The bestiary tradition explicitly compares lions to Christ. In

Physiologus, for example, two attributes of lions are described that link lions to Christ; first, the lion covers its tracks with its tail to evade hunters just as Christ hid His divine nature from those who did not believe in him. Second, lion cubs are born dead and are guarded by their mothers for three days, after which their fathers breathe on them and they wake up. This resurrection after three days of death, then, mirrors Christ's resurrection (3-4). While these attributes are not included in lions' appearances in medieval Arthuriana, the connection between the lion and Christ is present. In the Prose

Lancelot, King

Arthur has a dream of a lion in water. A wise man is able to interpret the dream for him and tells him that the lion represents God, particularly Jesus. The man explains that just as the lion is the king of beasts, so God is the king of all things (2.123).

While this religious symbolism of lions is explored in medieval Arthuriana, lions in these texts often function as a marker of nobility rather than divinity.

Galahad is called the great lion (Lancelot-Grail 3.162), and Arthur is sometimes figured in prophetic dreams as a crowned lion (Lancelot-Grail 2.250,

Prose Merlin 239). The most extended connection between a lion and a character appears in Chretién's

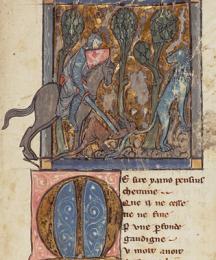

Yvain, in which the title character encounters a dragon (or a fire-breathing serpent) fighting a lion;

Yvain assists the lion in the fight, as the "more natural" creature. Yvain successfully slices the serpent in pieces, though he...

Read More

Read Less

The bestiary tradition explicitly compares lions to Christ. In

Physiologus, for example, two attributes of lions are described that link lions to Christ; first, the lion covers its tracks with its tail to evade hunters just as Christ hid His divine nature from those who did not believe in him. Second, lion cubs are born dead and are guarded by their mothers for three days, after which their fathers breathe on them and they wake up. This resurrection after three days of death, then, mirrors Christ's resurrection (3-4). While these attributes are not included in lions' appearances in medieval Arthuriana, the connection between the lion and Christ is present. In the Prose

Lancelot, King

Arthur has a dream of a lion in water. A wise man is able to interpret the dream for him and tells him that the lion represents God, particularly Jesus. The man explains that just as the lion is the king of beasts, so God is the king of all things (2.123).

While this religious symbolism of lions is explored in medieval Arthuriana, lions in these texts often function as a marker of nobility rather than divinity.

Galahad is called the great lion (Lancelot-Grail 3.162), and Arthur is sometimes figured in prophetic dreams as a crowned lion (Lancelot-Grail 2.250,

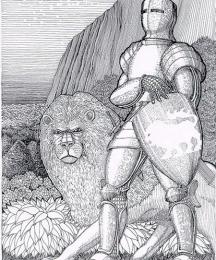

Prose Merlin 239). The most extended connection between a lion and a character appears in Chretién's

Yvain, in which the title character encounters a dragon (or a fire-breathing serpent) fighting a lion;

Yvain assists the lion in the fight, as the "more natural" creature. Yvain successfully slices the serpent in pieces, though he has to remove just a bit of the lion's tail to free it from the serpent's head. Upon finding itself freed, the lion "stood on his hind legs, stretched out his forepaws together to the knight, and bowed his head to the ground" to pay homage to Yvain (297). The lion then becomes Yvain's companion in his travels and in battle for the rest of the romance. The two become close as they travel; Yvain refuses to enter a fortress without his lion, and the sight of the lion wounded by treacherous knights drives Yvain on to "wreak revenge" on those who injured the creature (311). The lion, then, becomes one means by which others identify Yvain – the romance is also called

The Knight With the Lion - but it also marks his own nobility of character. A similar story is told in the "Owain" tale in

The Mabinogion as well as in other versions of the Yvain story, such as

Yvens saga.

The Middle English translation of Yvain's story,

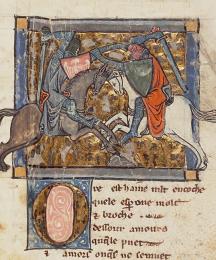

Ywain and Gawain, shares the major elements of the lion plot with its French source. Ywain encounters a lion fighting a dragon and intervenes. As in Chretién's

Yvain, because Ywain has helped the lion, the lion becomes his trusted companion (135). Throughout the rest of the romance, the lion helps Ywain in battle; other knights often comment that this is not fair, but the lion cannot be swayed from his task. The lion breaks out of various restraints to come to Ywain's aid when fights are going badly for his knight. In turn, Ywain becomes upset and angry and revenges the lion when the beast is injured by false assailants (151).

Ywain and Gawain also adds several interesting details; in this version, the lion seeks a method to commit suicide when he believes that Ywain has been killed. In fact, Ywain and the lion are so inseparable that when Ywain is reunited with his lady at the end of the romance, the lion also lives in joy and bliss with the couple until his death (ll. 4023-26). The lion stands in the place of Ywain's most trusted companion and servant, as Lunet is for Ywain's lady.

The notion of the lion as more natural than the dragon also appears in Chretién's

Perceval, in which

Perceval, like Yvain, encounters a lion and a dragon fighting each other and chooses to aid the lion as the "more natural" creature. (This adventure is also recounted in Malory's

Morte d'Arthur. When Perceval encounters the lion and the serpent fighting during his quest for the

Holy Grail, he sides with the lion as it is the “more naturall beste of the two” (2.912).) Perceval's similar encounter suggests that lions are noble in direct contrast to the unnaturalness of dragons.

Though lions sometimes mark an individual's nobility of character, they are not generally tame; often, they are clearly meant to be feared. In the

Alliterative Morte Arthure, Arthur dreams of lions licking their lips because they have been drinking the blood of Arthur's loyal knights (228). Later in the same work,

Gawain is compared to a lion in fierceness when he battles

Mordred (246). The comparison suggests Gawain's strength (and presumably anger) as well as the ferocity of lions themselves.

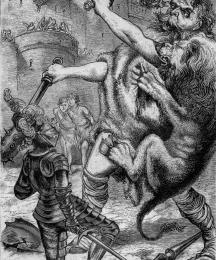

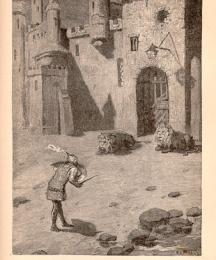

This is not the only time lions appear in relation to Gawain; he is attacked by a lion in Chretién's

Perceval. When Gawain stays one night in a fine castle, he sleeps in the Bed of Marvels, a fine bed that no man before Gawain has ever survived sleeping in overnight. In the middle of the night, a great bell sounds, and enchanted arrows fly through the windows, so that Gawain must jump off the bed. Just as he overcomes this trial, a churl lets in a monstrous lion, which attacks Gawain. Gawain eventually defeats the lion by cutting off its head and two paws (433).

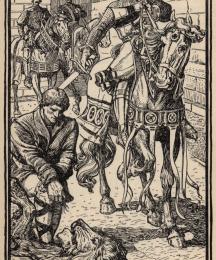

Lions threaten

Lancelot in another of Chretién's romances, but they are not frightening enough to deter him. In Chretién's

Knight of the Cart, two knights accompanying Lancelot think there are two lions waiting on the other side of the sword bridge he must cross to reach

Guinevere. They try to discourage him from crossing in part due to fear of these lions; Lancelot's decision to cross the sword bridge regardless reflects both his bravery and the strength of his love for Guinevere. After Lancelot successfully crosses the bridge, though, he discovers that there are no lions and that magic was at work (207-08).

Lions also feature in tests and miracles, particularly in the Lancelot-Grail cycle. In the Cycle's

History of the Holy Grail, a young Christian prince named Celidoine is set out to sea by his enemies in a small boat containing a lion. While his enemies presume that the lion will kill him, Celidoine's faith prevents him from being killed (1.95). The Cycle's

Lancelot recounts another test in which a young man must face lions and survive. It tells the story of Lanvalet, son of the missing King Eliezer, whose paternity is challenged. The boy is taken from his mother and put in a pit of lions, because lions will not attack the legitimate son of a king and queen. Of course, Lanvalet survives, and he is later reunited with his missing father (3.231). (This test is similar to the lions in the Middle English romance

Bevis of Hampton, who will not attack the princess Josian due to her noble birth.) These tests also seem to mimic Daniel's survival in the lion's den from the Biblical Book of Daniel, perhaps further emphasizing God's hand in both rescues. This emphasis would be particularly appropriate within the Vulgate Cycle, given its religious focus.

The Vulgate's emphasis on religion is also apparent in the appearance of a lion in the

Lancelot. In this part of the Vulgate Cycle, a knight retells the story of Joseph of Arimathea encountering a Saracen. When Joseph and his Saracen guide enter the city, a lion appears and kills the Saracen knight. Joseph is able to resurrect the dead knight and prove the power of God over the Saracen idols (3.89-90). The lion is thus a crucial element of God's plan, since its attack allows Joseph to convert Saracens.

Lions are powerful creatures throughout their appearances in medieval Arthuriana. While they are certainly dangerous foes, they often recognize and respond to nobility. The range of lions' appearances suggests that their significance depends more on the specific context in which they appear than on any one source of animal lore.

BibliographyFor more information about the version of works cited, see the Critical Bibliography for this project.

Read Less