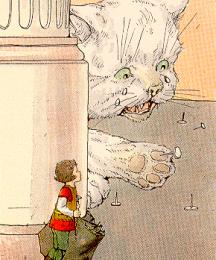

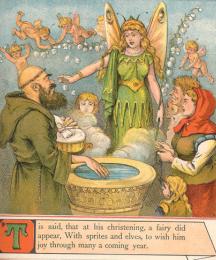

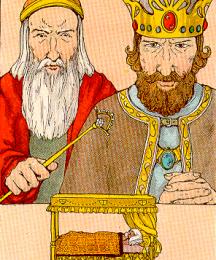

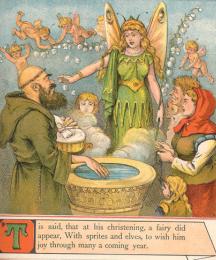

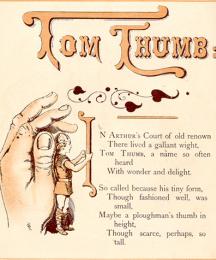

The earliest known prose version published in English, appears in a seventeenth-century chapbook entitled The History of Tom Thumbe, the Little, for his small stature surnamed, King Arthurs Dwarfe: Whose Life and adventures, containe many strange and wonderful accidents, published for the merry time-spenders (1621), written by Richard Johnson (listed only as R.I. on the title page). While King Arthur is a central figure in the tale, Johnson adds his own twist to the plot by including magical gifts given to Tom by his godmother, the Fairy Queen, his encounter with the giant, Gargantua, and his captivity in the giant's castle.

A later adaptation of Johnson's version is found in the chapbook, Tom Thumbe, His Life and Death: Wherein is declared many Maruailous Acts of Manhood, full of wonder, and strange merriments: Which little Knight lived in King Arthur's time,...

Read More

Read Less

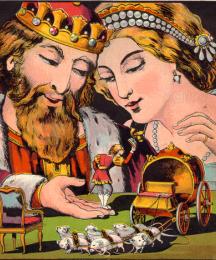

The legend of Tom Thumb began as a folktale of unknown ancient origins that is almost certainly based on an oral tradition. The novelty of Tom's adventures has clearly captured the imagination of people throughout the ages and across cultures, as demonstrated by the multicultural versions, as well as English adaptations to the tale. A significant number of retellings in the English traditions link the story to the Arthurian legend such as Merlin's role in Tom's birth, and the knighting of Tom by King Arthur. The evolution of the English legend can be traced back to seventeenth-century chapbooks that were published primarily for the entertainment of adults. By the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, playwrights adapted it for theatrical performance, and by the middle of the nineteenth century the story had moved into the realm of children's literature, where it remains today.

The earliest known prose version published in English, appears in a seventeenth-century chapbook entitled The History of Tom Thumbe, the Little, for his small stature surnamed, King Arthurs Dwarfe: Whose Life and adventures, containe many strange and wonderful accidents, published for the merry time-spenders (1621), written by Richard Johnson (listed only as R.I. on the title page). While King Arthur is a central figure in the tale, Johnson adds his own twist to the plot by including magical gifts given to Tom by his godmother, the Fairy Queen, his encounter with the giant, Gargantua, and his captivity in the giant's castle.

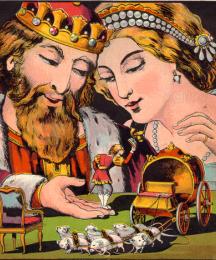

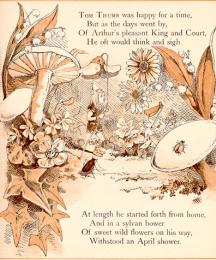

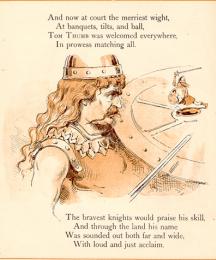

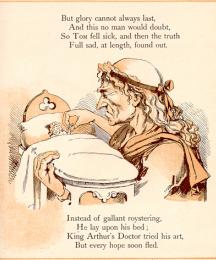

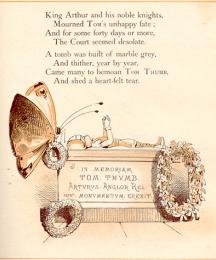

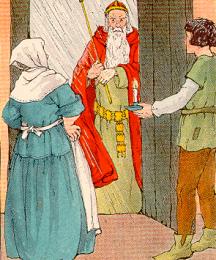

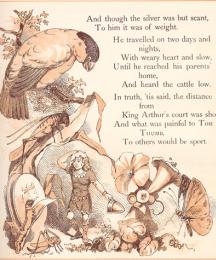

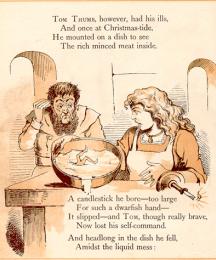

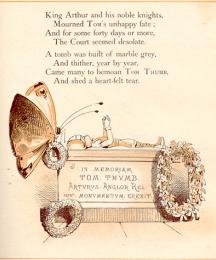

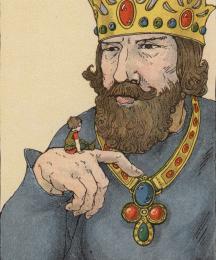

A later adaptation of Johnson's version is found in the chapbook, Tom Thumbe, His Life and Death: Wherein is declared many Maruailous Acts of Manhood, full of wonder, and strange merriments: Which little Knight lived in King Arthur's time, and famous in the Court of Great-Brittaine (1630). Written in verse, this adaptation includes Tom's parentage and the magic surrounding his birth when Merlin grants the wish of the ploughman's wife for a son even if he were no bigger than the ploughman's thumb. This version also includes Tom's popularity and noble deeds in King Arthur's court, but omits Johnson's embellishments. One hundred years later, playwright Henry Fielding, would rely on the popularity and general knowledge of Tom Thumb's story in writing his own version, ushering in a new phase in its evolution.

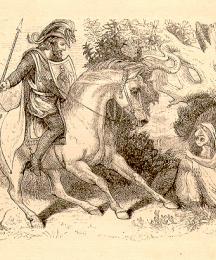

Fielding drew on the chapbook tradition of the earlier century in his satiric plays, Tom Thumb and The Tragedy of Tragedies. In Tom Thumb, the diminutive man is an unlikely hero as the conqueror of giants, a favorite in Arthur's court, and the object of women's desire. In 1730, Tom Thumb ran uninterrupted at the Little Theatre for nearly forty nights from Friday, April 24, until Monday, June 22. On March 24, 1731, Fielding released a revised version of the original Tom Thumb entitled, The Tragedy of Tragedies; or The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great, which ran through April and part of May, 1731.

Both plays contain liberal amounts of eighteenth-century political and literary satire, slurs on the medical profession, and parodies of earlier and contemporary heroic tragedies. In the critical introduction to his edition of the plays, editor L.J. Morrissey, notes that the political satire becomes clearer and is more obvious in the Tragedy of Tragedies adaptation, where it is immediately seen in the revised title which refers to Tom Thumb as "the Great." This is a direct reference to the politician, Sir Robert Walpole who was then called the "Great" man (6). Fielding was also ruthless in his literary parodies. He mercilessly scrutinized heroic tragedies, then lifted the most pompous and absurd lines from the texts and wove them into his own scenes, thus implying that these tragic portrayals and over-the-top emotions were comical and ridiculous.

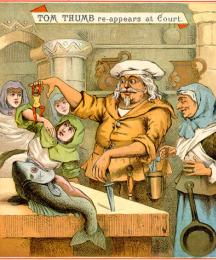

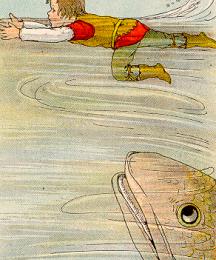

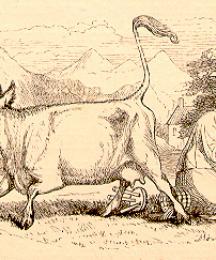

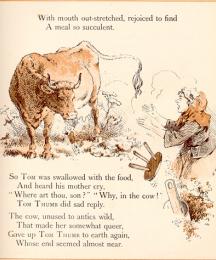

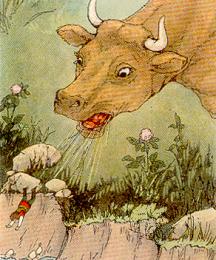

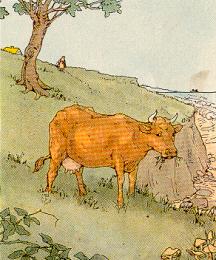

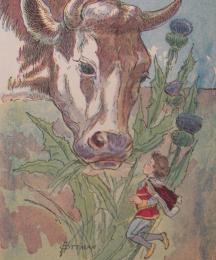

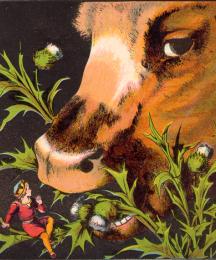

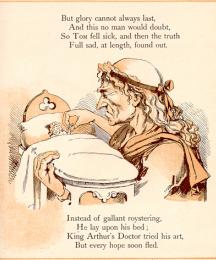

In the original version, Tom Thumb returns home the conquering hero and is promised the hand of the Princess Huncamunca, unleashing a chain of events because Arthur's queen, Dollalolla, is in love with Tom, and Lord Grizzle, a courtier, is in love with Huncamunca. Grizzle vows revenge and he and the queen conspire to stop the marriage. When an attempt is made on Tom's life and he is reported dead, by poisoning, the court is reduced to chaos until Tom's sudden reappearance. The king demands an explanation from the attending physicians who have mistaken a monkey dressed in Tom's clothes for Tom. Their ineptitude is a deliberate slur on physicians whom Fielding held in the highest contempt. Tom leaves the court and goes out into the street where Noodle witnesses his being swallowed by a large red cow. Grizzle is cheated of his revenge until Tom's ghost appears and Grizzle kills Tom's ghost. The court erupts in chaos once again, and in a frenzy of grief, each character is stabbed and dies. Arthur, the last left alive, kills himself.

The revised version, The Tragedy of Tragedies, begins in the same manner except for the addition of the character Glumdalca, the giant queen, and Foodle, Grizzle's accomplice. Dialogue has been added to Scenes IV and V in Act II, and in Act III, Scene IV, the dialogue between Princess Huncumunca and the King is longer, as well. However, it is in Acts II and III of The Tragedy of Tragedies that most of the revisions were made. In Act II, Scene V, Huncamunca promises to marry Grizzle after she has already agreed to marry Tom. In Scene VIII, the King reveals that he is in love with Glumdalca, who is in love with Tom; and in Scene X, Grizzle learns of Huncamunca's duplicity from Noodle. He confronts Huncamunca, and she tries to convince him that there is enough of her for both men. Grizzle swears revenge.

In Act III, Scenes I and II, Gaffer Thumb's ghost appears to Arthur and tells him of Grizzle's rebellion. Noodle confirms the story, and Tom and Glumdalca leave to stop the rebellion. In Scene VII, another new character, Foodle, is introduced as he and Grizzle plan their rebellion. On the way to fight Grizzle, Tom meets Merlin who tells him of the circumstances surrounding his birth and of his fate. During the battle, Grizzle kills Glumdalca, and Tom kills Grizzle, who swears to return to claim Huncamunca to be his in the after life. On his way back to court, bearing the head of Grizzle, Tom is swallowed by a large red cow, an event witnessed by Noodle who returns to court with the sad tale. Both endings are the same, as each character is stabbed and dies, leaving Arthur alone to kill himself. The popularity of Fielding's plays prompted an adaptation to the Tragedy of Tragedies in 1731 by playwrights, Eliza Haywood and William Hatchett.

The Opera of Operas; or Tom Thumb the Great opened on May 31, 1733 at the Little Theatre in the Haymarket but unlike Fielding who satirized heroic tragedy, Haywood satirized the conventions of the Italian opera, particularly their happy endings. In the "Introduction," to her edition of the play, editor Valerie C. Rudolph notes that, "Mrs. Haywood softens Fielding's satire on the heroic play by condensing or omitting speeches that originally focused on specific dramatic absurdities in order to heighten the satire on the Italian opera" (xvii). Consequently, two of the most notable differences between Fielding's adaptation and Haywood's are the satire Haywood employs regarding the improbability of happy endings, especially the improbability of political happy endings, and the inclusion of music.

As the entire cast lies in a dead heap on the stage, Haywood adds two commentators who argue about the absolute necessity of a happy ending if this was to be considered a true Italian opera. As the commentators debate, Merlin appears on the stage and tells the audience that the characters were under an enchantment. He lifts the enchantment and the dead characters rise; peace and order are restored in the court. Even more improbable is that all of the lovers who were in love with "the wrong person" suddenly realize that they are really in love with "the right person" and all promise to live in a spirit of peace and brotherhood forever.

In the late eighteenth century (1780), Kane O'Hara wrote a two-act burletta based on Haywood's adaptation. In his version, O'Hara omits characters and scenes entirely and changes some of the character's names. For example, O'Hara omits the scene in both Fielding and Haywood's versions where Tom has an encounter with a bailiff and his follower. O'Hara also changes the names of Huncamunca's ladies-in-waiting from Cleora and Mustacha to Frizaletta and Plumante. O'Hara does, however, retain the happy ending found in Haywood's adaptation.

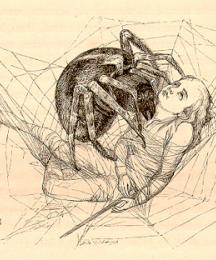

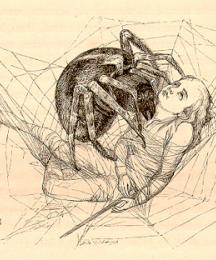

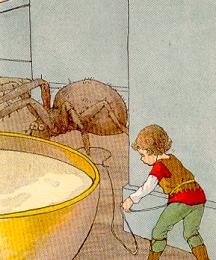

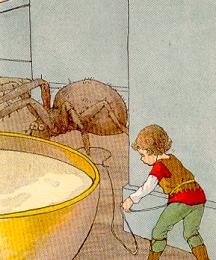

By the nineteenth century, the legend, originally aimed at an adult audience, generally becomes more temperate when the tale is modified for children by removing the coarseness of earlier versions and, in some versions, adding moralistic overtones. In Charlotte Mary Yonge's 1856 adaptation, Tom's elfin size causes his aunt to suspect him of demonic possession. Throughout the narrative he must resist his mischievous nature and numerous temptations by the impish elf Puck, who offers to help Tom out of his various mishaps if Tom would only admit to his elfin nature. Tom steadfastly refuses to do so. While recovering in Fairyland, he renounces his ties with the fairies, declares that he is a "Christian man", and demands to be returned to Earth in order to help Arthur fight Mordred's rebellion. Upon Tom's return, the rebellion is over, Mordred is dead and Arthur dying. Tom returns to Caerleon and agrees to escort Guinevere to a nunnery as his last duty as a knight of the Round Table. When he sees a spider's web around Arthur's chair at the Round Table, he tries to remove it but the devious spider weaves a web around Tom, binding him hand and foot. Puck, once again, offers to help Tom if he will admit to his own impish nature and return to fairyland. Tom refuses, preferring to die as an honorable Christian.

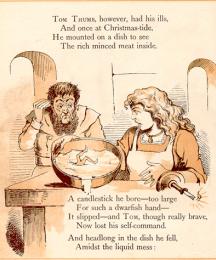

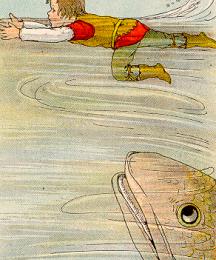

In 1863, Dinah Maria Craik Mulock compiled a collection of English fairy tales for children entitled, The Fairy Book. The Best Popular Fairy Stories Selected and Rendered Anew. In her adaptation, Mulock includes additions to the original narrative. She also chose not to condense or revise the story in order to make it suitable for a young audience. For example, when Grumbo, the giant, captures Tom in his castle, he swallows Tom like a pill only to "throw him up" into the sea when Tom makes his stomach uncomfortable. Mulock lets the narrative stand as a fairy tale, preferring to entertain children rather than instruct them on the virtues of moral behavior.

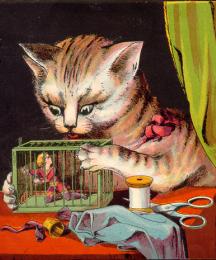

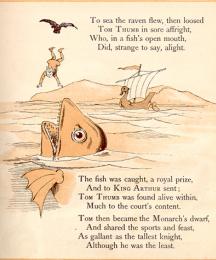

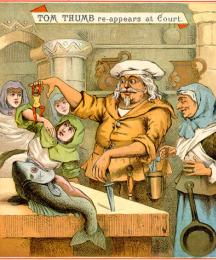

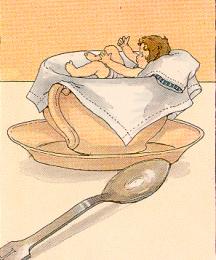

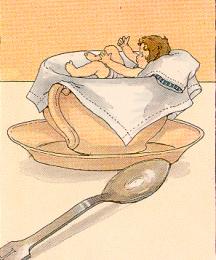

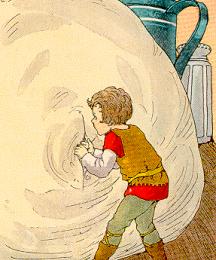

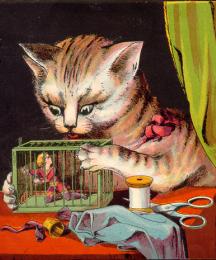

In Mulock's adaptation, the story does not end with Tom's death from over-exertion in jousting tournaments. Instead, after his death, Tom returns to Fairy Land until he is recovered. He is then sent back to Arthur's court where he immediately has an unpleasant encounter with the king's cook. A distracted Arthur orders Tom's execution, but Tom escapes by jumping down a miller's throat. He rolls about inside the miller who believes he is bewitched and calls a doctor. While the doctor is trying to diagnose the problem, the miller yawns and Tom jumps out of his mouth. He is seized by the angry miller and thrown into the river where he is swallowed by a salmon. When the fish is caught for the king's dinner, Tom again encounters his enemy the cook and is imprisoned in a mousetrap. A repentant Arthur eventually pardons Tom, knights him, and then takes him on a hunting trip, with a mouse as his steed. When a cat seizes the mouse, Tom fights the cat then dies from his injuries, returning once again to Fairy Land.

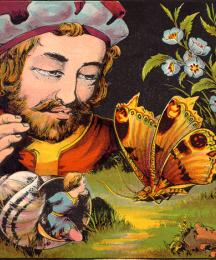

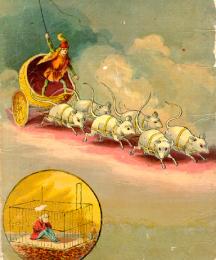

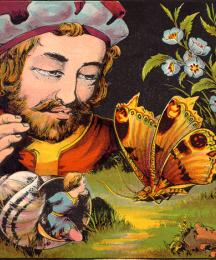

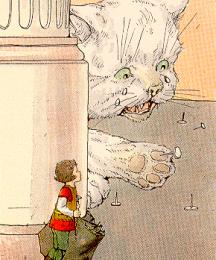

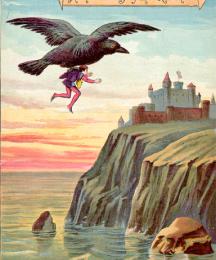

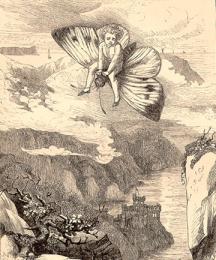

After many years, the Fairy Queen sends Tom back to earth where he becomes a favorite of King Thunston. Unfortunately, he soon falls out of favor with the queen and escapes from the palace on the back of a butterfly. The butterfly promptly flies back into the palace where Tom is captured. He is sentenced to death and imprisoned in a mousetrap awaiting execution. When a cat spies Tom in the trap, he thinks he is a mouse. The cat accidentally releases Tom who promptly falls into a spider's web and is mistaken for a fly. Tom fights the spider but is overtaken by its poisonous breath and dies. This time Tom returns to Fairy Land and remains there.

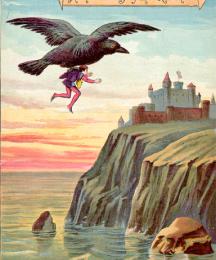

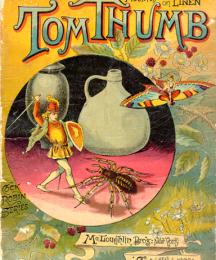

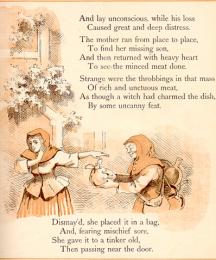

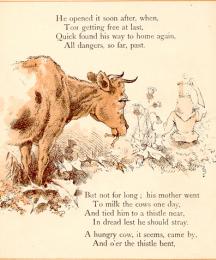

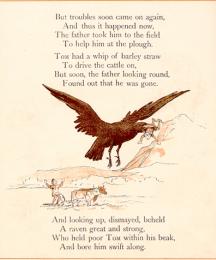

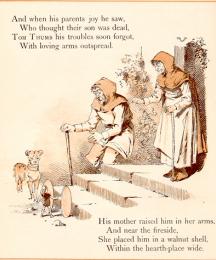

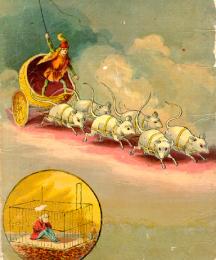

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the narrative is further adapted for children in a variety of illustrated books. In 1888, the McLoughlin Brothers published the picture book, Tom Thumb, mounted on linen. In this adaptation, Merlin and Mab, the Fairy Queen, conspire together to grant the ploughman's wish for a child and heir. In 1908, Thomas Nelson and Sons published, Adventures of a Fairy Knight. This lengthier version combines the story of Tom Thumb with several well-known Arthurian legends and fairy myths. For example, Merlin and Mab, the Fairy Queen, conspire to grant the ploughman's wish for a son because the King of the Fairies, Oberon, is jealous of the attentions the elf, Pigwiggan, has bestowed on Mab. For his own safety, Pigwiggan is sent to Earth as Tom Thumb. As a young boy, Tom retains his elfin nature and has adventures with a cow, a giant, and a fish. When he finds himself in Arthur's court after being released from the fish's stomach, he is befriended by the kitchen-boy, Gareth.

In Charles Stuart MacLeod's 1923 metrical version, we are told that Merlin makes Tom the size of his mother's thumb out of anger when the ploughman's wife refuses to give him food and shelter. In 1934, Helen and Bruce Gentry wrote The History of Tom Thumb. Published as a miniature book (3"x3"), this prose version retells Tom's adventures in the days of King Arthur. This version omits Tom's first death from over-exertion at jousting tournaments, and his return during King Thunston's reign. Instead, it remains in King Arthur's time. However, it is Arthur's queen who becomes jealous of the favors the king bestows on Tom, and who conspires to have him executed.

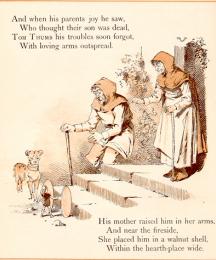

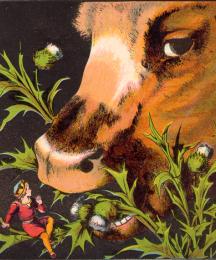

Many particulars of the narrative have also been modified for children. Some later versions change the thistle eaten by the cow to a flower. Tom never travels beyond the cow's mouth, nor is he unceremoniously deposited at the other end, as in earlier adult-oriented versions such as in the 1630 chapbook. Instead, he is saved by his mother or falls out of the cow's mouth after creating a commotion in her throat while trying to avoid her teeth. In some versions Tom lives happily in King Thunston's court until his death, while in others, he falls out of favor with the queen. The reason for his fall from favor is either not given, or is attributed to the queens jealously. Gerda Muller's 1988 version, The Adventures of Tom Thumb, omits Merlin from the story. Instead, Tom's father finds him lying inside a flower. In Richard Jesse Watson's 1989 version, King Arthur knights Tom after he rescues the king and the Knights of the Round Table from the giant Grumbong. The story ends when Tom returns home to his parents with a tiny wagon filled with coins given to him by King Arthur.

The story of Tom Thumb has also reached into popular culture. In the nineteenth century, the twenty-five inch tall Charles Sherwood Stratton was called, "General Tom Thumb," and became a sideshow attraction in P.T. Barnum's circus. Tom can also be found in a variety of twentieth-century animated videos. While many "Tom Thumb" animations have no connection to King Arthur, a few have retained that central theme from the early narratives. For example, the 1963 video Tom Thumb in King Arthur's Court, has a moralistic message: the size of a person's integrity is much more important than physical size. The evolution of Tom Thumb continues today. In her 2001 adaptation for children, The Adventures of Tom Thumb, Marianna Mayer brings the story of Tom Thumb in King Arthur's court into the twenty-first century in her retelling of the traditional story with new illustrations.

Despite a variety of changes, the legend of Tom Thumb has endured for more than three hundred years. Tom continues to amuse audiences with his mischievous nature and wit, while his bravery and perseverance, despite his size, secures his place as the smallest knight of the Round Table.

PRIMARY BIBLIOGRAPHY

CHAPBOOKS

1621. I., R. [Richard Johnson]. (1573-1659). The History of Tom Thumbe, the Little, for his small stature surnamed, King Arthvrs Dwarfe: Whose Life and aduentures containe many strange and wonderfull accidents, published for the delight of merry Time-spenders. London: 1621. Reprinted in A.B. of Phisike Doctour, Merrie Tales of the Mad Men of Gotamand R.I., The History of Tom Thumb. Ed. Curt F. Bübler, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1965.A prose tale published as a chapbook in London with King Arthur central to the tale. In this version, Tom is given magical clothes and gifts from the Queen of Fairies, and has an encounter with the giant, Gargantua.1630. Tom Thumbe, His Life and Death: Wherein is declared many Maruailous Acts of Manhood, full of wonder, and strange merriments: Which the little Knight lived in King Arthurs time, and famous in the Court of Great-Brittaine. London: Printed for John Wright, 1630.Written in verse, this adaptation of Johnson's 1621 prose version omits Tom's capture by a giant, the magical gifts from the Fairy Queen, and Tom's encounter with Gargantua found in Johnson's version.

PLAYS

1730. Fielding, Henry, (1707-1754). Tom Thumb. A Tragedy. Dublin: Printed and Sold by S. Powell, 1730. Reprinted in Tom Thumb and The Tragedy of Tragedies. Ed. L. J. Morrissey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970.Fielding's original play based on earlier metrical versions. In this adaptation, Tom Thumb becomes an unlikely hero and the object of women's desire in King Arthur's court. Fielding satirizes the absurdities of heroic drama and shows his contempt for government policies and officials.1731. Fielding, Henry, (1707-1754). The Tragedy of Tragedies or the Life and Death of Tom Thumb, the Great. As it is acted at the Theatre in the Hay-Market. With Annotations of H. Scriblerus Secundus. London: Printed and sold by F. Roberts in Warwick Lane, 1731. Reprinted in Tom Thumb and The Tragedy of Tragedies. Ed. L. J. Morrissey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970.This revision expands upon the parodies found in Fielding's first version by adding scenes, complications, and characters that broaden and enhance the satire aimed at government, heroic drama, etc.1733. Haywood. Eliza (1693-1756) and Hatchett, William (1730-1741). The Opera of Operas; or, Tom Thumb the Great. Alter'd from the life and death of Tom Thumb the Great. And set to musick after the Italian Manner. As it is performing at the New Theatre in the Hay-Market. London: Printed for William Rayner, 1733. Reprinted in The Plays of Eliza Haywood. Ed. Valerie C. Rudolph. New York: Garland Publishing, 1983.An adaptation of Henry Fielding's play The Tragedy of Tragedies, and set to music. Rather than focusing on political or literary satire, Haywood's version uses the diminutive hero and the scheming, lecherous court to heighten her satire on the popular happy endings found in Italian opera.1780. O'Hara, Kane (arr.) (1714?-1782). Tom Thumb. A Burlesque Opera. Altered from Fielding, Henry. First performed in 1780. First Printed in 1805. Reprinted in British Drama, 12 vols., John Dicks, 1871, VI (219-24).A burletta based on Fielding's 1731 burlesque, The Tragedy of Tragedies. This shortened version changes or omits scenes and characters while retaining Fielding's acerbic satire on politics and heroic drama. Like Haywood's adaptation, this burletta's happy ending satirizes the happy endings in Italian opera.(c.1800). Tom Thumb: Printed for the Booksellers, n.d. [generally dated from 1790-1810].

Metrical version printed in a late eighteenth century or early nineteenth-century chapbook. Adapted from the earlier ballad version Life and death of Tom Thumbe printed for John Wright in 1630.

CHILDREN'S BOOKS

1856. Yonge, Charlotte Mary, (1823-1901). The History of Sir Thomas Thumb. Ill. J.B. Edinburgh: Thomas Constable and Co., 1856.A moralistic slant is given to this adaptation in which Tom must resist his own mischievous nature in order to perform his duty. He is tempted and mocked by the impish Puck who offers to help him out of his various mishaps if Tom will admit to his elfin nature, which Tom steadfastly refuses to do. It also combines Arthurian tales with the story of Tom Thumb. Tom leaves his parents to go to Caerleon and seek his fortune. There, he becomes a favorite of the court. His loyalty and courage are rewarded when King Arthur knights him. He assists King Arthur in solving Dame Ragnelle's riddle, but when Tom learns of Mordred's planned rebellion, he is seriously wounded by Mordred and taken to Fairyland to recover. Puck again tries to convince Tom to stay in Fairyland rather than returning to Earth. Tom refuses, insisting that he is a good Chrisitan man and will do his duty. However, upon his return, Tom finds Arthur mortally wounded. After Arthur's death, he agrees to escort Guinevere to a nunnery as his last duty as a knight of the Round Table. On the night before they were to leave, Tom is incensed at the sight of a spider web on King Arthur's chair. While he tries to remove the web, the spider weaves another around him. Bound hand and foot in the spider's web, Tom is tempted one last time by Puck, who offers to free him if he will acknowledge his own impish nature. Tom refuses, preferring to die an honorable Christian death.1863. Mulock (Craik), Dinah Maria (1826-1887). Tom Thumb. Taken from The Fairy Book. The Best Popular Fairy Stories Selected and Rendered Anew. London: MacMillan and Co., 1863.A prose version of Tom Thumb that is part of a collection of English fairy tales for children. Mulock did not condense or revise this version of Tom Thumb in order to make it more suitable for a younger audience. It does include additions to the original version in which Tom dies and returns to life with the help for the Fairy Queen, has an unfortunate encounter with the royal cook and a cat, and dies after a valiant battle with a poisonous spider.?1880-1885. M., C. The Merry Ballads of Olden Time. Ill. Emrik & Binger. London: F. Warne & Co., [?1880-1885].A metrical version of Tom's adventures with a cow, a raven, and a fish that brings him to King Arthur's Court where he becomes a favorite of the King.?1880-1889. The Story of Tom Thumb. Familiar Stories Picture Book. New York: McLoughlin Bros.,[?1880-1889].The history of Tom is told in a short metrical version for children. Each verse is followed by a captioned illustration.1888. Tom Thumb. From the Cock Robin Series. New York: McLoughlin Bros., 1888.An illustrated picture book written in prose and mounted on linen. Merlin and Mab, the fairy queen, work together in this version to grant the wish of the ploughman and his wife for a child.1908. Sir Thomas Thumb, or, The Wonderful Adventures of a Fairy Knight. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1908.This lengthy version combines Tom's adventures with a number of Arthurian stories and fairy myths. The book begins with Merlin's background and his association with Mab, the Fairy Queen. They conspire to grant the ploughman's wish for a son in order to remove the elf, Pigwiggan, from King Oberon's jealous reach even though by becoming mortal the elf will become subject to all human ailments. After Tom is born, he retains his elfin nature and has adventures in a cow's mouth, a giant's castle, and a fish's stomach where he gains entry into King Arthur's court. There, he meets and is befriended by Gareth, the kitchen-boy, after being released from the fish. He meets his old friend, Puck, on his way home with money for his parents, and receives news from fairyland. He embarks on a new set of adventures with Puck and other fairies until his return to Arthur's court where he is knighted. After a cat injures Tom, while on a hunting trip with the king, he lies unconscious in Arthur's court while his spirit returns to fairyland. The fairy knight challenges King Oberon to a fight. They battle until they are given water that induces forgetfulness. Oberon and Mab are reunited, and Tom returns to Camelot only to learn that Arthur and his loyal knights are off fighting Mordred's rebellion, Guinevere is in a nunnery, and Sir Lancelot is at Joyous Gard. Tom faints. When he awakens once more, he learns that there is a new monarch, King Thunston. The new king takes a liking to Tom, but Thunston's queen becomes jealous. To escape being put to death, Tom hides under a snail shell, flies out of the palace on the back of a butterfly, and is almost drowned in a pail of water. He is imprisoned in a mousetrap and when a cat accidentally sets him free, King Thunston takes pity on him and pardons him. Soon after, Tom is attacked by a giant spider in the king's garden and dies.1912. Tom Thumb. Chicago: M.A. Donohue & Co.,1912.An illustrated picture book written in prose relating Tom's many adventures with a cow, a raven, a fish, and his being knighted by King Arthur. After his death from over-exertion in jousting tournaments, he is taken up to Fairy Land to recover. When he returns to Arthur's court he immediately angers the king's cook, is tried for high treason, and must be rescued by the Queen of the Fairies. The third and last time he returns to earth, he hides in a snail shell until he can jump on the back of a butterfly that brings him to King Thunston's court where he lives happily until he is overcome by a spider's poisonous breath.1923. MacLeod, Charles Stuart. Tom Thumb. Ill. Margaret Campbell Hoopes. Philadelphia: Henry Altemus Co., 1923.In this story, written in verse, an angry Merlin makes Tom as small as his mother's thumb because she refuses to give him food and shelter. Later, a naughty Tom is exiled from Arthur's court because he cannot control his mischievous behavior.1934. The History of Tom Thumb. Ill. Hilda Scott. San Francisco: 1Helen and Bruce Gentry, 1934.A miniature (3"x3") prose version that relates the story of the life and death of Tom Thumb in the days of King Arthur.1934 Tom Thumb. Ill. Eulalie. New York: Platt & Munk Co., Inc., 1934.Merlin is excluded from this short and condensed story. No explanation is given for Tom's size but his adventures include falling into a bowl of batter, being snatched from his father's field by a crow that drops him on a giant's castle, and being swallowed by a fish that brings him to King Arthur's court. This version also includes Tom's return to Earth after his death, aided by the Queen of the Fairies.1934. Johnson, Clifton. Tom Thumb. Ill. Harry L. Smith. Chicago: The Goldsmith Publishing Co., 1935.A very different version relating a new series of adventures for the mischievous Tom who is kidnapped by travelers who want to display him in a freak show. His adventures include an escape down a mouse hole, the outwitting of two thieves, being swallowed by a cow, and being thrown into a garbage heap and then swallowed by a wolf. The story does retain the character of Merlin who grants the farmer his wish for a son.1940. Tom Thumb also Drakestail. Ed. Katherine Lee Bates. Ill. Margaret Evans Price. Chicago: Rand McNally & Co., 1940.In this adaptation, Merlin goes to the queen of the fairies and asks her to grant the ploughman's wish for a son. This retelling retains Tom's mischievous nature, his perilous adventures with a red cow, a giant, and a fish that brings him to King Arthur's court where he becomes the court dwarf. When Tom becomes ill, he is taken back to Fairyland to recover. He is sent back to earth, but immediately has an unpleasant encounter with the king's cook and is sentenced to be beheaded. He jumps down a miller's throat then escapes by jumping into the river where he is swallowed by another fish that is brought to King Arthur's cook. Tom is brought before the king who forgives him and then knights him. He is given a mouse to ride, and a tailor's needle for a sword. When the mouse is attacked by a cat, Tom is injured trying to protect the mouse and is taken back to Fairyland to recover. The Fairy Queen sends him back to earth again, but the time of King Arthur has passed. He becomes a favorite of King Thunston where he lives happily for many years until his death.1988. The Adventures of Tom Thumb. Designed and illustrated by Gerda Muller. London: Treasure Press, 1988.Tom's father finds him in a flower. This adaptation portrays Tom as a kind, thoughtful child who likes to read and write rather than as the sly, mischievous child of earlier versions. He is brought to King Arthur's court after being swallowed by a fish but is hated by the courtiers who refuse to help him when he is attacked by a cat. He is taken to fairyland to recover, then returned to his parents where he remains only visiting the king and queen.1989. Watson, Richard Jesse. Tom Thumb. Ill. Richard Jesse Watson. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich Publishers, 1989.A modern version which adapts the original version of Tom's mysterious birth and his perilous adventures. Tom becomes a hero and earns his place at the Round Table when he saves King Arthur and his Knights from the giant Grumbong. The king is so grateful that he offers Tom all the gold he wants to take back to his parents. Tom returns home triumphantly riding his mouse and following a tiny cartful of gold coins.2001. Mayer, Marianna. The Adventures of Tom Thumb. Ill. K.Y. Craft. New York: SeaStar Books, 2001.Merlin grants Tim and Kate a son who is no bigger than Tim's thumb. Despite protection by his fairy godmother, Tom endures a series of unfortunate accidents before he saves the land from Gembo the giant. He is knighted by King Arthur for his bravery then returns home to his parents because he misses them.

ANIMATION

1959. "Tom Thumb," Fractured Fairy Tales, Rocky and His Friends series, 1959."Tom Thumb story with Arthurian references; satirically explores the problem of juvenile delinquency." (Not viewed). Description taken from Michael N. Salda's bibliography of Arthurian animation on The Camelot Project, The University of Rochester.1963. I Was A Teenage Thumb. Warner Bros., 1963."Tom Thumb story with several Arthurian references." (Not viewed). Description taken from Michael N. Salda's bibliography of Arthurian animation on The Camelot Project, The University of Rochester.1963. Tom Thumb in King Arthur's Court. Coronet, 1963.A retelling of Tom's adventures in King Arthur's court where true valor is not determined by size but by spirit and resolve.1991. Tom Thumb. Gary Delfiner Productions; World-Vision Home Video, Inc., 1991."Retelling with Tom saving Arthur's court from a giant; based on Richard Jesse Watson's story." (Not viewed). Description taken from Michael N. Salda's bibliography of Arthurian animation on The Camelot Project, The University of Rochester.

SECONDARY BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Camelot Project. The University of Rochester. http://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot-project

A database of Arthurian texts, images and bibliographies.

Carpenter, Humphrey and Prichard, Mari. The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Briefly mentions changes made to the narrative especially in the eighteenth century and in the nineteenth century versions for children. Also includes suggestions for further reading.

The London Stage 1660 - 1800. Part 3: 1729-1747. Ed. Arthur H. Scouten. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1961.

A history of plays, afterpieces, and casts with commentaries and box office receipts. Taken from playbills, newspapers, and theatrical diaries of the period. Tom Thumb is listed as the afterpiece on Friday, April 24, 1730 playing at the Haymarket Theater and on Saturday, April 25, includes the comment, "Prince of Wales present."

Nicoll, Allardyce. A History of English Drama 1660-1900. Vol. II. Early Eighteenth Century Drama, Third Edition. Cambridge: The University Press, 1955.

A hand-list of plays with a register of performances that include plays written by Henry Fielding and Eliza Haywood. Opening dates for Fielding's Tom Thumb in 1730, and The Tragedy of Tragedies in 1731, as well as subsequent performances of The Tragedy of Tragedies in 1737, 1743, 1751, 1765 and 1776 are listed. Entries for Eliza Haywood are dated from 1721 to 1733, with a register of performances from 1733-1740. The burletta, The Opera of Operas; or Tom Thumb the Great, co-authored with William Hatchett, credits the music to Arne. A later alteration to the text, retains the title but credits the music to Mr. Lampe.

Perceval, John. Manuscripts of the Earl of Egmont. Diary of Viscount Percival Afterwards First Earl of Egmont. Vol. I. 1730-1733, pg. 97. London: His Majesty's Stationary Office, 1920.

In his diary, the Earl of Egmont mentions his attendance at the Haymarket playhouse to see Fielding's play, Tom Thumb, on Friday, April 24, 1730. In his remarks, he notes that while the play ridicules poets and their work, modern tragedians, and operas, it is full of humor and some wit. The entry also includes a personal comment on Henry Fielding, saying that he is one of "Mr. Fielding's sixteen children and in a very low condition of purse."

Prescott, Ann Lake. The Odd Couple: Gargantua and Tom Thumb. Printed in Monster Theory. Ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996: 75-91.

This article examines cultural perceptions regarding size. The fascination with the humor and terror associated with those perceptions are presented through the encounters and juxtapositions found in literature between the giant, Gargantua, and the pygmy, Tom Thumb.

Rivero, Albert J. The Plays of Henry Fielding: A Critical Study of His Dramatic Career. Charlottsville: University Press of Virginia, 1989.

Contains a critical essay on the chaotic language and misuse of language employed by Fielding in his satirical plays, Tom Thumb and The Tragedy of Tragedies, as methods of deconstructing the structure of tragedies and heroic plays.

Storytelling Encyclopedia. Historical, Cultural, and Multiethnic Approaches to Oral Traditions Around the World. Ed. David Adams Leeming. Phoenix: Oryx Press, 1997.

Short synopsis on the history of the legend and the different versions including Fielding's and Yonge's. Also includes later English versions that are based on German folk-tales and its establishment by the mid-eighteenth century as a children's story.

Weiss, Harry B. "Three Hundred Years of Tom Thumb." The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 34. (Jan. to June 1932): 157-66.

A three hundred year history of the legend of Tom Thumb that examines many of the changes and adaptations made to the tale.

Read Less

![Title Page [to 1912 Tom Thumb]](https://d.lib.rochester.edu/sites/default/files/styles/creatorpage/public/WOTitle_0.jpg?itok=mMki_LBd)

Never you fear, father; I will sit in the horse's ear and tell him which way to go.

Never you fear, father; I will sit in the horse's ear and tell him which way to go.by Jemima Blackburn

1855

Title Page 1 for The History of the Life and Death of the Good Knight Sir Thomas Thumb

Title Page 1 for The History of the Life and Death of the Good Knight Sir Thomas Thumbby Jemima Blackburn

1855

Images Gallery

![Title Page [to 1912 Tom Thumb]](https://d.lib.rochester.edu/sites/default/files/styles/creatorpage/public/WOTitle_0.jpg?itok=mMki_LBd)