Lanval or Launfal, while not one of the famous knights like Lancelot, Gawain, Tristan, and Perceval, who dominate medieval romance, was nevertheless internationally known. In the latter half of the twelfth century, Marie de France wrote a Breton lay called

Lanval. Breton lay is a term that designates a short verse tale claiming to be based on a Celtic theme as sung by Breton harpers. Marie’s Lanval is a knight who receives no lands or gifts from King Arthur and thus slips into poverty. In the countryside, he encounters a fairy maiden who gives him her love and great wealth, which he distributes liberally to others. The maiden’s only condition for her love is that it never be revealed, lest he lose her forever. Lanval abides by this condition until he is propositioned by Arthur’s queen. He refuses her by saying he will not betray Arthur; but when she charges that he is ‘not interested in women’ and has ‘taken [his] pleasure’ with the young men he trains, he retaliates by declaring that he loves a lady ‘whose poorest serving girl is more worthy’ than the queen (38). In her anger, she accuses him of having propositioned her and then of insulting her. When he is tried, Arthur’s barons demand that he produce his beloved to prove his claim about her beauty. At the last moment, the fairy maiden rides up and vouches for Lanval’s account of his encounter with the queen. Lanval, acquitted, leaps on his lady’s horse, and they ride off to Avalon.

In the 13

th century, the lays of Marie and other anonymous lays were translated as part of the initiative of King Hákon Hákonarson of Norway. Twenty-one lays in all comprise the Norse lays, called the

Strengleikar....

Read More

Read Less

Lanval or Launfal, while not one of the famous knights like Lancelot, Gawain, Tristan, and Perceval, who dominate medieval romance, was nevertheless internationally known. In the latter half of the twelfth century, Marie de France wrote a Breton lay called

Lanval. Breton lay is a term that designates a short verse tale claiming to be based on a Celtic theme as sung by Breton harpers. Marie’s Lanval is a knight who receives no lands or gifts from King Arthur and thus slips into poverty. In the countryside, he encounters a fairy maiden who gives him her love and great wealth, which he distributes liberally to others. The maiden’s only condition for her love is that it never be revealed, lest he lose her forever. Lanval abides by this condition until he is propositioned by Arthur’s queen. He refuses her by saying he will not betray Arthur; but when she charges that he is ‘not interested in women’ and has ‘taken [his] pleasure’ with the young men he trains, he retaliates by declaring that he loves a lady ‘whose poorest serving girl is more worthy’ than the queen (38). In her anger, she accuses him of having propositioned her and then of insulting her. When he is tried, Arthur’s barons demand that he produce his beloved to prove his claim about her beauty. At the last moment, the fairy maiden rides up and vouches for Lanval’s account of his encounter with the queen. Lanval, acquitted, leaps on his lady’s horse, and they ride off to Avalon.

In the 13

th century, the lays of Marie and other anonymous lays were translated as part of the initiative of King Hákon Hákonarson of Norway. Twenty-one lays in all comprise the Norse lays, called the

Strengleikar.

Lanval was translated into Norse as

Janual (or

Januals ljóđ), a fairly close rendition of Marie’s lay with occasional variations and stylistic traits typical of the Norse adaptations of romance literature.

Marie’s lay is believed to have been translated into Middle English in a version now lost. This translation influenced the Middle English poem

Sir Landevale (written in the first half of the fourteenth century), which in turn influenced Thomas Chestre’s late fourteenth-century

Sir Launfal. The lost translation is believed also to have influenced two sixteenth-century English versions,

Sir Lambewell and the fragmentary

Sir Lamwell, a rendition of the tale with Scottish dialectical traits.

While

Sir Landevale is a fairly close translation of its original and serves as a source for Thomas Chestre’s

Sir Launfal, the latter poem also adds a good bit of material not in the earlier versions. It includes scenes in which the mayor of the town fails to show hospitality to Launfal because of his poverty. It adds a demonstration of Launfal’s prowess when he is challenged by a knight named Valentyne, who is said to be fifteen feet tall and whom he kills in battle. It also expands on the picture of Gwennere (Guinevere) as an unfaithful, proud, vengeful woman. Said to be the daughter of King Ryon of Ireland, Gwennere proclaims that her eyes should be put out if Launfal can produce a fairer woman. When his beloved, here named Tryamour, arrives and all agree that she is indeed fairer, the fairy woman blows on her such a breath that Gwennere is blind ever after.

After the Middle Ages, Lanval/Launfal appears in a number of works. Launfal was the protagonist in t

James Russell Lowell’s popular poem

The Vision of Sir Launfal. In Lowell's poem, Launfal is a knight from a time other than that of Arthur, but he also seeks the Grail. Nowhere else in Arthurian legend does Launfal seek the Grail. Marie de France’s

Lanval and the Middle English

Sir Launfal have no mention of a Grail quest, though in each, the title character’s generosity is crucial to the plot; and it is precisely generosity, or the Christianized version of the virtue, charity, that Lowell’s Launfal must acquire. Although initially a haughty man who only gives scornfully to beggars, he is taught by a dream vision that charity is the true meaning of the Grail. He then acquires the traditional trait of generosity, opening up his castle and sharing his wealth with all.

Edward George Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873), who wrote an epic poem about King Arthur, also wrote a short poem called “The Fairy Bride” (1853) which tells the story of a knight named Elvar, who loses his fairy lover when he breaks his pledge never to speak of her. Though his Genevra has none of the vices of her medieval counterpart, Bulwer-Lytton’s poem is no doubt a reworking of the traditional tale.

Lanval is also the subject of the play

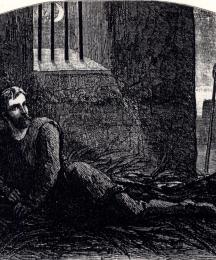

Lanval (1908) by British author T. E. Ellis, which combines elements from the chronicle tradition and from other romances with the traditional Lanval story. The play dramatizes Lanval’s encounter with the fairy Triamour and, after a stay in her realm, his desire to return to the world. There he is favored by his lover until he reveals her existence. When he is condemned and is banished, Triamour does not appear to save him from the judgment; but she does reappear as he wanders disgraced in the woods to ask sarcastically if he is content ‘With all the honours, merits and rewards’ the world has given him. Ultimately, she says she will give him ‘the kindest gift of all— / Release’ from life (126, 129). He dies without the vindication that he receives in the medieval tales and without any disclosure of the queen’s guilt.

The film

Sir Lanval was produced by the Chagford Filmmaking Group, a nonprofit organization which defines its mission as making films of British fairytales. Their website says that they “simply wish to tell the magical stories rooted in the British landscape, stories that are part of our heritage.” The film is based on Marie’s

Lanval but with some details from the Middle English

Sir Launfal and with some original touches. For example, the name Triamour for the fairy lover comes from

Sir Launfal. So too does the purse given to Lanval by his lover, a purse that never runs out of gold. The film also adds a humorous scene in which the jealous Queen banishes anyone to whom Lanval shows kindness—including a young woman, an old woman, and even a donkey. One of the most significant variations from the medieval sources is the ending of the film—which is less definitive than that of Marie’s

Lanval.

BibliographyBliss, A. J. “The Hero’s Name in the Middle English Versions of Lanval.” Medium Ævum 27 (1958): 80-85.

Eccles, Jacqueline. “Feminist Criticism and the Lay of Lanval: A Reply.” Romance Notes 38.3 (Spring 1998): 281-85.

Ireland, Patrick John. “The Narrative Unity of the Lanval of Marie de France.” Studies in Philology 74 (1977): 130-45.

Jurasinski, Stefan. “Treason and the Charge of Sodomy in the Lai de Lanval.” 54.4 (Fall 2007): 290-302.

Kinoshita, Sharon. “‘Cherchez la femme’: Feminist Criticism and Marie de France’s Lay of Lanval.” Romance Notes 34.3 (Spring 1994): 263-73.

Lupack, Alan, and Barbara Tepa Lupack. “Arthurian Literature in America before Twain.” Chapter 1 of King Arthur in America. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1999. Pp. 1-34, especially pp. 10-15.

O’Sharkey, Eithne M. “The Identity of the Fairy Mistress in Marie de France’s Lai de Lanval.” Trivium 6 (1971): 17-25.

Poe, Elizabeth Wilson. “Love in the Afternoon: Courtly Play in the Lai de Lanval.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 84.3 (1983): 301-10.

Ramke, Kelly. “Re-Writing Agency: The Masculinization of Marie de France’s Lai de Lanval in Two Middle English ‘Translations.’” Mediaevalia 20.2 (20050: 221-41.

Seaman, Myra. "Thomas Chestre’s Sir Launfal and the Englishing of Medieval Romance." Medieval Perspectives 15 (2000): 105-19.

Stokoe, William C., Jr. “The Sources of Sir Launfal: Lanval and Graelent,” PMLA 63.2 (1948): 392-404.

Walkley, M. J. “The Critics and Lanval.” New Zealand Journal of French Studies 4.1 (May 1983): 5-23.

Williams, Elizabeth. “Lanval and Sir Landevale: A Medieval Translator and His Methods.” Leeds Studies in English n.s. 3 (1969): 85-99.

Versions of the Launfal/Lanval Story:

Marie de France. Sir Lanval. A Breton lay from the latter half of the twelfth century'

Marie de France. Lanval. In Lais. Ed. Alfred Ewert. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1960. 58-74.

Marie de France. Lanval. Trans. Norris J. Lacy. In Arthurian Literature by Women. Ed. Alan Lupack and Barbara Tepa Lupack. New York: Garland, 1999. 35-42.

Janual, an Old Norse translation of Marie’s Lanval, one of twenty-one lays known as Strengleikar written by Marie and other anonymous authors and translated as part of the initiative of King Hákon Hákonarson of Norway (who reigned from 1217 to 1263).

Janual. Ed. and Trans. Robert Cook. In Norse Romance I. The Tristan Legend. Arthurian Archives III. Ed. Marianne E. Kalinke. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1999. 10-22.

Sir Landevale, a Middle English verse adaptation of Marie’s lay from the first half of the fourteenth century, perhaps through the intermediary of a lost Middle English translation of Lanval:

Sir Landevale. In Chestre, Thomas. Sir Launfal. Ed. A. J. Bliss. London: Thomas Nelson, 1960. 105-28.

Sir Launfal, a Middle English verse romance from the late fourteenth century.

Chestre, Thomas. Sir Launfal. In The Middle English Breton Lys. Ed. Anne Laskaya and Eve Salisbury. Kalamazoo, MI Medieval Institute Publications, 1993.

Sir Lambewell, a sixteenth-century English lay probably derived from the lost Middle English translation of Marie’s Lanval.

Sir Lambewell. In Bishop Percy’s Folio Manuscript: Ballads and Romances. 3 vols. Ed. John W. Hales and Frederick J. Furnivall. London: N. Trübner, 1867. 1: 142-64.

Sir Lamwell, a sixteenth-century lay, derived from the lost Middle English translation of Marie’s Lanval, with Scottish dialectical traits.

Sir Lamwell. In Captain Cox, His Ballads and Books; or, Robert Laneham’s Letter. Ed. F. J. Furnivall. London: For the Ballad Society, 1871. xxx-xxxiii.

James Russell Lowell’s The Vision of Sir Launfal, an American poem that turns Launfal into a seeker of the Grail who learns that charity is the true Grail and thus transforms Launfal’s traditional generosity into the quality that makes him a Grail knight.

Lowell, James Russell. The Vision of Sir Launfal. Cambridge: George Nichols, 1848.

“The Fairy Bride” (1853), a poem by Edward George Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873), tells the story of a knight named Elvar, who loses his fairy lover when he breaks his pledge never to speak of her.

Bulwer-Lytton, Edward. ‘The Fairy Bride.’ In Dramas and Poems. 1853; rpt. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1874. 270-84.

Lanval (1908), a play by British author T. E. Ellis, combines elements from the chronicle tradition and from other romances with the traditional Lanval story. The play dramatizes Lanval’s encounter with the fairy Triamour and, after a stay in her realm, his desire to return to the world. There he is favored by his lover until he reveals her existence. Triamour does not appear to save him from the judgment; but she does reappear as he wanders disgraced in the woods to give him ‘the kindest gift of all— / Release’ from life (126, 129). He dies without the vindication that he receives in the medieval tales and without any disclosure of the queen’s guilt.

Ellis, T. E. Lanval: A Drama in Four Acts. London: Privately printed by John & Ed. Bumpus, 1908.

Sir Lanval, a film based on Marie’s Lanval but with some details from the Middle English Sir Launfal and some original touches.

Sir Lanval. Dir. Elizabeth-Jane Baldry. Chagford Filmmaking Group, 2011.

Read Less