Quest" (1855), is told from the point of view of Palomydes, who considers the praise and recognition he will receive when he conquers the Questing Beast. However, while riding through the forest, Palomydes recognizes that even achieving the Questing Beast will not earn him Iseult's love. The pursuit of the Questing Beast thus emphasizes the impossibility of Palomydes's quest for Iseult.

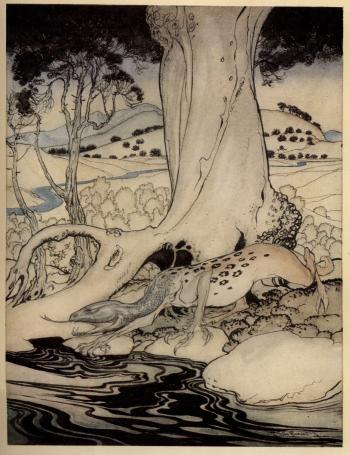

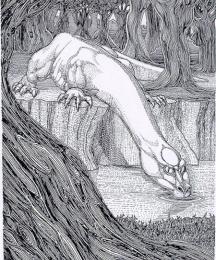

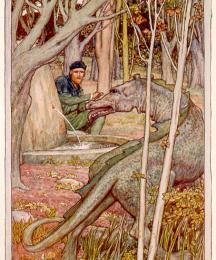

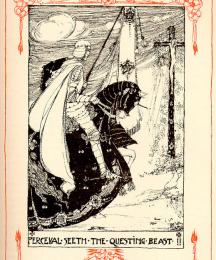

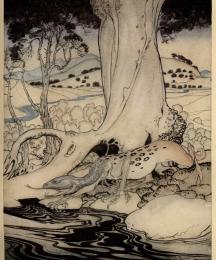

In addition to these literary revisions, the Questing Beast lends itself to visual reinterpretation. Jessie M. King's "Perceval Seeth the Questing Beast" (1903), which accompanies a translation of Perlesvaus, depicts the Questing Beast as a small, solid-colored creature almost like a rabbit. The beast, at the foot of a cross, glances back at Perceval. However, most artists' portrayals of the Questing Beast are illustrations of Malory. In his illustration, Aubrey Beardsley portrays the Questing Beast with long, dark claws and spots that look almost like scales in a work titled "How King Arthur Saw the Questing Beast and Thereof Had Great Marvel" (1893). Despite its proximity to him, Arthur has not yet noticed the Questing Beast creeping to the water. H. J. Ford's "Arthur and the Questing Beast" (1902) depicts the beast's first appearance in Malory. Arthur, sword drawn, glances at the beast as it creeps between trees to drink from the water. Arthur Rackham's illustration, titled simply "The Questing Beast" (1917), depicts the beast in isolation, drinking from the river. The muted color makes the fabulous creature look natural in the landscape surrounding it in spite of its peculiar hybrid form; the beast's serpent-like head is roughly the same color as the mountains behind it, and the browns of its body blend into the trees around it. Anna-Marie Ferguson creates a similarly naturalistic Questing Beast (2000). In her portrayal, the Questing Beast's disparate body parts blend smoothly, united by the orange and yellow tones she uses. Her Questing Beast is near water, and its body blends into the foliage at the riverbank (facing page lxiv). The Questing Beast has also appeared on television in the BBC's Merlin (2008), where it is depicted in its traditional serpent-headed form. In the episode, entitled "Le Morte d'Arthur," the Questing Beast bites Arthur while he is out hunting. The rest of the episode recounts Merlin's quest to save Arthur's life.

Mysterious to critics and appealing to artists, the Questing Beast has become iconic enough to earn a lasting place in the Arthurian tradition. While it is almost never the sole focus of a work, it remains a consistent element in both medieval and modern Arthurian works.

Footnotes1 The Post-Vulgate cycle is an anonymous cycle of thirteenth-century French romances. While it seems to be based on the Vulgate (or Lancelot-Grail) cycle that was written slightly earlier, the Post-Vulgate cycle does not include a Lancelot romance and is more heavily focused on the Grail story. For further information, see Norris J. Lacy's preface to the

Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation.

BibliographyBatt, Catherine. “Malory’s Questing Beast and the Implications of Author as Translator." Medieval Translator (1989): 143-66.

Bruce, Alexander. “The Questing Beast in Malory’s Morte Darthur.” Proceedings of the PMR Conference 19-20 (1997): 133-142.

Furtado, Antonio L. "The Questing Beast as Emblem of the Ruin of Logres in the Post-Vulgate." Arthuriana 9:3 (1999) 27-48.

The High Book of the Grail : A translation of the Thirteenth Century Romance of Perlesvaus. Trans. Nigel Bryant. Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1978.

Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation. 5 vols. Ed. Norris J. Lacy. New York: Garland Publishing, 1993-1995.

Malory, Thomas. The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. 3 vols. Ed. Eugène Vinaver. Rev. P. J. C. Field. 3rd edn. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

----. Le Morte D'Arthur. Ed. John Matthews. Illus. Anna-Marie Ferguson. London: Cassell & Co, 2000.

Morris, William. "Palomydes' Quest." The Collected Works of William Morris: With Introductions by His Daughter May Morris. Vol. 24. London: Longmans Green and Co., 1915. Pp. 70-71.

Nickel, Helmut. "Three Notes: Who Was Eslit? What Kind of Animal Was the Questing Beast? Black Against White: What Color Was King Arthur's Horse?" Arthuriana 14:2 (2004) 64-72.

Prince, Æian. Of Joyous Gard. London: E. W. Allen, 1890.

West, G. D. French Arthurian Prose Romances: An Index of Proper Names. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1978.

White, T. H. The Once and Future King. New York: Putnam, 1958.

Read Less