Moriaen, a black Christian knight from the Land of Moors and Percival’s nephew, appears in the Dutch Roman van Moriaen written in the 13th centaury. The unknown author provides a few metatextual claims such as that a scribe neglected this story when copying the Roman van Lanceloet and that another version exists where Moriaen was Percival’s son instead of his nephew (Moriaen 23-24). Unfortunately neither of the surviving copies of Moriaen, the complete copy found in the Lancelot-Compilatie and the Moriaen-fragment found by M. Steel, contain this version where Moriaen is Percival’s son; and some scholars speculate it may never have existed at all (Buuren 41, Reiss 224, 338, Wells, “Source” 40).

Moriaen, the result of a union between a black mother and a white father, seeks out his absent father in an attempt to restore his mother to her throne. Scholars have noted the similarity of this premise, a mixed race child searching for an absentee father, to Feirefiz the half-brother of Percival in Wolfram Von Eschenbach’s Parzival. This has resulted in scholarly debate as to the relationship between the two texts (Wells, “Source” 30-32).

In Moriaen, Moriaen enters the story by challenging Lancelot to a duel to win information about his father’s location, a duel that Gawain ends before there is a clear victor out of a growing respect for Moriaen’s prowess (Moriaen 434-448, 531-43). The three travel together until they come to a crossroad, after which, Moriaen struggles to gain supplies and aid from the locals who fear his skin and height (Moriaen 938-40, 1175-80, 2363-78, 2398-2410). He reunites with Gawain in time to save him from treachery and then, upon finding the information he needs, sets out with Gareth to his father’s location. Securing Gareth’s aid in taking a boat he could not

...

Read More

Read Less

Moriaen, a black Christian knight from the Land of Moors and Percival’s nephew, appears in the Dutch Roman van Moriaen written in the 13th centaury. The unknown author provides a few metatextual claims such as that a scribe neglected this story when copying the Roman van Lanceloet and that another version exists where Moriaen was Percival’s son instead of his nephew (Moriaen 23-24). Unfortunately neither of the surviving copies of Moriaen, the complete copy found in the Lancelot-Compilatie and the Moriaen-fragment found by M. Steel, contain this version where Moriaen is Percival’s son; and some scholars speculate it may never have existed at all (Buuren 41, Reiss 224, 338, Wells, “Source” 40).

Moriaen, the result of a union between a black mother and a white father, seeks out his absent father in an attempt to restore his mother to her throne. Scholars have noted the similarity of this premise, a mixed race child searching for an absentee father, to Feirefiz the half-brother of Percival in Wolfram Von Eschenbach’s Parzival. This has resulted in scholarly debate as to the relationship between the two texts (Wells, “Source” 30-32).

In Moriaen, Moriaen enters the story by challenging Lancelot to a duel to win information about his father’s location, a duel that Gawain ends before there is a clear victor out of a growing respect for Moriaen’s prowess (Moriaen 434-448, 531-43). The three travel together until they come to a crossroad, after which, Moriaen struggles to gain supplies and aid from the locals who fear his skin and height (Moriaen 938-40, 1175-80, 2363-78, 2398-2410). He reunites with Gawain in time to save him from treachery and then, upon finding the information he needs, sets out with Gareth to his father’s location. Securing Gareth’s aid in taking a boat he could not use before due to the owner’s fear of him (Moriaen 2477-2604, 2930-44, 3413-47, 3106-7). Upon reuniting with his father, he convinces him to return home with him, and while waiting for his father to heal enough to travel, he joins Gawain, Lancelot, and Percival in saving King Arthur from Irish invaders before returning home to his own kingdom and restoring legitimate rule (Moriaen 3584-659, 3918-60, 4163-560).

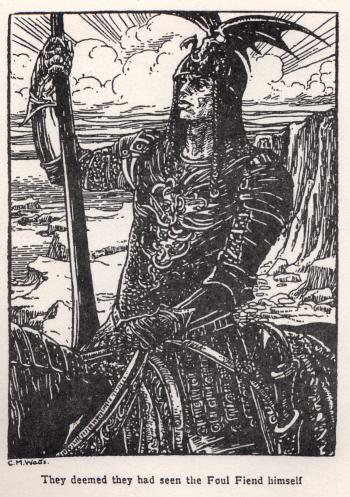

Throughout the text characters and the author refer to Moriaen’s blackness and height as his most defining features which often evoke fear in those who see him (confer, for example, Moriaen 422-24). Even knights such as Gawain (cf., for example, Moriaen 489-90) and Gareth react to it, but despite any initial shock, they are quick to accept Moriaen and treat him as an equal (Moriaen 489-90, 2934-6, 2938-44). This is perhaps in part because he, unlike Feirefiz, is Christian, a culture similarity he shares with them (Heng 200). Moriaen faces more difficulty dealing with other people, non-knights, who fear his appearance and flee from him before he can ask for lodgings or passage on a boat (Heng 207, Moriaen 3363-3447 Moriaen 3447, 3451, 3458). Even Gareth’s recommendation is not enough to dispel this fear of Moriaen. Despite the fear he provokes, Moriaen’s actions remain chivalrous and the text itself reaffirms that his blackness does not make him any less of a knight: “he was black what harm was it?” (Moriaen 771, Heng 202, Wells “The Middle” 250).

BibliographyBuuren, A.M.J. van. “Een Moriaen-fragment geïdentificeerd.” Nieuwe Taalgids vol. 67, 1974, p.41-46. (Available online.)

Heng, Geraldine. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Moriaen, trans. David Johnson and Geert Claassens (unpublished). The version used in this article was generously provided to me by Dr. Thomas Hahn. He in turn, received it directly from David Johnson and Geert Claassens who translated it from its original Dutch. Many thanks to all of them.

Reiss, Edmund. Arthurian Legend and Literature: an Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland. 1984.

Wells, D. A. “The Middle Dutch Moriaen, Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, and Medieval Tradition.” In King Arthur in the Medieval Low Countries. Edited by G. H. M. Claassens and David F. Johnson. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2000, pp 243-81.

Wells, D.A. “Source and Translation in the Moriaen.” European Context. Studies in the History and Literature of the Netherlands Presented to Theodoor Weevers. Cambridge: Modern Humanities Research Association, 1971. Pp. 30-58.

Read Less