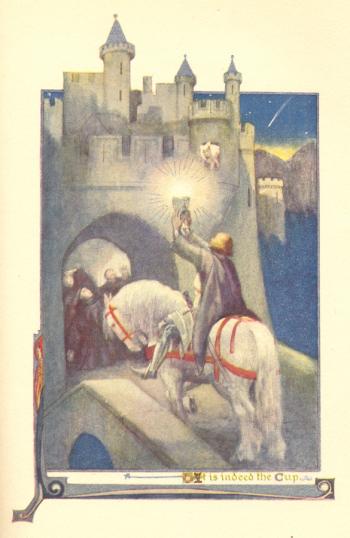

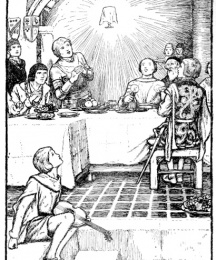

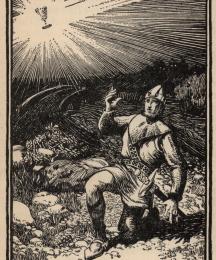

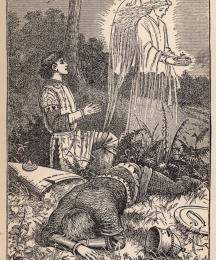

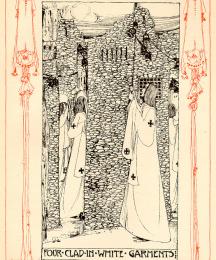

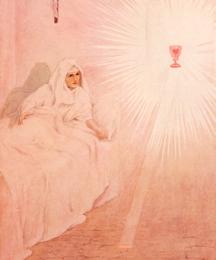

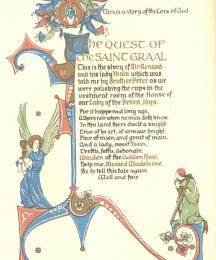

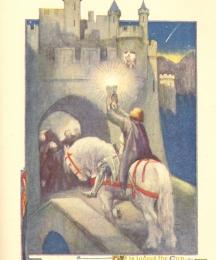

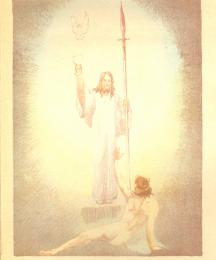

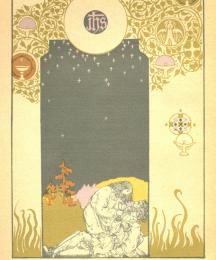

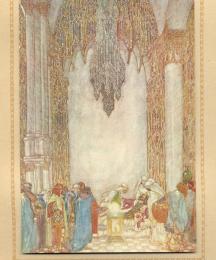

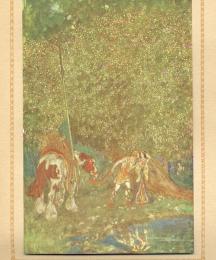

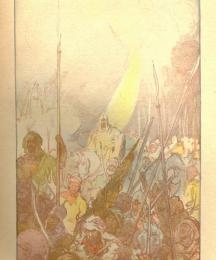

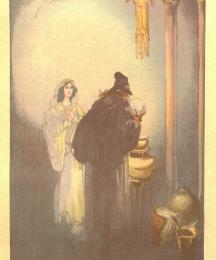

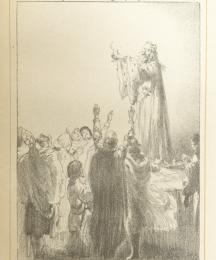

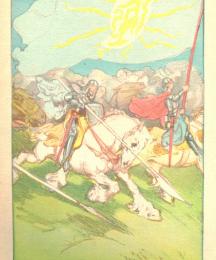

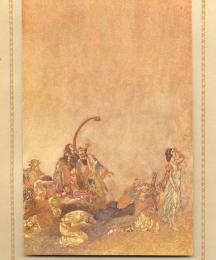

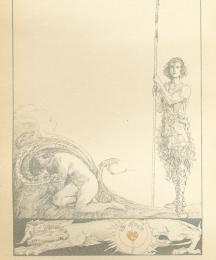

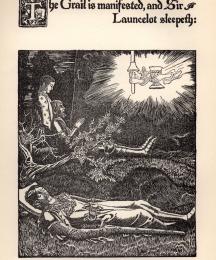

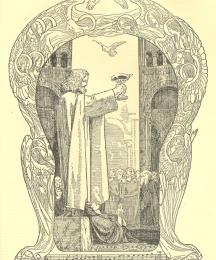

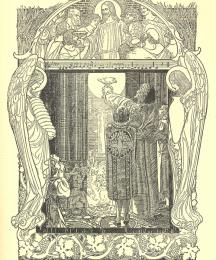

The Holy Grail is generally considered to be the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper and the one used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch his blood as he hung on the cross. This significance, however, was introduced into the Arthurian legends by Robert de Boron in his verse romance Joseph d'Arimathie (sometimes also called Le Roman de l'Estoire dou Graal), which was probably written in the last decade of the twelfth century or the first couple of years of the thirteenth. In earlier sources and in some later ones, the grail is something very different. The term "grail" comes from the Latin gradale, which meant a dish brought to the table during various stages (Latin "gradus") or courses of a meal. In Chrétien and other early writers, such a plate is intended by the term "grail." Chrétien, for example, speaks of "un graal," a grail or platter and thus not a unique item. Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival presents the grail as a stone which provides sustenance and prevents anyone who beholds it from dying within the week. In medieval romance, the grail was said to have been brought to Glastonbury in Britain by Joseph of Arimathea and his followers. In the time of Arthur, the quest for the Grail was the highest spiritual pursuit. For Chrétien, author of Perceval and his continuators (four works take up the task of completing the work that Chrétien left unfinished, two of which are anonymous, one is by Mannesier, and a fourth is by Gerbert de Montreuil), Perceval is the knight who must achieve the quest for the Grail. For other French authors, as for Malory, Galahad is the chief Grail knight, though others (Perceval and Bors in the Morte d'Arthur) do achieve the quest.

Tennyson is perhaps the author who has the greatest influence on the conception of

...

Read More

Read Less

The Holy Grail is generally considered to be the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper and the one used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch his blood as he hung on the cross. This significance, however, was introduced into the Arthurian legends by Robert de Boron in his verse romance Joseph d'Arimathie (sometimes also called Le Roman de l'Estoire dou Graal), which was probably written in the last decade of the twelfth century or the first couple of years of the thirteenth. In earlier sources and in some later ones, the grail is something very different. The term "grail" comes from the Latin gradale, which meant a dish brought to the table during various stages (Latin "gradus") or courses of a meal. In Chrétien and other early writers, such a plate is intended by the term "grail." Chrétien, for example, speaks of "un graal," a grail or platter and thus not a unique item. Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival presents the grail as a stone which provides sustenance and prevents anyone who beholds it from dying within the week. In medieval romance, the grail was said to have been brought to Glastonbury in Britain by Joseph of Arimathea and his followers. In the time of Arthur, the quest for the Grail was the highest spiritual pursuit. For Chrétien, author of Perceval and his continuators (four works take up the task of completing the work that Chrétien left unfinished, two of which are anonymous, one is by Mannesier, and a fourth is by Gerbert de Montreuil), Perceval is the knight who must achieve the quest for the Grail. For other French authors, as for Malory, Galahad is the chief Grail knight, though others (Perceval and Bors in the Morte d'Arthur) do achieve the quest.

Tennyson is perhaps the author who has the greatest influence on the conception of the Grail quest for the modern English-speaking world through his Idylls and his short poem "Sir Galahad". However, James Russell Lowell's "The Vision of Sir Launfal", one of the most popular of nineteenth-century American poems gave to generations a democratized notion of the Grail quest as something achievable by anyone who is truly charitable. The notion that the Grail story originated in fertility myths was popularized by Jessie Weston in her book From Ritual to Romance, which was used by T. S. Eliot in the writing of The Waste Land. Eliot's poem, in turn, influenced many of the important novelists of his and succeeding generations, including Hemingway and Fitzgerald.

The Quest for the Grail is treated in numerous films. Eric Rohmer's Perceval le Gallois is, for much of its plot close to Chrétien's romance. Monty Python and the Holy Grail blends motifs from medieval romance with outrageous humor. A number of films translate the medieval quest for the Grail into a modern setting. Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade involves a quest in which the title character finds then Grail realizes he cannot possess it but must "let it go." In The Fisher King, the modern quester, Jack Lucas, heals his friend Parry by achieving a cup that delusional Parry believes to be the Grail and, in the process, heals Parry and himself. A stop-motion film by Laura Lewis-Barr retells Percival's story in the modern world. Lewis-Barr's films rework fairy tales and mythic stories. In Percy Grows Up, she retells the story of Percival in a modern setting in which the commercial value of companies like Grail Industries is contrasted with the spiritual values of the true Grail. Despite its radically different form and setting, the film echoes the medieval tales of Percival's quest for the Grail.

BibliographyBarber, Richard W. The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Jung, Emma and Marie-Louise von Franz. The Grail Legend. Trans. Andrea Dykes. 2d ed.; Boston: Sigo Press, 1986. (Originally published in 1960 as Die Graalslegend in psychologischer Sicht.)

Loomis, Roger Sherman. The Grail: From Celtic Myth to Christian Symbol. New York: Columbia University Press, 1963.

Owen, D. D. R. The Evolution of the Grail Legend. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1968.

Waite, Arthur Edward. The Holy Grail: The Galahad Quest in the Arthurian Literature. New Hyde Park, NY: University Books, 1961.

Weston, Jessie L. The Quest of the Holy Grail. 1913; rpt. New York: Haskell House, 1965.

Read Less