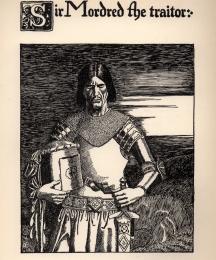

Mordred (Modred, Medrawd, or Medraut) has become the quintessential traitorous villain in the Arthurian tradition. According to the majority of texts, he is Arthur's bastard son by his half-sister Morgause, the wife of King Lot. This incestuous begetting, alternately an innocent mistake on the part of both parties, as the French Vulgate portrays it, or a perverted seduction on Morgause's part, as in the film

Excalibur, can in part explain why Mordred's character and sense of loyalty is so twisted. However, his reputation has not always been quite so bad.

In Welsh tradition there is no hint that Mordred is a dishonest traitor. The Annales Cambriae records the battle of Camlann, "in which Arthur and Medraut fell" in the year 537, and includes no details describing whether the two fought each other, whether they were related, or what the circumstances of the battle were. In another Welsh text, the Dream of Rhonabwy, we learn that bad blood erupts in an already tense diplomatic relationship between Arthur and his nephew Medrawd because of a messenger, Iddawg, the "Churn of Britain" who is eager for battle. Iddawg delivers Arthur's kind request for peace in the "rudest possible way," and thus causes the war.

In the Historia Regnum Brittonum of 1136, Geoffrey of Monmouth first makes Mordred the traitor causing the downfall of Camelot and the death of Arthur. The villain is as yet Arthur's nephew, the youngest son of King Lot and Anna, King Arthur's half-sister. Interestingly, he fills the adulterous role with Guinevere that Lancelot will eventually play. While Arthur is away fighting the Roman general Lucius, Mordred marries Guinevere and attempts to claim Arthur's

...

Read More

Read Less

Mordred (Modred, Medrawd, or Medraut) has become the quintessential traitorous villain in the Arthurian tradition. According to the majority of texts, he is Arthur's bastard son by his half-sister Morgause, the wife of King Lot. This incestuous begetting, alternately an innocent mistake on the part of both parties, as the French Vulgate portrays it, or a perverted seduction on Morgause's part, as in the film

Excalibur, can in part explain why Mordred's character and sense of loyalty is so twisted. However, his reputation has not always been quite so bad.

In Welsh tradition there is no hint that Mordred is a dishonest traitor. The Annales Cambriae records the battle of Camlann, "in which Arthur and Medraut fell" in the year 537, and includes no details describing whether the two fought each other, whether they were related, or what the circumstances of the battle were. In another Welsh text, the Dream of Rhonabwy, we learn that bad blood erupts in an already tense diplomatic relationship between Arthur and his nephew Medrawd because of a messenger, Iddawg, the "Churn of Britain" who is eager for battle. Iddawg delivers Arthur's kind request for peace in the "rudest possible way," and thus causes the war.

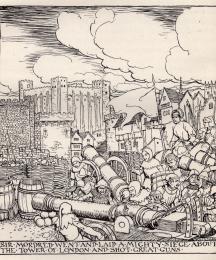

In the Historia Regnum Brittonum of 1136, Geoffrey of Monmouth first makes Mordred the traitor causing the downfall of Camelot and the death of Arthur. The villain is as yet Arthur's nephew, the youngest son of King Lot and Anna, King Arthur's half-sister. Interestingly, he fills the adulterous role with Guinevere that Lancelot will eventually play. While Arthur is away fighting the Roman general Lucius, Mordred marries Guinevere and attempts to claim Arthur's throne as his own. Arthur returns from France to fight a series of battles. The tragic last battle, called Camlann, takes place at the River Cambula in Cornwall (the present-day Camel River). Medieval French authors first introduce the incest factor. In the Vulgate cycle, the massive collection of French Arthurian texts that served as one of Sir Thomas Malory's sources for the Morte D'Arthur, two conflicting stories of Mordred's incestuous conception appear. In one, Arthur and his anonymous sister, the beautiful wife of King Lot of Orkney, commit incest unknowingly, discovering afterwards that they are brother and sister. In another the woman has been the object of Arthur's affections, and in a scene strangely reminiscent of the conception of Arthur himself, is deceived by Arthur into thinking that he is her husband, Lot. The result of this morally ambiguous union is Mordred, who, the Vulgate authors relate, "would have had a very handsome face if his demeanor had not been so wicked" (Lancelot-Grail, ed. and trans. Norris Lacy, vol. 3, p. 108).

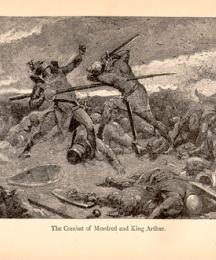

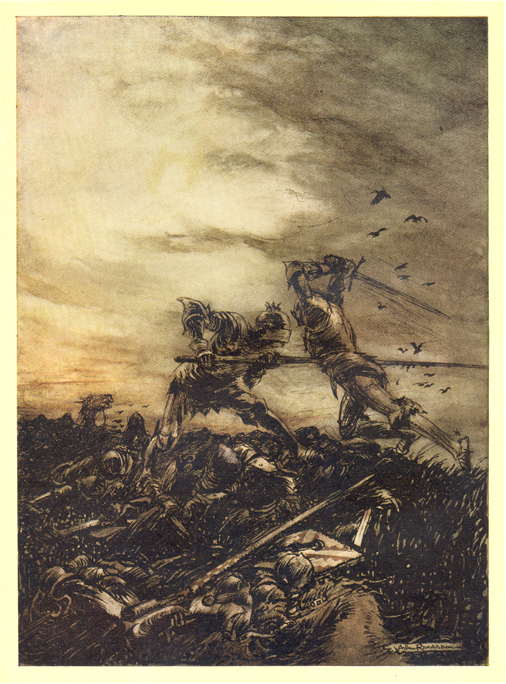

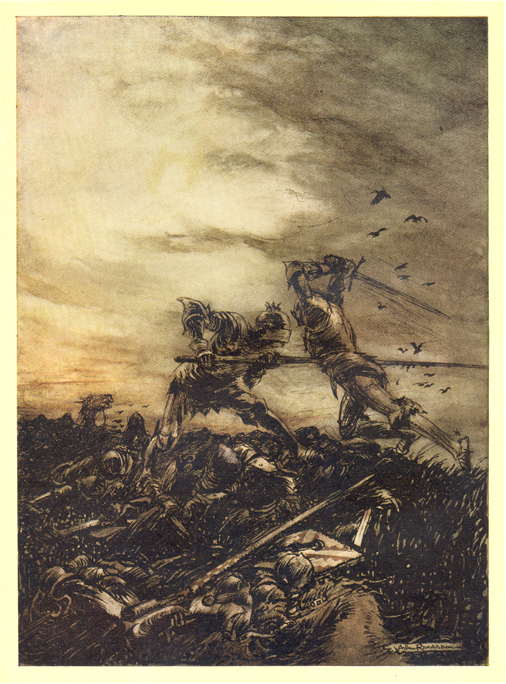

Thomas Malory's account of Mordred's treachery is the most well-known and influential version of the story. Malory popularizes an episode from the Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin, commonly called the "May-Day Massacre," in which Arthur heeds Merlin's prophecy that the child who will cause the downfall of his kingdom will be born on May-Day. He collects all of the children born on the first of May throughout his kingdom, some only four weeks old, places them in a ship and sets it adrift at sea with the hope that the fatal child will die. His plan fails, however; the ship breaks up on the rocks, killing all of its occupants except for Mordred, who is rescued and fostered until age fourteen. Throughout the text he appears now and again in tournaments but does not figure importantly until towards the end, when he joins Agravain in the plot against Lancelot and Guinevere. Narrative details emphasized by Malory figure importantly in the later adaptations of his character; for example, he only manages to kill Sir Lamorak by stabbing him in the back, and in the fight outside the Queen's bedchamber, he only survives by running away from Lancelot. In the ensuing strife after Lancelot rescues Guinevere from being burned at the stake, Mordred attempts to take over the kingdom while Arthur and Gawain are away at the Siege of Benwick. Typically Malorian detail follows in the description of the fatal wounding of Arthur and the death of his treacherous son: "And whan sir Mordred felte that he had hys dethys wounde he threste himselff with the myght that he had upp to the burre of kyng Arthurs speare, and ryght so he smote hys fadir, kynge Arthure. . ." (Malory, ed. Vinaver, p. 1237). For an excellently gruesome illustration of this final fight, see Arthur Rackham's "How Mordred Was Slain by Arthur . . ." (left).

Thomas Malory's account of Mordred's treachery is the most well-known and influential version of the story. Malory popularizes an episode from the Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin, commonly called the "May-Day Massacre," in which Arthur heeds Merlin's prophecy that the child who will cause the downfall of his kingdom will be born on May-Day. He collects all of the children born on the first of May throughout his kingdom, some only four weeks old, places them in a ship and sets it adrift at sea with the hope that the fatal child will die. His plan fails, however; the ship breaks up on the rocks, killing all of its occupants except for Mordred, who is rescued and fostered until age fourteen. Throughout the text he appears now and again in tournaments but does not figure importantly until towards the end, when he joins Agravain in the plot against Lancelot and Guinevere. Narrative details emphasized by Malory figure importantly in the later adaptations of his character; for example, he only manages to kill Sir Lamorak by stabbing him in the back, and in the fight outside the Queen's bedchamber, he only survives by running away from Lancelot. In the ensuing strife after Lancelot rescues Guinevere from being burned at the stake, Mordred attempts to take over the kingdom while Arthur and Gawain are away at the Siege of Benwick. Typically Malorian detail follows in the description of the fatal wounding of Arthur and the death of his treacherous son: "And whan sir Mordred felte that he had hys dethys wounde he threste himselff with the myght that he had upp to the burre of kyng Arthurs speare, and ryght so he smote hys fadir, kynge Arthure. . ." (Malory, ed. Vinaver, p. 1237). For an excellently gruesome illustration of this final fight, see Arthur Rackham's "How Mordred Was Slain by Arthur . . ." (left).

This tradition of a treacherous and twisted character, present in the minor yet unsavory details Malory provides, work as a foundation from which modern authors represent Mordred. Edwin Arlington Robinson's "Modred, a Fragment" is a masterful and intensely psychological portrayal of villainy. Robinson's Modred is brilliantly manipulative and eloquent, and chillingly reminds us more of Milton's Satan than of the Mordred in Geoffrey's Historia and other chronicles. In fact it is here we must realize the drastic change between villain portrayals when we move from chronicles to romances and novels. Villainy takes on a more psychological aspect; Mordred is suddenly a full-bodied character with motivations, instead of a catalyst with a name.

In The Once and Future King, possibly the most widely read twentieth-century depiction of the Arthurian Legend, T.H. White paints Mordred as a court fop, the herald of outrageous new fashions and modern ideas, and, most importantly, the victim of his depraved mother's moral training. White describes how "now that [Morgause] was dead, [Mordred] had become her grave. She existed in him like the vampire" (White, The Once and Future King [London: Harper Smith, 1996], p.666). While he nurses his grudge against his father for trying to kill him in infancy, White's Mordred manipulates his brothers, lurks behind doors while eavesdropping, and eventually becomes a mad, black-clad, sinister version of Hamlet. While White's Mordred is a satisfyingly complex and thoroughly evil villain, later authors (most notably Mary Stewart, in The Wicked Day) have tried to create a more sympathetic character.

BibliographyKorrel, Peter. An Arthurian Triangle: A Study of the Origin, Development and Characterization of Arthur, Guinevere and Modred. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1984.

Read Less