Robbins Library Digital Projects Announcement: We are currently working on a large-scale migration of the Robbins Library Digital Projects to a new platform. This migration affects The Camelot Project, The Robin Hood Project, The Crusades Project, The Cinderella Bibliography, and Visualizing Chaucer.

While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

Pen and Pencil Sketches in Brittany

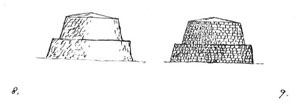

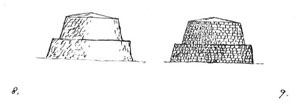

A SECOND lecture was given last night by Dr. Phené, before the Society for Encouragement of the Fine Arts, on the above subject. In the commencement he referred to his previous lecture, in which he pointed out that he had by rapid stages, traced sculpture in stone from the rude stone celt to the majestic sculptures of Greece and Rome, and that now, as he led his audience in imagination through the primitive and sylvan scenes of Brittany, he proposed to direct their attention to the sister art—the portrayal of nature by painting. Drawing some vivid word-pictures of the atmospheric changes and wonderful landscape tintings which had come under his notice in "the extensive forest scenes of the once magic wood of Broceliande," we extract the following out of a description of the rapid alternations of sunlight and shadow which he had witnessed:—"Occasionally, over the whole, coming winter cast its pinion. The sun went in, the shady retreat became chill, the verdant sapins looked dark and sombrous, the rich gold of the aspen leaves, and the bright metallic half-coppery half-tarnished golden hues of the woods of oak and other hard-wood trees became deeply stained with umber, and a few drops told of the storm slowly preparing by a mighty effort to remove the aged and worn-out, and the more loftily haughty denizens of the forest. Then, again, round patches of bright light moved in phantasmic pictures over hill and dale, stream and valley, green sapins and umbrageous oak woodlands; lighting up with necromantic touch the varied scenery, as though gods were using lorgnettes to view the earth, and the light of their own eyes shone through the tubes; and by it showing us, as they would see, things invisible before through the gloom; a sparkling château, set in an emerald lawn, a shining spire, and a distant village, a silvery line of river winding through the groves, now seen, now lost, as, like a serpent, it sought the great salt lake—all brought into beautiful but brief and spectral life, and again plunged in a darkness as of non-existence." Merlin's fountain, Osmundi ferns, six feet high and more, quaint villages, and rustic peasants filled up the intervals, till the travellers reached the princely château at Josselin, the palace of the Duc de Rohan. A verbal description of the architectural details of this interesting building was then given, accompanied by views of its imposing walls, which, built upon a lofty rock rising from the river's bank, has its rounded towers and structural defences much heightened by the scarping and cutting of' the sub-basement rock to the same outlines—so that the whole appears, till examined, a stupendous structure. The fantastic decorations of ogivale French architecture of the cour d'honneur—a decoration abounding in dragons and serpents, and found extensively throughout Brittany, exquisitely sculptured in the hardest granite, were made a prominent feature, the lecturer concluding, from these emblems being abundantly interwoven with the religious traditions of the country, as well Christian as Pagan, that the constant supremacy of the cross over them indicated a serpent theocracy, as the form of religion superseded by the Christian; the emblems being, he thought, too marked and multitudinous to be simply allegorical of evil or of a general Pagan faith, but that they illustrated the visible symbol of such Paganism. Not only are these forms found in some of the most ancient tomb chambers, but in deep subterranean crypts beneath the. churches, and always connected with some mysterious legend. Places, with other but similar mysterious legends, have their special and appropriate emblems—as the horses' heads sculptured in granite, bonded into and forming parts of the church tower at Penmarc'h, a very ancient name, meaning "horse's head." The embroidered dresses of the men in this district have been illustrated by Dr. Phené in the last number of the British Archæological Journal, and associated with the customs of an Oriental people. The exodus of the Huguenots from this  district on the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and the loss to France and gain to England from the ingenuity and industry of these refugees was pointed out. Going to the extreme south, the mouth of the Loire, the strange pagan customs till lately in full practice, were described, and the more utilitarian salt-procurers pictorially represented, with their picturesque costumes. One feature seemed of singular interest—the salt, when collected, is placed in large heaps, and covered with clay, till taken to the market. These heaps are principally made in lofty cones, and look like so many tents or wigwams, but the larger ones are in two stories, and formed in the exact shape and proportion of the nurhage of Sardinia, or the garden-houses which the lecturer had seen abundantly in Calabria and Otranto. All the natives here are admitted to be of foreign extraction, and ethnological ideas differ as to their origin. In the plate illustrating this lecture we give, side by side, a. figure of a "nurhag," and one of these larger salt mounds. Figs. 8 and 9.

district on the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and the loss to France and gain to England from the ingenuity and industry of these refugees was pointed out. Going to the extreme south, the mouth of the Loire, the strange pagan customs till lately in full practice, were described, and the more utilitarian salt-procurers pictorially represented, with their picturesque costumes. One feature seemed of singular interest—the salt, when collected, is placed in large heaps, and covered with clay, till taken to the market. These heaps are principally made in lofty cones, and look like so many tents or wigwams, but the larger ones are in two stories, and formed in the exact shape and proportion of the nurhage of Sardinia, or the garden-houses which the lecturer had seen abundantly in Calabria and Otranto. All the natives here are admitted to be of foreign extraction, and ethnological ideas differ as to their origin. In the plate illustrating this lecture we give, side by side, a. figure of a "nurhag," and one of these larger salt mounds. Figs. 8 and 9.

On the birth of landscape art, Dr. Phené said:—"The sister branch of art to which I referred at the outset—the pictorial representation of nature, as distinct from that of sculpture—struggled up with difficulty, and was almost choked by the thorns and briars of busy commerce and its money-seeking, on the one hand, and an unapproving ecclesiastical, and unappreciative unliterary and agricultural majority on the other. Taking us numerically, the English are, perhaps, the most reading people; while, artistically—judging from the products of its schools—England may be said to be the grand nation for landscape-painting; and for the representation of humble but true life, through painting, in the world. There must be some affinity, therefore, between literature and the fine arts. Thus, we find in its early days Art was only appreciated, only understood, by the great. Not because they were great, still less simply because they were wealthy, but because they were refined, because they were literary. When Art first sprang up the only literary communities were ecclesiastical—and, short of princes, they were the most able to encourage painters in a pecuniary sense. Hence, the great tendency of Art to ecclesiastical representation. But, growth once given, Art could not exist in servitude, and the arena of pictorial religion soon became too curtailed for it. Raphael, as I pointed out in my former lecture, was the first who opened the floodgates for a change from the curtailed church aspect. But, quite apart from such heresy, encouraged as it was by Leo X., in Italy, the great feature of Art in the German, Hanseatic, and Flemish schools, was an exhibition of total freedom as to subject. Rubens threw off all trammels with the drapery, but he dealt with the figure, which is not my subject. Van Goyen, Berchem, the Ruysdaels, drank in and gave out the sweets of Nature, yet the early paintings for the most part treated of the activity of man in goods-laden quays, or sailing craft, or of his more solid productions, as the Venetian palaces by Antonio Canal, or his Whitehall and Thames views. Cuyp basked on the sunny bank and chewed the cud of contemplation with his cattle; and old Crome showed us that a man could paint for love of his subject, probably without any other recompense. This was love of Nature, perhaps, more than of Art—i.e., a desire to portray that which they loved. Gainsborough had to leave his landscapes for the paying face-painting of his day; and Constable was not appreciated till our neighbours in France saw his excellence. Nor was Wilson valued. All these produced pictures for which abundant materials are still found in Brittany. The rural French are a non-reading people, the Bretons even far behind them, and we are taken back in their domestic life to the time when the English read only the Bible and the 'Vicar of Wakefield,' but worked vigorously like the Bretons of to-day. With our own reading our art-schools have progressed, till we drink the enjoyment of an Elysium in the rainbow poetry of a Turner; inhale, even in our London drawing-rooms, the fresh sea-breezes from a Hook, wander in imagination far over heathery hills with a Millais, punt it dreamily among sedge and water lilies, shaded from noontide heat, with a C. J. Lewis, or let the flecked skies of a Birket Foster hide from us the higher heaven that we may gaze on one below." The effect of poetry as antecedent to an age of free landscape-painting, was exemplified by Virgil's pastorals, which had, it was contended, influenced the pencil of Claude from his residence in Rome, and the intimacy, long established, between the sovereign houses of Lorraine and Italy, especially of Tuscany. In the same way, it was urged, Thomson heralded the present nature-painting by opening the public mind to its charms. The intense love of the Bretons for sweet pastoral scenery— the antecedent poetry of Armorica still influencing and inspiring their minds—warranted a rich harvest could the Breton mind be turned to free art, which, it was considered, could not be while the pall of semi-Pagan superstition still weighed down their intellects. A description followed of some of the midnight ceremonies, remains of Pagan rites, so ingrained into the people, that, as in some parts of the south of France the clergy, perhaps as a matter of policy, had formed them into Church festivals. A tumultuous orgie was generally held, which, when at its height, was suddenly hushed by a procession of priests and people chanting Latin hymns and carrying banners and emblems. Every person carried a torch or candle, the most brilliant and bizarre costumes added rich quaintness to the concourse, and a huge feu de joie lent its flickering light to heighten the dazzling scene. La danse ronde was always an accompaniment to the wild scene before the procession— a dance not unlike, till carried to extreme, to the round dances of Asia Minor at this day, at several of which Dr. Phené had been present, and a good representation of one was now to be seen in Mr. William Simpson's exhibition at Messrs. Colnaghi's, the drawing in question having been made by Mr. Simpson when he and Dr. Phené were present at the festival. This and very many other similarities between and Oriental customs were referred to.

On the mission of art, he said: "Art has its high mission, even in all its branches. The painter, the sculptor, the poet, the architect— he who carries away the soul on sweet sounds—he whose real office is to guide, to teach, and to admonish, whether by religious, moral, or legislative code, should see that all is holy, pure, and refined, and though it may be that among men posterity alone will know or acknowledge us, still let us work and labour in that atmosphere of sweetness which, like the fantasy of Turner's better paintings, is filled with spirit eyes and spirit whisperings that tell us that we are known and appreciated by them, though our crude clay covering keeps us from their actual embrace. No! When things seem out of harmony, let us again take a line from Ruskin treating of Turner, who says: 'When he was in his greater mind he saw that the world, however grave or sublime in some of its moods or passions, was nevertheless constructed entirely as it ought to be, and was a fair and noble world to live in and to draw in, and that when, as he sometimes seemed to think, the world was not quite all right, it was at those moments when he discovered, also, that all was not right within himself.' No! art is one of those pure and joyous outbursts of creature life and power which tell us that we are of that Creator whose works we scan, measure, ponder on, and delight in. And when we feel the

with spirit eyes and spirit whisperings that tell us that we are known and appreciated by them, though our crude clay covering keeps us from their actual embrace. No! When things seem out of harmony, let us again take a line from Ruskin treating of Turner, who says: 'When he was in his greater mind he saw that the world, however grave or sublime in some of its moods or passions, was nevertheless constructed entirely as it ought to be, and was a fair and noble world to live in and to draw in, and that when, as he sometimes seemed to think, the world was not quite all right, it was at those moments when he discovered, also, that all was not right within himself.' No! art is one of those pure and joyous outbursts of creature life and power which tell us that we are of that Creator whose works we scan, measure, ponder on, and delight in. And when we feel the  beautiful in nature's pictures, whether of the distant landscape or the towering mountain, the watery ripple, or the forest glade, we feel and know that we have a joy unfelt in former ages, and that some great hand has removed half the veil once resting dismally on man; when every chasm, grove, or mountain, every fount or exhalation was sacred to a demon or a to-be-propitiated deity, that some hand has opened a new life of liberty, and bids us behold the charms of earth, sea, and heaven, and rejoice. Nor bids in vain. We do see, love, and delight in such joys, when we repeat by art the forms, the colours, the mysterious and ever-varying tintings, free from the dread of a cruel power supposed to be ever lurking to destroy."

beautiful in nature's pictures, whether of the distant landscape or the towering mountain, the watery ripple, or the forest glade, we feel and know that we have a joy unfelt in former ages, and that some great hand has removed half the veil once resting dismally on man; when every chasm, grove, or mountain, every fount or exhalation was sacred to a demon or a to-be-propitiated deity, that some hand has opened a new life of liberty, and bids us behold the charms of earth, sea, and heaven, and rejoice. Nor bids in vain. We do see, love, and delight in such joys, when we repeat by art the forms, the colours, the mysterious and ever-varying tintings, free from the dread of a cruel power supposed to be ever lurking to destroy."

Other peculiar ceremonies and processions were then referred to, in which sometimes cattle, sometimes horses, take prominent parts among the religious dramatis personæ. The reception of the Countess at, and the description of, the fine but little-known Château of Brignac, and some interesting prehistoric remains in its neighbourhood, were then detailed. In the description of the people and their homes, the lecturer said: "Beyond the quaint picturesqueness of the external domestic architecture, which is a never-ending feast, there is little to describe of the homes or home manners of Brittany. The externals of the people are as rich, as varied, and as unaltered from old times, as are their residences, but internally there is the same monotony in each, and the people are reduced to mere machines. Any one homestead will give you all— any one real Breton man or woman will give you the nation. The people themselves can be described by two words— industry and faith. What a splendid foundation for mental freedom! Everything is unbelievably primitive. Even in the towns your Breton baker's bill is rendered on two pieces of notched stick, which fit together like the old tally of our Exchequer, the Welsh sticks of writing, or those Ezekiel was ordered to write on and join together into one."

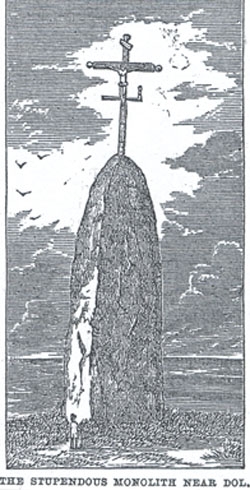

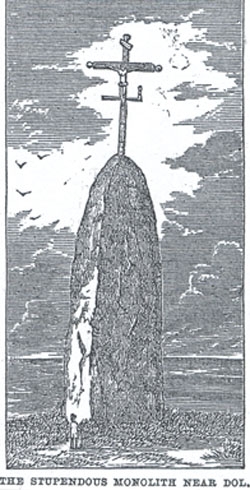

The grand prehistoric monuments—of one of which we give an example; viz., the stupendous monolith near Dol—were not much dwelt on, as an elaborate paper on this subject appeared from the pen of Dr. Phené, in the British Archæogical Journal in March last. The marvellous legends of the destruction, by inundation, of the Ville d'Is, and parallel legends in Wales, being also fully described in that journal, were only slightly recounted. This Breton legend, as well as that of the sand-buried town of Escoublac, showed evidently, it was pointed out, the strong tendency of the Bretton mind to superstition.

The grand discovery of Avalon was reserved for the last. This island, the reported burial-place of King Arthur, has been long lost sight of— so much so that Miss Betham Edwards, who went to find it, and with all her natural perseverance failed, comes to the conclusion that she would be right in concluding, with Mr. Baring Gould, that it belongs to one of the "class of myths referring to the Terrestrial Paradise, such as the Fortunate Isles of Pindar, the Garden of the Hesperides, &c." An extract from Miss Edward's glowing word-painting was then read. Her search and mental wonderings, as to which of the "amethestyne islands lying between a turquoise sky, and lapis lazuli sea," was the one in question. Following the same plan as that authoress, (i.e.) by local inquiry, and finding the same hopeless results, Dr. Phené

This island, the reported burial-place of King Arthur, has been long lost sight of— so much so that Miss Betham Edwards, who went to find it, and with all her natural perseverance failed, comes to the conclusion that she would be right in concluding, with Mr. Baring Gould, that it belongs to one of the "class of myths referring to the Terrestrial Paradise, such as the Fortunate Isles of Pindar, the Garden of the Hesperides, &c." An extract from Miss Edward's glowing word-painting was then read. Her search and mental wonderings, as to which of the "amethestyne islands lying between a turquoise sky, and lapis lazuli sea," was the one in question. Following the same plan as that authoress, (i.e.) by local inquiry, and finding the same hopeless results, Dr. Phené  determined to visit successively every island along the coast skirting the Arthurian district, and make special inquiries and search, as he had done for several successive years in the Morbihan sea. His attention was drawn to the careful geographical work of M. Ernest Desjardins, showing the changes and alterations of the coast line from its original boundary; but, as that work, while giving the coast to the east and west of the Arthurian district, omits that district in particular, Dr. Phené had to make his explorations by personally examining the geography and geology of the coast. Being guided in this way to a place off the bay of Lannion, where the sea has made great encroachments, and wandering over the different islands; the question was put for perhaps the five hundredth time— "Oú est l'Ile d'Aval?" when a fisherman quietly pointed to an adjacent island. This was considered too good—there might be some

determined to visit successively every island along the coast skirting the Arthurian district, and make special inquiries and search, as he had done for several successive years in the Morbihan sea. His attention was drawn to the careful geographical work of M. Ernest Desjardins, showing the changes and alterations of the coast line from its original boundary; but, as that work, while giving the coast to the east and west of the Arthurian district, omits that district in particular, Dr. Phené had to make his explorations by personally examining the geography and geology of the coast. Being guided in this way to a place off the bay of Lannion, where the sea has made great encroachments, and wandering over the different islands; the question was put for perhaps the five hundredth time— "Oú est l'Ile d'Aval?" when a fisherman quietly pointed to an adjacent island. This was considered too good—there might be some  mistake—another and another person was asked, with the same result. At last it was thought well to ask if the people knew the meaning of the word "Aval." The response was immediate "Aval—the Isle of Apples." The island was visited, but there were no trees. The occupants of the one small and solitary homestead persisted that it was "Aval, the Isle of Apples," and when asked how that could be, as there were no trees, pointed to the abundant orchards which clothed the shore of the mainland, and then at the inundations and encroachments of the sea as a sufficient answer. The mute reply was powerful, but close by was a much larger island, known by the name of the Grand Island. On this was found a dolmen unlike the usual examples in Great Britain or France, as it is distinguished by a grand peristalith which incloses a court round the structure,

mistake—another and another person was asked, with the same result. At last it was thought well to ask if the people knew the meaning of the word "Aval." The response was immediate "Aval—the Isle of Apples." The island was visited, but there were no trees. The occupants of the one small and solitary homestead persisted that it was "Aval, the Isle of Apples," and when asked how that could be, as there were no trees, pointed to the abundant orchards which clothed the shore of the mainland, and then at the inundations and encroachments of the sea as a sufficient answer. The mute reply was powerful, but close by was a much larger island, known by the name of the Grand Island. On this was found a dolmen unlike the usual examples in Great Britain or France, as it is distinguished by a grand peristalith which incloses a court round the structure,  and to that extent agrees with the surrounding lithic circle, within which were cut the deep rock tombs at Mycenæ, from which Dr.

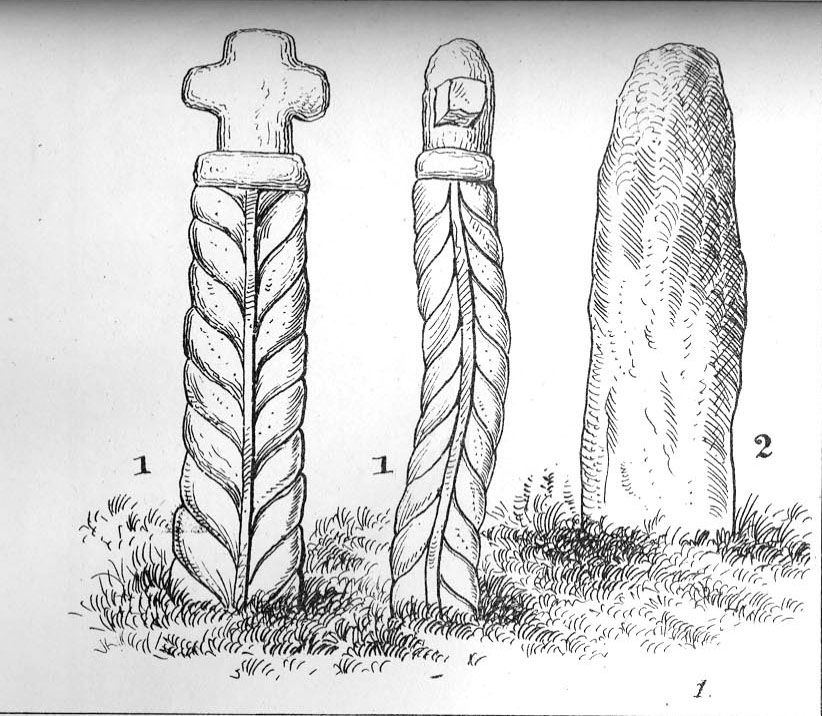

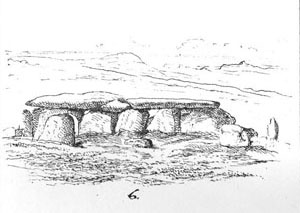

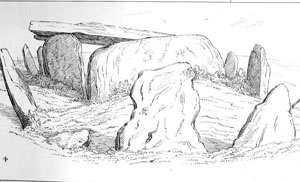

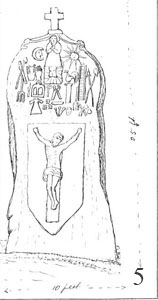

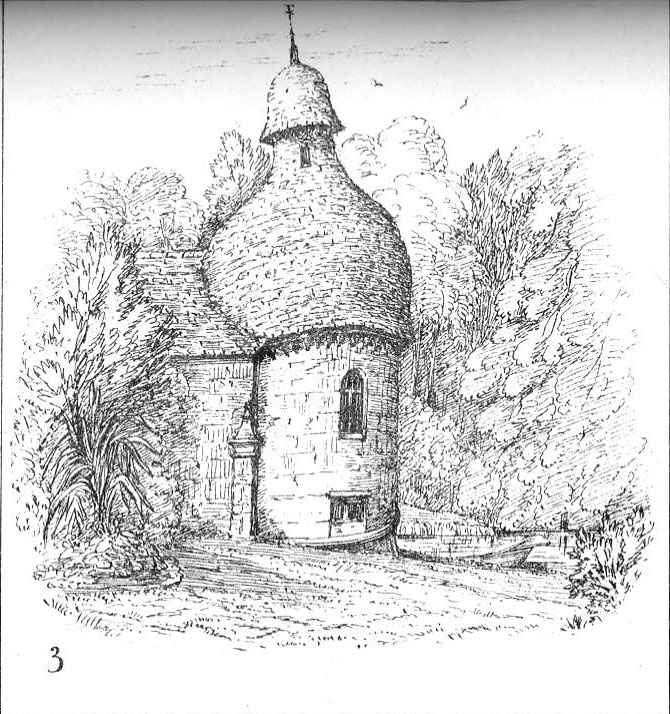

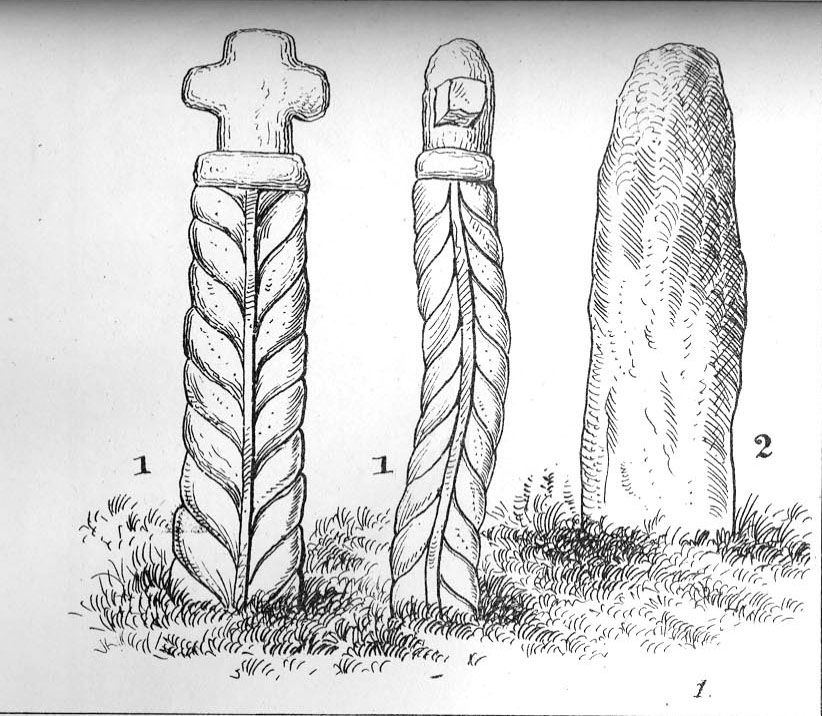

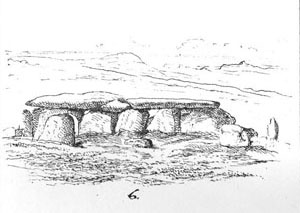

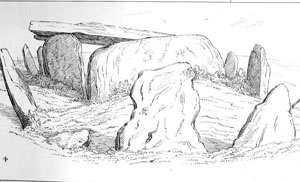

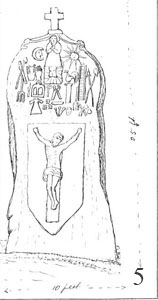

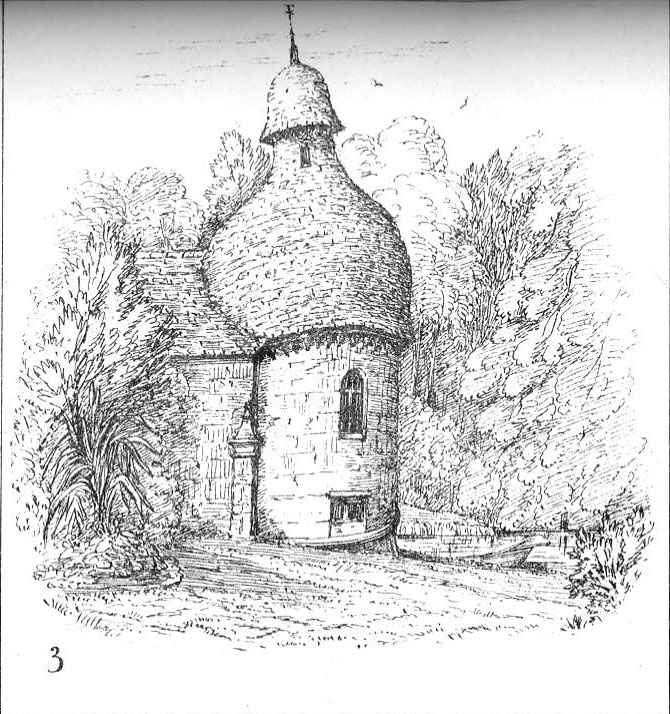

and to that extent agrees with the surrounding lithic circle, within which were cut the deep rock tombs at Mycenæ, from which Dr.  Schliemann has filled with treasure the museum at Athens. One of the chief reasons Dr. Phené had for visiting Mycenæ was to compare the Breton peristalith with that exhumed by Dr. Schliemann, his discovery of Aval having preceded Dr. Schliemann's report in the Times. A careful examination showed that Aval and this island had formerly been one, the one part only retaining the original name, and that consequently this grand tomb was once on the Isle of Avalon. In an old description of the coast this passage is found: "King Arthur was buried in the Isle of Aval or Avalon, lying off the coast of Lannion, not far off from his residence of Kerduel, or Karzuel, so famous in the legends of the Round Table." We give, among our lithographic plates, three views of this grand dolmen, with part of its inclosing circle, Nos. 4, 6, and 7; also a view of the old but still erect chapel of Kerduel, attached to the present château of the Marquis of Champagni (No. 3). This is the reported place of the birth of King Arthur, and its distance from the grand dolmen agrees with the above-quoted description. An enormous and quaintly-sculptured menhir commands a view of both islands (No.5). Two other great dolmens are found on promontories, one to the east, one the west, the three probably having originated the name of the present town of Tregastel (three castles), near which is found the menhir sculptured in the form of a serpent, bearing on its head a rude cross. Long disused and very ancient stone apparatus for cider-making was found on the island, with stone celts. The whole were purchased by Dr. Phené, as well as the estate on which the dolmen stands. The cider-making apparatus, which is identical with the old stone olive presses, long disused, but still to be found in the East, of which Dr. Phené found one on the Acropolis at Athens, and several in the Greek Islands (Cyclades), proves clearly that Avalon once had its apples.

Schliemann has filled with treasure the museum at Athens. One of the chief reasons Dr. Phené had for visiting Mycenæ was to compare the Breton peristalith with that exhumed by Dr. Schliemann, his discovery of Aval having preceded Dr. Schliemann's report in the Times. A careful examination showed that Aval and this island had formerly been one, the one part only retaining the original name, and that consequently this grand tomb was once on the Isle of Avalon. In an old description of the coast this passage is found: "King Arthur was buried in the Isle of Aval or Avalon, lying off the coast of Lannion, not far off from his residence of Kerduel, or Karzuel, so famous in the legends of the Round Table." We give, among our lithographic plates, three views of this grand dolmen, with part of its inclosing circle, Nos. 4, 6, and 7; also a view of the old but still erect chapel of Kerduel, attached to the present château of the Marquis of Champagni (No. 3). This is the reported place of the birth of King Arthur, and its distance from the grand dolmen agrees with the above-quoted description. An enormous and quaintly-sculptured menhir commands a view of both islands (No.5). Two other great dolmens are found on promontories, one to the east, one the west, the three probably having originated the name of the present town of Tregastel (three castles), near which is found the menhir sculptured in the form of a serpent, bearing on its head a rude cross. Long disused and very ancient stone apparatus for cider-making was found on the island, with stone celts. The whole were purchased by Dr. Phené, as well as the estate on which the dolmen stands. The cider-making apparatus, which is identical with the old stone olive presses, long disused, but still to be found in the East, of which Dr. Phené found one on the Acropolis at Athens, and several in the Greek Islands (Cyclades), proves clearly that Avalon once had its apples.

district on the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and the loss to France and gain to England from the ingenuity and industry of these refugees was pointed out. Going to the extreme south, the mouth of the Loire, the strange pagan customs till lately in full practice, were described, and the more utilitarian salt-procurers pictorially represented, with their picturesque costumes. One feature seemed of singular interest—the salt, when collected, is placed in large heaps, and covered with clay, till taken to the market. These heaps are principally made in lofty cones, and look like so many tents or wigwams, but the larger ones are in two stories, and formed in the exact shape and proportion of the nurhage of Sardinia, or the garden-houses which the lecturer had seen abundantly in Calabria and Otranto. All the natives here are admitted to be of foreign extraction, and ethnological ideas differ as to their origin. In the plate illustrating this lecture we give, side by side, a. figure of a "nurhag," and one of these larger salt mounds. Figs. 8 and 9.

district on the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and the loss to France and gain to England from the ingenuity and industry of these refugees was pointed out. Going to the extreme south, the mouth of the Loire, the strange pagan customs till lately in full practice, were described, and the more utilitarian salt-procurers pictorially represented, with their picturesque costumes. One feature seemed of singular interest—the salt, when collected, is placed in large heaps, and covered with clay, till taken to the market. These heaps are principally made in lofty cones, and look like so many tents or wigwams, but the larger ones are in two stories, and formed in the exact shape and proportion of the nurhage of Sardinia, or the garden-houses which the lecturer had seen abundantly in Calabria and Otranto. All the natives here are admitted to be of foreign extraction, and ethnological ideas differ as to their origin. In the plate illustrating this lecture we give, side by side, a. figure of a "nurhag," and one of these larger salt mounds. Figs. 8 and 9.On the birth of landscape art, Dr. Phené said:—"The sister branch of art to which I referred at the outset—the pictorial representation of nature, as distinct from that of sculpture—struggled up with difficulty, and was almost choked by the thorns and briars of busy commerce and its money-seeking, on the one hand, and an unapproving ecclesiastical, and unappreciative unliterary and agricultural majority on the other. Taking us numerically, the English are, perhaps, the most reading people; while, artistically—judging from the products of its schools—England may be said to be the grand nation for landscape-painting; and for the representation of humble but true life, through painting, in the world. There must be some affinity, therefore, between literature and the fine arts. Thus, we find in its early days Art was only appreciated, only understood, by the great. Not because they were great, still less simply because they were wealthy, but because they were refined, because they were literary. When Art first sprang up the only literary communities were ecclesiastical—and, short of princes, they were the most able to encourage painters in a pecuniary sense. Hence, the great tendency of Art to ecclesiastical representation. But, growth once given, Art could not exist in servitude, and the arena of pictorial religion soon became too curtailed for it. Raphael, as I pointed out in my former lecture, was the first who opened the floodgates for a change from the curtailed church aspect. But, quite apart from such heresy, encouraged as it was by Leo X., in Italy, the great feature of Art in the German, Hanseatic, and Flemish schools, was an exhibition of total freedom as to subject. Rubens threw off all trammels with the drapery, but he dealt with the figure, which is not my subject. Van Goyen, Berchem, the Ruysdaels, drank in and gave out the sweets of Nature, yet the early paintings for the most part treated of the activity of man in goods-laden quays, or sailing craft, or of his more solid productions, as the Venetian palaces by Antonio Canal, or his Whitehall and Thames views. Cuyp basked on the sunny bank and chewed the cud of contemplation with his cattle; and old Crome showed us that a man could paint for love of his subject, probably without any other recompense. This was love of Nature, perhaps, more than of Art—i.e., a desire to portray that which they loved. Gainsborough had to leave his landscapes for the paying face-painting of his day; and Constable was not appreciated till our neighbours in France saw his excellence. Nor was Wilson valued. All these produced pictures for which abundant materials are still found in Brittany. The rural French are a non-reading people, the Bretons even far behind them, and we are taken back in their domestic life to the time when the English read only the Bible and the 'Vicar of Wakefield,' but worked vigorously like the Bretons of to-day. With our own reading our art-schools have progressed, till we drink the enjoyment of an Elysium in the rainbow poetry of a Turner; inhale, even in our London drawing-rooms, the fresh sea-breezes from a Hook, wander in imagination far over heathery hills with a Millais, punt it dreamily among sedge and water lilies, shaded from noontide heat, with a C. J. Lewis, or let the flecked skies of a Birket Foster hide from us the higher heaven that we may gaze on one below." The effect of poetry as antecedent to an age of free landscape-painting, was exemplified by Virgil's pastorals, which had, it was contended, influenced the pencil of Claude from his residence in Rome, and the intimacy, long established, between the sovereign houses of Lorraine and Italy, especially of Tuscany. In the same way, it was urged, Thomson heralded the present nature-painting by opening the public mind to its charms. The intense love of the Bretons for sweet pastoral scenery— the antecedent poetry of Armorica still influencing and inspiring their minds—warranted a rich harvest could the Breton mind be turned to free art, which, it was considered, could not be while the pall of semi-Pagan superstition still weighed down their intellects. A description followed of some of the midnight ceremonies, remains of Pagan rites, so ingrained into the people, that, as in some parts of the south of France the clergy, perhaps as a matter of policy, had formed them into Church festivals. A tumultuous orgie was generally held, which, when at its height, was suddenly hushed by a procession of priests and people chanting Latin hymns and carrying banners and emblems. Every person carried a torch or candle, the most brilliant and bizarre costumes added rich quaintness to the concourse, and a huge feu de joie lent its flickering light to heighten the dazzling scene. La danse ronde was always an accompaniment to the wild scene before the procession— a dance not unlike, till carried to extreme, to the round dances of Asia Minor at this day, at several of which Dr. Phené had been present, and a good representation of one was now to be seen in Mr. William Simpson's exhibition at Messrs. Colnaghi's, the drawing in question having been made by Mr. Simpson when he and Dr. Phené were present at the festival. This and very many other similarities between and Oriental customs were referred to.

On the mission of art, he said: "Art has its high mission, even in all its branches. The painter, the sculptor, the poet, the architect— he who carries away the soul on sweet sounds—he whose real office is to guide, to teach, and to admonish, whether by religious, moral, or legislative code, should see that all is holy, pure, and refined, and though it may be that among men posterity alone will know or acknowledge us, still let us work and labour in that atmosphere of sweetness which, like the fantasy of Turner's better paintings, is filled

with spirit eyes and spirit whisperings that tell us that we are known and appreciated by them, though our crude clay covering keeps us from their actual embrace. No! When things seem out of harmony, let us again take a line from Ruskin treating of Turner, who says: 'When he was in his greater mind he saw that the world, however grave or sublime in some of its moods or passions, was nevertheless constructed entirely as it ought to be, and was a fair and noble world to live in and to draw in, and that when, as he sometimes seemed to think, the world was not quite all right, it was at those moments when he discovered, also, that all was not right within himself.' No! art is one of those pure and joyous outbursts of creature life and power which tell us that we are of that Creator whose works we scan, measure, ponder on, and delight in. And when we feel the

with spirit eyes and spirit whisperings that tell us that we are known and appreciated by them, though our crude clay covering keeps us from their actual embrace. No! When things seem out of harmony, let us again take a line from Ruskin treating of Turner, who says: 'When he was in his greater mind he saw that the world, however grave or sublime in some of its moods or passions, was nevertheless constructed entirely as it ought to be, and was a fair and noble world to live in and to draw in, and that when, as he sometimes seemed to think, the world was not quite all right, it was at those moments when he discovered, also, that all was not right within himself.' No! art is one of those pure and joyous outbursts of creature life and power which tell us that we are of that Creator whose works we scan, measure, ponder on, and delight in. And when we feel the  beautiful in nature's pictures, whether of the distant landscape or the towering mountain, the watery ripple, or the forest glade, we feel and know that we have a joy unfelt in former ages, and that some great hand has removed half the veil once resting dismally on man; when every chasm, grove, or mountain, every fount or exhalation was sacred to a demon or a to-be-propitiated deity, that some hand has opened a new life of liberty, and bids us behold the charms of earth, sea, and heaven, and rejoice. Nor bids in vain. We do see, love, and delight in such joys, when we repeat by art the forms, the colours, the mysterious and ever-varying tintings, free from the dread of a cruel power supposed to be ever lurking to destroy."

beautiful in nature's pictures, whether of the distant landscape or the towering mountain, the watery ripple, or the forest glade, we feel and know that we have a joy unfelt in former ages, and that some great hand has removed half the veil once resting dismally on man; when every chasm, grove, or mountain, every fount or exhalation was sacred to a demon or a to-be-propitiated deity, that some hand has opened a new life of liberty, and bids us behold the charms of earth, sea, and heaven, and rejoice. Nor bids in vain. We do see, love, and delight in such joys, when we repeat by art the forms, the colours, the mysterious and ever-varying tintings, free from the dread of a cruel power supposed to be ever lurking to destroy."Other peculiar ceremonies and processions were then referred to, in which sometimes cattle, sometimes horses, take prominent parts among the religious dramatis personæ. The reception of the Countess at, and the description of, the fine but little-known Château of Brignac, and some interesting prehistoric remains in its neighbourhood, were then detailed. In the description of the people and their homes, the lecturer said: "Beyond the quaint picturesqueness of the external domestic architecture, which is a never-ending feast, there is little to describe of the homes or home manners of Brittany. The externals of the people are as rich, as varied, and as unaltered from old times, as are their residences, but internally there is the same monotony in each, and the people are reduced to mere machines. Any one homestead will give you all— any one real Breton man or woman will give you the nation. The people themselves can be described by two words— industry and faith. What a splendid foundation for mental freedom! Everything is unbelievably primitive. Even in the towns your Breton baker's bill is rendered on two pieces of notched stick, which fit together like the old tally of our Exchequer, the Welsh sticks of writing, or those Ezekiel was ordered to write on and join together into one."

The grand prehistoric monuments—of one of which we give an example; viz., the stupendous monolith near Dol—were not much dwelt on, as an elaborate paper on this subject appeared from the pen of Dr. Phené, in the British Archæogical Journal in March last. The marvellous legends of the destruction, by inundation, of the Ville d'Is, and parallel legends in Wales, being also fully described in that journal, were only slightly recounted. This Breton legend, as well as that of the sand-buried town of Escoublac, showed evidently, it was pointed out, the strong tendency of the Bretton mind to superstition.

The grand discovery of Avalon was reserved for the last.

This island, the reported burial-place of King Arthur, has been long lost sight of— so much so that Miss Betham Edwards, who went to find it, and with all her natural perseverance failed, comes to the conclusion that she would be right in concluding, with Mr. Baring Gould, that it belongs to one of the "class of myths referring to the Terrestrial Paradise, such as the Fortunate Isles of Pindar, the Garden of the Hesperides, &c." An extract from Miss Edward's glowing word-painting was then read. Her search and mental wonderings, as to which of the "amethestyne islands lying between a turquoise sky, and lapis lazuli sea," was the one in question. Following the same plan as that authoress, (i.e.) by local inquiry, and finding the same hopeless results, Dr. Phené

This island, the reported burial-place of King Arthur, has been long lost sight of— so much so that Miss Betham Edwards, who went to find it, and with all her natural perseverance failed, comes to the conclusion that she would be right in concluding, with Mr. Baring Gould, that it belongs to one of the "class of myths referring to the Terrestrial Paradise, such as the Fortunate Isles of Pindar, the Garden of the Hesperides, &c." An extract from Miss Edward's glowing word-painting was then read. Her search and mental wonderings, as to which of the "amethestyne islands lying between a turquoise sky, and lapis lazuli sea," was the one in question. Following the same plan as that authoress, (i.e.) by local inquiry, and finding the same hopeless results, Dr. Phené  determined to visit successively every island along the coast skirting the Arthurian district, and make special inquiries and search, as he had done for several successive years in the Morbihan sea. His attention was drawn to the careful geographical work of M. Ernest Desjardins, showing the changes and alterations of the coast line from its original boundary; but, as that work, while giving the coast to the east and west of the Arthurian district, omits that district in particular, Dr. Phené had to make his explorations by personally examining the geography and geology of the coast. Being guided in this way to a place off the bay of Lannion, where the sea has made great encroachments, and wandering over the different islands; the question was put for perhaps the five hundredth time— "Oú est l'Ile d'Aval?" when a fisherman quietly pointed to an adjacent island. This was considered too good—there might be some

determined to visit successively every island along the coast skirting the Arthurian district, and make special inquiries and search, as he had done for several successive years in the Morbihan sea. His attention was drawn to the careful geographical work of M. Ernest Desjardins, showing the changes and alterations of the coast line from its original boundary; but, as that work, while giving the coast to the east and west of the Arthurian district, omits that district in particular, Dr. Phené had to make his explorations by personally examining the geography and geology of the coast. Being guided in this way to a place off the bay of Lannion, where the sea has made great encroachments, and wandering over the different islands; the question was put for perhaps the five hundredth time— "Oú est l'Ile d'Aval?" when a fisherman quietly pointed to an adjacent island. This was considered too good—there might be some  mistake—another and another person was asked, with the same result. At last it was thought well to ask if the people knew the meaning of the word "Aval." The response was immediate "Aval—the Isle of Apples." The island was visited, but there were no trees. The occupants of the one small and solitary homestead persisted that it was "Aval, the Isle of Apples," and when asked how that could be, as there were no trees, pointed to the abundant orchards which clothed the shore of the mainland, and then at the inundations and encroachments of the sea as a sufficient answer. The mute reply was powerful, but close by was a much larger island, known by the name of the Grand Island. On this was found a dolmen unlike the usual examples in Great Britain or France, as it is distinguished by a grand peristalith which incloses a court round the structure,

mistake—another and another person was asked, with the same result. At last it was thought well to ask if the people knew the meaning of the word "Aval." The response was immediate "Aval—the Isle of Apples." The island was visited, but there were no trees. The occupants of the one small and solitary homestead persisted that it was "Aval, the Isle of Apples," and when asked how that could be, as there were no trees, pointed to the abundant orchards which clothed the shore of the mainland, and then at the inundations and encroachments of the sea as a sufficient answer. The mute reply was powerful, but close by was a much larger island, known by the name of the Grand Island. On this was found a dolmen unlike the usual examples in Great Britain or France, as it is distinguished by a grand peristalith which incloses a court round the structure,  and to that extent agrees with the surrounding lithic circle, within which were cut the deep rock tombs at Mycenæ, from which Dr.

and to that extent agrees with the surrounding lithic circle, within which were cut the deep rock tombs at Mycenæ, from which Dr.  Schliemann has filled with treasure the museum at Athens. One of the chief reasons Dr. Phené had for visiting Mycenæ was to compare the Breton peristalith with that exhumed by Dr. Schliemann, his discovery of Aval having preceded Dr. Schliemann's report in the Times. A careful examination showed that Aval and this island had formerly been one, the one part only retaining the original name, and that consequently this grand tomb was once on the Isle of Avalon. In an old description of the coast this passage is found: "King Arthur was buried in the Isle of Aval or Avalon, lying off the coast of Lannion, not far off from his residence of Kerduel, or Karzuel, so famous in the legends of the Round Table." We give, among our lithographic plates, three views of this grand dolmen, with part of its inclosing circle, Nos. 4, 6, and 7; also a view of the old but still erect chapel of Kerduel, attached to the present château of the Marquis of Champagni (No. 3). This is the reported place of the birth of King Arthur, and its distance from the grand dolmen agrees with the above-quoted description. An enormous and quaintly-sculptured menhir commands a view of both islands (No.5). Two other great dolmens are found on promontories, one to the east, one the west, the three probably having originated the name of the present town of Tregastel (three castles), near which is found the menhir sculptured in the form of a serpent, bearing on its head a rude cross. Long disused and very ancient stone apparatus for cider-making was found on the island, with stone celts. The whole were purchased by Dr. Phené, as well as the estate on which the dolmen stands. The cider-making apparatus, which is identical with the old stone olive presses, long disused, but still to be found in the East, of which Dr. Phené found one on the Acropolis at Athens, and several in the Greek Islands (Cyclades), proves clearly that Avalon once had its apples.

Schliemann has filled with treasure the museum at Athens. One of the chief reasons Dr. Phené had for visiting Mycenæ was to compare the Breton peristalith with that exhumed by Dr. Schliemann, his discovery of Aval having preceded Dr. Schliemann's report in the Times. A careful examination showed that Aval and this island had formerly been one, the one part only retaining the original name, and that consequently this grand tomb was once on the Isle of Avalon. In an old description of the coast this passage is found: "King Arthur was buried in the Isle of Aval or Avalon, lying off the coast of Lannion, not far off from his residence of Kerduel, or Karzuel, so famous in the legends of the Round Table." We give, among our lithographic plates, three views of this grand dolmen, with part of its inclosing circle, Nos. 4, 6, and 7; also a view of the old but still erect chapel of Kerduel, attached to the present château of the Marquis of Champagni (No. 3). This is the reported place of the birth of King Arthur, and its distance from the grand dolmen agrees with the above-quoted description. An enormous and quaintly-sculptured menhir commands a view of both islands (No.5). Two other great dolmens are found on promontories, one to the east, one the west, the three probably having originated the name of the present town of Tregastel (three castles), near which is found the menhir sculptured in the form of a serpent, bearing on its head a rude cross. Long disused and very ancient stone apparatus for cider-making was found on the island, with stone celts. The whole were purchased by Dr. Phené, as well as the estate on which the dolmen stands. The cider-making apparatus, which is identical with the old stone olive presses, long disused, but still to be found in the East, of which Dr. Phené found one on the Acropolis at Athens, and several in the Greek Islands (Cyclades), proves clearly that Avalon once had its apples.

Additional Information:

In this electronic edition of "Pen and Pencil Sketches in Brittany," the editors have made two changes to the formatting of the article. First, the original text of this article appears without paragraph breaks. To increase the readability of the text, the editors have inserted paragraph divisions at appropriate points. In addition, the sketches associated with this article originally appeared in a separate section at the back of the journal. In the electronic edition, they have been inserted into the text.

In this electronic edition of "Pen and Pencil Sketches in Brittany," the editors have made two changes to the formatting of the article. First, the original text of this article appears without paragraph breaks. To increase the readability of the text, the editors have inserted paragraph divisions at appropriate points. In addition, the sketches associated with this article originally appeared in a separate section at the back of the journal. In the electronic edition, they have been inserted into the text.