Read Less

Taliesin "of the shining brow" is a mytho-historical character generally associated with early Wales and North Western Britain in the 6

th century AD. He is a figure belonging to both history, as an important Old Welsh court poet, and to mythology, as a magician and seer in both Celtic and Arthurian legend. The fictive and quasi-fictive literature that uses Taliesin, as either a significant or minor character, often combines these two aspects to varying degrees: he is depicted as both a poet (though rarely in the historically accurate court) and as a seer in possession of magical or seemingly magical powers and knowledge. However, historians and literary scholars are careful to keep the two figures separate.

Taliesin Ben Beirdd (chief of the bards), as Taliesin the poet is also known, is considered one of the most significant Old Welsh bards. The poems associated with him are perhaps the oldest surviving Old Welsh poems and because of this some scholars of Welsh literary tradition, such as Saunder’s Lewis, have referred to the Welsh poetic tradition that followed as “Taliesinic.” What’s more, he is also frequently used as an iconic symbol of Welsh literature and poetry.

Taliesin is historically associated with the courts of King Urien and Owain ab Urien of Rheged One early and well known biographer, Sir Ifor Williams (1881-1965), posits an earlier career in the more southerly Powys and positions him as bard to the chieftain Cynan Garwyn. He bases this hypothesis on suggestions from the poems themselves, though these surmises, as well as the correct dating of the work attributed to Taliesin, have come under some debate for both linguistic and contextual reasons. Indeed a number of the poems attributed to Taliesin have been dated to a much later period: stylistic and grammatical elements place them as late as the twelfth century. The historicity of Taliesin is further complicated by issues of translation. Much of the Old Welsh comes to us first translated by Middle Welsh intermediaries which were recopied, if not invented, centuries later.

The earliest mention of Taliesin before the Brythonic period, with which King Arthur is associated, is a line from the

Gododdin where he is referred to as one who is skilled in expression (Griffen 22). He is also briefly mentioned by Nennius in the 9

th century text

Historia Brittonum. Here he is referred to as one of several famous bards from the time of Myrddin/Merlin: "Then Talhaern Tataguen gained renown in poetry, and Neirin and Taliesin and Bluchbard and Cian, who is called Gueinth Guaut, gained renown at the same time in British poetry"(Wood 8). While both Arthur and Taliesin are treated as historical figures in the

Historia, Taliesin is not directly associated with Arthur in this text.

The poems attributed to Taliesin, and which have thus solidified his position for many as an actual historical figure and poet, are found in three primary groups: The

Llyfr Taliesin, The

Ystoria Taliesin, and the

Black Book of Carmarthen and the

Red Book of Hergest. The

Black Book, also known as the

Llyfr Du Caerfyrddin, is the earliest of these manuscripts and has been dated circa 1250.

The Red Book, or

Llyfr Coch Hergest, is more recent. The earlier of the two manuscripts has been dated circa 1382 and the second 1410. These two books are perhaps best known for their influence upon the better known work of Lady Charlotte Guest, specifically her edition of

The Mabinogion, which itself has become the most common source of Taliesin legends for many readers.

The Mabinogion, however, focuses on the mythological, and magical, elements of the Taliesin figure.

Like the

Red Book and

Black Book, the

Llyfr Taliesin (Book of Taliesin) and the

Ystoria Taliesin, contain poetry commonly attributed to Taliesin. While the manuscript of the

Llyfr is from the mid14

th century, the

Ystoria is dated to the late 16

th century and the poems found therein are not generally considered works written by a historical Taliesin, as they come from very late in the tradition and are attributed to a Taliesin who is familiar with the court of Arthur, and who began composing poetry the moment he was fished out of the sea as an infant and who made prophetic announcements as a youth. Essentially this is the same mythological figure that we find in the Red and Black Books. Therefore historical scholars do not attribute them to any particular historical figure or writer. Of the fifty-six poems found in the

Llyfr Taliesin, only a dozen are considered to be fully authentic works, composed by a historical Taliesin. These twelve poems are said to date from the second half of the sixth century and are some of the earliest Welsh and non-Latin vernacular poems in Europe. For this reason Taliesin is considered, along with his contemporary Aneirin, a founder of the Welsh poetic tradition. Taliesin’s panegyric pieces were typically either elegiac laments for the deaths of heroes, celebrations of martial victory, or, most commonly, poems in praise of a king or chieftain.

Of course this is only one half of the Taliesin tradition: that of the living poet and historical figure. The second half, and the one which brings him into contact with the Arthurian tradition, centers on his role as a bardic sage, seer, and magician. He is often depicted in the tradition of a Merlin figure, and is quite often paired or associated with Merlin himself in Celtic and Arthurian traditions. Indeed, in Geoffrey of Monmoth's

Vita Merlini, Taliesin plays the role of a student of Gildas and friend to Merlin. In the

Vita, it is to Taliesin that Merlin explains his history. In exchange, Taliesin gives a lengthy explanation of the various magical springs and fountains which exist in the world. In this dialogue Taliesin is pictured as a knowledgeable co-wise man/prophet figure.

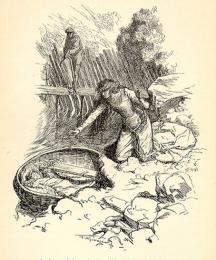

Many of the stories surrounding his persona are highly fantastical and part of a broader Celtic mythos. As a sort of god or demi-god figure, Taliesin is sometimes depicted as a magically enlightened shape-shifter, one whose tale is often compared to the story of the Irish hero Fionn mac Cumhail and the salmon of wisdom. The

Ystoria Taliesin contains the tale of Gwion Bach who accidentally receives wisdom and poetic inspiration from the cauldron of the goddess/sorceress Ceridwen, and who uses his newfound abilities to shape-shift in order to escape her. The modern reader may find the tale charmingly reminiscent of the "wizard's duel" between Merlin and Madam Mim in the animated film

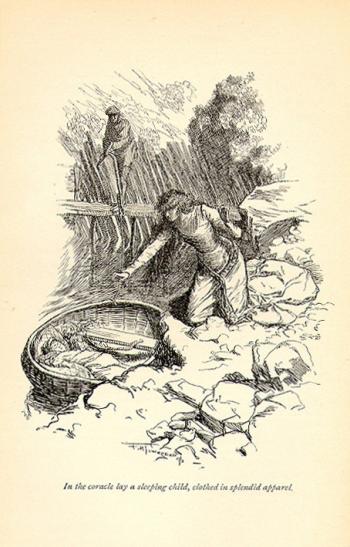

The Sword in the Stone. Eventually Ceridwen swallows Gwion Bach as a grain of wheat and he is afterward reborn as Taliesin. The goddess cannot bring herself to destroy him outright and so instead sets him adrift in a seal-skin bag. He is rescued in a fishing weir and is named and raised by Elphin.

In the

The Mabinogion of Lady Charlotte Guest, Taliesin’s birth is depicted as occurring during the beginning of the time of Arthur and the Round Table, though it does not immediately connect him to Arthur's court. Indeed, there are relatively few explicit connections made between Taliesin and King Arthur in the Welsh pieces. Another source, "The Spoils of Annwfn," a relatively brief tenth-century poem, describes how Taliesin joined Arthur and his warriors on a raid of the otherworld, but this seems to be a rare instance of a link between the bard and Arthur in Welsh tradition.

Outside of historical and pseudo-historical texts, Taliesin made almost no major appearances in non-Welsh medieval texts and remained for the most part outside of the medieval romance tradition of King Arthur. One rare exception to this is his mention in the tale

Culhwch and Owen, where he is referred to in a passing reference as a bard in Arthur's court.

In Lord Alfred Tennyson's "Idylls of the King" (1833-1874), Taliesin makes another brief appearance as a court bard and is specifically associated with the court of Arthur, if fleetingly. This is of course a much later work, and part of the Victorian revival of medieval and Arthurian romance. Taliesin makes similarly limited appearances in a few minor works as well, such as his reprisal of the role of Arthur's bard in Thewall's

The Fairy of the Lake (c.1801). He takes a much larger role in Richard Hovey's

Taliesin: A Masque (1900)

, which posits Taliesin as a bard who encounters Percival and assists in his grail quest. The plot is generally subjugated to music and poetic effect, but it does make Taliesin not only a primary character in terms of stage time, but also thematically important because of his bardic attributes. One 19th century work that makes use of Taliesin’s Welsh mythological tradition instead of simply depicting him as an Arthurian bard is Thomas Love Peacock’s

The Misfortunes of Elphin (1829), a pseudo historical novel which follows the life of Elphin, including his catching an infant in a fishing weir, naming him Taliesin, shining brow, because of his beauty, and then educating the poetry-reciting child prodigy.

Beyond this, Taliesin continued to be largely ignored until the twentieth century. Charles Williams'

Taliesin through Logres (1938) and

The Region of the Summer Stars (1944) reintroduce the character in his role as King Arthur's bard. However, in this instance it is no mere passing reference to the character. In these collections of poetry, Taliesin is not only a constant presence; he is the very eye through which events are witnessed and oftentimes is the poems' narrator. Williams also depicts him as an embodiment of the poetic spirit, a notion that is picked up and carried on by other writers. This includes poets such as Vernon Watkins who has several poems devoted to Taliesin as a poetic prophet and creative spirit, though without the Arthurian context. These include “Taliesin at Pwlldu,” “Taliesin’s Voyage,” “Taliesin and the Mockers,” and “Taliesin and the Spring of Vision.” His role in Watkins’s verse is very much in keeping with his alternate historical position as a father and embodiment of Welsh poetic traditions as well as his functioning as bard and prophet in both the historical and mythical traditions.

A number of later works, most of which belong to the genres of fantasy and science fiction, continue to depict Taliesin as either a member of Arthur's court or at least as a key figure in the legends surrounding other, better known Arthurian personages. The best known and most popular of these works are Stephen Lawhead's

Taliesin, and Marion Zimmer Bradley's

The Mists of Avalon. Lawhead's

Taliesin (1988) is the first book of his epic Arthurian "historical fantasy" series,

The Pendragon Cycle. Taliesin borrows a great deal from various mythological traditions and posits the bard and prophet Taliesin and the Lady of the Lake, an Atlantian princess named Charis, as the parents of Merlin, who will later, and famously, play a vital role in the story of Arthur's birth and ascension to the throne. Bradley similarly associates Taliesin with Merlin, though in a much different way. In

The Mists of Avalon (1982) Taliesin

is Merlin, Merlin being the title of the chief bard (or druid) of Britain rather than a proper name. He does not remain "Merlin," however, as he dies in this account and is succeeded by another druid by the name of Kevin. It is this Merlin, Taliesin's replacement, to whom Bradley attributes the tale of Nimue's seduction and betrayal.

There are a number of other works, such as

Taliesin and King Arthur (1970), a children's book by Ruth Robbins, or Guy Gavriel Kay's

The Fionavar Tapestry (1987), which also posit Taliesin as Arthur's personal bard, or "harper." John Matthews, in works such as

The Song of Taliesin: Tales from King Arthur's Bard (2001), returns Taliesin to a role similar to that in Charles Williams' works, though in a pseudo-historical manner which utilizes the actual poetry attributed to Taliesin, and in a manner evocative of the tales of the

Mabinogion. Here he is both Celtic shaman and court bard to King Arthur, fusing Taliesin’s pseudo-historical with his mythic depicitons.

The Taliesin tradition in modern literature seems to have fared as well, or better, without its connections to the Arthurian legend, though in a few cases he finds himself in similar roles as those he plays in the Arthurian tradition. For example, Taliesin plays a relatively small role as the Chief Bard of Prydain in Lloyd Alexander's

Chronicles of Prydain series (1964-1969). The vast majority of this series highlights those aspects of Taliesin related to his roll as magician, prophet, or druid and seems to come directly from the Celtic traditions. In the cyberpunk science-fiction novel

The Adventures of Redman Red (2006) by Nathaniel Haynes, the protagonist undergoes a vision quest and enters a fairy realm as a salmon. There he meets a king who identifies the protagonist as an incarnation of Taliesin, thus drawing on both Taliesin's shape-shifting abilities and his connection to Fionn mac Cumhail. Similarly,

Just Like A Fairy Tale (2007), by Sophia Babai makes Taliesin a primary character and pulls its inspiration from the

Mabinogion despite its being set in a modern period.

Other imaginings of Taliesin don't call on any previous tradition and are instead an embodiment of modern conceptions of what bards, or druidic figures of Celtic lore, might look like, particularly in the context of their “other-worldliness.” The fantasy novel,

Moonheart, pictures him as a bard in an otherworld, and Traci Harding’s

The Ancient Future depicts Taliesin Pen Beirdd as a magician figure who can transport the primary character through time. Of course these depictions may not be explicitly connected to the canonical traditions of Taliesin lore and literature, but they do have something in common with the early traditions surrounding Taliesin; namely, he is a temporally luminal character who seems, in most incarnations, to be unbounded by the laws of time, place, and context. His association with Arthur is in the first place anachronistic, but this seems fitting to one whose creation legend contains multiple re-births: first by magical inspiration, second by literal passage through the goddess Ceridwen, and finally, as a babe set adrift at sea to be rediscovered in the tradition of many mytho-heroic figures.

It is safe to say that in any incarnation and in any context, Taliesin carries with him an air of one who, like most mythic figures, exceeds boundaries. He also posseses an exceptional understanding and grasp of the power of vision and language, be it of the supernatural and magical variety or simply that of a great poet. He is often depicted as a seer and guide for others; in some manner he is also a guide for the poets, artists, playwrights, and novelists who have taken up his myth or looked to it for artistic inspiration. Even architects can be added to that list. Frank Lloyd Wright named more than one of his homes after the Bard in honor of his Welsh heritage. The first of these, Taliesin I, was situated upon a favorite hill to become a literal as well as figurative “shining brow.” Taliesin’s powers of prescience and his uncanny knowledge are perhaps not so much magical, then, as they are a reflection of an artist’s powers of perception and creative vision.

BibliographyAlexander, Lloyd. The High King. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968.

Bond, Nancy. A String in the Harp. New York: Atheneum, 1977

Bradley, Marion Zimmer. The Mists of Avalon. New York: Knopf, 1982

Bruce, W. Christopher. The Arthurian Name Dictionary. New York: Garland publishing, 1999.

Culhwch and Olwen: An Edition and Study of the Oldest Arthurian Tale. Ed. Rachel Bromwich and D. Simon Evans. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1992.

De Lint, Charles. Moonheart. New York: Orb Books, 1994.

Evans, Stephen S. The Heroic Poetry of Dark-Age Britain: An Introduction to Its Dating, Composition, and Use as a Historical Source. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1997.

Geoffrey of Monmouth. Vita Merlini. Ed. Basil Clarke. Cardiff: University of Wales Press [for] theLanguage and Literature Committee of the Board of Celtic Studies, 1973.

Griffen, Toby D. Names from the Dawn of British Legend: Taliesin, Aneirin, Myrddin/Merlin, Arthur. Felinfach, Lampeter, Dyfed, Wales: Llanerch Publishers, 1994.

Harding, Traci. The Ancient Future: The Dark Ages. Pymble, N.S.W.: HarperCollins, 1996.

Haycock, Marged. Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin. Aberystwyth: CMCS, 2007.

Haynes, Nathaniel. The Adventures of Redman Red. Mavern: Nick Hall, 2006.

Hovey, Richard. Taliesin: A Masque. Boston: Small, Maynard and Co., 1900.

Kay, Guy Gavriel. The Summer Tree. New York: ROC, 2001.

Koch, John, and John Carey. The Celtic Heroic Age. 3rd ed. Malden, Mass.: Celtic Studies Publishing, 2003.

Lawhead, Stephen R. Taliesin. NewYork: EOS, 1999.

Lewis, Saunders. “The Tradition of Taliesin.” THSC (Transactions of the Honorable Society of Cymmrodorion). (1968): pp.293-98.

Llyfr du Caerfyrddi: The Black Book of Carmarthen. Trans. Merion Pennar; Ill. James Negus; Welsh Diplomatic Text by J. Gwenogvryn Evans. Lampeter: Llanerch, 1989.

Mabinogion: from the Llyfr Coch o Hergest. Trans. Charlotte Guest; Ill. Jo Nathan; Ed. Owen Edwards. Felinfach: Llanerch, 1990.

Mathews, John. Taliesin: Shamanism and the Bardic Mysteries in Britain and Ireland. London: Aquarian Press, 1991.

Medieval Welsh Poems. Ed. Clancy, Joseph P. Portland: Four Courts Press, 2003.

Peacock, Thomas Love. The Misfortunes of Elphin. London: Thomas Hookham,1829.

Robbins, Ruth. Taliesin and King Arthur. Berkeley: Parnassus Press, 1970.

Sampson, Fay. Taliesin's Telling: Book Four in the Sequence Daughter of Tintagel. London: Headline, 1991.

Tennyson, Alfred. Idylls of the King. London: Macmillan and Co., 1907.

The Historia Brittonum. Ed. David N. Dumville. Dover, N.H.: D.S. Brewer, 1985.

The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales. Ed. Patrick K. Ford. Berkley: University of California Press, 1977.

The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. Ed. Norris J. Lacy. New York: Garland Publishing, 1996.

The Poems of Taliesin.. Ed. Sir Ifor Williams; Trans. J.E. Caerwyn Williams. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1987.

Thelwall, John. The Fairy of the Lake. London: W.H. Parker, 1801.

Watkins, Vernon. The Collected Poems of Vernon Watkins. Ipswich, Suffolk: Golgonooza Press, 1986.

Williams, Charles. Taliesin Through Logres, and The Region of the Summer Stars. London, New York: Oxford University Press, 1954.

Williams, Gwyn. An Introduction to Welsh Poetry. London: Faber and Faber, 1953.

Williams, Ifor. Lectures on Early Welsh Poetry. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1954.

Wood, Carol Lloyd. An Overview of Welsh Poetry before the Norman Conquest. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1996.

Ystoria Taliesin. Ed. Patrick K. Ford. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. 1922.

Read Less