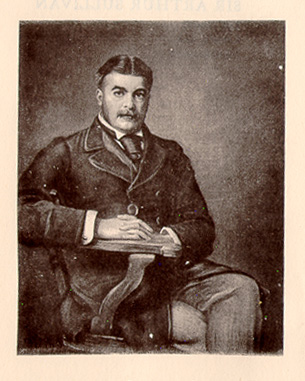

Sir Arthur Sullivan

On June 24, 1842, Arthur Sullivan was born in South London. He was christened with the middle name Seymour, though after realizing the potentially embarrassing monogram, he decided to revert back to the name on his birth certificate (which was simply Arthur Ssullivan)(Young, 4). Sullivan's father was a band conductor and recognized his young son's talent in music. Sullivan himself attributes his early introduction to music to his father:

The band my father conducted was small, but very good, for heThis strong interest led his parents to steer Sullivan into an educational path that would promote his interest. His training began at the Royal Academy of Music which he attended until 1858. He then moved on to Leipzig where he attended the Conservatory and produced one of his first respected works, The Light of the Harem (Ewen, 1). Over the next few years he expanded his classical pursuits and even earned money conducting; working for the Leeds Festival and the Royal Philharmonic until 1887 (Ewen, 2).

was an excellent musician. I was intensely interested in all that

the band did, and learned to play every wind instrument with which

I formed not merely a passing acquaintance, but a real, life-long,

intimate friendship. (quoted in Young, 5)

In 1871, Fred Clay (a singer who knew both of the musicians) introduced Sullivan to W. S. Gilbert, and began a partnership that would become one of the most successful duos in the history of musical theater. The first project the two of them worked on was a piece commissioned by John Hollingshed called, Thespis (Ewen, 3). Throughout their partnership they produced a huge body of work including such hits as: Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, Iolanthe, Princess Ida, The Mikado, Ruddigore, Yeomen of the Guard, and The Gondoliers. Though the team was popular, successful, and most importantly full of talent, social differences between the two musicians eventually got the best of their partnership. And a rather minor squabble that started over five hundred pounds worth of carpet ended in a separation announced in a rather short and curt note from Gilbert:

I am writing a letter to Carte . . . giving him notice that he is not to produce or perform any of my libretti after Christmas 1890. In point of fact, after the withdrawal of The Gondoliers, our united workIn July of 1894, Sullivan attempted to "escape his association with comic opera and do 'serious' music . .n . . He began composing a piece for King Arthur, commissioned by Henry Irving" (Dillard, 74). He had hoped for many years to write his own opera based on the Arthur legends, and saw a good opportunity to start this project by writing the incidental music for J. Comyns Carr's play. In his biography of Sullivan, Percy Young describes the composer's music for the play as follows:

will be heard in public no more. (Ewen, 4)

There is a "Grail" motiv which, used an ostinato, builds into a brief, effective chorus, tinged with grief as the voices-mostly in octaves--move from A flat towards G. major. The "May Song" is one of Sullivan's happiest inventions--a faux bourdon pattern for women's voices, floated above a tonic pedal with a fluttering background figure for the upper strings. (Young, 243)

(From "The May Song")

In the end, Sullivan was disappointed with the play when it took the stage in 1895. Burne-Jones, who was likewise disenchanted with the production, recalls Sullivan's attitude in one of his letters. Describing the final dress rehearsal, he writes: "Sullivan [was] in a fury-telling me he would've given 100 pounds to be out of it" (Goodman, 252).

In total, Sullivan composed the choruses of Lake Spirits, the Chaunt of the Grail, the May Song, a funeral march (a section of this march can be seen below), and the final chorus for Carr's play, and (according to Goodman) the King Arthur suite built upon these pieces is one of the best remaining testaments of this production (many of the remnants of which were lost in a warehouse fire). All in all, Sullivan's work on Irving's production was well received by most critics, but largely ignored by his biographers. Nevertheless, it was an important event as it brought together three knighted artists (Burne-Jones, Irving, and Sullivan) to create a collaborative project that was well received by audiences both domestically and abroad.

(From "The Funeral March")

1996.

Ewen, David. Sir Arthur Sullivan. Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, http://math.boisestate.edu/gas/html/ sullivan2.html. (Accessed on May 14, 2001).

Goodman, Jennifer R. "The Last of Avalon: Henry Irving's King Arthur of 1895." Harvard Library Bulletin 32.3 (Summer 1984): 239-255.

Young, Percy M. Sir Arthur Sullivan. New York: W. W. Norton, 1971.