Robbins Library Digital Projects Announcement: We are currently working on a large-scale migration of the Robbins Library Digital Projects to a new platform. This migration affects The Camelot Project, The Robin Hood Project, The Crusades Project, The Cinderella Bibliography, and Visualizing Chaucer.

While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

Malory's Morte d'Arthur: Exhibition Guide

Image from Lancelot Speed's "'This girdle, lords,' said she, 'is made for the most part of mine own hair, which, while I was yet in the world, I loved most well'"

Note: This is an online version of a pamphlet created by Kara L. McShane for a Rossell Hope Robbins Library exhibition.

The exhibit ran from January to May of 2010.

Images of the exhibition may be found here.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Notable Early Editions of Malory

- Illustrated and Children's Editions

- Fine Art

- Select Bibliography

Introduction

Most Arthurian tales popularly circulated in the English-speaking world are to some extent drawn from Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur. Dating from the fifteenth century, Malory's work tells the story of the legendary King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, starting from Arthur's birth until his tragic death. Scholars Elizabeth Archibald and A. S. G. Edwards have observed that "for over five hundred years, [Malory's Morte d'Arthur] has retained an appeal that, with the exception of Chaucer's works, no other work of medieval English literature has sustained" (xiii). Malory's romance draws heavily from French sources such as the French Lancelot-Grail (or Vulgate) Cycle and the Prose Tristan as well as Middle English sources such as the Alliterative Morte Arthure and the Stanzaic Morte Arthur. Malory's account of Arthur and his court captures popular audiences, and his text has been interpreted and reinterpreted by generations of writers, artists, and critics.

Most Arthurian tales popularly circulated in the English-speaking world are to some extent drawn from Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur. Dating from the fifteenth century, Malory's work tells the story of the legendary King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, starting from Arthur's birth until his tragic death. Scholars Elizabeth Archibald and A. S. G. Edwards have observed that "for over five hundred years, [Malory's Morte d'Arthur] has retained an appeal that, with the exception of Chaucer's works, no other work of medieval English literature has sustained" (xiii). Malory's romance draws heavily from French sources such as the French Lancelot-Grail (or Vulgate) Cycle and the Prose Tristan as well as Middle English sources such as the Alliterative Morte Arthure and the Stanzaic Morte Arthur. Malory's account of Arthur and his court captures popular audiences, and his text has been interpreted and reinterpreted by generations of writers, artists, and critics.Though little is known about Malory himself, the influence of his work has been considerable. Writers such as Alfred Tennyson, T. H. White, John Steinbeck, Mark Twain, and countless others have encountered the Arthurian world through some version of Malory's work and reinterpreted it in their own writing.

While Malory's romance has been vastly influential in England and America, it has reached readers in more than twenty other languages as well. Malory's Morte d'Arthur has been translated into Afrikaans, Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Welsh. The image at the left shows the cover of a Russian translation of Caxton's edition.

This exhibition celebrates the five hundred twenty-fifth anniversary of the original publication of Malory's influential work by William Caxton, England's first printer, in 1485. It is the first in a series of exhibitions at the Rossell Hope Robbins Library celebrating this milestone; the next exhibition will focus on Alfred Tennyson's Arthurian work. The items in this exhibition are from the collection of Alan Lupack and Barbara Tepa Lupack.

Notable Early Editions of Malory

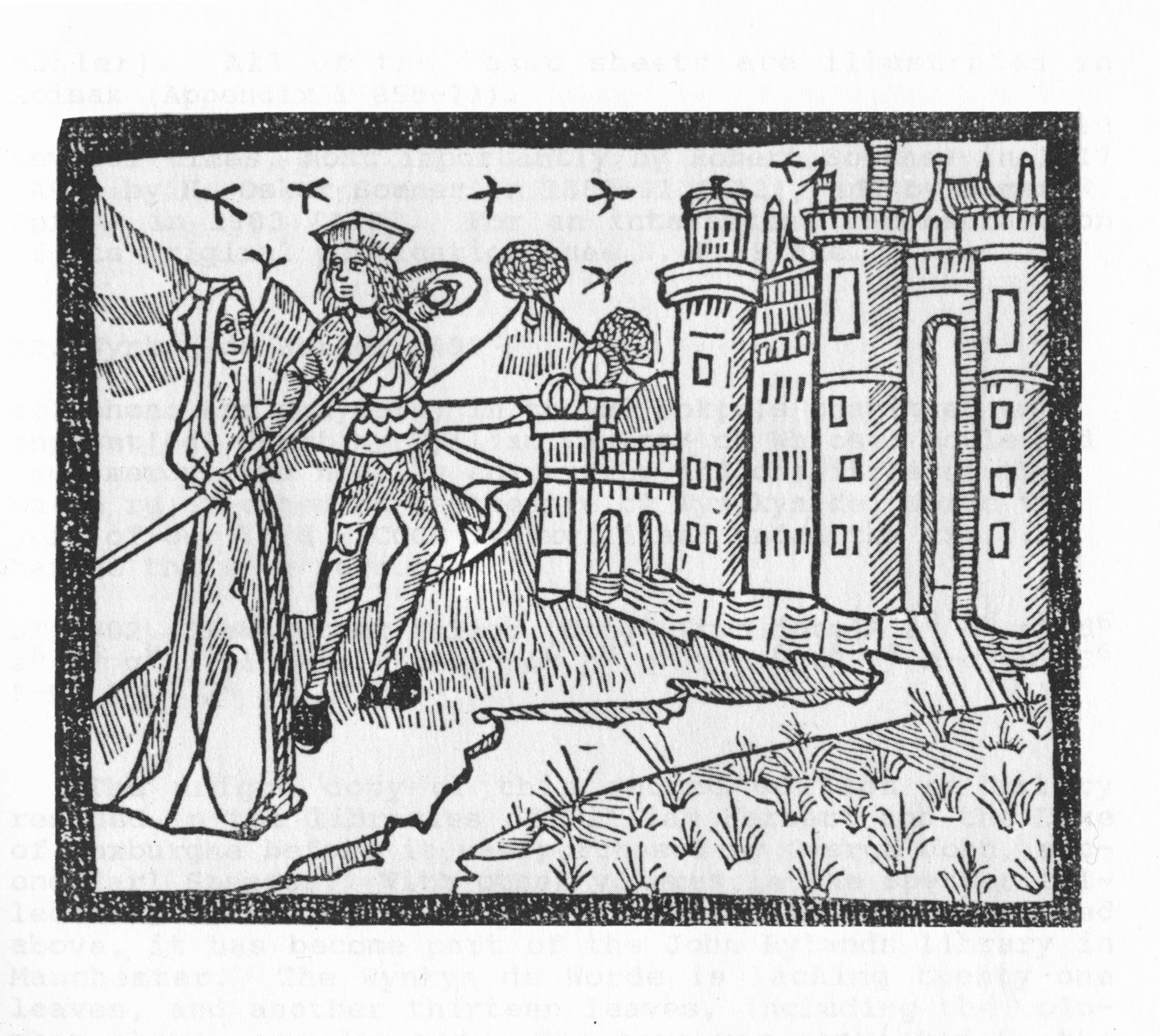

William Caxton's edition of Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur was the basis of all editions of Malory published before the 1934 discovery of the Winchester Manuscript, the only known extant medieval manuscript of the Morte d'Arthur. Caxton's 1485 Malory survives in only two copies, currently at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City and the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England. The facsimile of the Morgan copy in this exhibition was printed in 1976 by the Scolar Press in an edition of only 500 copies. Of these, 50 copies, numbered I through L, were printed on handmade paper. The copy featured in this exhibition is copy number XXX. Malory's Morte d'Arthur was printed five times between Caxton's first publication and the nineteenth century. Wynkyn de Worde published the first illustrated edition of Malory in 1498; it includes woodcuts prepared specifically for the edition by an unknown artist called simply "the Arthur cutter." The image at the right is a reproduction of one of these original woodcuts. While the illustrations were a new addition, de Worde made very few changes to Caxton's text. His edition survives in one copy, currently at the John Rylands Library. Though it is not a facsimile, this 1933 version of the 1498 edition reprints the original woodcuts and reproduces de Worde's text. The two-volume set was edited by A. S. Mott and published for the Shakespeare Head Press.

Malory's Morte d'Arthur was printed five times between Caxton's first publication and the nineteenth century. Wynkyn de Worde published the first illustrated edition of Malory in 1498; it includes woodcuts prepared specifically for the edition by an unknown artist called simply "the Arthur cutter." The image at the right is a reproduction of one of these original woodcuts. While the illustrations were a new addition, de Worde made very few changes to Caxton's text. His edition survives in one copy, currently at the John Rylands Library. Though it is not a facsimile, this 1933 version of the 1498 edition reprints the original woodcuts and reproduces de Worde's text. The two-volume set was edited by A. S. Mott and published for the Shakespeare Head Press.Wynkyn de Worde published another edition of Malory's work in 1529. This edition was followed by one printed by William Copland in 1557, one printed by Thomas East circa 1578, and another printed by William Stansby for Jacob Bloom in 1634. No editions were printed between 1634 and 1816 – a lapse of 182 years.

In 1816, two new editions of Malory appeared. The first, a two-volume edition, was edited by Alexander Chalmers with illustrations by Thomas Uwins. The text of this edition, known to John Keats, William Wordsworth, and Alfred Tennyson, is almost identical to that of the 1634 edition.

Tennyson also owned a copy of Joseph Haslewood's 1816 three-volume edition. Haslewood made more editorial changes than Chalmers, but as this edition was larger and more expensive, it did not sell as well as Chalmers's edition. The copy of this edition featured in the exhibition is still in its original boards, which is rare; most surviving copies have been rebound.

Robert Southey wrote the introduction and notes for an 1817 edition of Malory's work, and his name is most commonly associated with it, though it was edited by William Upcott. William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones knew Southey's edition, as did Algernon Charles Swinburne and Matthew Arnold. Barry Gaines identifies it as the authoritative version of Malory for half a century (19).

Robert Southey wrote the introduction and notes for an 1817 edition of Malory's work, and his name is most commonly associated with it, though it was edited by William Upcott. William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones knew Southey's edition, as did Algernon Charles Swinburne and Matthew Arnold. Barry Gaines identifies it as the authoritative version of Malory for half a century (19).In 1868, Sir Edward Strachey declared that his newly-published version of Malory was "an edition for ordinary readers, and especially for boys, from whom the chief demand for this book will always come" (qtd. in Gaines 21). His bowdlerized edition removed, among other things, Mordred's incestuous origin and Galahad's illegitimate one. Mark Twain likely owned Strachey's edition; Barry Gaines observes that "Twain's manuscript for A Connecticut Yankee instructs the typist to insert passages from Malory into four places in the book, and the page numbers correspond to those of the Globe Edition" (24). The image to the left shows the cover of the reprint of Strachey's 1868 edition.

In 1934, the Winchester Manuscript of Malory's work was discovered at Winchester College; it is the only known surviving manuscript of Malory's Morte, and it is likely that Caxton had it in his workshop (Life 10). Eugène Vinaver's edition of Malory, which uses the manuscript as its basis, was published in 1947. The discovery of the manuscript made it clear that Caxton was more than simply the first publisher of Malory's Morte d'Arthur; he was its first editor, responsible for changes to the content and the style of the work (Archibald and Edwards xiii). Though Vinaver's version has become the standard for scholars, editions based on Caxton's version are still being published. One recent edition of the Caxton Malory is the Cassell and Company's 2000 edition, which is the first complete edition illustrated entirely by a female artist. Anna-Marie Ferguson selects unusual moments and characters for her illustrations, which often feature Arthurian women. Her Arthurian tarot, called Legend, was published in 1995, and it was this work that led to her commission to illustrate the Cassell edition. An original painting by Ferguson that was reproduced as an illustration also appears in this exhibition.

Illustrated and Children's Editions

As more editions of Malory were published, these versions of the medieval text inspired reinterpretation by artists. Arthurian book illustration became a tradition in its own right. Illustrated editions were especially common in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and they continue to be popular through the present day. As Barbara Tepa Lupack has observed, "the contributions of Arthurian book illustrators from the mid-nineteenth-century Arthurian Revival to the present have been as remarkable as they have been varied" (10). (More illustrations, by the artists featured in this exhibition and many others, can be found at The Camelot Project at the University of Rochester, an online database of Arthurian texts, images, and basic information. ) Aubrey Beardsley began this tradition of modern Arthurian illustration. His illustrations accompanied a modernization of Caxton's text, published in monthly installments during late 1893 and 1894. Some of his illustrations look pre-Raphaelite, particularly those that helped him obtain the commission for the edition; others were highly controversial in their late nineteenth-century context. As Barbara Tepa Lupack has observed in Illustrating Camelot, "in creating such androgynous, effeminate, and otherwise atypical and unknightly knights, Beardsley deliberately blurred gender roles and challenged Victorian notions of sexuality" (82). An artist's proof of one of Beardsley's illustrations, depicting Merlin and Nimue, appears in this exhibition.

Aubrey Beardsley began this tradition of modern Arthurian illustration. His illustrations accompanied a modernization of Caxton's text, published in monthly installments during late 1893 and 1894. Some of his illustrations look pre-Raphaelite, particularly those that helped him obtain the commission for the edition; others were highly controversial in their late nineteenth-century context. As Barbara Tepa Lupack has observed in Illustrating Camelot, "in creating such androgynous, effeminate, and otherwise atypical and unknightly knights, Beardsley deliberately blurred gender roles and challenged Victorian notions of sexuality" (82). An artist's proof of one of Beardsley's illustrations, depicting Merlin and Nimue, appears in this exhibition.Arthur Rackham's well-known illustrations appeared in 1917, in an abridgment of Malory by Alfred W. Pollard. Rackham's work is particularly notable for his depiction of animals, including Tristram's brachet, the dragon Lancelot slays, and the mysterious Questing Beast. His illustrations have been said to be "among the most memorable and evocative images of the Arthurian world" (Lupack, Illustrating Camelot 164). The illustration shown, "How Mordred was slain by Arthur," captures the stark reality of war, a theme particularly appropriate to a piece created during World War I. Rough lines and a lack of color depict a dark landscape as Arthur and Mordred fight among the wreckage of the great battle. This lack of color is particularly noticeable because color plays such a role in Rackham's art; his illustration of the Questing Beast, for example, shows the fantastic creature blending into the blues and browns of the landscape surrounding it.

Pollard's complete edition of Malory had been published several years earlier, in 1910-11, with watercolor illustrations by Sir William Russell Flint. Flint produced forty-eight watercolors for this four-volume edition over the course of these two years; in 1920, a two-volume set containing thirty-six plates was published. Flint's work is particularly interesting because his illustrations adhere fairly closely to Malory's text; he illustrates most of the major events in the work for the four-volume edition (Lupack, Illustrating Camelot 114). An original watercolor by Flint appears in this exhibition.

H. J. Ford's illustrations accompanied Andrew Lang's 1902 Arthurian tales in The Book of Romance. Lang, like storyteller and illustrator Howard Pyle, claims to have based his Arthurian material on Malory. Like fellow illustrator Lancelot Speed, Ford also provided illustrations for Lang's well-known collections of fairy stories. The image at right, "Arthur and Guinevere Kiss Before All The People," appears in Lang's book.

H. J. Ford's illustrations accompanied Andrew Lang's 1902 Arthurian tales in The Book of Romance. Lang, like storyteller and illustrator Howard Pyle, claims to have based his Arthurian material on Malory. Like fellow illustrator Lancelot Speed, Ford also provided illustrations for Lang's well-known collections of fairy stories. The image at right, "Arthur and Guinevere Kiss Before All The People," appears in Lang's book.Arthur Dixon's first illustrated version of tales based on Malory's Morte d'Arthur, from 1920, featured only six color plates; the following year, he illustrated another version, edited by Doris Ashley, which included twelve plates. An original painting by Dixon appears in this exhibition; the volume featured in the exhibition is from 1920, edited by John Lea.

James Knowles's adaptation of Malory's text was first published in 1862, though his name did not appear on the title page of the work until its eighth edition in 1895. Like many other Victorian editors, Knowles abridged the text in order to make it more palatable to contemporary readers. The first edition was dedicated to Alfred Tennyson, whose first four Idylls had been published when Knowles was preparing his abridgment. Knowles's version went through many printings, with illustrations by various artists. G. H. Thomas was the illustrator of the first edition; Louis Rhead's illustrations appear in the edition in this exhibition. In the illustration shown, Rhead depicts the Questing Beast, a mysterious creature traditionally described as an amalgamation of a snake, a deer, a hare, and a leopard. Rhead's version departs from this description. Lancelot Speed's illustrations first appeared in the ninth edition of Knowles's adaptation, published in 1912.

The aptly-named Lancelot Speed also illustrated Rupert S. Holland's King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, published in 1919. Holland's version uses Knowles's text as its basis but adds some material from Chrétien de Troyes's twelfth-century poem Perceval. Speed's depiction of Galahad receiving a sword-belt from Perceval's sister demonstrates Galahad's nobility in his upright stance. Speed had no formal art training, yet he became a successful illustrator, known for his Arthurian illustrations as well as his illustrations for Andrew Lang's Fairy Books.

Mary MacLeod's 1900 children's version of Malory was first published with illustrations by A. G. Walker. MacLeod's adaptation was commonly used in schools, and portions of the text have been reprinted in various editions. For example, extracts were published by Wells Gardner, Darton and Company in a weekly magazine for children from 1901 to 1906.

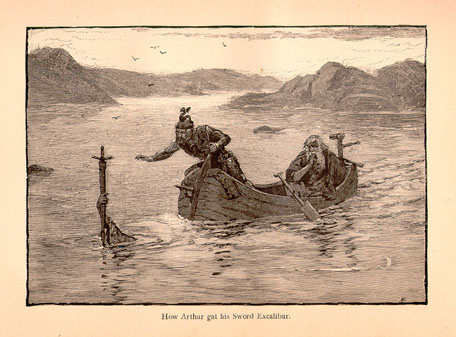

Sidney Lanier's The Boy's King Arthur was a common introduction to Arthurian material for several generations. First published in 1880, it was one of the earliest adaptations for children, and it became one of the most enduring. Lanier's adaptation was especially popular with Arthurian youth groups such as the Knights of King Arthur and the Knighthood of Youth. Thousands of American children participated in these groups, which Alan Lupack and Barbara Tepa Lupack have described as "modeled on the ideals of chivalry and a bowdlerized reading of the Arthurian tales" (Lupack, King Arthur in America xii). The 1880 edition of Lanier's work included in the exhibition features black-and-white illustrations by Alfred Kappes. The image by Kappes featured in the exhibition depicts Arthur receiving Excalibur, a moment particularly popular with illustrators.

The 1917 reissue of Lanier's work replaced Kappes's work with color illustrations by N. C. Wyeth. Though Wyeth also depicts Arthur receiving Excalibur, the image itself is drastically different. Merlin is in the same position in both images, slightly behind Arthur. However, in Kappes's work, Arthur carefully reaches out for the sword, while Wyeth's Arthur stands upright with his arms crossed. The change suggests a different perspective on Arthur; while Kappes's Arthur actively claims his destiny, the Arthur in Wyeth's interpretation stands confidently, waiting to reach it.

The 1917 reissue of Lanier's work replaced Kappes's work with color illustrations by N. C. Wyeth. Though Wyeth also depicts Arthur receiving Excalibur, the image itself is drastically different. Merlin is in the same position in both images, slightly behind Arthur. However, in Kappes's work, Arthur carefully reaches out for the sword, while Wyeth's Arthur stands upright with his arms crossed. The change suggests a different perspective on Arthur; while Kappes's Arthur actively claims his destiny, the Arthur in Wyeth's interpretation stands confidently, waiting to reach it.Wyeth was a student of Howard Pyle, the most important book illustrator of the day. Pyle's four illustrated Arthurian books are not editions of Malory's text; rather, they retell selected stories with particular emphasis on the noble behavior of the knights featured (Lupack, Illustrating Camelot 190). The texts as well as the illustrations were very popular, and all of them were published in several editions (Gaines 85). Pyle's Arthurian work influenced not only Wyeth but also a number of Pyle's other students, including Stanley M. Arthurs and Frank E. Schoonover.

The tradition of book illustration passed from N. C. Wyeth to his son, Andrew Wyeth, who illustrated John W. Donaldson's Arthur Pendragon of Britain. Andrew Wyeth provided four character portraits for Donaldson's 1943 work, which is based on A. J. Pollard's 1910-11 edition of Malory. The image featured in the exhibition depicts Merlin advising a resolute Arthur. This image, like the others Wyeth contributed to the book, depicts only the characters rather than any particular scene.

Henry Gilbert's children's adaptation, King Arthur's Knights, first appeared in 1911 with sixteen illustrations by Walter Crane. Crane's first Arthurian project was a series of illustrations for Tennyson's "The Lady of Shallot" done early in his career; Crane's illustrations for Gilbert's adaptation were the last ones he completed before his death, and they have been called "highpoints in the development of popular Arthurian book illustration" (Lupack 151). The illustration shown in the exhibition depicts Lancelot preventing Bors from killing Arthur. Though at this point in Malory's text the two are engaged in battle, Lancelot is still loyal and noble enough that he refuses to let Arthur be slain. Gilbert's popular text was reprinted many times (with various abridgments) between 1911 and 1940. These versions featured illustrations not only by Crane but also by Frances Brundage and T. H. Robinson.

Fine Art

Aubrey Beardsley, "Merlin and Nimue." [Artist's Proof.]

Aubrey Beardsley, "Merlin and Nimue." [Artist's Proof.]This artist's proof would have been shown to Beardsley for approval before his illustrated edition of Malory was printed. In different versions of the legend, Merlin is sealed in either a tree or a cave by Nimue (who is alternately called Vivien and Nineve). Beardsley's rendition shows her in the upper left, peering at him while he approaches the cave that will be his tomb. Merlin's clothing blends into the rock behind him, foreshadowing his impending fate. The image demonstrates Beardsley's androgynous figures; both characters wear flowing garments and have long hair.

Sir William Russell Flint, "'Lo!' said Merlin, 'yonder is that sword that I spake of.'

With that they saw a damosel going upon the lake." [Original Watercolor.]

The scene where Arthur receives Excalibur is very commonly illustrated, but artists' interpretations of it vary drastically. Flint's illustration is particularly interesting because it shows the lady on the water, while other versions tend to show only the protruding hand clutching the sword. Her dress parallels the swirling motion of the water, demonstrating Flint's masterful use of his medium. (For other examples of Arthur receiving Excalibur, see N. C. Wyeth's and Alfred Kappes's versions, included in this exhibition.)

H. J. Ford, "Arthur and Guinevere Kiss Before All the People." (1902) [Original Drawing.]

Ford's illustrations for The Book of Romance also accompanied two other versions of Andrew Lang's text. They appeared in Tales of the Round Table in 1903 and Tales of King Arthur and the Round Table in 1905. Ford's illustrations were very popular; in fact, when his illustrations were replaced by those of Charles Mozley for a large-print edition of Lang's text, Mozley based his illustrations on Ford's art (Gaines 90). Ford's illustrations are notable for their detail. For example, in the original drawing in this exhibition, Arthur's clothing features intricate patterns, and mounted knights are visible in the background.

Arthur Dixon, "The Knighting of Sir Galahad." [Original Watercolor.]

Dixon's watercolor shows Arthur knighting the young Sir Galahad; this depiction is particularly interesting because, in Malory's text, Lancelot knights Galahad in a chapel in the woods. However, the depiction of Galahad himself is typical of art of this time; he is generally portrayed as young and pure, and he was seen as a role model for young men.

Beatrice Clay, Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table. Ill. Dora Curtis. London: J. M. Dent, [1905].

Beatrice Clay, Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table. Ill. Dora Curtis. London: J. M. Dent, [1905].Dora Curtis, Dust Jacket/Cover Art for Beatrice Clay's Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table.

Dora Curtis, "Morgan le Fay." [Frontispiece for Beatrice Clay's Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table.]

Beatrice Clay's edition, first titled Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table, was designed for young audiences. This initial version was adapted multiple times with changes in illustrations and additions to the text between its first appearance in 1901 and 1936. Dora Curtis's color illustrations first appeared in 1905. Clay's first edition of the text removed Morgan le Fay; however, in 1905, she wrote that "Arthurian stories which had nothing to tell about this great sorceress were somewhat in the case of a 'Hamlet' without the Ghost" (qtd. in Gaines 89). Clay's new vision of the text featured Morgan in a much more central role; she is so central that Curtis's frontispiece for the edition depicts her. In the original watercolor featured in the exhibition, Morgan looks exotic, complete with a parrot and a Moor in the upper corners of the watercolor.

In this exhibition, Curtis's original artwork for the spine and cover appears next to the edition. The cover features a knight before an angel with a cup, an image commonly associated with the quest for the Holy Grail.

Anna-Marie Ferguson, "The Four Queens." [Original Watercolor.]

Ferguson illustrates Lancelot's capture by Morgan le Fay, the Queen of Northgalis, the Queen of Eastland, and the Queen of the Out Isles. When the four queens find Lancelot under a tree, Morgan le Fay places him under an enchantment and brings him to her castle, where they demand that he choose which of them he would have for his lover. However, Lancelot would not have any of them because of his devotion to Guinevere. He is rescued by a damsel and agrees to fight on behalf of her father, King Bagdemagus, in exchange.

John Howe, "The Slaying of the Adder." [Original Watercolor from Time-Life Series: The Enchanted World. The Fall of Camelot.]

The slaying of the adder depicted by Howe appears near the end of Malory's Morte. At this point in the text, the war between Arthur and Mordred has begun; they meet to negotiate a peace arrangement. However, Arthur warns his knights to slay Mordred if they see a sword drawn. When a nameless knight is stung by an adder, he draws his sword to slay it, and the battle begins. In the final battle, Arthur and Mordred kill each other.

Bibliography

Notable Editions of Caxton's Malory

Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte D'Arthur Printed by William Caxton 1485: Reproduced in Facsimile from the Copy in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, with an Introduction by Paul Needham. London: The Scolar Press in association with the Pierpont Morgan Library, 1976. Of the edition of five hundred copies, fifty, numbered I to L, have been printed on paper specially made by hand by Barcham Green of Hayle Mill. This is copy number XXX. The binding is by the Eddington Bindery, Hungerford, Berkshire.

Malory, Sir Thomas. The Noble & Joyous Boke Entytled Le Morte Darthur Notwythstondyng It Treateth of the Byrth Lyf and Actes of the Sayd Kynge Arthur: Of His Noble Knyghtes of the Rounde Table, Theyr Merveyllous Enquestes and Adventures Thachyevyng of the Sanc-Greall and in the Ende the Dolourous Deth: And Departynge out of This Worlde of Them Al. 2 vols. Oxford: Shakespeare Head Press, 1933. No. 72 of 370 copies from the unique copy of the edition printed by Wynkyn de Worde at Westminster in 1498, now in the John Rylands Library at Manchester.

Malory, Sir Thomas. The History of the Renowned Prince Arthur, King of Britain; with His Life and Death, and All His Glorious Battles. Likewise, the Noble Acts and Heroic Deeds of His Valiant Knights of the Round Table. 2 vols. London: Walker and Edwards, 1816. [Ed. Alexander Chalmers.]

Malory, Sir Thomas. La Mort D'Arthur: The Most Ancient and Famous History of the Renowned Prince Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. 3 vols. London: R. Wilks, 1816. [Ed. Joseph Haselwood.] In original boards.

Malory, Sir Thomas. The Byrth, Lyf, and Actes of Kyng Arthur; of His Noble Knyghtes of the Rounde Table, Theyr Merveyllous Enquests and Aduentures, Thachyeuyng of the Sanc Greal; and in the End le Morte Darthur, with the Dolorous Deth and Departyng Out of Thys Worlde of Them Al. [Ed. William Upcott.] With an Introduction and Notes by Robert Southey. London: for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown by Thomas Davidson, 1817. Bound in full red crushed morocco by Riviere & Son. One of 50 large paper copies.

Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte Darthur: Sir Thomas Malory's Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table: The Text of Caxton. Ed., with an introd. by Sir Edward Strachey. London: Macmillan, 1906. [Strachey's edition was first printed in 1868.]

Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte d'Arthur. Ed. John Matthews. Ill. Anna-Marie Ferguson. London: Cassell, 2000.

Illustrated and Children's Editions

Ashley, Doris. King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Ill. Arthur A. Dixon. Ed. Capt. E. Vredenburg. London: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n.d.

Clay, Beatrice. Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table. Ill. Dora Curtis. London: J. M. Dent, [1905].

Donaldson, John W., ed. Arthur Pendragon of Britain: A Romantic Narrative by Sir Thomas Malory. Ill. Andrew Wyeth. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1943.

Gilbert, Henry. King Arthur's Knights: The Tales Re-Told for Boys & Girls. With 16 illustrations in colour by Walter Crane. Ill. Walter Crane. Edinburgh & London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, [1911].

Holland, Rupert S., ed. King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Ill. Lancelot Speed. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs and Co., 1919.

Knowles, Sir James, comp. King Arthur and His Knights. Ill. Louis Rhead. New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1923.

Lanier, Sidney. The Boy's King Arthur: Being Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table. Edited with an introduction by Sidney Lanier. Ill. Alfred Kappes. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1880.

-----. The Boy's King Arthur: Being Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table. Ill. N. C. Wyeth. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1917.

Lang, Andrew. The Book of Romance. Ill. H. J. Ford. New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1902.

MacLeod, Mary. King Arthur and His Noble Knights: Stories from Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur. Intro. John H. Hales. Ill. A. G. Walker. New York: A. L. Burt Co., n.d.

Malory, Thomas. The Birth, Life and Acts of King Arthur: of His Noble Knights of the Round Table, Their Marvellous Enquests and Adventures, The Achieving of the San Greal, and in the End le Morte d'Arthur, with the Dolorous Death and Departing out of This World of Them All. The Text as Written by Sir Thomas Malory and Imprinted by William Caxton at Westminster the Year MCCCCLXXXV and Now Spelled in Modern Style. With an intro. by Prof. John Rhys and a note on Aubrey Beardsley by Aymer Vallance. Ill. Aubrey Beardsley. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1927.

Malory, Thomas. Le Morte Darthur: The History of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table. Ill. Russell Flint. 2 vols. London: Philip Lee Warner (Publisher to the Medici Society), 1920.

Pollard, Alfred W., abridger. The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table. Abridged from Malory's Morte d'Arthur. Ill. Arthur Rackham. London: Macmillan, 1917. 1 of 500 copies signed by the illustrator.

Original Art

Beardsley, Aubrey. "Merlin and Nimue." Artist's Proof.

Curtis, Dora. Dust Jacket/Cover Art for Beatrice Clay's Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table. Original Watercolor.

-----. "Morgan le Fay." Original Watercolor.

Dixon, Arthur. "The Knighting of Sir Galahad." Original Watercolor.

Ferguson, Anna-Marie. "The Four Queens." Original Watercolor.

Flint, William Russell. "'Lo!' said Merlin, 'yonder is that sword that I spake of.' With that they saw a damosel going upon the lake." Original Watercolor.

Ford, H. J. "Arthur and Guinevere Kiss Before All the People." Original Drawing.

Howe, John. "The Slaying of the Adder." From Time-Life Series: The Enchanted World. The Fall of Camelot. Original Watercolor.

Resources

Archibald, Elizabeth, and A. S. G. Edwards, eds. A Companion to Malory. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1996.

Gaines, Barry. Sir Thomas Malory: An Anecdotal Bibliography of Editions, 1485-1985. New York: AMS Press, 1990.

Life, Page West. Sir Thomas Malory and the Morte Darthur: A Survey of Scholarship and Annotated Bibliography. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1980.

Lupack, Alan, and Barbara Tepa Lupack. King Arthur in America. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 1999.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa, with Alan Lupack. Illustrating Camelot. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 2008.

Bibliography

Notable Editions of Caxton's Malory

Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte D'Arthur Printed by William Caxton 1485: Reproduced in Facsimile from the Copy in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, with an Introduction by Paul Needham. London: The Scolar Press in association with the Pierpont Morgan Library, 1976. Of the edition of five hundred copies, fifty, numbered I to L, have been printed on paper specially made by hand by Barcham Green of Hayle Mill. This is copy number XXX. The binding is by the Eddington Bindery, Hungerford, Berkshire.

Malory, Sir Thomas. The Noble & Joyous Boke Entytled Le Morte Darthur Notwythstondyng It Treateth of the Byrth Lyf and Actes of the Sayd Kynge Arthur: Of His Noble Knyghtes of the Rounde Table, Theyr Merveyllous Enquestes and Adventures Thachyevyng of the Sanc-Greall and in the Ende the Dolourous Deth: And Departynge out of This Worlde of Them Al. 2 vols. Oxford: Shakespeare Head Press, 1933. No. 72 of 370 copies from the unique copy of the edition printed by Wynkyn de Worde at Westminster in 1498, now in the John Rylands Library at Manchester.

Malory, Sir Thomas. The History of the Renowned Prince Arthur, King of Britain; with His Life and Death, and All His Glorious Battles. Likewise, the Noble Acts and Heroic Deeds of His Valiant Knights of the Round Table. 2 vols. London: Walker and Edwards, 1816. [Ed. Alexander Chalmers.]

Malory, Sir Thomas. La Mort D'Arthur: The Most Ancient and Famous History of the Renowned Prince Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. 3 vols. London: R. Wilks, 1816. [Ed. Joseph Haselwood.] In original boards.

Malory, Sir Thomas. The Byrth, Lyf, and Actes of Kyng Arthur; of His Noble Knyghtes of the Rounde Table, Theyr Merveyllous Enquests and Aduentures, Thachyeuyng of the Sanc Greal; and in the End le Morte Darthur, with the Dolorous Deth and Departyng Out of Thys Worlde of Them Al. [Ed. William Upcott.] With an Introduction and Notes by Robert Southey. London: for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown by Thomas Davidson, 1817. Bound in full red crushed morocco by Riviere & Son. One of 50 large paper copies.

Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte Darthur: Sir Thomas Malory's Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table: The Text of Caxton. Ed., with an introd. by Sir Edward Strachey. London: Macmillan, 1906. [Strachey's edition was first printed in 1868.]

Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte d'Arthur. Ed. John Matthews. Ill. Anna-Marie Ferguson. London: Cassell, 2000.

Illustrated and Children's Editions

Ashley, Doris. King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Ill. Arthur A. Dixon. Ed. Capt. E. Vredenburg. London: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n.d.

Clay, Beatrice. Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table. Ill. Dora Curtis. London: J. M. Dent, [1905].

Donaldson, John W., ed. Arthur Pendragon of Britain: A Romantic Narrative by Sir Thomas Malory. Ill. Andrew Wyeth. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1943.

Gilbert, Henry. King Arthur's Knights: The Tales Re-Told for Boys & Girls. With 16 illustrations in colour by Walter Crane. Ill. Walter Crane. Edinburgh & London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, [1911].

Holland, Rupert S., ed. King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Ill. Lancelot Speed. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs and Co., 1919.

Knowles, Sir James, comp. King Arthur and His Knights. Ill. Louis Rhead. New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1923.

Lanier, Sidney. The Boy's King Arthur: Being Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table. Edited with an introduction by Sidney Lanier. Ill. Alfred Kappes. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1880.

-----. The Boy's King Arthur: Being Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table. Ill. N. C. Wyeth. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1917.

Lang, Andrew. The Book of Romance. Ill. H. J. Ford. New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1902.

MacLeod, Mary. King Arthur and His Noble Knights: Stories from Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur. Intro. John H. Hales. Ill. A. G. Walker. New York: A. L. Burt Co., n.d.

Malory, Thomas. The Birth, Life and Acts of King Arthur: of His Noble Knights of the Round Table, Their Marvellous Enquests and Adventures, The Achieving of the San Greal, and in the End le Morte d'Arthur, with the Dolorous Death and Departing out of This World of Them All. The Text as Written by Sir Thomas Malory and Imprinted by William Caxton at Westminster the Year MCCCCLXXXV and Now Spelled in Modern Style. With an intro. by Prof. John Rhys and a note on Aubrey Beardsley by Aymer Vallance. Ill. Aubrey Beardsley. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1927.

Malory, Thomas. Le Morte Darthur: The History of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table. Ill. Russell Flint. 2 vols. London: Philip Lee Warner (Publisher to the Medici Society), 1920.

Pollard, Alfred W., abridger. The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table. Abridged from Malory's Morte d'Arthur. Ill. Arthur Rackham. London: Macmillan, 1917. 1 of 500 copies signed by the illustrator.

Original Art

Beardsley, Aubrey. "Merlin and Nimue." Artist's Proof.

Curtis, Dora. Dust Jacket/Cover Art for Beatrice Clay's Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table. Original Watercolor.

-----. "Morgan le Fay." Original Watercolor.

Dixon, Arthur. "The Knighting of Sir Galahad." Original Watercolor.

Ferguson, Anna-Marie. "The Four Queens." Original Watercolor.

Flint, William Russell. "'Lo!' said Merlin, 'yonder is that sword that I spake of.' With that they saw a damosel going upon the lake." Original Watercolor.

Ford, H. J. "Arthur and Guinevere Kiss Before All the People." Original Drawing.

Howe, John. "The Slaying of the Adder." From Time-Life Series: The Enchanted World. The Fall of Camelot. Original Watercolor.

Resources

Archibald, Elizabeth, and A. S. G. Edwards, eds. A Companion to Malory. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1996.

Gaines, Barry. Sir Thomas Malory: An Anecdotal Bibliography of Editions, 1485-1985. New York: AMS Press, 1990.

Life, Page West. Sir Thomas Malory and the Morte Darthur: A Survey of Scholarship and Annotated Bibliography. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1980.

Lupack, Alan, and Barbara Tepa Lupack. King Arthur in America. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 1999.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa, with Alan Lupack. Illustrating Camelot. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 2008.