Read Less

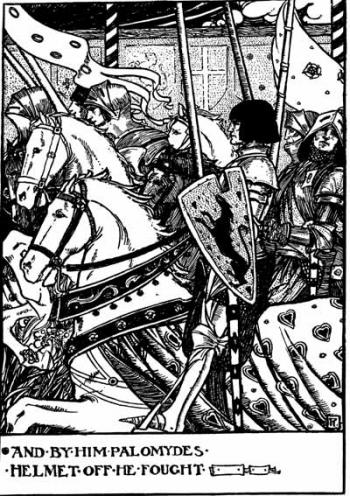

Sir Palamedes (var. Palomedes, Palomides, Palamede, and Palomydes) is a minor figure within the literary Arthurian tradition. Palomedes first appears in the 13th century. He is a Saracen knight of the Round Table; unbaptised and thus technically a pagan, but a true Christian at heart; a courtly lover who never achieves his desires; a figure of eternal chivalry in his pursuit of the Questing Beast. Palomedes appears to be the creation of the author(s) of the Old French Prose Tristan, a major narrative cycle begun around 1230 or 1235, possibly by a writer who refers to himself as "Luce del Gast," and completed sometime after 1240, possibly by a second writer who signed his work "Hélie de Boron"(Curtis xvi; Baumgartner 325). According to Baumgartner, the characters that appear to be original to the Prose Tristan are "comical and often misogynous insertions" that function as forms of "ironic counterpoint to the courtly ethic and chivalric behaviour normally observed by the protagonists" and they are usually "rehabilitated" later in the narrative (Baumgartner 332). Palomedes, however, does not require rehabilitation in the Prose Tristan; his character is falliable and he makes gross errors of behavior, but in this he is the reflection of Tristan, serving simultatneously as the superlative knight's foil and also as a standard against which to measure the great knight's prowess and accomplishment. Medieval and Renaissance retellings of the Tristan tradition, particularly those owing a strong textual debt to the French Prose Tristan, sustain Palomedes' dual role as negative contrast and positive comparison to Tristan.

The Palamedes of the Prose Tristan is a sympathetic character, a noble and valiant knight whose chivalric accomplishments are overshadowed by Tristan's great deeds. The narrative calls upon many characters, ranging from those already part of the Tristan tradition to those apparently created by the authors of the Prose Tristan, to function as literary doubles for Tristan himself. This doubling serves to expand the material but also, as Baumgartner observes, to interrogate the Arthurian tradition itself: "it is interesting to note how the Arthurian world is perceived by 'aliens' such as Tristan, Yseut, Mark and Kaherdin, or by the newcomers Dinadan and Palamedes, whose response is a mixture of admiration, criticism and hostility, but above all fascination" (Baumgartner 335). Tristan's acceptance of the rules of chivalry and courtly love is in Baumgartner's eyes "unthinking" (Baumgartner 335); perhaps a better perspective is that as one of the Arthurian world's greatest knights Tristan would not benefit from questioning the system that has placed him at the apex of status and accomplishment. Dinadan and other characters who "discuss, ridicule and reject the ways and customs which...have already become romance commonplaces" (Baumgartner 335) may question the system but are not in a position to do anything but reject it utterly, due to their lack of achievements and serious flaws. Characters like Palamedes are better equiped to meaningfully interrogate the system they find so fascinating, mediating between the extreme positions represented by Tristan and Dinadan. Perhaps a portion of the fascination the Palamedes of the Prose Tristan has held for critics and writers is due to his narrative positioning as both outsider and insider who is nevertheless effectual.

The parallels between Palamedes and Tristan make Palamedes an effective narrative device to question the conventions of the Arthurian world as the Tristan tradition perceives it, just as Tristan's resemblence to Lancelot grants him similar power within the context of the greater Arthurian tradition. Baumgartner notes that the "true originality of the Tristan...lies in the doubles the authors have created around Tristan, knights who are direct rivals in both love and chivalric prowess, such as Kaherdin and especially Palamedes" (335). Like Tristan, Palamedes falls deeply in love with Iseut: "He completely lost his heart to her; she pleased and attracted him so much that there was nothing in the world he would not have done to posssess her, even abandon his faith" (Curtis 45). Like Tristan, Palamedes' love for Iseut inspires his greatest acts of chivalry. Unlike Lancelot and Tristan, Palomedes never enjoys his beloved's affections and has no hope of ever achieving his desires. Palamedes' love for Iseut inspires his deeds, honorable and dishonorable alike, thus demonstrating the fine line a chivalrous knight must walk for love and for victory. Since he is aware of the near-impossibility of ever winning his beloved and yet continues to adore her despite her rejection of his love, Palamedes is arguably one of the few true courtly lovers in the Arthurian stories. In this sense, his love for her is the pure embodiment of the courtly ideal. Palamedes' love is never sullied by a physical consumation of the relationship; though consumation is arguably the ultimate goal of the courtly ethos, it is precisely Palamedes' failure as a courtly lover which provides him with an extra-textual moral superiority. Furthermore, the purity of Palamedes' love for Iseut is shown in sharp contrast to Tristan's own, particularly notable in the scene when Tristan first notices Palamedes:

Tristan had often looked at Iseut and she pleased him very much, but not in a way which made him fall in love with her. However, when he saw that Palamedes was so infatuated with Iseut that he said he would die if he did not have her, Tristan for his part said that Palamedes would certainly never have her if he could help it. Palamedes might be a dauntless knight, but there were others equally brave in the world. He himself, once he had completely recovered, would prove himself in one day as Palamedes had done a short while ago. (Curtis 46)

Palamedes' love brings him torment and challenge from Tristan, the rival whose relationship with Iseut is given legitimacy in the text. The rivalry between the two dauntless knights reflects Tristan's own rivalry with his own uncle and Iseut's husband; Mark and Tristan's rivalry will ultimately result in the deaths of the lovers, while that between Palamedes and Tristan ends in friendship because Palamedes, unlike Mark, is able to reconcile himself to Tristan's preeminence. As noted above, this acceptance is only possible because Palamedes is a worthy adversary, equal to Tristan himself, whereas Mark has little honor and fewer accomplishments. The relationship between Palamedes, Tristan, and Mark is oddly stable, reflecting different aspects of the central figure's character, demonstrating Tristan's good and bad qualities in the bedroom, on the battlefield, and in court.

The life of the Prose Tristan in languages other than Old French is particularly rich. The text--or rather, texts, since the collection of variant works known collectively as the Prose Tristan has survived in an astonishing eighty-two manuscripts or fragments, and perhaps yet more will be discovered (Baumgartner 329)--was translated and also reinterpreted repeatedly and enthusiastically into several continental vernacular languages, including Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese. These translations, adaptations, and revisions constituted a popular "consumer literature" of the Middle Ages (Baumgartner 329), and Palomedes was adapted along with the many other characters, adventures, and episodes which originated with the Prose Tristan. In some cultures, Tristan proved to be more popular than his counterpart Lancelot. For example, the Italian Arthurian tradition is particularly attached to Tristan. In an environment which privileges Tristan over all other knights, the characters who serve to demonstrate his greatness gain prominence, and indeed the Palomedes of the Tavola Ritonda becomes the mediator in the ever-popular debate amongst Arthurian knights (and audiences) as to who is the best knight, Lancelot or Tristan.

The Prose Tristan was also adapted into English by Sir Thomas Malory, author of the most influential English retelling of the Arthurian tradition, Le Morte Darthur. The adaptation is not complete, however, concluding immediately after Palomedes's baptism and decision to track the Questing Beast. Malory's choices in translating, adapting, and modifying the Tristan materials to suit his overall project are fascinating, and his Palomedes is a notably different character from the Palamedes of the Prose Tristan. Donald L. Hoffman notes that, unlike the scenario created in the Prose Tristan where Palamedes has established his name and reputation only to find them upset by the machinations of Tristan, Malory's character enters the narrative as an outsider, set up to fail in his quest for Iseut's love from the very beginning (49). Hoffman further notes that Palomedes's devotion to Iseut--"whan sir Palomydes saw La Beall Isode he was so ravysshed that he myght unnethe speke" (Malory 722)--is so great that her gaze has both positive and negative effects. Palomedes fights better under her eyes but his dishonorable, yet very human, attempt to manipulate the battlefield in his favor is laid bare to her panoptic view and thus, "the gaze that ennobles Palomides when he is honorable utterly destroys him when he is disgraced" (Hoffman 52). Despite many mistaken impressions, battles, and feuds, Malory's Palomedes and Tristan do eventually cement their fellowship and when Palomedes is christened Tristan stands as his godfather. After Tristan's death, Palomedes is one of the knights who side with and follow Launcelot to his French domain; consequently, he is enfeoffed. Thus, Palomedes ultimately redeems his past dishonorable tendencies and lives out his life in honor. Hoffman notes that in Malory, "the alien Other becomes the most accurate reflection of the Western medieval chivalric ideal" (54).

In the post-Malory Arthurian landscape, Palomedes has been gradually relegated to background status. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, eliminated Palomedes entirely from The Idylls of the King (1885), in large part due to the character's extremely strong ties to the Tristan tradition, a traditon of which Tennyson strongly disapproved. Tennyson could not entirely eliminate Tristan, who appears as an exemplar of the self-centered chivalry that degrades Arthur's great civilization and is then murdered by Mark while wooing Iseut. However, Tennyson could certainly eliminate the characters, Palomedes chief amongst them, who commonly serve as foils, and add depth, to the Tristan figure. T. H. White's series, unified under the title The Once and Future King (1958), mentions Tristan only in passing. White does devote significant attention to Palomedes; however, with his purpose as a foil to Tristan dissolved, the character becomes a buffoon. John Erskine's novel Tristan and Isolde: Restoring Palamede (1932 ) focuses on the character, but even the title is indicative of secondary role Palomedes plays within the tradition. Several minor poems, contemporaries to the aforementioned major works, have also focused on Palomedes; these poems largly concentrate on the melancholy aspects of the character, perpetually (and fruitlessly) seeking the Questing Beast or pining hopelessly for Iseut's love. William Fulford addresses twarted love and desire in "The Lament of Palomides" (1862); Frank Pearce Sturm's "The Questing Host" (1902) is particularly melancholic and reflective; and Aleister Crowley's long poem The High History of Good Sir Palamedes the Saracen Knight and of His Following of the Questing Beast (1912) is a unique interpretation, by a unique author, of Palomedes and his long quest. This last work, heavily influenced by Crowley's own mysticism, presents Palamedes as a divinely-chosen savior of the Arthurian court. For Crowley, Palamedes is a problematic seeker after knowledge, one whose crowning glory is not the achievment of his quest but his acknowledgement that man cannot ever know the divine mysteries represented by the Questing Beast.

The history of the literary Palomedes is long and varied, stretching from the 13th century to the present day. With the resurgence of academic and popular interest in the troubled hero, Palomedes' own popularity has begun to increase. There are many new novels, plays, and poems featuring the character; each presents a different aspect of the tradition, permitting Palomedes to change and adapt to the needs and demands of different audiences in different times.

BibliographyAllaire, Gloria, trans. Italian Literature I: Tristano Panciatichiano. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002.

Black Knight, The. Coloumbia Pictures. Dir. Tay Garnett. 85 min. 1954.

Brewer, Derek. "Palomides to Isolde." Seatonian Exercises and Other Verses. London: Unicorn Press, 2000.

Buchanan, Robert. "Joyous Garde" [stanza V]; "The Rescue" [stanza III]. Fragments of the Table Round. Glasgow: Thomas Murray and Son, 1859.

Carr, J. Comyns. Tristram & Iseult: A Drama In Four Acts. London: Duckworth, 1906.

Cooke, Brian Kennedy. The Quest of the Beast from Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur and Other Sources. London, E. Ward, 1957.

Crowley, Aleister. The High History of Good Sir Palamedes the Saracen Knight and of His Following of the Questing Beast. London: Wieland, 1911.

Curtis, Renée L., trans. The Romance of Tristan: The Thirteenth-Century Old French 'Prose Tristan'. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Denhard, Jared. "Palomides" a musical score. Arthur's Harp: Nine Pieces for Flute and Celtic Harp. Baltimore, MD: Jari A. Villaneuva, 1992.

Dobson, Austin. "Palomydes." At the Sign of the Lyre. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1885.

Edwards, Zachary. "Sir Palomides." Avilion and Other Poems. London: Chapman & Hall, 1907.

Erskine, John. Tristan and Isolde: Restoring Palamede. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1932.

Fulford, William. "The Lament of Palomides." Saul, A Dramatic Poem; Elizabeth, An Historical Ode; And Other Poems. London: Bell and Daldy, 1862. Pp. 189-193.

Gadzikowski, Paul. "On Sir Palomides." Bedivere's Round Table [electronic text].

Galasso, Michele. Il Tristano Corsiniano. Cassino: Le Fonti Ed., 1937.

Garcia y Robertson, R. "Three Heads for the High King." Ill. J. K. Potter. Weird Tales 51.1:1989. Pp. 74-96.

Jury, Charles Rischbieth. "Galahad." Galahad, Selenemia and poems. Adelaide: F. W. Preece, 1939.

Lovell, Gerald. "Palamides' Song"; "The Saracen and the Round Table." Arthurian Epitaphs and Other Verse. London: Mitre Press, 1976.

Lydgate, John. "A Complaynte of a Lovers Lyfe, or The Complaint of the Black Knight" [lines 330-43]. Chaucerian Dream Visions and Complaints. Ed. Dana M. Symons. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 2004.

Malory, Thomas. Works. Ed. Eugène Vinaver. London: Oxford University Press, 1954.

Morris, William. "Palomydes' Quest." The Collected Works. London: Longmans, Green, 1915.

---. "Sir Galahad, A Christmas Mystery." 'The Defence of Guenevere' and Other Poems. London: Bell and Daldy. 1859.

Owen, Francis. Tristan and Isolde: A Romance. Ilfracombe: Arthur H. Stockwell, 1964.

Pinsky, Robert. "Jesus and Isolt." The Want Bone. New York: Ecco Press, 1990. Pp. 32-40.

Powys, J[ohn] C[owper]. Maiden Castle. New York: Simon and Schuster,1936.

Prince, Ælian [Frank Carr]. "Of Joyous Gard"; "Of Palomide Famous Knight Of King Arthur's Round Table". London: E. W. Allen, 1890.

Psaki, Regina, trans. Italian Literature II: Tristano Riccardiano. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2006.

Roberts, Theodore Goodridge. "Sir Palomides' Lament." The Leather Bottle. Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1934. P. 77.

Shaver, Anne, trans. and ed. Tristan and the Round Table: A Translation of La Tavola Ritonda. Ed. Annette Cash; Illus. Catherine M. Hiller. Binghamton, NY: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, State University of New York at Binghamton, 1983.

Snyder, Maryanne K. "Palimedes to Isolde." Quondam et Futurus 3:1992. P. 37.

Stewart, R[osalind] H. "The Perfect Stranger" in The Chronicles of the Round Table, ed. Mike Ashley. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1997.

Sturm, Frank Pearce. "Palomede Remembers the Quest" Journal of Bon-Accord 35:26, 1903.

---. "The Questing Host." Journal of Bon-Accord 32:19, 1902.

Swinburne, Algernon Charles. "Tristram of Lyonesse." Tristram of Lyonesse and Other Poems. London: Chatto and Windus, 1882.

Taggart, Marion Ames. "The Secret of Sir Dinadan." Catholic World 60:350, 1894. Pp.248-249.

Taylor, Keith. Bard. New York: Ace Books, 1981.

---. Bard IV: Ravens' Gathering. New York, Ace Books 1990.

Thompson, Raymond H. "Interview With Michael Coney." Taliesin's Successors: Interviews With Authors Of Modern Arthurian Literature. The Camelot Project. [electronic text]

Van Dyke, Henry. The Mill. 1902. Great short works of Henry van Dyke. New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

White, T. H. The Once and Future King. New York: Putnam, 1958.

Williams, Charles. "A Song of Palomides [revised as 'Colophon made by the Copyist']"; "Palomides' Song of Iseult." Heroes and Kings. London: The Sylvan Press, 1930.

---. "The Coming of Palomides"; "Palomides Before his Christening"; "The Death of Palomides." Taliessin through Logres. London: Oxford University Press, 1939.

Wilson, John Grosvenor. "Sir Palamides." Lyrics of Life. New York: Caxton Book Concern, 1886.

Read Less