Robbins Library Digital Projects Announcement: We are currently working on a large-scale migration of the Robbins Library Digital Projects to a new platform. This migration affects The Camelot Project, The Robin Hood Project, The Crusades Project, The Cinderella Bibliography, and Visualizing Chaucer.

While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

Pen and Pencil Sketches in Brittany

1 Lecture given before the Society for Encouragement of the Fine Arts, Conduit-street, Regent-street, by J. S. Phené, L.L.D., F.S.A., &c., 16th May 1878. The Rev. Thomas Wiltshire, M.A., F.L.S., F.G.S., &c., in the chair.

* In this electronic edition, the placement of some of the images has been altered. The sketches of the Cathedral and the Chateau of the Dukes of Rohan originally appeared in an index at the end of the volume.

2 Of Cologne.

3 Of Haarlem.

4 Of Dort.

5 Dryden's Life, of Virgil.

6 Dryden's translation of Virgil's forth Pastoral, line 30. Rather, perhaps the sweet epics of Syria. (Amomum)

7 Isaiah

8 Mr. Ruskin''s notes on Turner's drawings. Fine Art Society, 148, New Bond-st. 1878.

* In this electronic edition, the placement of some of the images has been altered. The sketches of the Cathedral and the Chateau of the Dukes of Rohan originally appeared in an index at the end of the volume.

2 Of Cologne.

3 Of Haarlem.

4 Of Dort.

5 Dryden's Life, of Virgil.

6 Dryden's translation of Virgil's forth Pastoral, line 30. Rather, perhaps the sweet epics of Syria. (Amomum)

7 Isaiah

8 Mr. Ruskin''s notes on Turner's drawings. Fine Art Society, 148, New Bond-st. 1878.

And in the wild woods of Broceliande,"

There stood "an oak so hollow huge and old,

It look'd a tower of ruin'd masonwork."— Vivien. Tennyson

On the occasion when I last read before your society I traced Art, by a few rapid stages, upwards, from the rude and imperfectly formed celt to the majestic sculptures of Greece and Rome, which, as I pointed out, embodied all but actual movement in the Godlike impersonations they were intended to represent, and terminated—as in a sort of afterthought— by a mere side glance at that which forms a characteristic, a sweet, loving, refining characteristic of our own age.

I propose now, as we travel together through Brittany, to take up the subject where I then left it, and have introduced that which gladdens the eye by the sister art which delights the ear; while both wake the healthy blood to a more rapid and warmer movement, but in the cup of pure sobriety; and tell of the delicious nectar of heavy dew, which weighs down the long ripe grass of the May morning of youth, and the purling of streams and fountains which ripple their silver music to the overheated wayfarer as he toils through the sultry dusty June of life. Nor omitting the primrose and violet, which little fays, such as we were once, still gather—the light laugh, and the large rich lustrous tear of childhood, which, when shed, as it often is, in sudden sympathy, or even bursting joy, bears aloft an incense more precious than the bright glistening sparkle of the smile which heralds the silver ring of laughter.

Such was the face of nature on a summer's day in mid autumn, in the extensive forest scenes of the once magic wood of Broceliande; when, with the fitful fantasy in which nature sometimes clothes herself, it might be spring, summer, or autumn, at your will. Warm enough for June, in the sunshine, a shady shelter beneath the interlaced boughs of beech and oak, brought the cool wind of autumn tempered with the warm breathings we sometimes feel, as coming summer kisses us in spring; the bright green of the sapins, which the eye could select in large or small patches, at choice, gave spring in all its verdure; and a wilful turn would plunge all in autumn, as, facing about, the broad oak woods, in their dark russet, were spread before us, so vast, that they melted away in the indefinable indigo tints, which often margin our own extensive views in Kent and Surrey.

Occasionally, over the whole, coming winter cast his pinion. The sun went in, the shady retreat grew chill, the verdant sapins looked dark and sombrous, the rich gold of the aspen leaves, and the bright metallic, half coppery, half tarnished golden hues of the woods of oak, and other hard wood trees, became deeply stained with umber, and a few drops told of the storm slowly preparing by a mighty effort, to remove the aged and worn out, and the more loftily haughty denizens of the forest.

And then round patches of bright light moved in phantasmic pictures, over hill and dale, stream and valley, green sapins and umbrageous oak woodlands, lighting up with necromantic touch the varied scenery, as though gods were using lorgnettes to view the earth, and the light of their own eyes shone through the tubes, and by it showing us, as they would see, things invisible before through the gloom; a sparkling château set in an emerald lawn, a shining spire, and a distant village, a silvery line of river winding through the groves, now seen, now lost, as, like a serpent, it sought the great salt lake; all brought into beautiful but brief and spectral life, and again plunged in the darkness of non-existence. Then the black canopy screening heaven would roll up for a time, and spring and summer beam once more upon us.

You will, I think, agree that the pen alone could here attempt to illustrate changes which the pencil of even a wizard could not achieve, though he were a very Merlin, nor even attempt, except by a whole series of paintings.

We drank, of course, of Merlin's fountain, the very water with which he is said to have wrought his spells; and willingly lost ourselves in the tangled nut-bearing brushwood, and Osmundi ferns six feet high and more; then through quaint villages, and once again reached the highway, le grand chemin, to a town.

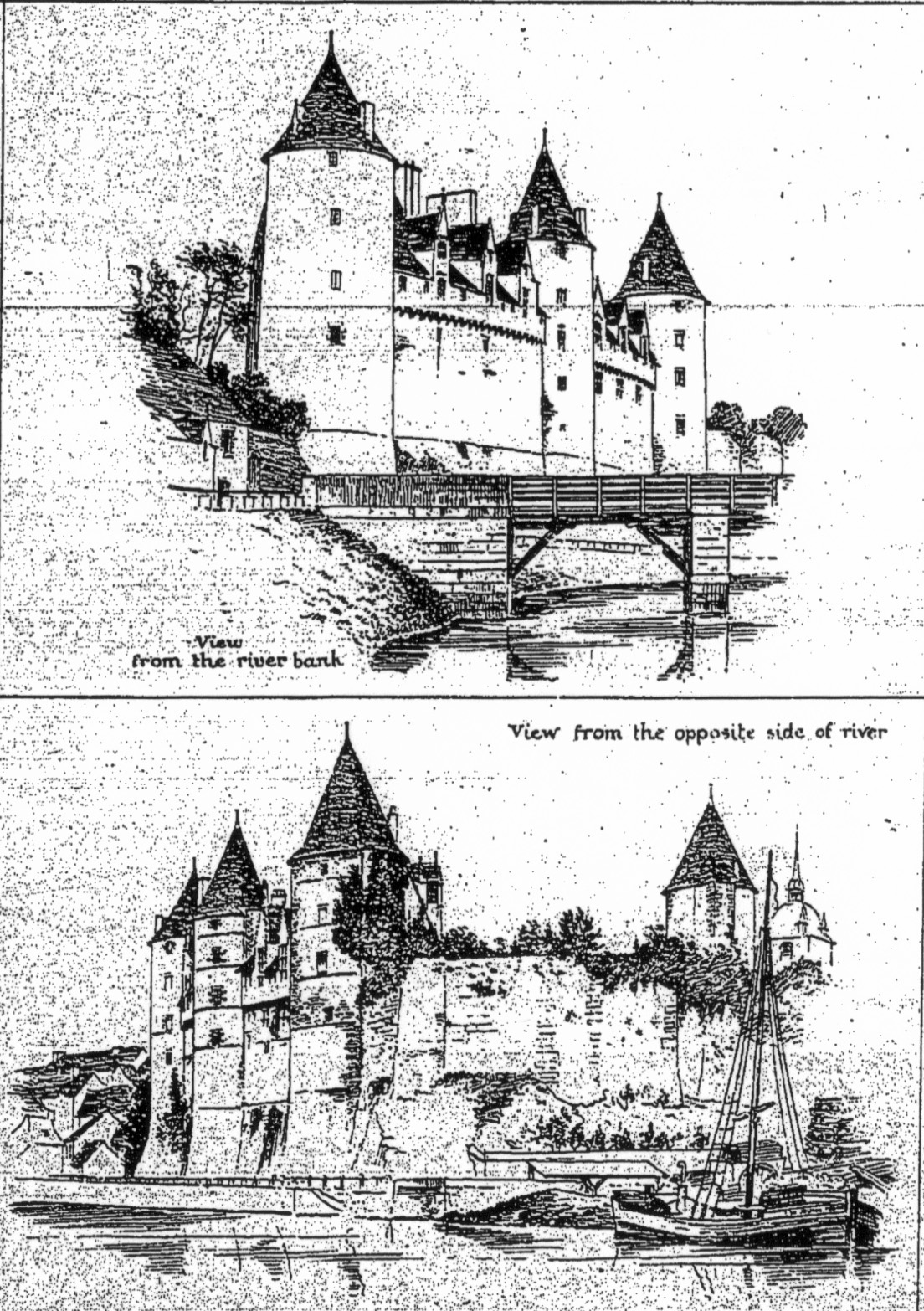

It was fitting that we should next visit the most quaint, yet most princely, of the ancient Palatial Châteaux of Bretagne. Never was a quainter town for Western Europe, with steep climbing streets, like those one has to mount in ascending to the elevated cities of Tuscany, or the mountain villages of Greece; as winding up from the river to the level of the château court, you pass between the very humblest, and sometimes uncleanly, dwellings to the atmosphere of almost royalty. (See our illustrations.)

It is not the extent of the demesne, but the unique perfection of architecture of its class, that makes it interesting. The side facing the river, l'Oust, is a grand specimen de l'architecture militaire du moyen âge, in all its frowning severity. The great façade is one of an irregular fortification, following exactly the course of the sinuosities of what once formed a lofty cliff rising vertically on the river side.

Every species of artifice has been used to add to its naturally defiant and commanding position. Three massive round towers guard this part; and the living rock below them is rounded and carped to their form, which, originally carrying down the simulated feet of the towers to beneath the river's level, presented an elevation of haughty grandeur, somewhat reduced by the present road, which forms the bank of the river, but still imposing, as the eye fails, without minute search, to detect where the masonry ceases, and the first impression is that the whole is a gigantic construction.

Many towers have been destroyed, but between these three, each of which is surmounted by a conical roof, the curtains are still perfect and capped by mâchicoulis, the spaces between which are composed of trilobed arches, with archivoltes en talon, and the dressings to the dormer windows repeat the same curves en talon.

Many towers have been destroyed, but between these three, each of which is surmounted by a conical roof, the curtains are still perfect and capped by mâchicoulis, the spaces between which are composed of trilobed arches, with archivoltes en talon, and the dressings to the dormer windows repeat the same curves en talon.On attaining the court the aspect is completely changed. The knights of Bretagne were as chivalrous as their neighbours of Normandy, and the signeurs of the family of Rohan were little less than feudal sovereigns, as shown by their fortress of Josselin, Rohan, and Pontivy, and the known customs of the great nobles of France in the middle ages.

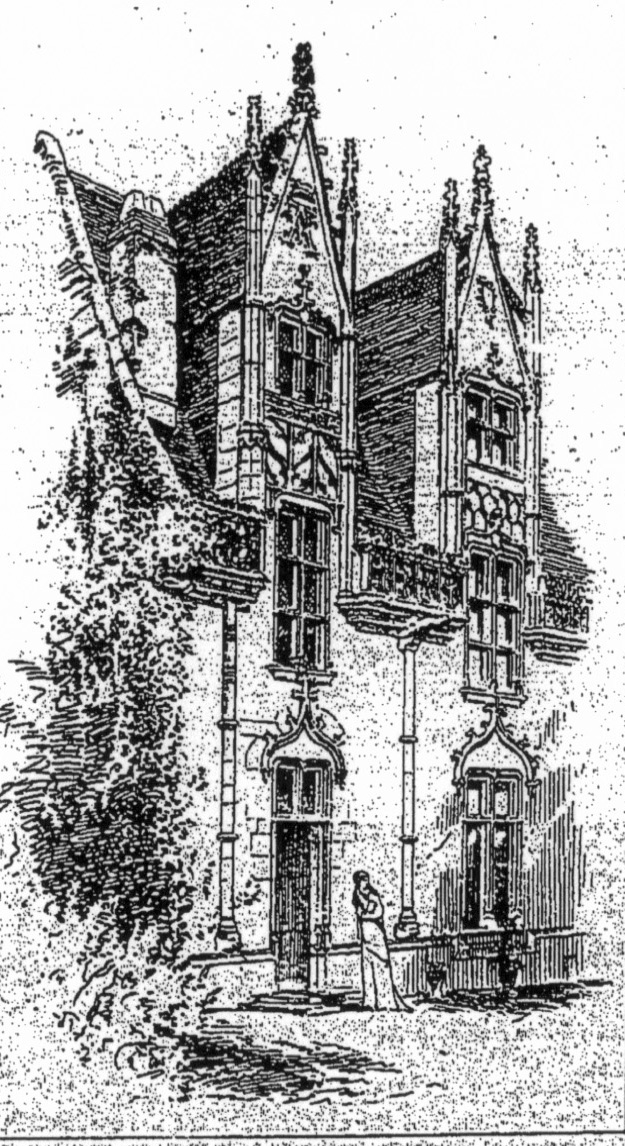

With these impressions vividly before us, we crossed the draw-bridge, and passing a grim and partly dismantled tower, stood among the rare shrubs in the richly planted cour d'honneur of the château. Not only did the velvet lawn, choice plants, and immaculate gravel drives wear an aspect of refinement at variance with the grim warrior look without, but the architecture here differs from the former as much as your knight, armed cap-à-pie for conflict, did from the troubadour or carpet knight, who was more at home in the duties of a chamberlain than a charge. There is nothing military in the elevation of the court. On the contrary, it belongs to the civil architecture of France, of the last period of that termed by the French Ogivale, in all its ornementation dè luxe.

Dragons and serpents gambol over it in every fantastic shape. The decorations on the parapets are inscriptions, the letters and designs of which are formed of entwined serpents. The whole architecture of Bretagne of this date, civil and ecclesiastical, is an elaborate enrichment composed of dragons and serpents. Did we find this only as a decorative feature, it might be supposed that it was simply an overflow of imaginative Arthurian art. But when we discover the serpent and dragon associated with their most sacred traditions, as at St. Pol de Léon, and elsewhere, and always the destruction of these creatures and the supremacy of the cross, it is not, I think, difficult to see in the traditions and emblems Christianity triumphant over a previous serpent theocracy.

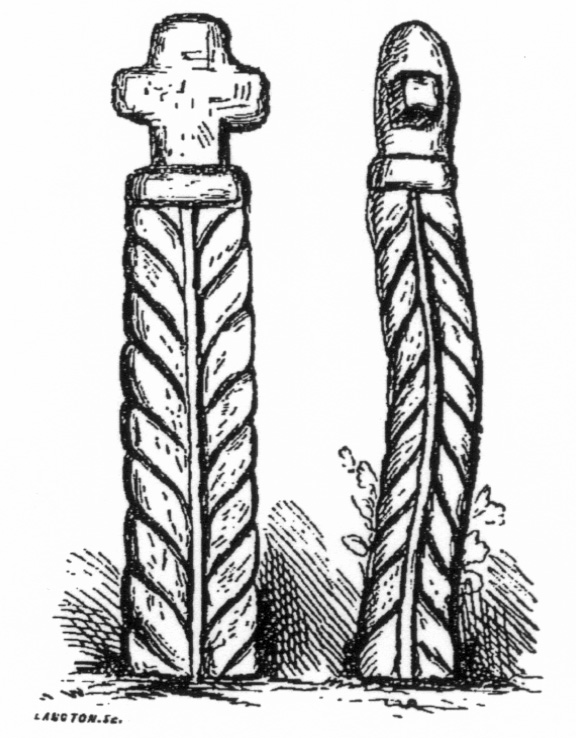

Dr. John Smith, a clergyman located, during the last century, in the highlands of Scotland, gives, from information practically gleaned by himself, from those among whom he officiated, a complete statement of Gaelic serpent mythology. He describes their "Isurim" or Hades, in which the most evil were believed to be "immersed in snakes." A suffering supposed to become less by degrees, according to diminished culpability. Devices of this kind are found in the oldest remains of Bretagne; in their ancient chambers, as at Gavr'-Inis, and in their soustetterrains, now ecclesiastical crypts, as at Lanmeur. An earthwork, representing a most symmetrical serpent, with a large spheroidal head, on which was a circle of stones, was discovered by a lady of our party on the Lande de Lanvaux, and similar works were afterwards found by me. The very menhirs have been sculptured to the rude device.

"The trail of the serpent is over them all," nor is its influence less marked in the history of the courtly family of Rohan.

The kindness with which the great turn out of their comfortable rooms to give gratification to casual visitors is, I think, hardly appreciated. His Grace of Rohan received us politely, and leaving us in the hands of his chamberlain, strolled in the grounds while we inspected his palace. He has all the bonhomie of an English country gentleman, and appeared to delight more in the princely elegance of his handsome son, le Prince de Léon, than in his own importance. The latter, as affable as any prince of faery, suspended a drive he was about taking [sic] that his pretty little daughter might inspect a câmera lucérna one of the ladies of our party had adjusted to take some details of the elevation, and when her numerous questions had been answered, drove off with a polite bow and a pleasant adieu. They are sterling people these Ducs de Rohan; and one cannot but feel that the poor cardinal was as much maligned as the unfortunate French queen, when one recalls the story of the filched jewels in Carlyle's graphic wording. Consider, he says, the unutterable business of the diamond necklace, the Sicilian Cagliostro, the milliner, Dame de Lamotte, the highest church dignitaries waltzing in Walpurgis dance; a whole Satan's invisible world displayed, working there continually under the daylight visible one. The Throne brought into scandalous collision with the Treadmill, astonished Europe rings with the mystery for ten months, and sees only corruption among the lofty and the low. Weep, poor Queen, thy first tears of unmixed wretchedness. Thy fair name has been tarnished by foul breath. Thou shalt be loved and pitied again by living hearts, only when a new generation has been born, and thy own heart lies cold, cured of all its sorrows. And then dwelling on the design of the wondrous bauble, the lambent Zodiacal or Aurora Borealis fire it emitted, he says—All these on a neck of snow slight-tingled with rose bloom, and within it royal Life: amidst the blaze of lustres; in sylphish movements, esplégleries, coquetteries, and minuet mazes, with every movement a flash of star rainbow colours, bright almost as the movements of the fair young soul it emblems! A glorious ornament fit only for the Sultana of the World. Indeed only attainable by such; for it was valued at 1,800,000 "livres;" (francs? say) in round numbers, and sterling money between eighty and ninety thousand pounds.

Perhaps neither the milliner nor the Sicilian knew much about it. What, if like Lancelot's prize and gift to Guinevere—>

. . . "she seized,For the necklace was never traced, and never found.

And, thro' the casement standing wide for heat,

Flung them, and down they flash'd, and smote the stream.

Then from the smitten surface flash'd, as it were,

Diamonds to meet them, and they passed away." (?)

And so we leave the sweet château, the quaint churces, and the romantic town of Josselin, which formerly placed at defiance our own Henry II. of England in 1168.

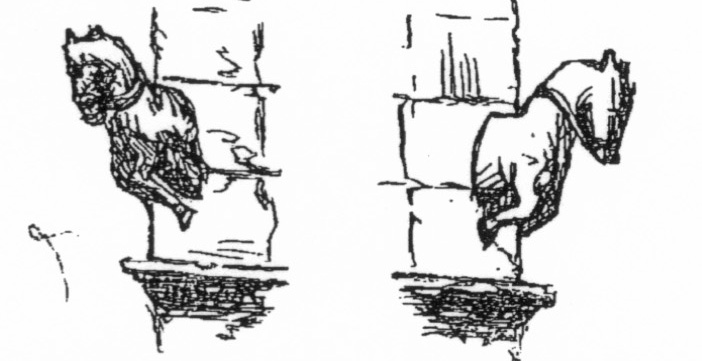

I have selected this, as one of the many places of real history, which abound in Bretagne, because it is one of the finest, and is still occupied. But you may revel among magnificent châteaux, fifteenth century churches, and remains teaming with England's history, as well as that of France; or wander among the monuments of a race older than Rome, and find the sites of Phœnician colonies on the shores of Bretagne. Among such places Penmarc'h is prominent, and any who feel interested in the subject will find many references to it in the British Archæological Journal for March last. The name means "horse's head."

It was so named from a natural simulation of the head of a horse on the shore, a favourite symbol of the Phœnicians, as shown when, on their finding a similar emblem at Carthage, they made it an object of worship. The parish church is decorated with horses' heads.

It was so named from a natural simulation of the head of a horse on the shore, a favourite symbol of the Phœnicians, as shown when, on their finding a similar emblem at Carthage, they made it an object of worship. The parish church is decorated with horses' heads.The richly embroidered collar of the natives is peculiar to that neighbourhood. It is quite Oriental, almost Indian, in its elaborate embroidery, and assimilates to the gold Iodan Moran, which some have thought borrowed from the urim and thummin, and has now become a fashionable article of ladies' costume.

There is, however, no greater charm to be found than in the unsophisticated rural districts, which take us back to pictures of our English forefathers, when a diminutive cottage formed the country rectory, its inmate "passing rich at forty pounds a year." We found the peasantry often full of kindly feelings, one poor woman going miles out of her way to show us the road, though, as she told us afterwards, her children were crying for their supper. Of course we saw they had the means for a better one than usual. I can hardly leave this district without pointing out that one of the churches at Josselin still preserves the name "la Huguenoterie," the Bretons having been prominent for Protestantism, as the edict of Nantes shows. Some of the modes of escape, on the revocation of that edict, would be amusing, were it not for the painful features of the case. One man, the benefits of whose ingenious mind this country at the present day enjoys, came over to England in a cask. I am myself a descendant of one of the Huguenot families long settled in this country, and felt it no small honour a few years ago to be called on by the Association Française to read a paper, on my discoveries in Scotland, in the city of Nantes itself. The loss to France, and consequent gain to England, by so many ingenious and plodding men being transferred to these shores will be admitted, one of the features of British art industry, that of silk weaving, being for a long time governed almost entirely by the settlers in Spitalfields! Nor were they less prominent in the highest productions in porcelain; and our first financial circle holds many of their names to this day. We have never allowed our aged or infirm to fall upon the parochial or other relief of this country, but, while settling as industrious citizens, have taken charge of our poor and incapable as if still wanderers and sojourners, and having no abiding city to dwell in. The quaint chapiters in the French Protestant church at Canterbury show the love for that species of decoration which, whether as Romanists or Protestants, the Breton mind was enamoured of.

Among other interesting advantages our party had on one occasion, was the presence of a pupil of Mr. Emile Souvestre, the best writer on Breton matters. And the suggestions of the first men of science in Brittany, Dr. Closmadeuc, M. Le Men, M. Geslin de Bourgogne, and others, made our endeavours full of result.

Going almost south from Josselin down to the mouth of the Loire, I encountered also, in that strange spot referred to by Strabo, and Diodorus Siculus, as a place retaining the ancient rites of the Pagan Phœnicians, the old armorial bearings of my family, which are unusual, consisting of a combination of the mermaid, lion, and dragon. And this confirmed me in a good deal of evidence I had before acquired that the origin of my ancestors was Phœnician, which the dragon and mermaid seem to portray.

I must here draw your attention to the salt heaps of this neighbourhood. The larger ones are exactly in the form of the nurhage of Sardinia and similar structures in Calabria and Otranto, districts in which I have stretched many of them, as represented on the diagrams. An indication, I think, of the course of travel taken by these people, who are admitted to be strangers and settlers. The white aspect of these heaps arises from their being covered with light coloured clay till ready for market.

Before giving you another, and perhaps the grandest of all the traditions of Brittany, which we will seek in the far west, let me devote a few minutes to the special features in which this society is interested. In a country still so primitive, though so close to our shores, we are able to look back on any question affecting the great international tastes and pursuits of the families of Western Europe; so that while travelling through their often beautiful rural districts, we will take a glance at the people themselves.

The sister branch of art, to which I referred at the outset—the representation of nature as distinct from that of sculpture—struggled up with difficulty, and was almost choked by the thorns and briars of busy commerce and its money-seeking on the one hand, and an unapproving ecclesiastical, and an unappreciative, unliterary, and agricultural majority on the other. Taking us numerically, the English are, perhaps, the most reading people; while artistically, judging from the products of its schools, England may be said to be the grand nation for landscape painting, and for the representation of humble but true life through painting, in the world. There must be some affinity, therefore, between literature and the fine arts.

Thus we find, in its early days, art was only appreciated, only understood by the great—not because they were great, still less simply because they were wealthy, but because they were refined, because they were literary. When art first sprung up, the only literary communities were ecclesiastical, and, short of princes, they were the most able to encourage painters in a pecuniary sense. Hence the great tendency of art to ecclesiastical representation. But growth once given, art could not exist in servitude, and the arena of pictorial religion soon became too curtailed for it. Raphael, as I pointed out in my former lecture, was the first who opened the flood gates for a change from the curtailed church aspect. But quite apart from such heresy, encouraged, as it was, by Leo X. in Italy, the great feature in the German, Hanseatic, and Flemish schools was an exhibition of total freedom as to subject. Rubens'2 threw off all trammels with the drapery, but he dealt with the figure, which is not my subject. Van Goyen, Berchem, the Ruysdæls3 drank in and gave out the sweets of nature. Yet the early paintings, for the most part, treated of the activity of man, in goods laden quays, or sailing craft; or of his more solid productions, as the Venetian palaces, by Antonio Canal, or his Whitehall and Thames views. Cuypt4 basked on the sunny bank, and chewed the cud of contemplation with his cattle; and Old Crome showed us that a man could paint for love of his subject, probably, without any other recompense. This was love of nature, perhaps, more than of art, i.e., a desire to portray that which they loved. Gainsborough had to leave his landscapes for the paying face painting of his day, and Constable was not appreciated till our neighbours in France saw his excellence; nor was Wilson valued. All these produced pictures, for which abundant materials are still found in Brittany. The rural French are a non-reading people, and the Bretons are far behind them; except in large towns, book shops are unknown in France. The book-hawker alone conveys even pamphlets, and is consequently a great political agent, requiring special Government authority for his trade. In Brittany even he is looked coldly on. So that we are taken back, in domestic life, to the time when the English read only the Bible and the 'Vicar of Wakefield,' but worked vigorously like the Bretons of to-day. With our own reading our art schools have progressed, till we drink the enjoyment of an Elysium, in the rainbow poetry of a Turner; inhale, even in our London drawing-rooms, the fresh sea breezes, from a Hook; wander, in imagination, far over heathery hills with a Millais; punt it dreamily among sedge and water lilies, shaded from noontide heat with a C. J. Lewis; or let the flecked skies of a Birket Foster hide from us the higher heaven that we may gaze on one below.

The ancients had a certain amount of enjoyment in the scenes of nature, but it was all meretricious. Their river pleasure gardens bedecked the Tiber, as the Turkish race have in our own day ornamented the banks of the Bosphorus, known and appreciated by those who have passed a summer on its Sweet Waters. That was a wealthy luxury in Italy, as it is in this age in Turkey. The one dreamed away the sunny hours amid statues and the wine of Campania; the other abhors both, but achieves the same result by living beauties and the fumes of the narguileh. But the indolence of the luxurious Roman and of the Muslem are the same, with an interval of 2,000 years between, and the one is as certainly leading to annihilation, as the other was engulfed by it. The one nation was, the other is highly superstitious. In their outset they were both religious of the sword. How different the vigour that took delight, in first depicting what we have referred to—the industry of commerce, as in the laden barges of the Scheldt, or its results, in the palaces bordering the Venetian canals. These were, as we have seen, the first struggles of art from sacerdotal sway, till, when quite free, the sweets that the humblest can enjoy are seen represented on the canvas which becomes the magic reality of imagination; and the rich corn field, the sedgy river bank, the rugged mountain and the placid lake, the bleak moorland and the sunny beach, gnarled trees of the deep forest, and pretty rustic gardens, lead our thoughts through the lights and shades of nature. Nor does it rest there, beautiful as such terrestrial heavens are, when art throws into them its magic life, they are more so when occupied, when we see depicted the creatures formed to enjoy, and capable of enjoying, all these charms; when the painter's brush arouses our innate poetry, and with the harmony which feeds the eye wakes also, as it were, the very sounds of Orphic melody from nature's self, when, not the rocks, trees, and mountains are charmed, but seem to emit from themselves the rapture of a mystic music, unheard but felt, as the rushing torrent moves not, but seems to move, or the sunny landscape, or gambols of childhood make us breathe with a quicker or slower inspiration, as the mind and thought act upon the pulse.

Virgil began these delights in pagan verse, but his Tityrus reclining under the shade of a wide spreading beech tree, his Amarillis, Corydon, Galatea, and Alexis, his tender sheep and brousing goats, do they not tell us of the Syrian pastoral life of which there seem indications that his forefathers once led?5 His flowers and murmuring bees, the milk, butter, and honey, do they not wake an echo that we have heard before? See him as he was ere poetry made him her own, the astrologer, the diviner, the searcher into unholy rites and mysteries, and we see the dark labyrinth from which his brilliancy emerged.

Initiated into the gloomy mysteries of Egypt and Hetruria, in fact, into all the known religions of his day, he encountered one, the only one of all, the books of which pictured a happiness which he, a most favoured individual, just then enjoyed, while all his neighbours were exiled. Beneath his own vine, and his own fig tree, in a land flowing with wine, milk, and honey, he sang of flocks and herds, of streams gushing from the stony rock;—of whispering pines, and the sweet wood of the laurel, myrtle, and myrrh, nay of the Syrian rose,6 the rose of Sharon itself. Need we go further, to point out that he had met with the book of the MAKER, who, delighting in the beauty of his own works and enticing his creatures on to real enjoyment, promised to plant for them7 the pine, the box, the cedar, and the myrtle, and that the desert should rejoice and blossom as the rose? Its beauty and its poetry he saw at once. The other mysteries told of death and terrors, this alone proved its inspiration for it spake of joy and gladness. Convert, or perhaps all along a secret neophyte, confession was confiscation and death, for was it not made sacrilege to the gods? He had to choose between silence, and what was to him impiety, yet he burst forth into song, threw off all the canonical shackles, and, to avoid the charge of sacrilege, cast the nimbus of glory around temporal power, in the person of the emperor; a mockery too agreeable, too politically useful to be criticised; which left him free to sing, in metaphor, the pleasures of the gifts of Him who gave. Such was the reader of the ancient books freed from their rites; such is art under a dispensation, which, however ill we carry it out is, undoubtedly, the only dispensation of freedom and good will the world has ever seen. No other age has known enjoyment in the sweets of nature; no other poet, save he, except those living in the days of modern painters, ushered in by Thomson, has tuned his verse to extol the Paradise we dwell in.

But it is not so in Brittany, simple, kind, devout, and guileless people, the faces though placidly happy, seem to have little enjoyment. Their only change, variety or amusement, from the cares of toil, is the constantly recurring church going. They have, in fine, no amusement, and now-a-days, no poetry, no music, and no art.

It was not always so. In ancient days, when still the Syrian element was strong, all along the old route of traffic marked by their strange monuments, from Marseilles to Vannes, rang the songs of Provence and Armorica. In the latter, Merlin, a necromancer like Virgil, is described, as he was under the assumed Tityrus, as possessed of rich orchards, heavily laden with late and unplucked apples, guarded in his case by Amarillis, in Merlin's by a "beautiful nymph, with flowing hair and teeth brilliant as pearls amid roses." Strange too the same combat with the old serpent worship in each case. Everything, from one end of Brittany to another, is illustrative of triumph over the serpent; while Virgil proclaims as follows:—

The herds secure from lions safe shall live,A rather free translation after the style of Dryden. But there would be a day for Brittany yet were the people free to think, as they are to work. Intelligent, industrious, and nature lovers, art would find there a fair soil; and as the poetry of Virgil flew northwards to Lorraine, and was embodied by its painter, Claude, so the old songs of Provence would find an echo on a Breton's canvas. For whether we look at art in itself, or its history in a single master, its course is the same. As we see the vigorous birth from which the art of landscape painting sprung, we may trace its course, as in the works of Turner. Based, as in his early paintings on the process of solid industry, like the river scenes of the early Flemish and other kindred schools, he emerged into the classical as in his Liber Studiorum, and then, into what he created into a classical painting of his own, which might almost be termed the metaphysics of painting, it is so rarefied, so raised above the ordinary ether; and yet so true. But it must be seized by the imagination as well as a rapid hand, for it is transitory and evanescent as a dream. This fantasy of atmosphere, is also to be found in Brittany; as in the early morning when her grim monuments look like giantesque ghosts, assembled to repeat old Druid rites, and who have overstepped the hour of return. Or, as in a strange scene which overtook us at the ruined Château of Quinipily, when a statue, traditionally worshipped as a Phœnician idol, stood suddenly, in the very centre of the arch, of a rich rainbow born of a sunset shower. It seemed almost night, when a break in the heavy clouds behind us, in the west, let through a momentary ray on the falling drops, and the statue we were looking at. >

The cradle of the god with flowers be strewn,

The serpent progeny to death he'll give,

The sacred earth shall free from weeds be shown,

On each wild bush the Syrian rose be grown.

But though art flourishes, many an artist pines in this, our land of wealth. "We are not appreciated," say the men of thought and mind, or, as the world says, of enthusiasm; men who see the unseen, and hear the unheard, by others, "There is no avenir of life opening out to us, or, if we have trusted fortune, trusted too hopefully, that what we feel could be felt, and seen by others; have gone from our little quiet moorings, and as we sail down the stream of life, with our loved consort, see little skiffs starting up beside us on the ever-flowing stream, ah! how often do we find no freight to carry, no market for our merchandise." And what then? Is it nothing to hear that unheard, and see that unseen by others? Is it nothing to have souls that can mingle with the spirits of all that is good and beautiful around us? Shall we in bitter irony, like Turner in his sense of want of appreciation, do, as Ruskin points out he did; shall we make our pictures subservient to our spleen, by drawing the most perfect pigs8 in the foreground, to tell the public, that is all they can appreciate and that, that is the estimation we place on them?

No! Art has its high mission, even in all its branches. The painter, the sculptor, the poet, the architect, he who carries away the soul on sweet sounds, he whose great office is to guide, to teach, and to admonish, whether by religious, moral, or legislative code, should see that all is holy, pure, and refined. And though it may be, that among men, posterity alone will know or acknowledge us, still let us work and labour in that atmosphere of sweetness, which, like the fantasy of Turner's better paintings is filled with spirit eyes, and spirit whisperings, which tell us that we are known and appreciated by them, though our crude clay covering keeps us from their actual embrace.

No! when things seem out of harmony, let us again take a line, from Ruskin treating of Turner, who says, when he was in his greater mind, he saw "that the world however grave or sublime in some of its moods or passions, was nevertheless constructed entirely as it ought to be, and was a fair and noble world to live in and to draw in." And that when, as he sometimes seemed to think, the world was not quite all right, it was at those moments when he discovered also, that all was not right within himself.

No! art is one of those pure, and joyous outbursts of creature life and power, which tell us that we are of that Creator whose works we scan, measure, ponder on, and delight in. And when we feel the beautiful in nature's pictures, whether of the distant landscape, or the towering mountain; the watery ripple, or the forest glade, we feel and know that we have a joy unfelt in former ages; and that some great hand has removed half the veil once resting dismally on man; when every chasm, grove, or mountain, every fount or exhalation was sacred to a demon, or a to-be-propitiated deity; that some hand has opened a new life of liberty, and bids us behold the charms of earth, sea, and heaven and rejoice! nor bids in vain. We do see, love, and delight in such joys when we repeat, by art, the forms, the colours, the mysterious and ever varying tintings, free from the dread of a cruel power, feared as ever lurking to destroy. And yet, while we bask in the glories of such rays, bathe in the delicious coolness of such shadows, with a waywardness, as if the scared off demons had taken refuge within us, we turn from these and other pure and holy delights, to speculate on the dryest materialism, and on the most sombre and unsatisfactory as unsatisfying philosophy.

But Art stands firm, clearly defined as to its mission—that of a great civiliser, a gentle, tender refiner, for it is a study of the sweet and beautiful, a study of nature, a study of the works of God.

But we must glance at the people. An intensely wet day gave us an opportunity for postponing archæology, and seeing the ceremony of marriage, at Elven, and being present at the subsequent festivities. Beyond the actual ceremony, which all have seen on the Continent, the grand sight in Brittany is that of the ladies' rich and varied petticoats, which on this occasion were coquettishly displayed beneath the universal, and never otherwise disturbed sombre black dress. The festivities are microscopic repetitions of some of the great pardons or church festivals, of which, that of Saint Cornely, patron of cattle, and Saint Eloi, patron of horses, are perhaps the most remarkable.

In a less popular, and carefully studied paper, part of which appeared in the last Quarterly Journal of the British Archæological Association, I have gone into the classical origin of several of these customs, and many other points of deep interest, for which I have neither time now, nor, perhaps, would they be entertaining enough for a general audience.

I select a description, from a French writer, of one of these larger ceremonies, in which the danse ronde, always an accompaniment to the marriage festival, is introduced. Do not suppose the danse ronde is like our round dances. It assimilates to but is not the same as the Greek round dance, described in my letters from the East in the Oxford Journal, the Daily News, and other journals. A good illustration of this dance, which was drawn in Asia Minor in my presence, is now to be seen in the correspondent to the Illustrated London News, at Messrs. Colnghi's. In Brittany, it is a circle in which all join, going in or coming out at pleasure, without influencing the other dancers. Placed alternately male and female, all are arm-in-arm, a slow and heavy stamping sort of jig is continued to exhaustion, monotonous and unvaried as the weary music which forms the accompaniment; or the pungent everlasting refret of the one song, so it seems to me, they sing without ceasing, afterwards, with which the ears ring painfully for weeks. Some of the most peculiar ceremonies, are those I have referred to, in which the beasts and horses take their parts. The one I have selected seems to have been grafted on to the midsummer burnings of the Druids or Keltic priests, as it agrees with them in date, and the triple fire.

Imagine a quaint old Breton town, in all its picturesque effects of disjointed timber façades, irregular gables, and aged dormers nodding good night to each other, suddenly illuminated by the brilliant costumes of crowds of Armorican pilgrims, streaming in through each approach, as they radiate from every department of Brittany to a common centre—and then realise the following description.

At the church porch is seen the venerated Madona, covered with a brilliant robe of silk, surrounded with archangels arranged on a groundwork of ermine. The pilgrims have lighted wax tapers duly blessed; the young girls, have made offerings of their splendid heads of hair—an innocent sacrifice! Some are making the circuit of the church on their bare knees, on the stones; others earnestly kiss the metallic face of a saint; others stunning the ears by loudly repeating the sacred songs of the mountains; others suspending by a cord a fine peal of bells, ring incessant volleys, to which the naves of the church echo again, to fatigue. Everywhere there is a crowd, there is clamour, but everywhere, also, there is faith, there is prayer, there is goodwill.

In going from the church, the pilgrims are directed towards the fountain, at the summit of which the Virgin, supported on a symbolical cross, seems about to be thrust, to the very heaven. The consecrated water refreshes the dusty faces and limbs of the fatigued travellers, who lave their faces, arms, and shoulders in it. The sacred waters are dispensed by the poor, who receive abundant alms in return. A fair is held and booths erected, but the Bretons, paying no attention to the baubles and trifles exhibited, bend their ears, piously to listen to the recitals and complaints of mendicant pilgrims. In the suburbs of the town are pitched picturesque tents and bivouac resorts, at which, before long tables, sit many hundreds of convivial pilgrims. Before them are placed little fish, roasted in the open air, and vast casks of strong cider, of apparently inexhaustible capacity. There is no cessation of excitement when night approaches. Crowds walk under the trees. It is the holiday of the Armoricans. The legs of twenty years forget they have discharged twenty leagues, and la danse ronde is prolonged in capricious spirals. The townsfolk contemplate and admire, then emulation is raised, the people of each canton multiply their efforts, and high and low, grave and foolish, wrestle and struggle, heedless of grace. What matters the fatigue? The honour of their parish is in question. But the baton has struck a last appeal; it is nine o'clock; it is understood the procession must commence. Never in the memory of man has inclement weather prevented the sortie from the church. Though the morning may have poured a deluge, the evening was always bright with stars. All, even the most fatigued, who have retreated for rest to the hayfields surrounding the town, rouse themselves and take their places in the ranks. On going out the town is illuminated. The discordant music of the tribes of mountebanks, who have so far kept up an unceasing clamour, is at once hushed, and in lieu of it are heard the solemn chants of churchmen. The young girls, dressed in white, head the march; then the pilgrims, in a double and interminable file, advance like a grave cortége of phantoms. Each holds in one hand a chaplet, and in the other a lighted wax taper, great or small; the rich have torches, halfpenny candles the poor—all with pale visages, some screened with their long hair, others with white headdresses, which descend on each side like winding-sheets, pass slowly on, singing a Latin prayer. Finally appear the banners, the relics of saints, and the venerated figure. The tallest young men, with long hair, dressed in white robes, bear it on their firm shoulders, and proceed with lofty dignity, for this is an honour surpassing all others.

Three immense iron baskets are filled with wood, and placed in the form of a triangle. The clergy apply the fire successively to these. Then there is an enchanting spectacle. The illuminated houses sparkle, the wax candles of the pilgrims, moving here and there, chequer the bizarre and grandiose costumes of the Armoricans with strange reflections. The three braziers, after the smoke is dispersed, send up an immense flame, which mounts like a long serpent round the pole which bears, amid the clouds, the emblem of Mary. The fountain surmounted by her image, crowned with flowers, casts to heaven its collected jets in sheafs of water, which, falling in millions of drops, seem like rich pearls showered by the hands of the Virgin on her faithful servitors.

Not a vacant place to be seen. Ten thousand voices repeat the pious "Ora pro nobis." The lights on the earth make still more deep the dark blue of heaven, to which penetrate by faith in a thousand accents a universal prayer. The Breton faith is there exhibited in all its ardour and with all its poetry.

This is faith certainly, but not freedom. It is a fair representation of the "pardons" I have seen. As we have penetrated to one of their midnight ceremonies, let us stroll into rural recesses, unreached as yet even by the photographer. We have been amongst the people, and seen one of the pagan orgies broken up by the chant of the church, and terminated by the feu de joie. We return again to the noblesse.

Wandering over the broad prehistoric area of Saint Guyomard, in search of some magnificent menhirs that are found there, we came to a very small ancient chapel in a dense wood. The principal saint in it was Cornély, who has his sacred cows. What makes this very remarkable is that there seems to have been here, judging from the monoliths, a species of Carnac; and the chapel itself is constructed above a vast dolmen, the apse resting upon one of the huge blocks which projects on each side of the wall facing the east, and on the inside is at the necessary level for an altar—a strange feature in both the Latin and Greek churches, for in the latter, on removing the drapery, I have almost invariable found, in Greece, part of the shaft of a column of a former pagan temple under the altar table. A by-road now attracted attention, and the carriage being summoned, we pursued it to the fine old château of Brignac. Still inhabited, like Josselin, it has no national history, nor is its exterior nearly so ornate. But it has its own interesting history, and the richness of the carved oak beams in many a ruinous salon, in the great tower, showed what its grandeur was before the revolutionists backed and hammered away all they could reach to mutilate. Never was a fairer field for ghostly lady, or knightly spectre, every footstep resounding through the deserted corridors. Placed in sweet sylvan scenery, with, down below, a few rich pastures beside a meandering stream, the whole dotted with fine cattle, and surrounded with the distant hills once occupied by the ancient Redones, it forms a retreat too sweet, one would have hoped, to have been defiled by the destructive foot of the revolutionist. The external architecture of the windows is rich beyond expression, and when examined, found to be worked by original hands. No two sides are alike, and certainly no two windows; and yet so harmonious is the general effect that one has to look repeatedly before this is evident. The enrichments here, as at Josselin, are in high relief, and all carved in the hardest granite, with a finish and delicacy of detail our masons seldom produce in softer stone. One grille alone remains to show the jealous protection of its constructors.

The Countess de Montgermant received us most politely, and appeared not to look on us as strangers—a point that was presently explained, as she was at Josselin when we went over the château of the Duc de Rohan. Though evidently causing her some disappointment, we were obliged to decline her proffered hospitality to take refreshments, as the charms about us were too rich to be lost, and even the courtly bearing of the countess herself, in this fine old relic, much more appreciable as she showed us, first this, then that, point of interest in the various portions of the building, than it would have been in a state of quiescence at the head of a repast.

We cannot touch on any of the great monuments of the country. They are too grand in their mysterious and overwhelming import for a popular lecture. Many of them, including monoliths 40 feet high, are represented on diagrams on these walls, and have been treated of by me in a more suitable paper in the British Archæological Journal. One thing strikes me as peculiar with regard to them—they are, as a rule, the only things the travelling English go to see in Brittany, and the things, probably of which, having seen, they know least. IT is not from paucity but overflow of material that I decline to touch upon them; but I have visited them year by year, over and over again, in summer and in winter, in storm and sunshine, to seem them as they were seen by their ancient erectors, and have come away humbled at the great undertakings that barbarians carried out in reverence for their deities.

A general audience will perhaps take more interest in our visit the monastery of Abélard, that they may think over the sorrows of Héloise. But we must not waste time on known subjects.

The story of La Ville d'Is, although given by me in the journal above referred to, is too quaint and peculiar to be omitted, and may be doubly interesting to any who know our own local traditions about Harlech, the great inundations of that locality, the mystic supremacy of the kings of Dyvi, and the destruction of King Vortigern and his palace by fire from heaven.

The Breton story runs as follows:—The Ville d'Is was a beautiful and sumptuous city, placed in the Bay of Douarnenez, one of the inlets of the Atlantic, to the south of Brest. It was occupied by a wealthy population, ruled by King Gralon, a primitive patriarchal old sovereign, who had an extravagant and luxurious daughter. The French writers have dressed up the story with rich embellishments. She is represented as reclining on Oriental cushions, her person covered with pearls and jewels, and holding a discreditable court in the palace of her venerable and staid father.

The town was said to have been at a low level in the bay, and surrounded by a dyke, the sluices of which Gralon opened and closed once every month personally. The life of every inhabitant hung upon this practice, for which reason the king was bound to see to the matter, as it was too serious to be intrusted to any one else. For this purpose he wore, suspended to a gold chain round his neck, the silver key which unlocked the water gates. His daughter, the Princess Ahès, whose name was Dahut (i.e. the render or destroyer of the oak or parent tree) stole the key from her father, urged on by some discreditable people in her court, who ridiculed the tradition that the town would be destroyed if the gates were not locked, and who perhaps, as they were foreigners, desired its destruction through jealousy. An intensely brilliant scene is described in which beautiful slaves poured rich perfumes over their long hair and their arms, and adorned themselves with flowers to be fit for the presence of the great princess, and five branched lamps of flame reflected their rays in plates of gold. Dahut reclined on purple cushions on a throne, pearls interlaced in her dark hair, large circles of gold clasped her arms, a tunic without sleeves, or ceinture draped her to the feet, a collar of rich emeralds sparkled on her breast, bejewelled maidens fanned her temples, and she was plunged in a soft reverie. At her feet lay a handsome youth with long flaxen hair, some priests of the ancient faith chanted the praises of Keredwin, accompanied by soft music from lyres of ivory, an orgie commenced and was at its height when—the inundation by the ocean was announced. The old king was roused and his daughter sought refuge by sitting on his horse, the waves surrounded them, in vain the old king urged his steed, the waves rose, and a voice of one invisible proclaimed his life forfeit unless he cast off the "demon" who sat beside him. He did so, and the satisfied waves retired to enable the old king, whose locks of snow covered his shoulders, to escape. But the gilded domes of the temples and palaces disappeared, though at low tides, it is said, even now, the walls of the city may be traced. Judging from the older tales of the fishermen, the French writers head the legend with a translation from Thomas Moore, slightly altered:—

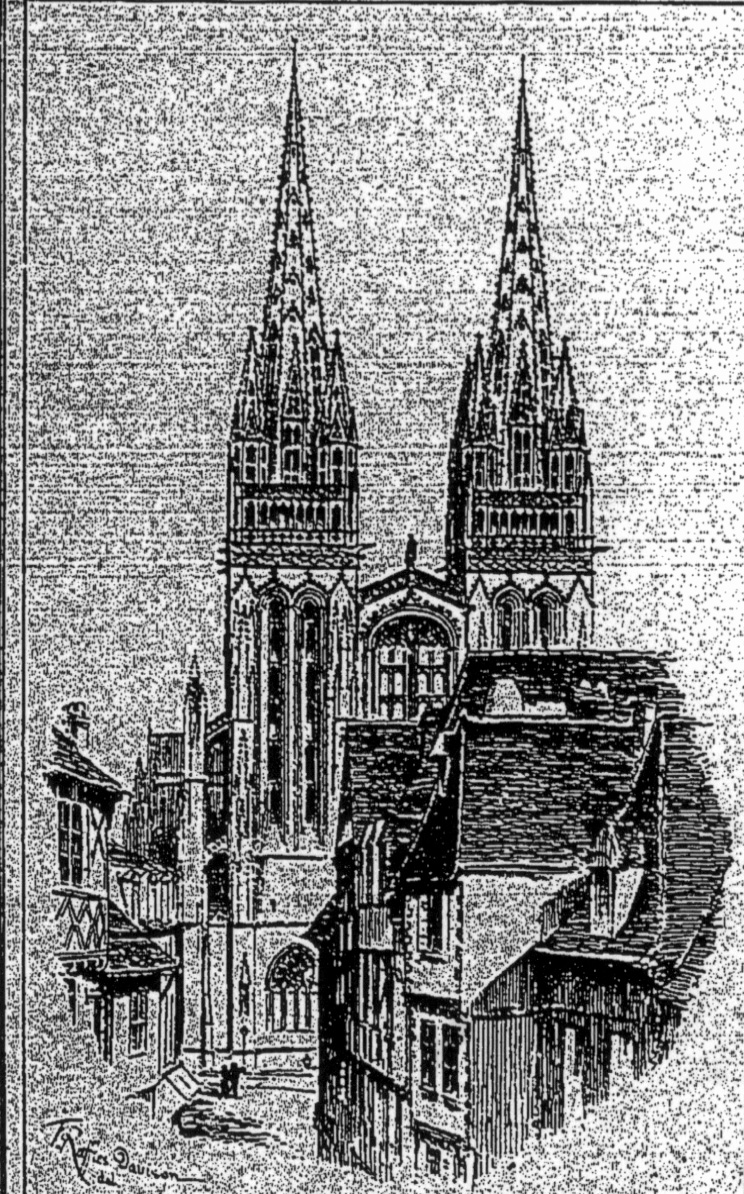

"In the soft blue sea, 'mid the slanting raysGralon escaped, and in gratitude founded the bishoprick of Quimper. He is seen mounted on his charger, between the beautiful spires of the cathedral, an illustration of which will appear among others in the British Architect. A former tower of this cathedral, covered with lead, was destroyed by a "Red Demon," which descended in the presence of the whole community in a cloud of fire, and caused the destruction. This legend was gravely recorded by the curé, who describes himself as an eye-witness of the event, and in particular of the red Demon. The souls of Dahut and Gralon are often seen by the Breton peasants in the form of two large birds, which disappear when approached.

Of the evening sun declining,

You may see the round towers of other days

In the wave beneath you shining."

Another strange legend we have in the sand-buried city of Escoublac. An old man and a young woman one day entered the town and solicited food and rest at the nearest house. Repulsed, they went to the next, and so on till they had visited every house with no success. The old man was seen to be angry; the young woman, joining her hands, was observed to entreat him, but to no purpose. He drew three hairs from his beard, and cast them in the sea. He and his companion then visibly ascended to heaven, and so violent a wind blew from the west that the next morning the town was not to be found, being buried with its guilty inhabitants. The Bretons do not see the profanity in their asserting that these persons were the Eternal Father and the Virgin Mary.

But enough of that. We cannot quit Brittany without a mention of King Arthur. His region is that facing England, indeed, opposite our own Arthurian district. With us he is said to have been buried at Avalon, the Isle of Apples (Glastonbury). With the Bretons at Avalon—in Brittany. But where was Avalon?

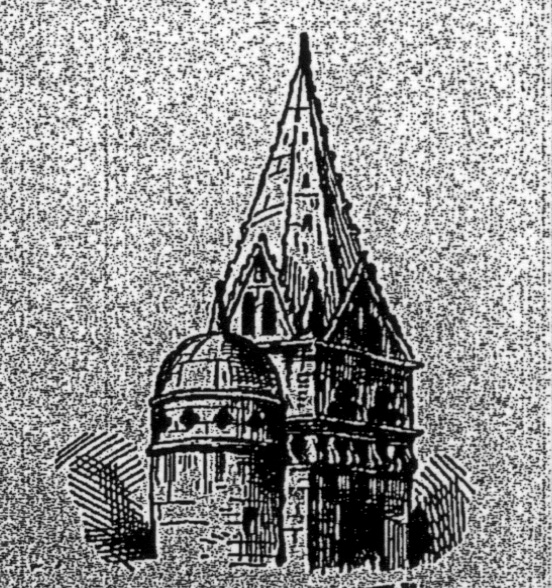

The whole district east of that dedicated to Saint Eloi, who I have shown, in the "British Archaelogical Journal," was the same as the modern Greek αγωις Ελιας;, and the ancient Ηλιος, (the sun), to whom, under the name of the saint, the sacred horses are still dedicated in Brittany, may be said to be Arthurian, as far as the ancient cathedral of Tréguier. You have legends of encounters with the dragon all along; the splendid foundation of St. Pol de Léon for having overcome him; a dragon festival at St. Jean du Doigt; a severe fight at St. Michel-enGrève, the tower of which church, as shown in illustration, is an interesting object, and somewhere in the distrct—Avalon. Miss M. Betham-Edwards recounted, in "Fraser's Magazine," her failing to discover the place. We followed in her steps, inquired of the same officials, and obtained the same hopeless answers.

I must read you an extract from that talented authoress, who gilds and tints her subject prettily, a fascination I also should have liked to indulge in but that, within the hour, I wanted to give you more a sketch of Brittany, and leave you to colour it at leisure. She says—

"I think I went more for Tennyson's sake than anything else, though when I got there no one could tell me which of the many islands lying off the coast was Aval or Avalon. Full of vague expectation, therefore, and having made up my mind that I was to see, if not the real Avalon, at least the place where Avalon was supposed to be. I set off for the coast. The day was now exquisite, with pearly clouds floating across a pale blue sky, and lovely lights and shadows in the mellowing woods and hedges through which we drove. We are soon enraptured at the prospect before us. A little way off lay the Seven Islands, amethystine between a turquoise sky and lapis lazuli sea. Not a breath is stirring this soft summer day, yet the waves here are never at rest, and dark with perpetual murmur against the glowing sea walls. As we wander along the edge of the cliffs, the full splendor and weirdness of the scene became apparent.

Which of all those lovely islands is Avalon?My guide does not know, but thinks it is the Ile Tomé; and the old keeper of the lighthouse, when I made him understand what I wanted, shook his head and said, 'Le Roi Arthür—il n'est pas de ce pays.' Neither the French guide books nor the English indicate it; the maps do not designate it. A most cultivated native of the locality said he thought it was not to be identified. An old traveller in Finistère, writing many years ago, says, King Arthur was buried in the Isle of Aval or Avalon, lying off the coast not far from his family residence of Kerduel, so famous in the legends of the Round Table. But neither from books nor hearsay could I satisfy my curiosity as to which of the dreamy looking islands before me was Avalon."

'Where I would heal me of my grievious wound.'

Well, I determined to visit successively every island along the north coast and examine each carefully. Geological changes have been steadily varying the face of the country all round the coasts of Armorica. An elaborate work has been published on this subject, with maps of the past and present aspects, by Mons. Desjardins, of the Institute of France. This gentleman gives the grand features of change along the coast, but these do not include the one district I was interested in, so I determined to search, upon his careful and effective system, the geology of the coast, for ancient Avalon,

"Where falls not hail or rain or any snow,We visited les Sept Iles, those amethystine dreamy spots of heavenly-looking land Miss Edwards so well describes, but did not visit; then many others, and one day at Ile Grande, where we found a most remarkable dolmen, having an enclosed court round it, formed by a rude but royal peristalith, and where the people got up a special dance for our edification, we once more put the question; put fruitlessly five hundred times before,

Nor ever wind blows loudly but it lies,

Deep-meadowed, happy, fair, with orchard lawns,

And bowery hollows crowned with summer seas."

"Where is Avalon?"It was then the real Avalon. We went to it at once. There was but one house, and no trees. On approaching the house we were greeted with—"Welcome to Aval, Isle of Apples." "Where are your apple trees?" "There are none." "How is that?" "Look how the sea has washed away the land." "True;" and it was clear that the present Aval was not long since a portion of Ile Grande. Aval and the Grand Island were then one, and the grand royal dolmen was on the former Avalon. But there are no trees on either, save a few planted by the Marquis de Champagni. How then about the apples?

"Close before you," said a fisherman.

"Where?"

"Close, here," pointing to a rocky island separated from us by a narrow channel.

"Is that Avalon?"

"Yes."

"Do you know the meaning of the name?"

"Yes. The Isle of Apples." Others gave the same answers.

The shores all round sloped deeply to the water, showing "lawns" and "bowery" orchard clothed "hollows" in which the islands lay buried. The search over the island now became intensely exciting, and, guess my joy, when I discovered a stone, such as I had seen near ancient temples in Greece; long out of use, even in the East, and there formerly used for crushing olives. And this stone, "What is it?" "We don't know. It is very ancient." It had been built into a wall. "Can I buy that stone?" "Yes." And I bought it. I then visited the orchards of the shore. I found a stone like it but disused and put away. With it was a neolithic celt, a rubbing stone, and a stone for shaping celts. I bought them all. What is this stone? "It was used in old times for pressing apples." "I thought so." The stone is very heavy, and was transported for me from the island at much expense. It could never have been taken there in late times, for the island abounds in granite and building material. It had been formed for use upon the spot. Formed for crushing the former apples of Avalon. The stone is now in my grounds at Chelsea, and Arthur's tomb forms part of my estate in ancient Avalon, for the spot became sacred to me, and I purchased an estate there at once. I found one of these olive-pressing stones on the Acropolis, at Athens; one on the very summit of Syra, no doubt once the position of a sacred grove; and several in other Cyclades. One reason why I consider the enclosing peristalith implies the sacred and royal in such cases is, that the Cyclades which formed a crowning circle or enclosure round the sacred Delos, a grand natural peristalith, in short, were so named κυκλος (circulus), from the fact, as stated by Strabo, Pliny, and others. The royal peristalith, being formed of high stones, is quite exceptional, if not indeed unique in dolmens, and my personal examination of that excavated by Dr. Schliemann at Mycenæ leads me to conclude that each had the same intention, that of distinguishing royalty. Close by is an estate of the Marquis of Champagni, who resides at Kerduel, some miles inland. Tradition connects Kerduel with Arthur's court, residence, and birthplace; and Avalon has always been allowed to have been place of his burial. The dolmen is figured in the British Archæological Journal for March last. But the view I now exhibit shows the peristalith to much greater advantage. Dolmens and burial-mounds surrounded by stones, are found slightly scattered throughout the dolmen district. I have found them at Clava, in Scotland, and such surrounding is fully described by me, in my paper read before the Royal Institute of British Architects on the 19th of May, 1873, as being a feature of the vast serpent mound at Loch Nell. I have found such surroundings also on the Wiltshire Downs, and in Algeria they have sometimes two and even three lithic enclosures; but nearly, if not all, these are either mere boulders, placed as a line of demarcation, or a sacred circle; or where placed upright, comparatively small stones, acting as a retaining wall to the base of a mound surrounding the chamber. The stones forming the peristalith in question are large large slabs, part of an enclosure, once as high and perfect as the dolmen itself; placed in a long oblong, parallel with the sides of the dolmen, and differing from those of Mycenæ only in the form, the latter being circular. There could have been no mound here, as the surface is nearly all granite, very slightly covered with soil. The collection of earth for a mound would have been difficult, and its remains certainly apparent. The burial was, no doubt, in a natural cavity of the granite beneath the dolmen, and the court enclosed by the peristalith, a place of concourse. A rude and old bénitier, dug up from a similar hollow near the dolmen, indicates a previous and rude chapel. I think it highly probable that the burial of the so-called King Arthur took place in a pre-existing dolmen, and the peristalith was to commemorate the royal interment. That at Mycenæ is also of much later date than Mycenæ itself. There is a small double upright peristalith near Oban, in Scotland, which Dr. Angus Smith and I examined, but it is circular, the lines being concentric, and appears to have had no closed chamber inside—it is more like a miniature of Stonehenge.

Among illustrations in the above-mentioned and other journals are views of the remarkable menhir, sculptured into a serpentine form, near Tregastel, in the vicinity of Aval; as well as some fine reticulated sculpture in granite, in the porch of the ancient Cathedral of Trèguier; and some of the rich embroidery of the Breton costume worn near Penmarc'h; as well as the sculptured horses' heads which decorate the church tower of that town. But the quaintest of all is the great menhir, which commands the way to the Grand Island, now literally covered with sculptured masonic emblems, in juxtaposition with such florid Christian exhibitions, as the reed and sponge, hammer and nails, dice and lot cast garment, and in the centre a life-size representation of the great death on Calvary, all in supposed proper colours. The fullest illustrations, including views of the Cathedral of Quimper, and the magnificent chateau at Josselin, will be found in the British Architect, together with a verbatim report of this lecture, and illustrations of the birthplace and burial of King Arthur in the Builder, Building News, &c.

Returning homewards we pass near Mont Saint Michel. Saint Michael lords it over all these places in England and Brittany; and he has always the conquered dragon beneath him. At Glastonbury, at Mount's Bay in Cornwall, and everywhere Arthurian, is Saint Michael, as St. George is elsewhere. Never was a more imposing or romantically built fane than that in Normandy. It rises in all the fantasy of a dream, and all the majesty of reality. Its wondrous view, its gorgeous chapels, dark crypts, and secret passages, make it a place never to be forgotten. The chapel of the Black Virgin is the most impressing. But the tale more so still. The present figure is magnificently attired, and as large as life, but the monk who took us over the edifice, which recalls the fairy stories of the castles of great magicians, told us of a much more ancient and much smaller figure in black oak, which was replaced by the present one. From the description, the truthfulness of the narrator is apparent, as the Black Virgin of Loretto, still existing, and the original figure of Diana of Ephesus, in ebony, were just so represented. The Loretto figure is reported to have crossed the Adriatic miraculously, and to have come originally from Palestine. Its exodus from Greece, I can well imagine—as I believe these sacred black figures, of which several reached Western Europe, were former deities of Greece or Asia, either similar to, or the actual wooden figures, referred to by Pausanias as being in the sacred groves and temples. It is very remarkable that one of the titles given to such a figure of Proserpine, who was necessarily connected with black or darkness, was, as stated by Pausanias, "the holy Virgin." The custom of importation was kept up in the Latin church, as in Grotta Ferrata, which has one of these images, an old Greek painting for an altar piece, and the service in which is still performed in Greek, the whole being not far distant from Monte Dracone, near Tusculum, while the figure mentioned by Pausanias, was in a grove dedicated to the Python destroyer; in which place, in Greece, I found a large lithic arrangement in the form of a serpent some hundred feet in length.

And now we have made our hasty tour in Brittany. We have glanced at its churches and châteaux, its manners and customs, its sweet woodlands and splendid coasts. I have avoided the ancient monuments because I wanted to bring the modern Breton before you.

Many a pleasant scene I could show of orchards and homesteads, winding rivers, and crumbling fortresses, Tonquédec, Coetfrec, Sucinio; of monuments erected, perhaps, in the age of Abraham, and sweet inlets of the sea; and the weird cross of the Pagan assoilised for Christian rites; of bent church apse and heathen fanes, now sacred chapels. Many a fairy island along the coast, or within the mysterious inland sea, the Morbihan, whose rich blue waters, dotted with the dark, brown-red sails of the craft, recall the leather sails of the fleet of the Veneti destroyed by Cæsar. The number of islands in this inland sea is reverently believed to be the same as the days in the year. Of every size, form, and variety, some are found bearing fair towns and churches, some minor hamlets, some a single farm, and others only grass and a sheep cot. Many are uninhabited, and of these again, as well as the larger ones, not a few bear the temples, tombs, and traditions of the old pagan inhabitants. The pencil was always at work, and did time permit, we could entertain you with the thousand and one scraps and figurings in our sketch books; much time being saved when each person can take a different object. The diagrams exhibited are enlargements from them. It is now, however, necessary even to attempt to satisfy your curiosity on this point, assuming I have been able to arouse it, because some exquisite sketches and drawings will very soon be submitted to the public, by that gentle artist Mr. Birket Foster, who, while giving simple facts, is able to carry the feelings away in rapture.

We have endeavoured to show Brittany as it is; not the realisation of the dream of an antiquary; no diving into the far past; and yet it gives us primitive man, even at our doors. Nor is it there alone. The Spaniards have for centuries been sinking back to that condition, and the Italians, even in this day, are, in some parts, merely bandits. Greece, Egypt, the fair fields of Asia, and even Palestine, are as much uncivilised. Barbarism has, in short, crept over the whole of the first tracks of civilisation to Brittany and Britain. Since the efforts of the late king, the art of northern and central Italy has exhibited a greater freedom, and hence more sweetness. Its former art was under ecclesiastical sway, and where the beauty of the human form was attained, it was borrowed from the sensual theocracy of ancient Greece. One trammelled quite as much as the other, for the Greeks could imagine no gods but men, who, they asserted, were their own ancestors. Hence Greeks and Romans claimed a divine genealogy, and the artist was urged to produce godlike men. Overstraining religious authority in any denomination produces a similar result. We have almost as distinct a picture of primitive man in our own Hebrides, where the rule of the Presbytery is too severe. There is no elasticity for the mind, no generous feeling of imparting to others the charms we see and love in the beauties of creation, but instead of it, a heavy dogged selfishness where there is enjoyment, and of stupidity where there is none. It is in the freest states that we have the purest art. Whether we look at the châteauxs or churches of Brittany, we find that the art of architecture, which they undoubtedly possessed in no small degree, was an art under ecclesiastical sway; and for that purpose it was good, but it went to further. Pure art and pure religion have an affinity. They both speak to us from the better side of the heart. They have each their inspiration. They both grow weak and wither under an amount of human patronage which checks their freedom, their spontaneity. Even the wondrous fabrics of the middle ages, ecclesiastical though they were, would never have been raised but for their makers breaking the trammels others were under, and rallying beneath the banner of free-masonry. The same policy which guided Leo X. in the licence he gave to Raphael was general in their case, and dispensations and indemnities were freely granted by successive popes confirming their independence. The Breton legends, whether of their pagan or Christian forefathers, as of the destruction of the towns of Is and Escoublac, or the Christian triumph over the Dragon, speak of avenging deities; or, as the French writers so often express it, of the retributions of a Sodom and Gomorrah. There is no joyousness, no elasticity.

In the last official report of the Social Science Congress at Aberdeen will be found a statement by me of the great civilising effect which free Christian nature art would work among our artisans and hand producers generally, if properly dealt with. We want to get at our people with humanizing means, for at present they keep almost as clear of our picture galleries as they do of our churches.

The explorations for the above observations are not to be made with entire freedom from danger, not from the people, but from the primitive condition of the country, in some parts.

We ascend the triple-peaked mountain, Méné Hom, to see the sites of old Druid ceremonies, and visit the Bay of Douarnenez, where the town of Is had flourished. A rabid wolf crossed our path more than once—indeed, must have accompanied us the whole way. We heard of the wolves in various districts. It was market-day, and the quaintly-costumed peasants, of whom the women wore a cap formed into a horn, generally yellow in colour, and vividly recalling a certain Eastern head-dress, were streaming up from the Bay of Douarnenez, over the spurs of the Méné Hom, to Chataulin.

We could well imagine from this the scenes when they pressed up the mountain to witness the Druid rites and sacrifices. But it was only in imagination. We had no idea that a sacrifice as great, arising from the primitive barbarism of their country, was even then going on. That men, women, and children, horses and cattle, were being slaughtered in a great hecatomb to the deity of the wild Landes. But, on our return to Chataulin, there was a painful scene. The market people were all excited; groups of men, examining the bleeding wounds of their lacerated comrades, were seen in several directions, and we then heard, for the first time, of the rabid condition of the wolf. There was some account of it in the London papers at the time, but I have before me a letter from Chataulin which states that up to January last, a period of about two months from the date of our last visit, out of seventeen persons bitten eight had died of hydrophobia, several were ill, and thirty head of cattle and a horse were also dead. We saw the wolf dissected at the Prefecture, and were thankful that we could traverse our hills and valleys in search of subjects for true, Christian, loving, gentle art, without risking acquaintance with the morgue or madness.

Not to conclude with so lugubrious a tale, I must relate another adventure, in which I was arrested for a German spy.

I had been devoting much time, after several years of exploration, to tracing, if it could be traced, ancient Avalon, with the agreeable result I have laid before you. Archæology takes one into strange places, and no doubt a person poking about secluded spots, examining ancient landmarks, and sundry things, the interest in which is inconceivable to the natives, is a rather suspicious person. I found myself under the eye of a very gentlemanly man more than once, who, finally intending to arrest me, was kind enough to do so in the dead of the night, and thereby saved me from street wonder. On a bitterly cold winter's night, at ten o'clock, I had to turn out and accompany a file of gendarmes to the Prefecture. I was cross-questioned for an hour, my assertions that I was an Englishman being treated with contempt. I was then ushered into a more private chamber probably for committal, when I saw that my judge, the Prefect, was the gentlemanly man who had been observing me, I appealed to his courtesy and feeling at once, but finding everything was against me, my passport, not needed by Englishmen in France, came into my thoughts, and showing the approval of several ambassadors for more than twenty consecutive years, for me to visit their lands, the Prefect made a polite bow, said he was sorry and hoped I would lunch with him the next day. I did so, but the lunch did not take away the rheumatism I contracted from turning out in the cold night.

The Rev. Chairman in moving a vote of thanks to the lecturer, observed, that from personal travel in which his friend Dr. Phené had joined him for a number of years he could vouch for many matters of deep scientific interest they had come against. The opinions expressed were of course the personal opinions of the lecturer, upon which all would form their own judgment. The lecture showed great observation and thought. He had not himself been to Brittany, but he had found much to interest him in the antiquities of the Channel Islands, and was sure that pursuits of this sort gave much zest to travel. The chairman then described in a very interesting manner, and from his own personal experiences, the "danse ronde" at Helstone, in Cornwall, and the orientation of some of the monuments in the Channel Islands.