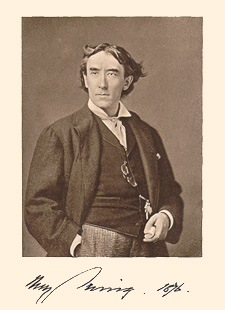

Henry Irving

The beginning of Brodribb's theatrical career came through an elocution class which was taught by Mr. and Mrs. Henry Thomas, where the focus of the acting exercises was to pull actors away from the current "rant" style, and into a much more subdued naturalistic form of acting. The program gave Brodribb, who had pretty much conquered his stammer, his first chance on stage, where, among other things, he had a successful turn in the role of Captain Jack Absolute in Sheridan's Rivals. The critics congratulated him for "displaying intelligent tact," and soon he had left the amateur theater and was starting to look for work elsewhere. Brodribb had befriended a man named William Hoskins, who was an actor in Samuel Phelps' company and, after a few weeks of personal work with Hoskins, was able to meet Phelps for the first time. Upon the meeting, Brodribb presented Phelps with a speech from Othello, to which Phelps responded, "Have nothing to do with the theater." To this rejection, Brodribb replied, "Well, sir, it seems strange that such advice should come from you, seeing that you enjoy so great a reputation as an actor. I think I shall take my chance and go upon the stage." His confidence and determination won over Phelps in the end, who offered Brodribb two pounds a week at Salder's Wells the next season (Bingham, 28).

Though Brodribb did not accept the invitation from Phelps, by 1856 he had moved to Sunderland, changed his name to Henry Irving, and looked to begin his professional career. He chose the name "Irving" from his beloved American writer Washington Irving, and kept his original middle name, Henry. At Sunderland, the theater company would have its actors prepare supporting roles for many different shows, then invite big name actors to play the leads for a short run. Though this initial experience was a lot of hard work with very little reward, Irving was able to share the stage at a very early age with some of the greatest actors of his day. After his first month of acting (for which he received no pay) Irving was taken on as an apprentice for the company and earned a small salary of about twenty five shillings. After about four months of his apprenticeship he was offered a position in Edinburgh, and it was here that his acting career truly took off. In the next two and a half years it is estimated that Irving learned between 350 and 400 parts, including memorable performances in El Hyder (Chief of the Ghant Mountains), Black-eyed Susan, The Lady of Lyons, Cramond Brig, Bride of Lammermoor, Dickens's Christmas Carol, Othello, Henry VIII, Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet and The Taming of the Shrew (Bingham, 38). Though during his time in Edinburgh he received his share of criticism from the papers, which critiqued his walk, his speech, and his portrayal of various roles, when he finally decided to leave Scotland in September of 1859, the critics rightfully sang his praises: "Mr. Irving is one of the most rising actors among us, and it is with regret that we part with him" (Bingham, 39).

The first person that Irving approached about a play about King Arthur was his friend, Sir Alfred Lord Tennyson, who had written the most powerful Arthurian narrative of the modern day: The Idylls of the King. Though Irving and the Lyceum had produced two of Tennyson's dramas already, the author refused to let them put the Idylls on stage. As Stoker put it, "He had dealt with the subject in one way and did not wish to try it in another" (Stoker, 253). Irving then approached the playwright W. G. Wills in 1890, but found the script he created unappealing. Finally, Irving found Joseph Comyns Carr, who finished a script he approved in 1893. Carr's adaptation of the Arthurian legend pulls a lot of its plot structure from both Malory and Tennyson, though it sticks to neither faithfully. Irving saw this play not only as a personal pursuit, but as a nationalistic emblem that he could give England. With this mindset, Irving spared no expense in putting the production together; he hired Sir Arthur Sullivan to compose the score, Sir Edward Burne-Jones to design the sets and costumes, and the two strong personalities of Ellen Terry in the role of Guinevere and Johnston Forbes-Robertson in the role of Lancelot. Lena Ashwell, who played Elaine, said that she loved to spend the majority of the third act on stage (as a dead corpse) so that she could feel the energy and hear the speeches delivered by Irving. She says of Irving, "He always called himself the 'servant of the public' and as the servant of the public there was no subservience but leadership. To him his art was a religion" (qtd. in Saintsbury, 329).

King Arthur opened on January 12, 1895 and ran for an entire season at the Lyceum (105 performances). The show went on to tour the United States and did seventy-four successful performances there to rave reviews. The show might have had run much longer, but, as Stoker remembers it in his Personal Reminiscences, "It was one of those plays cut short in its prime. The scenery and appointments were burned in the stage fire of 1898" (Stoker, 255).

His devotion to the English stage was recognized on every level of society, though when it came to the idea of Knighthood, Irving often shrugged it off: "[The actor] acts among his colleagues, without whom he is powerless; and to give him some distinction in the playbill which others could not enjoy would be prejudicial to his success--and fatal, I believe, to his popularity" (Goodman, 310). By the time that King Arthur took to the stage though, Irving decided to rethink the idea. Whether this was due to the success of his play, or the simple fact that he shared the playbill with two other "knights" (Burne-Jones and Sullivan), no one is really sure. But for whatever reasons, on May 24, 1895, Irving received a letter telling him that Queen Victoria had honored him with a knighthood "in personal recognition and for his services to art." Irving accepted the honor, and the next morning became the first actor ever knighted.

In October of 1905, Irving took to the stage for the last time in the role of Becket. His last line on stage was appropriately, "Into thy hands, oh Lord, into thy hands" (Bingham, 299). Irving died that evening in his hotel. Having touched many through his acting and even more through his reputation, Henry Irving was one of the most influential actors who ever reached the English stage. Upon reflection on his career, Lena Ashwell, who admits that she did not realize the greatness of Irving until after he had died, said, "There were giants in those days, and the giant who made the deepest and most lasting impression upon England was Henry Irving" (qtd. in Saintsbury, 351).

Bibliography

Bingham, Madeleine. Henry Irving and the Victorian Theater. Boston: George Allen and Unwin, 1978.

Goodman, Jonathan. "First Knight of the Stage." Contemporary Review 266 (June, 1995): 310-312.

Goodman, Jennifer R. "The Last of Avalon: Henry Irving's King Arthur of 1895." Harvard Library Bulletin 32.3 (Summer 1984): 239-255.

Saintsbury, H.A., and Cecil Palmer. We Saw Him Act. New York: Benjamin Blom, 1939.

Salter, Denis. "Henry Irving, the 'Dr. Freud' of Melodrama." In Melodrama. Ed. James Redmond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. 161-82.

Stoker, Bram. Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving. London: The MacMillan Company, 1906.

Bingham, Madeleine. Henry Irving and the Victorian Theater. Boston: George Allen and Unwin, 1978.

Goodman, Jonathan. "First Knight of the Stage." Contemporary Review 266 (June, 1995): 310-312.

Goodman, Jennifer R. "The Last of Avalon: Henry Irving's King Arthur of 1895." Harvard Library Bulletin 32.3 (Summer 1984): 239-255.

Saintsbury, H.A., and Cecil Palmer. We Saw Him Act. New York: Benjamin Blom, 1939.

Salter, Denis. "Henry Irving, the 'Dr. Freud' of Melodrama." In Melodrama. Ed. James Redmond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. 161-82.

Stoker, Bram. Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving. London: The MacMillan Company, 1906.