Robbins Library Digital Projects Announcement: We are currently working on a large-scale migration of the Robbins Library Digital Projects to a new platform. This migration affects The Camelot Project, The Robin Hood Project, The Crusades Project, The Cinderella Bibliography, and Visualizing Chaucer.

While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

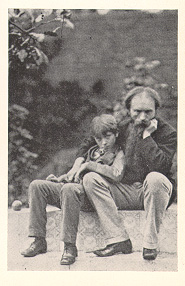

Edward Burne-Jones

Had he been able to, Edward Jones would not have chosen 28 AugustEdward Burne-Jones was an artist who by the late 1800's had revolutionized his profession by making the Pre-Raphaelite movement a mainstream event and using his artistic talents to create some of the most beautiful artwork that has ever come out of Britain. When he was just six days old, Burne-Jones' mother died due to complications of his birth. Consequently, his father saw him as being in some way responsible for the disaster and couldn't bring himself to touch his own child until Edward reached the age of four (Harrison and Waters, 1). Edward's relationship with his father was strained throughout his childhood to say the least, but his father did give him the gift of poetry at a very early age, exposure to which no doubt lead to an artistic career with strong literary ties. Burne-Jones remembered these earlier days in a letter to Mrs. Gaskell, "We had very, very few books, but they were poets all of them"(Harrison and Waters, 1). In 1844, Edward was placed in the King Edward's School, where his father initially enrolled him in a track to train in the field of commerce. By the time he turned fifteen, however, he was an extremely intelligent student with a wide range of literary interests, studying ancient and exotic cultures for his own enjoyment. At this time it was recommended that he be switched from the Commerce to the Classics program (Harrison and Waters, 4). The final step in Burne-Jones' formal education (and the beginning of his informal education) occurred at Oxford where he matriculated in June of 1852. There he was provided with a wealth of knowledge, but more importantly it was there where he met his lifelong friend, the poet William Morris (Harrison and Waters, 8).

1833 and the center of Birmingham as the time and place of his birth. He

would have preferred Florence of the fifteenth century with Botticelli as a

companion. (Harrison and Waters, 1)

With Morris, Burne-Jones spent endless hours in the library, finding and discussing poetry. As soon as they discovered how similar their interests were, they bonded and began a rather strenuous working relationship, pushing each other to absorb as much poetry as possible. It was through one of these sessions that Burne-Jones found what was to become his lifelong passion and source of inspiration, Malory's Morte d'Arthur. His first impressions of the poem can be seen in some of the journal entries he wrote while at Oxford. He comments on: "The depth, the mystery, the allegory—the beautiful characters of some of the knights" (Harrison and Waters, 11). Jones in fact became so enamored with the legends that he set out to create his own brotherhood in the reflection of Arthur's knights. A description of this group can be seen in a letter he wrote to his friend, Crom Price:

Remember, I have set my heart on founding a Brotherhood.The mission of this brotherhood was to "Crusade and [wage] holy warfare against the age . . . the heartless coldness of the times" (Harrison and Waters, 11). The group became a collection of artists and poets who became reverent readers of the myths and legends associated with Arthur and spent hours discussing the rites and ceremonies that take place in the stories. In 1857, their studying paid off as they were commissioned to decorate the Oxford Union Debating Hall with different scenes from the Morte d Arthur, which represent different virtues. The scenes that the artists painted are as follows:

Learn Sir Galahad by heart. He is to be the patron of our order.

I have enlisted one in the project up here heart and soul.

You shall have a copy of the cannons some day.

[signed] General of the Order of Sir Galahad (Harrison and Waters, 11)

J. Hungerford Pollen: King Arthur obtaining the sword Excalibur from the Damsel of the LakeBy 1855, the group had become quite sizable and they were working together to sell pieces that they produced. By 1861, the exhibitions of the group stopped and many artists went their separate ways, but while the Club lasted, it was invaluable to all of the artists, giving them a place to exchange ideas and to show their work to patrons (Harrison and Waters, 37). Arthur remained a strong influence on Burne-Jones after the group folded; and throughout the rest of his career, his work often returned to the myths that he first learned from Malory.

William Morris: Sir Palomides' jealousy of Sir Tristram

Val Prinsep: Sir Pelleas leaving the Lady Ettarde

Spencer Stanhope: Sir Gawaine meeting the three ladies at the well

Dante Rossetti: Sir Lancelot prevented by his sin from entering the Chapel of the San Graal

Arthur Huges: Arthur and the weeping Queens

Burne-Jones: Merlin imprisoned beneath a stone by they Damsel of the Lake (Harrison and Waters, 35)

His work on Henry Irving's production of J. Comyns Carr's King Arthur was something that revolutionized the way that the theater and the visual arts worked together. Burne-Jones actually knew Carr very well, as the Grosvenor Gallery (of which Carr was director) showed almost all of Burne-Jones' pieces. In fact, following his death, a large collection of Burne-Jones' art was displayed at the Grosvenor Gallery in an exhibit that focused on the entire body of work that Jones produced. Knowing Edward's strong interest in the Arthurian legends and his skill as a Pre-Raphaelite painter, Irving sought out Burne-Jones to design the sets and the costumes for his drama. Penelope Fitzgerald's biography recounts:

He accepted the commission because "weak moments comeThough he had an initial reluctance to join the production, once Arthur Sullivan agreed to do the music Burne-Jones was convinced and soon became very wrapped up in designing costumes and armor. He also drew sketches for the backdrops of the five main scenes—the Magic Mere, Camelot, the Maying of Queen Guinever, at the Chamber in the Turret, and the painting of Arthur's funeral Barge (Fitzgerald, 256). Burne-Jones describes the scenes in his sketchbook:

to me through friendship. I can't expect people to feel about the

subject as I do, and have always. It is such a sacred land to me." (Fitzgerald, 256)

1st prologue—Excalibur Arthur & Merlin coming down-a limitless meer, a high rock & path down which they come—rocks & rocks

1st scene—chamber in Arthur's court—closed interior—no outlook—Audience chamber & Guinevere bower—an upper chamber—a window at back through which Elaine can look down & see knights assembling to go on graal—principal feature is window which Elaine may throw open chamber by entrance on both sides

Last scene—great hall at Camelot—a broad high opening & knights riding by as in Laus Veneris—a big dais & throne—knights filing past while the king persuades Lancelot to stay—open air outside is essential—door on stage right—no door on left

Act 2—Queen's Maying

Act 3—Chamber above river—little chapel to left as you look at stage for her body. The rest of the stage is a heavy roofed loggia—with a parapet & view of the winding river. In the middle of the loggia are steps up which the knights come bearing the body

Act 4—Poison scene—with guarded window at back which changes to last scene of 1st Act. (cited in Harrison and Waters, 156).

The armour is good—they have taken pains with it—made in Paris & well understood—I wish we were not barbarians here. The dresses were well enough if the actors had known how to wear them—one scene I made very pretty—of the wood in Maytime—that has gone to nothing—fir trees which I had instead of beeches & birches which I love—why?—nevermind . . . . Merlin I designed carefully—they have set aside my designs and made him filthy & horrible—like a witch in Macbeth—from his voice I suspect him of being one of the witches—I do hate the stage, don't tell—but I do.Despite Burne-Jones' complaints, the production was largely successful both in Britain and in the United States. The critics also praised his work. In the Athenæum, the reviewer writes, "As a spectacle, nothing more beautiful and suggestive has been seen on the stage." He also speaks of: "the shadowy mystic beauty which appeals directly to the imagination and constitutes the very atmosphere of the legends" (Athenæum, 93).

(Harrison and Waters, 157)

Burne-Jones might have lost interest in Carr's play, but he never lost interest Arthur. In 1881, George Howard had commissioned an Arthurian piece from Burne-Jones to hang in his library at Naworth Castle. This piece, which eventually was entitled, Sleep of King Arthur in Avalon, was relinquished by Howard, as it became apparent that this would be the penultimate work of Burne-Jones' career. Burne-Jones never completely finished the work, dying before he could complete it. But the magnitude of it (it resides in the Museo de Arte, Ponce, Puerto Rico and couldn't be transferred to New York, due to its size, when The Metropolitan Museum of Art held a Burne-Jones exhibition) forever stands as a testament to Burne-Jones's accomplishments as a Pre-Raphaelite painter and to his undying commitment to recreate the Arthurian legend through images.

Bibliography

Casteras, Susan P., and Alicia Craig Faxon. Pre-Raphaelite Art in Its European Context. London: Associate University Presses, 1995.

"Drama: This Week." The Athenæum. 19 January 1895: 93.

Fitzgerald, Penelope. Edward Burne-Jones. London: Michael Joseph Ltd., 1975.

Goodman, Jennifer R. "The Last of Avalon: Henry Irving's King Arthur of 1895." Harvard Library Bulletin 32.3 (Summer 1984): 239-255.

Harrison, Martin, and Bill Waters. Burne-Jones. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1973.

Wildman, Stephen, and John Christian. Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian Artist-Dreamer. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998.