Bedivere

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Welsh literature and the early chronicle tradition

- Twelfth and Thirteenth Century Romance

- Fourteenth-Century Romance and Malory

- Tennyson’s Idylls of the King

- Modern Fiction, Part 1: Bedivere as Storyteller

- Modern Fiction, Part 2: Bedivere in Non-Traditional Roles in “Historical” Novels

- Bedivere in Visual Art

- Film and Digital Media: Bedivere as a Comic Figure

Introduction

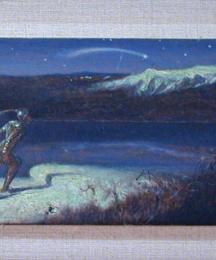

Sir Bedivere is best known to readers of the English Arthurian tradition as the knight charged with returning Excalibur to its lake of origin, as King Arthur lies mortally wounded from his final battle. Thrice Bedivere tries to follow his lord’s orders to throw the sword into the lake, but the first two times he is unable to part with Excalibur and keeps it as the last remaining symbol of Arthur’s glorious reign. He only musters the will to discard Excalibur on his third attempt, and is then rewarded with a marvelous sight: the Lady of the Lake’s hand rising from the water to catch the sword and draw it into the water, signaling the end of Arthur’s reign. Readers may associate Bedivere’s importance solely with this scene, but he in fact plays a larger role within the Arthurian tradition. Bedivere holds the curious distinction of bookending Arthur’s story: at the beginning of the tradition, he is named one of...

Read More

Read Less

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Welsh literature and the early chronicle tradition

- Twelfth and Thirteenth Century Romance

- Fourteenth-Century Romance and Malory

- Tennyson’s Idylls of the King

- Modern Fiction, Part 1: Bedivere as Storyteller

- Modern Fiction, Part 2: Bedivere in Non-Traditional Roles in “Historical” Novels

- Bedivere in Visual Art

- Film and Digital Media: Bedivere as a Comic Figure

Introduction

Sir Bedivere is best known to readers of the English Arthurian tradition as the knight charged with returning Excalibur to its lake of origin, as King Arthur lies mortally wounded from his final battle. Thrice Bedivere tries to follow his lord’s orders to throw the sword into the lake, but the first two times he is unable to part with Excalibur and keeps it as the last remaining symbol of Arthur’s glorious reign. He only musters the will to discard Excalibur on his third attempt, and is then rewarded with a marvelous sight: the Lady of the Lake’s hand rising from the water to catch the sword and draw it into the water, signaling the end of Arthur’s reign. Readers may associate Bedivere’s importance solely with this scene, but he in fact plays a larger role within the Arthurian tradition. Bedivere holds the curious distinction of bookending Arthur’s story: at the beginning of the tradition, he is named one of Arthur’s earliest and most loyal followers and, at the end of the story, he outlives his king. Bedivere’s presence at both the beginning and end of the narrative results from a melding of two separate traditions in the Arthurian canon—the chronicle tradition (which purports to be historical and focuses on Arthur’s military exploits) and the later romance tradition (which introduces more magical elements and valorizes courtly love). In the chronicle tradition, Bedivere is consistently named as one of the first knights dubbed by Arthur. He plays a prominent role in two episodes—Arthur’s fight against the giant of Mont Saint-Michel and the Roman campaign, where Bedivere dies gloriously in battle, fighting in his king’s mission to free Britain from Roman vassalage. Here, Bedivere is held up as an ideal knight—his courage, loyalty, and prowess are proven in his warrior’s death. In the romance tradition, on the other hand, Bedivere does not die in an early battle but survives to return Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake. Here, he serves as both the sole witness to Arthur’s passage to Avalon and as a messenger, bearing news of the king’s death to the surviving Round Table knights. When Sir Thomas Malory combined the two traditions—chronicle and romance—in his Morte d’Arthur, Bedivere became the only Round Table knight to live through Arthur’s entire reign—from his coronation through his death. A natural consequence is that in later retellings, Bedivere is frequently cast as the nostalgic narrator of Arthur’s story, Camelot’s sole survivor and a living memorial of the Arthurian golden age. Bedivere’s narrative role, then, shifts according to the literary trends of a given time period.

Raymond H. Thompson maps Bedivere’s historical development into five distinct stages (NAE 34). In this essay, I follow Thompson’s stages until the final phase, where I expand on his work. While Thompson limited his study of modern adaptations to novels, I include short stories, poems, films, web comics, and visual art, as well as a few texts written since Thompson’s 1991 publication. My survey of Bedivere’s historical development begins with early Welsh texts. According to Thompson, Bedivere enjoyed great popularity in the Welsh tradition, but later romance writers (especially in the thirteenth century) frequently downplayed or completely ignored Bedivere as a character; he never has his own eponymous romance and has very few adventures in comparison to more popular knights like Gawain, Lancelot, Tristan, and Perceval. Thompson reasons that this decline in Bedivere's importance parallels changing chivalric values: “Each new champion overshadowed his predecessor, not only defeating him in armed combat, but exposing the limitations of his standards of behavior” (Thompson 225).1 In the sections below, we see some of the knights who overshadow Bedivere in importance at various stages in his historical development. It is not until the twentieth century that Bedivere emerges out of the shadow of other knights and begins to play a major role in modern Arthurian fiction.

Welsh literature and the early chronicle tradition

Bedwyr, as he is known in the Welsh tradition, holds a position of prominence amongst Arthur’s warriors. He is the son of Pedrawd (Bruce 61) and father of two children, son Amhren and daughter Eneuog. Bedwyr’s name is sometimes accompanied by the epithet pedrydant, a term which can be broken down into two elements: petr(y) meaning ‘perfect, complete’ and dant meaning ‘sinew.’ Bedwyr is thus “perfect of sinew” (Bromwich 286), despite the fact that he is missing a hand (presumably from a war wound). This description emphasizes both his physical appearance and his skill in battle, two traits which explicitly characterize the Bedwyr in the Mabinogion’s tale of Culhwch and Olwen:

There was this about [Bedwyr]: none was so fair as he in this island except Arthur and Drych son of Cibddar. And this too: though he were one-handed, three armed men in the same field as he would not draw blood before him. Another gift of his was that his spear held one wound and nine counter-thrusts (Mabinogi 132).

The Mabinogi author’s emphasis on Bedwyr’s skill as a warrior is also consonant with his description in the Welsh triads, where he appears twice (in Triad 21 and 26 WR2). In the former, “Bedwyr son of Bedrawc” is singled out as the only man “diademed above” the “Three Diademed Battle-leaders of the Island of Britain” (41)—Drystan, Hueil, and Cai. While the significance of the diadems is unclear, Rachel Bromwich conjectures that they “appear…to have been a mark of distinction worn on the head by the foremost champions in battle, perhaps as an incentive to draw the enemy's attention to them” (41). The imposition of Bedwyr as a fourth individual in a genre which usually includes only three names suggests that Bedwyr is superlative in his courage. Indeed, this seems to be the sense in which his name is invoked by the fourteenth-century Welsh poet Iolo Goch in his panegyric to Edward III, whom he favorably compares to Bedwyr (Iolo Goch 2). Bedwyr is thus upheld as a paragon of warriors.

Also conventional in the Celtic corpus is Bedwyr’s close partnership with Cai (later Kay), though one scholar has called Bedivere “rather colorless compared to the admittedly controversial Kay” (Nickel 35). It is certainly the case that Welsh authors tended to give Cai greater prominence than his companion. The two are paired in almost all extant Welsh Arthurian literature: in both of Bedwyr’s appearances in the triads, in the earliest known Arthurian poem “Pa Gur yv y porthaur?” (“What Man is the Gatekeeper?”), in the Mabinogi, and in the eleventh-century Life of Saint Cadoc in which they team up to persuade an unusually lascivious Arthur not to “fulfill…his lustful desires upon a fleeing maiden” (Roberts 83). But Culhwch and Olwen portrays their partnership most extensively. In the tale, Cai’s and Bedwyr’s names are placed at the beginning of an enormous catalogue, a stunning list which names over 200 characters in Arthur’s court. Later in the tale, the pair share joint leadership over a group of seven warriors who undertake several quests together. In a memorable moment on one such quest, Bedwyr catches a poisoned spear thrown at him by a giant, and hurls it back to wound his enemy—a demonstration of his skill with spears mentioned in Triad 21. This is one of the few instances where Bedwyr takes center stage over Cai. But even though Cai is given a more active role in these adventures, it is Bedwyr who continues to serve Arthur after Cai abandons the quests (after Arthur insults him).

The Cai-Bedwyr partnership is further elaborated in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s twelfth-century chronicle, Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), where the two are usually identified as a pair and often act in parallel. Kay is named Arthur’s Seneschal in the same breath as Bedevere is his Cup-Bearer. After Arthur’s successful campaign in Gaul, he awards Kay lordship over Anjou, while Bedevere is simultaneously given Neustria (Normandy). To these minor mentions Geoffrey adds two Bedevere episodes that are not extant in the Celtic material. First, Bedevere and Kay acccompany Arthur in his battle against the giant of Mont Saint-Michel, a rare moment when Bedevere is featured over Kay. It is he who encounters a rape victim of the giant, and she chokes out her story to the sympathetic knight. Bedevere, deeply moved, comforts her with a promise of help and returns to Arthur with the news. After an enraged Arthur slays the giant, Bedevere is given the honor of decapitating the corpse and displaying it as a gruesome trophy. In the second of Geoffrey’s additions, Bedevere provides one of the chronicle’s most moving moments when he dies in the Battle of Saussy, impaled on the lance of Boccus, King of the Medes. His death spurs Kay into a vengeful fury and, in the process of retrieving Bedevere’s corpse, Kay himself receives a mortal wound. It is thus left to Hyrelgas, Bedevere’s nephew, to avenge his uncle:

[Hyrelgas] gathered round him three hundred of his own men, made a sudden cavalry charge and rushed through the enemy lines to the spot where he had sent the standard of the King of the Medes, for all the world like a wild boar through a pack of hounds, thinking little of what might happen to himself, if only he could avenge his uncle. When he came to the place where he had seen the King [Boccus], he killed him, carried off his dead body to his own lines, put it down beside the corpse of the Cup-bearer and hacked it completely to pieces. With a great bellow, Hyrelgas roused his fellow-countrymen’s battalions to fury exhorting them to charge at the enemy and to harass them with wave after wave of assault, for now a new-found rage boiled up within them and the hearts of their frightened opponents were sinking. (Geoffrey of Monmouth 252-53)

Bedevere’s death thus not only becomes an opportunity to enact familial vengeance but also serves as a turning point for the Britons in the larger battle. First Bedevere’s and then Kay’s deaths initiate a rallying of Arthur’s men, which ultimately leads to victory against the enemy. And in a final homage to their friendship, their twin burials are narrated in parallel with Kay buried in Chinon (in Anjou) and Bedevere in Bayeaux (in Neustria).

Twelfth and Thirteenth Century Romance

During the flowering of Arthurian romance in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, romance writers virtually ignored Bedivere as a character. He never stars in his own romance. If he is mentioned at all, it is only in a minor role or simply as a name at court. Chrètien de Troyes, arguably the creator of the Arthurian romance genre, scarcely brings up Bedivere in any of his five works. The voluminous Vulgate cycle, the most complete French iteration of the Arthurian story, mentions Bedivere only briefly and where he does appear, his adventures adhere closely to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s template. In these brief appearances, though, it is important to note a couple of key changes: first, he is consistently named as Arthur’s constable, rather than cup-bearer. According to A. J. Greimas’s Dictionnaire de l’ancien français, the earliest definition Old French conestable, which is roughly contemporaneous with these romances, stems from Latin comes stabuli, meaning head groom in a stable. Later, it signified authority more generally—as chief officer at court or field-marshal of an army. Thus, we begin to see Bedivere associated with the horses of Arthur’s cavalry, a detail that many modern writers will later appropriate. Second, though Bedivere sometimes fights in the Battle of Saussy, he survives it. He does not, however, go on to assume his iconic role quite yet. In the Vulgate cycle—the first time that Excalibur’s return to the lake occurs—the sword-thrower is identified not as Bedivere but as a knight named Girflet.3

Among the few romances that do give him original adventures—albeit in a cameo role—are the thirteenth-century Old French poem Yder, the Didot-Perceval, and Claris and Laris. His brief appearance in Yder shows a very different relationship between Bedoer and Kei. Instead of being Kei’s closest ally, Bedoer mocks Kei for his incompetence against the protagonist Yder (Kei is defeated thrice in jousting), warns him against dishonoring himself, and sarcastically shows more concern for the “finest Arab horse” (l. 1277; Romance of Yder pp. 68-69) that Kei rides than for the knight himself. The Didot-Perceval shows an even more scornful Beduier. In this text’s rendition of Arthur’s Roman campaign, Beduier and Gavain are sent to the Roman emperor with Arthur’s defiant message—a refusal to pay tribute to Rome. When one of the legates insults Britons, calling them liars and boasters, Beduier kills him on the spot, sparking a battle which ultimately leads to the British-Roman war. In both these romances, Bedivere is killed by Mordred’s forces when Arthur returns to Britain, following the general plotline of the chronicle tradition. In contrast, the Old French Claris and Laris casts Bedivere in a wholly original role as a mediator attempting to reconcile two feuding brothers, Alain and Davis. Bedivere is imprisoned in the attempt, and through Claris’ intervention, is eventually released. All of these Bedivere episodes, though, represent relatively brief incidents in romances largely designed to showcase the adventures of other knights.

Fourteenth-Century Romance and Malory

It is not until the mid-fourteenth-century English Stanzaic Morte Arthur that Bedivere survives both the Roman campaign and the final battle, and he replaces the Vulgate’s Girflet as the executor of the king’s dying wishes. The English poem is the first text to assign the task of returning Excalibur to the water to Bedivere. Here, we begin to see scenes familiar to modern readers. After the battle against Mordred, Bedivere and his brother Lucan carry the mortally-wounded Arthur to safety. Lucan literally works himself to death, causing his heart to burst, and leaves Bedivere alone with Arthur. It is at this point that the king commands Bedivere to cast Excalibur back into the sea. But Bedivere is unwilling to let the sword be lost to human hands, so he hides it and lies to Arthur that he has completed the task. Arthur sees through his deception and, after another failed attempt,4 Bedivere finally complies—throwing the sword back into the sea, where a hand rises out of the water to catch it and brandish it thrice before drawing it underwater. A century later, Malory’s adapted this scene in his Morte d’Arthur, emphasizing slightly different issues. For example, the reluctant Bedivere is twice lured into keeping the sword by its magnificent appearance: “And by the way he behylde that noble swerde, and the pomell and the hauffte was all precious stonys. And than he seyde to hymselff, ‘If I throw thys ryche swerde in the water, thereof shall never com good, but harme and losse’” (Malory 1239). Arthur, then, clearly attributes Bedivere’s disobedience to personal avarice, accusing his knight of desiring profit from Excalibur’s “ryches” (1239). Given that Excalibur symbolizes Arthur’s legitimate kingship, Bedivere’s behavior, Arthur insinuates, is tantamount to treason. The king even threatens to kill Bedivere should he fail for a third time to return the sword (1239). This scene, where Bedivere gains a defining role in Arthur’s death, is later immortalized by Tennyson.

Both the Stanzaic Morte and Malory continue to follow Bedivere after Arthur’s death. In the earlier poem, he joins a monastery where Lancelot eventually arrives after being rejected by Guinevere. There, Bedivere recounts the story of Arthur’s death to Lancelot and later witnesses Lancelot’s death. Malory expands these final scenes. As in the Stanzaic Morte, Bedivere is left alone after Arthur’s barge sails to Avalon and, distraught, he wanders in the forest overnight until he finds a hermitage. There, he discovers a newly-dug grave and hears the hermit’s story of the ladies in the night who came to bury an unnamed corpse. Bedivere identifies the grave as Arthur’s and renounces the knightly life for a holy one in order to fulfill his liege’s last request—to pray for his soul. Malory, however, famously questions Bedivere’s words: where Bedivere believes Arthur is definitely dead and buried, Malory introduces alternative, more hopeful, perspectives and leaves open the possibility that Arthur is still alive but grievously injured on Avalon. Malory implies that Arthur will return one day. In the end, when the seven surviving knights follow Lancelot’s dying wish to go crusading in the holy lands, Bedivere is the only knight to remain at Glastonbury, faithfully guarding the grave and praying for Arthur.

Other than his embellishments to this final scene in regard to Bedivere, Malory largely imitates the plotlines of his sources—either the fourteenth-century Alliterative Morte Arthure (an English poem in the same chronicle tradition as Geoffrey of Monmouth) or the Stanzaic Morte.5 Malory frequently calls Bedivere “the Bolde” or “the Rich [powerful],” two epithets which are attested in the English sources. He keeps Bedivere’s three key episodes: the fight against the giant of Mont Saint-Michel, the battle of Saussy, and the final return of Excalibur. Where Malory does take liberties, it is only in matters of emphasis. He downplays Bedivere and Kay’s friendship; unlike Geoffrey who has Kay rescue Bedivere in the battle of Saussy, Malory des not involve Kay in Bedivere’s wounding. It is instead Lancelot and Lovell who rescue Bedivere; Kay is injured separately. Such a change fits with Malory’s overall glorification of Lancelot as the ideal knight. If Malory’s Bedivere is partnered with anyone, it is not with Kay but with Bedivere’s brother, Lucan.

Tennyson’s Idylls of the King

Bedivere’s next evolution was to become not just a participant in the Arthurian story but also to narrate it, a step that first occurred in the Victorian era. Alfred Lord Tennyson, English poet laureate, was the first to explicitly feature Bedivere as storyteller in his Idylls of the King, capitalizing on the (insular, if not Continental) tradition of his presence both at the beginning of Arthur’s reign and at his death. Bedivere appears in only two of the Idylls, “The Coming of Arthur” and “The Passing of Arthur,” but both are important for bookending the narrative. His steadfast presence is acknowledged by Arthur, who commends him as the “[f]irst made and latest left of all the knights” (“Passing,” l. 2). Bedivere makes his first appearance in “The Coming of Arthur” when he is sent on the king’s behalf to Cameliard to sue for Guinevere’s hand in marriage. But when her father Leodegran questions Arthur’s legitimacy as king, the bold sir Bedivere—in an episode unique to Tennyson—lives up to his name by asserting himself: “[f]or bold in heart and act and word was he, / whenever slander breathed against the King” (“Coming,” ll. 175-76). The subsequent tale he tells to Leodegran is a version of Arthur’s origin story (one of several competing stories surrounding Arthur’s birth), reminiscent of Malory’s account. Though he did not witness Arthur’s birth, Bedivere asserts “[his] belief” that Arthur is the late king’s son, conceived out of wedlock by Uther and Ygerne, wife of Gorlois. After Uther’s death, Bedivere claims, Merlin whisked the infant prince away from the dangerous power vacuum surrounding the throne to the safety of Sir Anton’s household, where he was raised ignorant of his royal birth. Of the three narratives told of Arthur’s birth, Bedivere’s is the most realistic. Where the other storytellers, Bellicent and Bleys, give accounts that highlight the magical or divine elements of Arthur’s coming, Bedivere refuses to let mysticism color his report. (Even when Merlin appears, Bedivere does not call him a “mage” or even a “wise man,” as others do, but leaves his name unadorned.) Rather, Bedivere seems to believe that Arthur is simply and appreciably human; he situates his account between others’ who “call [Arthur] baseborn, and… hold him less than man, / And…those who deem him more than man, / And dream he dropt from heaven…” (“Coming,” ll. 179-82). The veracity of Bedivere’s account is open to debate, but Leodegran eventually consents to marry his daughter to Arthur, indicating his belief—concurring with Bedivere’s—that Arthur is a legitimate heir to the throne.

Bedivere’s role in the final idyll, “The Passing of Arthur,” puts readers in more familiar territory, adhering closely to Malory’s plot of Excalibur’s return to the Lake. One change that Tennyson makes is to intensify Arthur’s displeasure with Bedivere’s two failed attempts. After the first attempt, Arthur accuses him of disloyalty, betraying “thy fealty” (“Passing,” l. 243)—an insult that would no doubt sting the “first-made” knight. But when Bedivere fails for the second time, Arthur adds avarice and emasculation to his accusations: “Thou wouldst betray me for the precious hilt; / Either from lust of gold, or like a girl / Valuing the giddy pleasure of the eyes” (“Passing,” ll. 294-96). His insults hit home and Bedivere promptly executes Arthur’s orders in his next attempt.

More important than Arthur’s behavior is the access which Tennyson allows into Bedivere’s thoughts. Here, readers can see the discrepancy between Arthur’s accusations and Bedivere’s true, noble motives for keeping Excalibur despite his king’s orders:

“What record, or what relic of my lord

Should be to aftertime, but empty breath

And rumours of a doubt? But were this kept,

Stored in some treasure-house of mighty kings,

Some one might show it at a joust of arms,

Saying, ‘King Arthur's sword, Excalibur,

Wrought by the lonely maiden of the Lake….’

So might some old man speak in the aftertime

To all the people, winning reverence.

But now much honour and much fame were lost.” (“Passing,” ll. 266-77)

Here, Tennyson makes it clear that Bedivere’s intentions for the sword stem from his chivalric love for his king, rather than personal gain. His worries over others’ “doubt” have expanded from whether Arthur is a lawful king (in the first idyll) to whether he will be remembered at all. With Camelot razed to the ground, the vast majority of the Round Table knights dead, and no heir, Bedivere questions whether future Britons would believe that such an accomplished king and fellowship could ever have existed. To him, Excalibur is the one tangible artifact that might prove the truth behind the legend. The sword’s marvelous appearance, adorned with otherworldly “elfin” jewels, inscribed with “the oldest tongue of all this world,” and the blade “so bright / that men are blinded by it,” simply makes Arthur’s splendor that much more convincing (“Coming,” ll. 299-301). For Bedivere personally, the sword also seems like a relic of affective significance, the key to his own “treasure-house” of memories. It is Bedivere, not Arthur, who announces the end of a golden age. In a passage full of pathos, he laments that

“[N]ow I see the true old times are dead….

But now the whole Round Table is dissolved

Which was an image of the mighty world

And I, the last, go forth companionless,

And the days darken round me…” (“Passing,” ll. 397-405)

Bedivere’s final prayer is that “after healing of his grievous wound / [Arthur] comes again” (“Passing,” ll. 450-51). Thus, it is Bedivere who originates the idea of Arthur’s possible return. His wishful thinking seems to be rewarded as the final lines recount his hearing of “faint…sounds, as if some fair city were one voice / Around a king returning from his wars” (“Passing,” ll. 457-61). Tennyson’s final verses, however, are littered with qualifiers (“seems,” “he thought”) that allow skeptical readers to question Bedivere’s possibly biased perception. The seeds that Tennyson plants here are later sown and reaped by future writers who portray Bedivere as the primary narrator of Arthur’s story; some of them question Bedivere’s trustworthiness as an Arthurian chronicler and, like Tennyson, use his perspective as a means of complicating readers’ understanding of Arthur.

Modern Fiction, Part 1: Bedivere as Storyteller

Modern authors have appropriated Bedivere more often than one might expect; what writers seem to find attractive about Bedivere is that he provides an opportunity for them to reflect on the ethics of their craft. As the sole survivor of Camelot, Bedivere feels a responsibility to his lost king to tell and retell Arthur’s story in the hopes of keeping his memory alive. In telling Arthur’s story, Bedivere not only commemorates his lord but also is able to re-live the glory days of his youth when he played a crucial role in helping Arthur craft the golden age of his kingdom. As a result, twentieth and twenty-first century writers often cast Bedivere as both the firsthand source and the narrator of Arthur’s story, sometimes using an elderly Bedivere’s memories as the means by which we readers access the Arthurian narrative. By making Bedivere the narrator, these writers can claim to tell the “true,” behind-the-scenes story of the legendary king. Using Bedivere as a mouthpiece allows writers to pose questions like: How trustworthy a narrator is Bedivere? What kind of story is he telling? Should he be beholden to objective truth, reciting only those events he witnessed? Should readers allow Bedivere the leeway to glorify Arthur, even if this means exaggerating or downright ignoring the historical truth? Such questions raise issues regarding the ethics of storytelling and ultimately boil down to the vexed question of an author’s purpose in telling a story.

So-called “historical” novels are particularly apt to cast Bedivere as narrator because they, as a genre, are particularly concerned with historical realism or verisimilitude. Such novelists play with the idea of writers (even fiction writers) as historians, invested in chronicling or at least imagining a “real” world in which Arthur and his followers existed. They posit Arthur as a real figure and set his story in a particular historical moment, trying to render their narrative accounts as realistic as possible, building the Arthurian world out of Dark Age details and surrounding Arthur with historical and psuedo-historical figures. Some of these novelists include a preface or afterword which cites “facts” that “recent research” has unearthed about the historical Arthur. While the majority of historical novels I survey were published between the 1960s and 1980s, the historical fiction is still thriving in the twenty-first century. It should be noted that historical fiction is no longer confined to novels; some of the texts I examine explore similar themes of truth vs. fiction, but are not novels but rather short stories or even poetry. This section on modern literary interpretations of Bedivere is divided into two parts: first, I explore the trope of Bedivere-as-narrator in several texts; then, I look at Bedivere in major, but non-narrator, roles in other novels. I would like to point out that these two trends do not evolve in a linear manner from one to the other; rather, both occur simultaneously as authors explore various ways of making Bedivere a character more central to the Arthurian story.

Key ‘historical’ novels that feature Bedivere as narrator include George Finkel’s Twilight Province (1967; Watchfires to the North in the U.S.), Roy Turner’s King of the Lordless Country (1971), Catherine Christian’s The Sword and the Flame (1978; The Pendragon in the U.S.), and Wayne Wise’s Bedivere: The King’s Right Hand (2011). Christian’s novel is particularly interesting in its treatment of Bedivere. Narrated from his death bed in an abbey, Bedivere tells Arthur’s story to the monk Paulinus, who records it for posterity. As a scribe, Paulinus—like Christian herself—is invested in separating truth from legend; he pushes Bedivere for specific dates and statistics and, understandably, wants proof of Arthur’s Christianity. Christian’s choice of Bedivere as narrator allows her to play with the problematic concept of objective truth, especially in scenes where magic or mysticism is involved. For example, Bedivere hears of the Grail quest secondhand from Lancelot and does not hide his skepticism; he considers Lancelot mad for leaving Camelot undefended to go on a seemingly pointless search. Later, Bedivere twice witnesses a “red light” (Christian 494, 599) that he associates with the Grail, suggesting that Christian allows the possibility of a supernatural world to remain. But the ever-pragmatic Bedivere downplays these moments, preferring to help Arthur “man the fort” at Camelot while all the knights are Grail-questing.

At other key moments, Bedivere is absent; he misses the formative years of Arthur’s stint as “dux bellorum” or Count of Britain because General Ambrosius sends him to Byzantium as an ambassador to request military backing against the invading Saxons. Similarly, he forgoes participating in the Battle of Badon in favor of defending Camelot, and he is thus able to save Guinevere when the traitor Meliagaunt abducts her. At other times, Bedivere’s perception is compromised by illness or fever brought on by untreated battle wounds, making his memories vague. And Christian further complicates the reliability of his narrative by introducing other narrative voices. Although Bedivere witnesses Arthur’s drawing of the sword from the stone, readers hear about the event not as it happens but three years later and from two perspectives—first, through a boasting decurion who was on duty that day, and only later through Bedivere’s eyes. Bedivere, though, is less interested in the ceremony than in what follows it, a much more intimate scene where he witnesses Arthur falling in love and sleeping with his half-sister Ygern (Christian’s Morgause figure). Due to the personal and potentially controversial nature of this news, Bedivere withholds this information from Paulinus. He is a sensitive storyteller, omitting events from the official narrative that “a man concerned only with facts could never understand. The things that only Bards and the defeated know” (575).

To legitimate Bedivere’s narrative, Christian casts him in the role of a harper, the itinerant storyteller of the Middle Ages, who can sometimes be prophetic. Bedivere is chosen by the British natives to be trained as a harper and excels so far in his studies that he is named the new “Merlin” (a title, not a name) after Arthur’s death when the former bard can no longer perform his duties. As the Merlin, he has a duty to the people to keep alive their cultural heritage by telling and retelling Arthur’s story in the hopes that he might one day return. As one character tells Bedivere:

What you tell them, they will believe, and cherish, and their children after them. His memory, and the memory of the truths he lived by, are the heritage and the Hallows of Britain. They are all he had to leave. Only you, now, my dear, can see to it his people are not robbed of that rich heritage, for you are Merlin the Messenger. (589-90)

In keeping with this theme of music, Christian—instead of providing chapter titles—gives each section of her novel a musical notation (allegro, andante) or genre (aubade, march, requiem), allowing readers to imagine Bedivere performing the Arthurian story as a lay, with his harp in hand.

A lesser known but equally forceful portryal of Bedivere as narrator comes in Catherine Wells’ 2000 short story, “A Hermit’s Tale.” It would be more aptly titled “A Knight’s Tale” since the titlular hermit is revealed at the end to be the warrior Bedwyr, who—refusing to return to court after Arthur’s death—survives by “living like a hermit” off the land (Wells 18). But despite Wells’ chosen title, Bedwyr’s narrative style sounds like anything but a hermit’s; where readers might expect a secluded holy man to narrate tales in a subdued or moralistic tone, Bedwyr’s storytelling is fast-paced, gruff, engaging, and boldly opinionated. The tale reads like stream-of-consciousness, interrupted both by Bedwyr himself, who frequently pauses to address his listeners and demand more wine, and by his audience, who interjects comments. Reading Wells’ short story is an engaging experience, for readers are privy only to Bedwyr’s voice; even when Bedwyr’s listeners interrupt the tale, we do not hear them; instead, we hear only Bedwyr’s responses. Thus, based on clues in the text, we are asked to fill in the gaps, creating a participatory reading experience. For example, when Bedwyr pauses in his story to respond to a listener’s comment, he says, “Yes, yes, Gwenhwyfar, I haven’t forgotten” (13). From Bedwyr’s remark, readers learn that the queen is among Bedwyr’s audience; moreover, we might infer from earlier evidence that Bedwyr cares little about what others think of him, for he has recently called Gwenhwyfar a “silly nit of a thing” (11) despite the fact that she can hear his criticism.

Through such indirect evidence, Wells offers readers a unique characterization of Bedwyr. He is not only a colorful storyteller, but also a stereotypical knight. He cares little for affairs of heart, dismissing Gwenhwyfar and insulting her intelligence while praising Arthur for his clever strategems on the battlefield. Though he comes across as a somewhat boorish speaker, there are hints of a more courtly sense of honor. For instance, in the pivotal scene where Arthur requests he return the sword to the lake, Bedwyr—as in Malory—is tempted to keep the sword for himself, but eventually tosses it into the water because “I couldn’t think of a man worthy enough to hold it” (18). His knightly prowess emerges also in his open admiration for Arthur’s bloodlust and his own joy in battle. Bedwyr’s warrior spirit infuses the entire text; it comes to the forefront most prominently at the end, when he gives a definitive final interpretation of Arthur’s downfall:

Did [Gwenhwyfar] really think it was about her?

What?! Do I have to spell it out for you? It was about battle, you ninny! It was about a man who wasn’t really alive unless he was fighting someone! It was about a great lot of us who, when we had no Saxons left to fight, fought each other. Let me ask you something, boy. You must have heard the story of Camlann: who do they say won, Arthur or Medraut? Arthur? Well, that’s good. Tell it that way, that Arthur won the battle. But do you know who really won? The Saxons. The Saxons won, and they weren’t even there. Breton slew Breton, and in that one day we lost all the best warriors in the Isle of the Mighty.

We have defeated ourselves.

And what would Arthur say, do you suppose, if he knew what he’d done at Camlann?

Ha. He’d say, “But Bedwyr—wasn’t it a glorious fight?” (18-19)

Wells’ portrait of Bedwyr thus is unique not only for sketching a coarser portrait of Bedivere than Christian’s, but also for highlighting Bedwyr’s narrative role quite differently—asking readers to participate more actively in interpreting Arthur’s story through Bedwyr’s narration.

English poet Alan Brownjohn takes the trope of Bedivere as storyteller a step further, depicting him as a well-intentioned fabricator of fantastical tales. In his 1972 narrative poem, “Calypso for Sir Bedivere,” he reinterprets the final Excalibur scene to highlight the jarring discrepancy between a naïve, high-minded Bedivere and a grimly realistic world that cannot fulfill his expectations. Because it is told from Bedievere’s perspective, narrating in the first person his thoughts and speech, the poem’s style of sing-songy rhyming couplets lends its protagonist the air of youth and naiveté. We can see his idealism when Bedivere opens the poem by insisting on the importance of Excalibur: “But it was not only a sword to me. / It was a symbol, like, of virility” (Brownjohn 26). His earnest insistence that the sword means something causes him to question Arthur’s decision to discard it more openly than his earlier analogues, a pattern of thought that Brownjohn emphasizes by inserting a repeated four-line chorus with a fixed structure. The first two lines are always “Now King Arthur was a / Wise old king,” and the last two lines vary, though they always begin with a “but” to reveal ways in which Bedivere actually doubts Arthur’s supposed wisdom.

When Bedivere throws the sword into the lake, the results are disappointingly—though comically—pedestrian:

. . . . There was a clatter and I saw it drop

On the flat of its blade with an almighty plop,

Making little muddy bubbles in the foggy light

As it awkwardly, gradually sank from sight. (28)

Faced with such an anti-climax, Bedivere deliberately makes up a narrative to fit his fantasy, “a story, you will surely see, / Fit for a symbol of virility” (29). The product of Bedivere’s active imagination, we learn, is the marvellous version that Malory and Tennyson tell, where the Lady of the Lake’s samite-clad arm rises from the depths to catch the sword; and it is this tale that Bedivere tells to a skeptical, “gimlet”-eyed Arthur.

Then comes the unexpected twist, rendered in the chorus:

King Arthur was a

Wise old king

But he didn’t tell the truth

About everything. (29)

In the end, Arthur not only accepts Bedivere’s fictional account but also “revers[es] that history” to claim that “exactly the same thing happened to me. / And the way you describe you finally shot it, / That was the way I originally got it” (29). Like Bedivere, Arthur recognizes the allure of the sensationalized story, appropriates it, extends it to rewrite the origin story of the sword, and, in so doing, lends what is essentially a lie the authority of the king’s word. The implications of Brownjohn’s interpretation are far-reaching. Unlike Christian, who gets at the slippery nature of subjective truth, Brownjohn draws clear distinctions between truth and lies, but suggests that patently false tales can be disseminated as factual accounts when authorized by those in power. Moreover, the more such tales are repeated (as Brownjohn’s Arthur’s tale is retold by Malory and Tennyson), the more they assume the veneer of truth. Brownjohn, however, does not cast judgment on Bedivere for his deceptive words. Instead, he seems to accept that willful embellishment is simply the storyteller’s instinct. As he puts it, it is natural for “you” or, it is implied, any would-be narrator to tell “some fancy history / to make art cover up for reality” (30).

American fantasy writer Esther Freisner takes this idea of Bedivere as a fabricator to its logical, albeit extreme, conclusion, painting him as a malicious liar. In her 1996 short story, “Sparrow,” she shows the fall of Camelot from the point of view of a page pejoratively nicknamed Sparrow for his small stature and meek ways. Sparrow thanklessly serves a brutal and greedy Bedwyr, who has no qualms about stealing, lying, and killing for his own selfish ends. He routinely beats Sparrow and scavenges battlefields for the arms of dead knights (even his former comrades’) to sell for a profit. After the battle of Camlann, when he and Sparrow run across their mortally-wounded king, Bedwyr leads Arthur to a secluded spot in the forest away from prying eyes, on the pretext of bringing him to safety. There, Fresiner gives a horrific inversion of Bedivere’s final Excalibur scene: while Sparrow is sent to the Lake to collect water (where he encounters the mystical Lady of the Lake), Bedwyr uses the king’s own sword to execute Arthur and subsequently claims the throne. Aftewards, Bedwyr invents the tale audiences are most familiar with—where Arthur requests him to return the sword to the lake—but adds a twist ending: he claims that after he successfully threw the sword into the water, the Lady of the Lake brought it back to him and said:

“‘Arise, Sir Bedwyr! Arise and take what is yours by right. Shall this good blade rust beneath the waters while Britain stands in need? Shall this metal crumble away while there remains one fit to wield it?’ And she gave the sword to me [Bedwyr].” (Fresiner 240)

Like Brownjohn’s Bedivere, Freisner’s Bedwyr concocts fictions; but unlike Brownjohn’s knight, this Bedwyr manipulates the truth for his own selfish ends, to justify his usurpation of the throne. Moreover, he coerces the terrified Sparrow into verifying his false account, acting as the sole witness of that night’s events. Eventually, Bedwyr’s increasing abuse of power spurs the submissive and guilt-ridden Sparrow into defiant action, and he finally reveals the truth to the court. Although the story focuses more on the title character’s maturation, Freisner’s text is one of the most original portrayals of Bedivere, taking bold liberties in transforming his character into that of an evil knight. As far as I know, Freisner’s account is one of very few texts which depict Bedivere negatively.6 But Freisner’s heartless version of Bedivere draws on one of the anxieties present in the original texts, posing questions like: What is the role of the storyteller? Must he always tell the truth? Is truth always morally superior to fiction or fantasy? Can fictionalized stories serve political ends? At what point are lies justified? When viewed in light of such questions, Freisner’s conniving Bedwyr is arguably the flip side of Brownjohn’s idealistic one.

Modern Fiction, Part 2: Bedivere in Non-Traditional Roles in “Historical” Novels

While some novelists depict Bedivere as the last survivor of Camlann,7 others further expand Bedivere’s role. They feature him not as the narrator of the Arthurian story and last knight standing but in other key roles, sometimes replacing more popular Arthurian knights. In this stage of evolution, according to Thompson, Bedivere regains the position of prominence he occupied in the earliest Celtic texts, emerging out of the shadow of Kay and Lancelot in modern retellings. Among the authors who make him a substantial character (but not a narrator) are Parke Godwin in Firelord (1980), Rosemary Sutcliff in Sword at Sunset (1963), Gillian Bradshaw in In Winter’s Shadow (1982), and Mary Stewart in The Wicked Day (1984).8 In raising Bedivere to a position of importance, three of these novelists give him traits usually associated with Lancelot: French or Breton origins and an adulterous affair (suspected or actual) with the queen. Several of these authors justify their decision to replace Lancelot with Bedivere by citing his “historical authenticity” or early association with Arthur, suggesting that Lancelot is a later, and thus less authentic, French import. Mary Stewart calls Lancelot “purely fictional” (Last Enchantment 478) and even goes so far as to suggest that “in his relationship with Arthur [Bedivere] seems to be the original of Lancelot” (Hollow Hills 496). By this, she seems to mean that Bedivere’s key features—his courage, fierce loyalty to Arthur, and (in Stewart’s version) his courtesy—match characteristics commonly associated with Lancelot, thus making Bedivere a natural choice to play Guinevere’s lover in retellings concerned with historicity.

Rosemary Sutcliff, who is among the first authors to replace Lancelot with Bedivere, endows her Bedwyr with traits like horsemanship and musicality, characteristics especially important to the Celts. His horsemanship highlights his close relationship to Artos, since the driving force behind Artos’ military triumphs is his well-trained cavalry. Bedwyr plays a formative role in the establishment of the breeding herd as the only man who can ride the black stallion who becomes the foundation sire of Artos’ warhorses. This episode enables Artos’ first meeting with Bedwyr, who is initially presented as an itinerant horse trader:

He was a very young man…but lean and sinuous already as a wolfhound at the end of a hard season’s hunting; naked save for a kilt of lambskin strapped about his narrow waist, the wool showing at the edges and something that looked surprisingly like a harp bag was slung from a strap across his bare shoulder. But…the thing that I chiefly noticed was his face, for it seemed to have been put together somewhat casually from the opposite halves of two completely different faces, so that one side of his mouth was higher than the other, and his dark eyes looked out from under one gravelly brow and one that flared with the reckless jauntiness of a mongrel’s flying ear. It was an ugly-beautiful face and it warmed the heart to look at it. (Sutcliff 50)

His literal two-facedness foreshadows his betrayal of Artos and his affair with the queen. Indeed, when Medraut drops his first malicious hints of carnal attraction between the two, Artos momentarily sees in Bedwyr “the face of my enemy” (432). His skill with harp and voice gives Sutcliff’s otherwise introverted Bedwyr a means of connecting with his fellow warriors and a vehicle for memorializing Artos’ victorious battles. Ironically, this trait that makes Bedwyr so popular among Artos’ men also attracts Queen Guenhumara’s interest and sparks their love affair. He first plays his harp to comfort her after she has lost her first child to illness and, later, as she nurses Bedwyr after a serious injury. This latter scene is reminiscent of Tristan’s and Isolde’s (the other Arthurian adulterers) earliest encounters, in which the lovers establish a rapport based on their mutual love of music while she nurses him back to health. After the momentous revelation of their affair, Bedwyr returns to Artos to help him fight his final battle against Medraut. Unlike Malory’s Lancelot, Sutcliff’s Artos and Bedwyr reconcile and their friendship is able to survive the adultery which, in Malory, irreparably tears Camelot apart. Sutcliff’s rendering of the famous final scene, in which Artos requests Bedwyr to throw his sword into the lake, does not signify the return of Excalibur to its supernatural forger, but is symbolic of Arthur’s passing of kingship to Constantine.

In a very different retelling, Parke Godwin casts Bedivere as Arthur’s foster brother, placing him in a role most commonly occupied by Kay. Bedivere grows up with Arthur, fights in their earliest battles together, is the first to swear allegiance, and is given a position of military importance (here, as Arthur’s standard-bearer). But unlike the novelists discussed earlier who replace Lancelot with Bedivere, Godwin’s Bedivere is the only knight who stands firmly with Arthur in his accusations against Guenevere—an episode original to Godwin. In Firelord, Arthur is caught between two worlds—the “historical” Romano-British court and the nomadic tribes of Celtic natives called Prydn. He is kidnapped by the Prydn in his adolescence (causing the usually stoic Bedivere to shed tears because he thinks Arthur is dead); and, while he is in captivity, Arthur grows to love their simple lifestyle so much that he marries Morgana, one of the Prydn matriarchs. But he returns to his former life when he sees a horde of invading Saxons and reverts to his old military instincts. From there, he ascends to kingship, including a political marriage with Guenevere. Much later, when Guenevere’s affair with Lancelot is in full swing, Morgana returns, hoping to be reunited with her husband and to introduce him to their son Modred. Arthur, still in love with Morgana, agrees to a public welcome, despite Guenevere’s vehement protests. When Morgana unwittingly insults and humiliates Guenevere before the entire court, the queen orders Lancelot’s men to kill Morgana and her entire family. Unbeknownst to her, Arthur elects to spend the night with his first wife and is there when Lancelot’s men attack and kill Morgana. Luckily, he posted Bedivere as a guard (the only man he trusts with his secret) and manages to overcome the assailants. Stricken with grief over Morgana’s murder, Arthur with Bedivere’s help tortures the remaining attacker into revealing their master. At court, Bedivere acts as sole witness when Arthur brings murder charges against Guenevere; and it is Bedivere himself who arrests Lancelot.

Godwin’s Bedivere is also unique because he does not remain a bachelor. Unlike Arthur, he embraces his humble beginnings (as son of Gryffyn, Uther’s master of horse); he marries his cousin Myfanwy and has a daughter named Rhonda. His marriage distances him from his soldierly duties, and allows him “something of his own for once” (Godwin 197), a fact that Arthur notes nostalgically. Myfanwy and Rhonda mellow Bedivere’s hard exterior, so that “[t]he long, too-taut body relaxed and filled out, the eyes and mouth lost the hard vigilance learned on the Wall” (197), and this newfound tenderness enhances Bedivere’s aptitude as Arthur’s adviser. When Guenevere miscarries Arthur’s child, Bedivere draws from his experiences as a father to comfort both her and Arthur. In fact, he grows so close to the royal couple that Arthur’s dying wish is to entrust him to return the imperial sword not to some magical mere but to Guenevere, so that she can rule legitimately. Arthur’s final letter to Guenevere beseeches her to listen to Bedivere as an adviser. Thus, both Sutcliff and Godwin are examples of novelists who raise Bedivere to a position of central importance in their retellings, and allow him to take on roles previously assigned to other Arthurian knights.

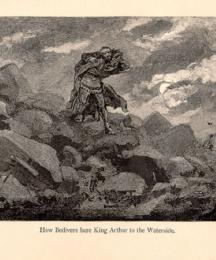

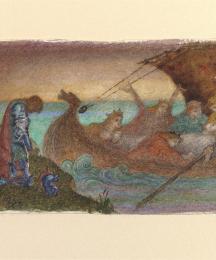

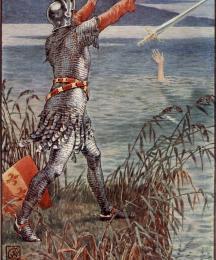

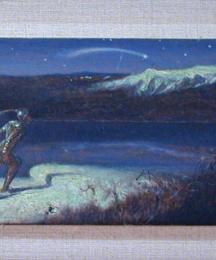

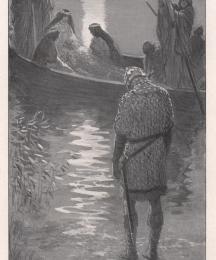

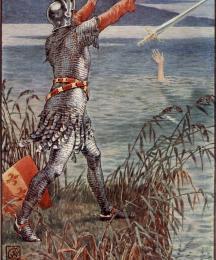

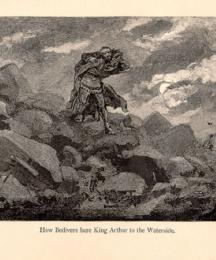

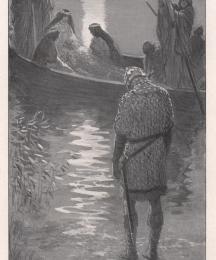

Bedivere in Visual Art

Bedivere is rarely represented in visual art. But when he does appear, artists (mostly painters) tend to portray his key moments in the “Death of Arthur” scene. As far as I can tell, there have been no noteworthy images of Bedivere’s earlier roles, either in the Celtic tales or in the chronicle tradition; surprisingly, I have found no renderings where he is featured in the battle with the giant of Mont Saint-Michel. Most paintings of Bedivere were composed during or after the pre-Raphaelite era in the nineteenth century. Children’s book illustrator Walter Crane and the Japanese-influenced Aubrey Beardsley are among those who have famously illustrated the scene where Bedivere flings Excalibur back into the lake. Other scenes commonly depicted include Bedivere watching over his wounded king on the battlefield (John Mulcaster Carrick, Sidney Harold Meteyard, and R. Scott Caple in a mixed media triptych) and Bedivere’s attempts to carry a mortally-wounded Arthur on his back to safety (Alfred Kappes and Frederic George Stephens). Artists who have portrayed a pensive Bedivere watching Arthur on the Avalon-bound barge include W. H. Margetson, Florence Harrison, Henry Hugh Armstead (in his bas relief in wood), William Hatherell, and Phoebe Anna Traquair.

Film and Digital Media: Bedivere as a Comic Figure

I would like to add a brief foray into recent Arthurian material that is not concerned with historicity but which has a more comic tone. Such material includes not only novels but film, graphic novels,9 and web comics that treat Arthurian characters with a tongue-in-cheek humor. In these texts, minor knights like Bedivere tend to be simply names indistinguishable from one another. But a few comic adaptations feature Bedivere more prominently, twisting source materials in innovative ways to surprise their audience. One thinks, for instance, of Terry Gilliam’s film Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) where Sir Bedevere is memorably introduced as a knight with an exceedingly strange brand of logic. His arrival coincides with a public accusation of witchcraft against a woman. Though Bedevere’s knightly appearance suggests that he might defend the woman or prove her innocence, Gilliam instead thwarts viewer expectations by having Bedevere reason his way to the opposite conclusion, using syllogistic logic. He observes that since both wood and witches burn, then witches must be made of wood. Furthermore, wood floats just like a duck, ergo if the woman weighs the same as a duck, she must be a witch. The comedic payoff comes not just in the fact that the woman and duck, when measured, unexpectedly balance the scales, but when Arthur, who has witnessed Bedevere’s sophistry, asks “Who are you who are so wise in the ways of science?” (Monty Python). Arthur proceeds to dub Bedevere the first knight of the Round Table not for his loyalty but for his demonstrated wisdom. Thompson calls such thwarted expectations “double reversals” (115), a technique Gilliam uses to deconstruct medieval stereotypes for ironic purposes.

With the inception of digital media, Bedivere’s character has become even more unstable. Paul Gadzikowski’s Arthur, King of Time and Space, a daily web comic, tells the familiar Arthurian story simultaneously in three separate timelines: the “fairy tale” or medieval Malorian arc, the contemporary arc, and the space arc. The contemporary arc casts the protagonists as adolescents in high school while the space arc, set in the future, locates them on the starship Excalibur. The juxtaposition of the three arcs allows Gadzikowski to set up the familiar medieval arc as something of a “control” group (in which all the characters inhabit their traditional roles), while changing key traits of certain characters in the other two arcs. Bedivere, for example, is paired with Kay as Arthur’s constant companions in the fairy tale arc but he is made female in the other two arcs (as are Tristram and Gareth), which allows Gadzikowski to reinterpret his partnership with Kay as a romantic one. As Christina Francis observes, this gender play “create[s] an interesting question….What qualities signify masculinity? Which femininity? Since his/her [personal] qualities never change, Gadzikowski’s strip argues for a conflation of gender determiners” (Francis 38). For example, “Bedivere” is accepted as a perfectly normal name for a woman, his physique is consistently slender, shorter than Kay’s, and blond-haired in all three arcs, and his female identity affects neither his professional rank (he and Kay share the post of deputy regent in the space arc) nor his knightly prowess (both he and Kay join ROTC in the contemporary arc). In almost all instances, he also dresses identically to Kay.

Gadzikowski also playfully acknowledges his debt to the earliest sources when Kay complains to Bedivere that

You and I were originally mainstays in Arthurian legends. Then Gawain got mixed in, and Lancelot got mixed in, and our roles were diminished. Now I only get remembered as a loudmouthed screwup, and you only get remembered if people read Tennyson in high school. (02/03/09)

Though readers may laugh, Gadzikowski’s knowledge of his sources allows him to alter the traditional plot in innovative ways. For example, Bedivere in the contemporary arc becomes the legal guardian of the orphaned Arthur and Kay because she turns 18 sooner than they do. Such a change could not have been made without implicit, Malorian assumptions that Arthur and Kay grew up as brothers and formed trusting relationships early in life, and that Bedivere was one of Arthur’s first and closest friends. In fact, Gadzikowski’s plot twist logically extends the relationship. Bedivere’s guardianship, according to Francis, makes her a maternal or “traditional childcare figure….or at the very least [a] responsible ‘adult’” (Francis 39) accountable for the antics of her younger step-siblings.

But in February 2009, Gadzikowski permanently reverted Bedivere’s sexual identity back to male in all the timelines. His rationale for doing so is narrated in an extended four-day dialogue between Kay and Bedivere, where they break the fourth wall to address readers directly. Having already explored a lesbian relationship with (female) Tristan and Isolde, Gadzikowski wanted now to depict a homosexual male relationship, though Bedivere wryly concedes this might be seen as “belated tokenism” (Gadzikowski 02/03/09). Meanwhile, a bewildered Kay asks “Do I get a say in this?” At the end of this arc, just as the ponytailed Bedivere transforms into a bearded one, Kay justifies Gadzikowski’s decision in knightly terms: “We were—and are—heroes, and heroes seek challenges. If being a happy gay couple in the face of possible charges of tokenism…is the quest to come our way, so be it.” (02/03/09)

The creation of the new homosexual couple proved timely. Two years later in December 2010, Gadzikowski cast both men in military roles in response to a contemporary controversy. In a strip published on Christmas Day 2010, Arthur asks Kay and Bedivere what they are doing for Christmas. The couple, both dressed in military camouflage, respond:

Bedivere: “Now that Don’t Ask Don’t Tell has been repealed—“

Kay: “—on New Year’s Eve we’re going across the state line and getting married.” (12/25/10)

Three years later, the story arc continues when the uniformed Kay introduces Bedivere (now visibly graying) as his husband. Gadzikowski draws Bedivere with only one arm, implying that he lost his other in battle. This detail functions on two levels, past and present: it shrewdly alludes to the Welsh tradition of the one-handed Bedwyr; and it allows for the decorated war hero Bedivere to qualify as legally “disabled,” though it is unclear if Bedivere reaps any financial benefits from his condition. In July 2013, Gadzikowski labeled Bedivere as transexual for the first time (07/13/13), which allowed one character to archly observe that “you couldn’t still be serving, because the US army classifies ‘Gender Identity Disorder’ as a disqualifying mental illness” (07/17/13). Gadzikowski’s changes to Bedivere’s traditional character clearly serve as political critiques, giving voice to marginalized populations (homosexuals, transexuals, veterans, the disabled) and allow Gadzikowski to engage with controversial current events. This latest evolution (or destabilization) of Bedivere, then, reminds us of just how adaptable the Arthurian story can be.

1. For example, Kay's brash behavior is superseded by Gawain's courtesy; later, Lancelot and Tristan surpass Gawain as courtly lovers; finally, the Grail knights, led by Perceval and Galahad, demonstrate Christian piety that contrast sharply with the lovers’ worldliness (Thompson 225).

2. Following Rachel Bromwich’s abbreviations in Trioedd Ynys Prydein, WR indicates the version of the Triads contained in the White Book of Rhydderch and the Red Book of Hergest.

3. Although Bedivere is typically identified as the sword-thrower in most adaptations, Alan Lupack points out a few versions where the role is assumed by another knight, “Girflet in the Vulgate Mort Artu; his squire in the Tavola Ritonda; Gawain, according to the fourteenth-century poem The Parlement of the Thre Ages; and Perceval in the film Excalibur (1981)” (Lupack 443).

4. A heretofore unremarked upon detail of the Stanzaic Morte Arthur’s rendition is that Bedivere tries to outsmart Arthur in a unique way the second time. Because Arthur knew Bedivere was lying the first time when he replies that he saw “nothing / But watres deep and wawes wan” (Benson and Foster ll. 3464-65), Bedivere decides to test if some marvel will happen by throwing only the scabbard into the lake: “’Yif any aventures shall betide, / Thereby shall I see tokenes good.’ / Into the se he let the scauberk glide; / A while on the land he there stood” (ll. 3472-75). Nothing of note happens, which Bedivere reports to Arthur, and Arthur knows that Bedivere has deceived him a second time.

5. Editor Eugène Vinaver points out that Malory’s Morte includes two knights whose names are coincidentally very similar to Bedivere’s, a Sir Pedy[v]ere and a Bedivere “of the Streyte Marchys.” The former appears in the Lancelot section of Vinaver’s edition and notoriously decapitates his unfaithful wife, despite Lancelot’s protests. The latter is defeated by Sir Bors in the Tristram section and is sent to Arthur to swear fealty to him. According to Vinaver, Caxton identifies this knight as “Pedyvere…in an attempt to identify him with a character in [the Lancelot section]. Pedyvere may well be a corruption of Bedyvere, but it is highly improbable that M[alory] himself saw any connexion between the two characters” (1525n800.17). I would add that neither of these characters seems synonymous with our Bedivere; certainly, none of the later Arthurian adaptations I have encountered attribute the actions of either Malory’s Pedyvere or Bedivere of the Streyte Marchys to the canonical Bedivere.

6. Edward A. Ryan also portrays Bedivere as a villain and traitor in his 2000 novel, The Last Knight of Camelot.

7. Among the prominent novelists who have rendered Bedivere the last living Arthurian knight are Mark Twain, Catherine Christian, Rosemary Sutcliff, Mary Stewart, Thomas Berger, and Stephen R. Lawhead.

8. The last two titles are individual novels in their respective trilogies.

9. One noteworthy comic novel to feature Bedivere as a character with a substantial, though very non-traditional, narrative arc is Tom Holt’s 2004 book, Grailblazers. Bedivere, nicknamed “Bedders,” is one of several knights-cum-pizza-delivery-boys who helps a time-traveling protagonist in his quest to achieve a grail-like object which will return him to his proper time.

Bromwich, Rachel, trans. Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain. 3rd ed. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2006.

Brownjohn, Alan. “Calypso for Sir Bedivere.” Warrior’s Career. London: Macmillan, 1972. Pp. 26-30.

Bruce, Christopher W. The Arthurian Name Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1999.

Christian, Catherine. The Pendragon. [British title: The Sword and the Flame] New York: Warner Books, 1978.

Francis, Christina. “Playing with Gender in Arthur, King of Time and Space.” Arthuriana 20:4 (Winter 2010), 31-47.

Freisner, Esther. “Sparrow.” Return to Avalon: A Celebration of Marion Zimmer Bradley. Ed. Jennifer Roberson. New York: DAW Books, 1996. 218-250.

Gadzikowski, Paul. Arthur, King of Time and Space. 2004-2014. <http://www.arthurkingoftimeandspace.com/>

Geoffrey of Monmouth. The History of the Kings of the Britain. Trans. Lewis Thorpe. Baltimore: Penguin, 1966.

Godwin, Parke. Firelord: The Glorious Epic Saga of King Arthur. New York: Doubleday and Co., 1985.

Iolo Goch. Poems. Trans. Dafydd Johnston. Llandysul: Gomer, 1993.

King Arthur's Death: The Middle English Stanzaic Morte Arthur and Alliterative Morte Arthure. Ed. Larry D. Benson and revised by Edward E. Foster. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1994.

Lacy, Norris J., and Geoffrey Ashe with Debra N. Mancoff. 2nd ed. The Arthurian Handbook. New York: Garland, 1997.

Lupack, Alan. The Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005.

The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales. Trans. and ed. Patrick Ford. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

Malory, Sir Thomas. The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. 3rd ed. Ed. Eugène Vinaver. Rev. by P. J. C. Field. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1990.

Mancoff, Debra N. The Arthurian Revival in Victorian Art. New York: Garland Publishing, 1990.

---. The Return of King Arthur: The Legend through Victorian Eyes. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1995.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Dir. Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones. Michael White Productions, 1975.

Nastali, Daniel P. and Phillip C. Boardman. The Arthurian Annals: The Tradition in English from 1250 to 2000. 2 vol. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004.

The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. 2nd ed., updated paperback edition. Ed. Norris J. Lacy, Geoffrey Ashe, Sandra Ness Ihle, Marianne E. Kalinke, and Raymond H. Thompson. New York: Garland, 1996.

Nickel, Helmut. “Surviving Camlann.” Quondam et Futurus 3.1 (Spring 1993): 32-37.

Poulson, Christine. “Arthurian Legend in Fine and Applied Art of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries: A Catalogue of Artists.” Arthurian Literature 9 (1989): 81-142.

---. “Arthurian Legend in Fine and Applied Art of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries: A Subject Index.” Arthurian Literature 10 (1990): 111-34.

Roberts, Brynley. "Culhwch ac Olwen, The Triads, Saints' Lives." The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature. Ed. Rachel Bromwich, A. G. H. Jarman, Brynley F. Roberts. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1991. Pp. 73-95.

The Romance of Yder. Trans. Alison Adams. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1983.

Simpson, Roger. “UPDATE: Arthurian Legend in Fine and Applied Art of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.” Arthurian Literature 11 (1992): 81-96.

Sims-Williams, Patrick. "The Early Welsh Arthurian Poems." The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature. Ed. Rachel Bromwich, A. G. H. Jarman, Brynley F. Roberts. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1991. Pp. 33-71.

Stewart, Mary. “Author’s Note.” The Hollow Hills. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1973. 491-98.

---. “Author’s Note.” The Last Enchantment. New York: Fawcett Crest, 1979. Pp. 476-80.

Sutcliff, Rosemary. Sword at Sunset. New York: Coward-McCann, 1963.

Tennyson, Alfred Lord. Idylls of the King. Ed. J. M. Gray. London: Penguin, 1983.

Thompson, Raymond H. “‘The Old Order Changeth…’: Bedivere in Arthurian Literature.” Moderne Artus-rezeption. Ed. Kurt Gamerschlag. Göppingen: Kümmerle, 1991. Pp. 225-36.

Wells, Catherine. “A Hermit’s Tale.” In The Doom of Camelot. Ed. James Lowder. Oakland, CA: Green Knight Publishing, 2000. Pp. 9-19.

West, G. D. An Index of Proper Names in French Arthurian Prose Romances. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1978.

---. An Index of Proper Names in French Arthurian Verse Romances 1150-1300. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969.

Read Less

by Geoffrey of Monmouth(Author), J. A. Giles (Editor)

by Lady Charlotte Elizabeth Guest (Translator), Anonymous (Author)

Images Gallery