Read Less

Sir Galahad, the son of

Lancelot and Elaine of Corbenic, is best known as the knight who achieves the

Holy Grail. When Galahad appears, he is the chief Grail knight; in the French and English traditions, he replaces

Perceval in this role. Galahad first appears in the thirteenth-century Vulgate Cycle. The opening part of the Cycle, the

Estoire del saint Graal, first mentions Galahad; it predicts his birth and his eventual achievement of the Grail. According to this section of the text, Galahad is ninth in the line of Nascien, who was baptized by Josephus, son of Joseph of Arimathea. This lineage connects Galahad to those who are said to have brought Christianity (and the Grail itself) to Britain. A later section,

La Queste del saint Graal, recounts his adventures on the quest, which leads from Arthur's court to the city of Sarras, the earthly home of the Grail, and the place where Galahad dies while contemplating the Grail. Stories of Galahad's adventures are exceptionally consistent; the account of Galahad's quest from Malory’s

Morte d'Arthur, "The Noble Tale of the Sankgreal," draws on the major events from the Vulgate Cycle. Malory preserves the prophesy and foretelling that surround Galahad; within the Grail Quest, hermits and other religious figures continually appear to interpret dreams and anticipate upcoming events. Galahad’s birth and achievements are foretold in both the Vulgate Cycle and in Malory; this gives the entire Grail Quest a sense of inevitability.

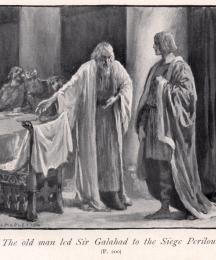

In both Malory and

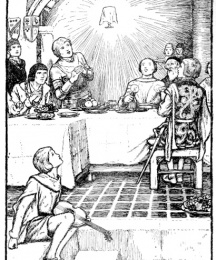

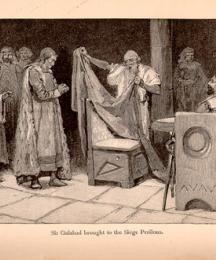

La Queste del saint Graal, Galahad is knighted by Lancelot at a convent in the woods. At the feast of Pentecost, he arrives in Camelot, where he is able to sit in the

Siege Perilous, an act which demonstrates that he is the knight who will achieve the Grail. After the Grail appears at the Pentecost feast, the knights vow to spend a year and a day seeking the Grail. Galahad sets out on the quest without a shield. Accompanied by King Bademagu, he stops at an abbey, and they learn that the abbey houses a white shield marked with the blood of Galahad’s ancestor, Josephus. When Bademagu takes the shield from the abbey, a mysterious white knight appears and knocks him from his horse; the white knight’s squire then brings the shield to Galahad. The shield is meant exclusively for Galahad and will protect only him. On his travels, he reaches the Castle of Maidens, where seven cruel knights hold a duke’s daughter and all who pass through the region captive; he restores order by defeating the evil knights in combat and making the knights native to the country swear fealty to the duke’s daughter. However, Galahad does not kill the seven cruel knights. (The seven knights are killed the next day when several other Round Table knights encounter them.) After leaving the Castle, Galahad travels through the Waste Forest until he reaches the sea. There, he is reunited with fellow Grail knights Perceval and Bors. The three knights travel together to Logres, where they and nine foreign knights experience a mass and have a vision of the Grail. At this mass, Christ himself appears to Galahad and tells him that the Grail is not sufficiently respected in the land and that Galahad will see the Grail more openly when he reaches Sarras. Galahad, Percival, and Bors then journey to Sarras with the Grail on a mysterious ship. After some time in Sarras, Galahad prays for death and dies while contemplating the Grail.

Both texts explain Galahad’s birth out of wedlock; Lancelot is magically tricked into sleeping with Elaine (who is called Amite or “the rich Fisher King’s daughter” in the Vulgate Cycle), and Galahad is the result of that union. In spite of the circumstances of his birth, the texts emphasize Galahad’s inherent virtue. The narrator in the

Estoire del saint Graal acknowledges Galahad's problematic conception (without explicitly identifying him as a bastard child), but praises him on the grounds of his worthy lineage, good life, and good purpose. In the Vulgate Cycle, he is often referred to simply as the "Good Knight" (

Lancelot-Grail 4:6, 4:20) or the "worthy man" (

L-G 4:5). Malory seems even more comfortable with Galahad’s bastard status; in the

Queste, Galahad demonstrates embarrassment at his paternity in a conversation with Guinevere, but Malory leaves this conversation out of his version (Watson 58-59). Instead, when Guinevere is asked by one of her ladies if Galahad should rightly be such a good knight, she claims that "he ys of all partyes comyn of the beste knyghtes of the world, and of the highest lynage" (Malory 502). In Malory’s text, Galahad’s status as a bastard child does not detract from his prestigious lineage in the slightest; rather, the quality of his parents and his own inherent virtue outweigh the circumstances of his birth. Descriptions of Galahad inevitably remark on his youth and beauty as defining characteristics, and he is often immediately recognizable as Lancelot's son. In the

Queste when Lancelot first encounters Galahad, Lancelot observes that Galahad "was endowed with exceptional beauty" (

L-G 4:3). Similarly, upon Galahad’s arrival at Arthur’s court, a young man describes Galahad to Guinevere as "one of the world’s most handsome knights" (

L-G 4:6).

Galahad's virginity is the key to his perfection and therefore the key to his success in the Grail Quest. Galahad’s quest has certain parallels with hagiographic literature, notably stories of St. John the Evangelist; these similarities appear in the healings and “miracles” Galahad performs, as well as in his virginity (O’Malley 40). Galahad’s saintliness makes him the knight who most fully achieves the Grail, and this status distinguishes Galahad from his Round Table peers in potentially problematic ways. Galahad’s successes simultaneously confer honor on the Round Table and demonstrate the weakness of his fellow knights, who often fail where Galahad succeeds (Armstrong 32).

Galahad's perfection, especially his virginity, makes him both admirable and irksome to modern adaptors of the Grail story. Malory’s version inspired many retellings of Galahad’s adventures, the best known of which is by Tennyson. The

Idylls of the King preserves Galahad as the chief Grail Knight. As a result, he is a figure of mythic status even to Perceval, a fellow Grail Knight. Galahad’s visions of the Grail separate him from the rest of his Round Table companions, such as Lancelot, who declares upon his return to Camelot that "’this Quest was not for me’" (849). Similarly, Tennyson's

"Sir Galahad" depicts a heavenly, peerless knight who famously claims that "My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure" (ll. 3-4). Tennyson presents purity as a source of strength, an image of Galahad that was exceptionally popular with Victorian audiences (Mancoff,

Return, 123). Boldly persistent in his quest, Galahad consistently moves forward toward his goal. Perhaps due to this image of the tireless, virtuous knight, Tennyson’s poems are sometimes used in texts which associate Galahad with war, and Galahad was invoked as a symbol of patriotic Englishness during World War I (Mancoff,

Return, 126). James Burns’s

Sir Galahad: A Call to the Heroic promotes Galahad as the righteous Christian soldier whose behavior the young men of Britain should emulate. This use of Galahad appears not only in literature, but also in art. Stained glass windows depicting Galahad were often created (from roughly 1900 through 1930) to memorialize the deaths of young men, especially young men killed during the war. Stained glass depictions of Galahad were also common in public schools, reinforcing Galahad as an idealized role model for young men. Such depictions often incorporate lines from Tennyson or Malory and thus connect the image to a specific text (Poulson 112-114). One such window, in St. Paul’s Church, Fairlie, was commissioned by Sir James and Lady Dobbie in 1919 to commemorate the death of their son Alexander. Along the bottom, the window quotes Tennyson’s “The Holy Grail”:

So now the Holy Thing is here again

Among us, brother, fast thou too and pray,

And tell thy brother knights to fast and pray,

That so perchance the vision may be seen

By thee and those, and all the world be healed. (ll. 124-29) (Poulson 110)

Artists appropriated this depiction of Galahad as the holy warrior to commemorate the young men who had been exhorted to follow Galahad’s example.

Tennyson’s unwavering Galahad reappears in later poetic works. Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s "The Terrible Test" positions Galahad as transcendent from the perspective of modern readers; she writes that "We read-- and smile; no man thou wast; / No human pulses thine could be" (ll. 13-14). Phelps, like Tennyson, presents Galahad as unaffected by the worldly temptations which trouble his fellow knights. William Morris, in contrast, presents a troubled Galahad who takes his comfort from Christ. Galahad suffers discouragement in Morris’s "Sir Galahad, A Christmas Mystery," in which he reflects that "night after night you sit / Holding the bridle like a man of stone, / Dismal, unfriended: what thing comes of it?" (ll. 22-24). Though Morris’s Galahad moves forward in his quest, he expresses loneliness and melancholy unknown to Tennyson’s immutable Galahad. This humanized portrayal of Galahad is typical of Morris’ works; he depicts Arthurian heroes as fallible human beings rather than mythic ideals. While he retains the uncorrupted, perfect Galahad, Morris presents a man who needs to be refreshed rather than Tennyson’s unshakable knight who never experiences temptation (Mancoff, Revival, 163).

Galahad’s superhuman traits are not always depicted in a positive light. T. H. White's The Once and Future King emphasizes Galahad’s perfection by way of distancing him from the rest of the court. In White's retelling of Malory, Galahad's adventures on the Quest are retold by other Knights of the Round Table as they return to Camelot. The various other knights (particularly Gawaine) question Galahad's virginity and consider him uppity, superior, and socially deficient (489). Only Lancelot defends Galahad, and Lancelot’s defense itself may be perceived as unflattering. He claims that Galahad is inhuman and therefore falls outside the confines of social manners (495).

Several modernizations drastically re-imagine Galahad’s life, notably his origins; as a result, these modern Galahads and their adventures look very different from their medieval counterpart. John Erskine’s novel Galahad: Enough of his Life to Explain His Reputation (1926) revises Galahad’s life, especially his education, in order to rationalize Galahad’s unique personality. The novel depicts a spoiled, violent young Galahad who is taught to be a knight by his father, Lancelot. Galahad eventually comes to Camelot, where Guinevere seeks to transform him into a new type of knight who will be single-mindedly devoted to virtue. However, upon discovering the queen’s affair with his father, Galahad abandons the court because her behavior does not coincide with her teachings. The text leaves Galahad’s adventures open-ended after he leaves Camelot. Rather than sending Galahad on the Grail Quest, the novel traces his development into a character likely to be associated with such a quest.

Galahad’s birth is retold in Richard Hovey’s play, The Birth of Galahad (1898). In Hovey’s play, Galahad is the son of Lancelot and Guinevere; this change is unique to Hovey’s version. In Hovey’s wife’s introduction to the published fragments of Hovey’s unfinished plays, she writes that “Galahad’s pure soul grew as the form of blessing which only ‘the miracle,’ the mystic love, can bring to earth. It belongs to the realms that are above the laws of social order” (qtd. in Lupack, Arthur in America, 106). In this context, the perfect knight becomes the child of the ideal lovers; the purity of Lancelot and Guinevere’s love outweighs the adulterous (and thus socially unacceptable) nature of their relationship. Hovey, Erskine and White re-envision Galahad to comment on social expectations and to make him more interesting to modern readers.

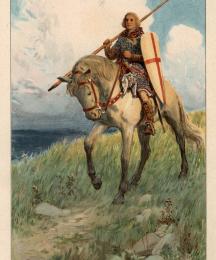

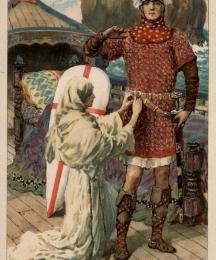

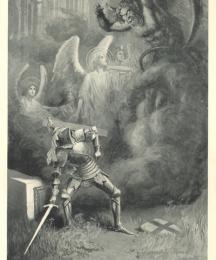

In addition to his popularity in literature, Galahad has been a popular subject of visual representation. Galahad was often used to represent "inspired attacks on evil" (Whitaker 236). As in the poetry, many paintings of Galahad emphasize his perfection and purity; one famous example is "Sir Galahad" (1862) by George Frederic Watts (1817-1904). Watts’s Galahad is depicted in profile as he gazes forward and leads his horse; his helmet hangs behind him so that his curly hair and youthful, idealized facial features are visible. Sunlight illuminates his face and the shoulder of his armor. Arthur Hughes’s painting, also titled “Sir Galahad” (1870), portrays a humanized Galahad who contrasts with his supernatural surroundings. While many artists depicted the unshakeable knight, Hughes’s painting shows a determined but humbled knight who leans over his horse while riding forward toward three brilliant angels at the upper right of the canvas. The angels are the source of light in the painting. Joseph Noël Paton’s “Sir Galahad and an Angel” (1884-1885) shows Galahad on horseback in front of a rock formation. An angel stands just slightly behind him; both figures gaze heavenward at the same angle. Other depictions of Galahad in art include Religion: The Vision of Sir Galahad and his Company (1852), a fresco designed by William Dyce for the Queen’s Robing Room in the Palace at Westminster, and a series of tapestries designed by Edward Burne-Jones that illustrate Malory’s “Tale of the Sankgreal” (Whitaker 199). The tapestries, designed for W. K. D’Arcy’s home at Stanmore Hall, include one called “The Attainment of the Holy Grail” (1898-9), which depicts Galahad gazing at the Grail; Perceval and Bors, though in the scene, are separated from Galahad and his vision by three angels.

In addition to his popularity in literature, Galahad has been a popular subject of visual representation. Galahad was often used to represent "inspired attacks on evil" (Whitaker 236). As in the poetry, many paintings of Galahad emphasize his perfection and purity; one famous example is "Sir Galahad" (1862) by George Frederic Watts (1817-1904). Watts’s Galahad is depicted in profile as he gazes forward and leads his horse; his helmet hangs behind him so that his curly hair and youthful, idealized facial features are visible. Sunlight illuminates his face and the shoulder of his armor. Arthur Hughes’s painting, also titled “Sir Galahad” (1870), portrays a humanized Galahad who contrasts with his supernatural surroundings. While many artists depicted the unshakeable knight, Hughes’s painting shows a determined but humbled knight who leans over his horse while riding forward toward three brilliant angels at the upper right of the canvas. The angels are the source of light in the painting. Joseph Noël Paton’s “Sir Galahad and an Angel” (1884-1885) shows Galahad on horseback in front of a rock formation. An angel stands just slightly behind him; both figures gaze heavenward at the same angle. Other depictions of Galahad in art include Religion: The Vision of Sir Galahad and his Company (1852), a fresco designed by William Dyce for the Queen’s Robing Room in the Palace at Westminster, and a series of tapestries designed by Edward Burne-Jones that illustrate Malory’s “Tale of the Sankgreal” (Whitaker 199). The tapestries, designed for W. K. D’Arcy’s home at Stanmore Hall, include one called “The Attainment of the Holy Grail” (1898-9), which depicts Galahad gazing at the Grail; Perceval and Bors, though in the scene, are separated from Galahad and his vision by three angels.

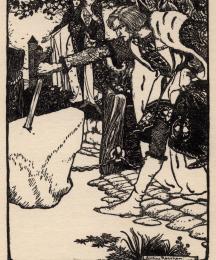

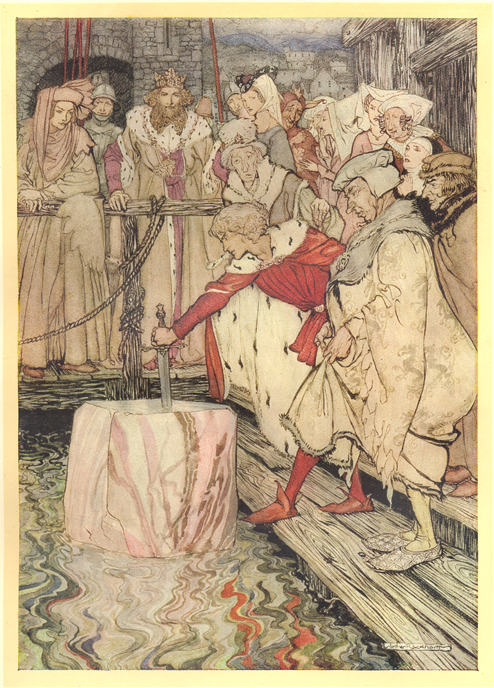

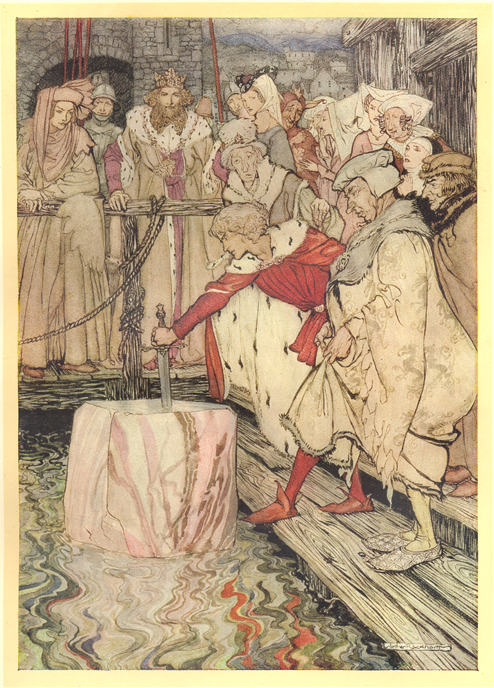

Illustrated books of the late Victorian period provide a particularly rich source of images of Galahad; for example, Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographic depictions were designed to accompany an illustrated edition of Tennyson’s Idylls (Mancoff, Return, 137). Arthur Rackham’s "How Galahad drew out the sword from the floating stone at Camelot" (left) first appeared in Alfred Pollard’s The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table (1917), an abridgement of Malory (Mancoff, Revival, 267). Rackham’s depictions emphasize the fantastic and grotesque elements to the scene he illustrates while maintaining established Arthurian imagery; in the process, his art creates an imaginative re-vision of the Arthurian tales (Mancoff, Revival, 268).

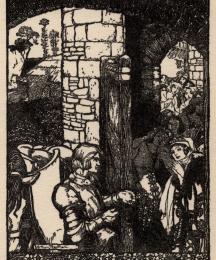

Later book illustrators include Howard Pyle, illustrator of The Story of the Grail and the Passing of Arthur (1910), and Anna-Marie Ferguson, whose art enriches the 2000 Cassell & Company edition of Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur (Lupack, Illustrating Camelot, 194, 219). Ferguson often depicts little-illustrated moments of Malory’s text, with a special emphasis on Arthurian women. For example, in addition to an illustration of Galahad on the Grail Quest, he also appears in an illustration of Perceval’s sister in which she offers her blood to save the lady of a castle (Lupack, Illustrating Camelot, 229).

Galahad's adventures are often anthologized for children, for whom the perfect knight is presented as a behavioral model and an inspiration. As a highly recognizable figure in Arthurian tradition, Galahad has been memorialized by video games, films (such as the 1950 Adventures of Sir Galahad directed by Spencer G. Bennet), rock bands, and toys. He also appears alongside Kay, Gawain, and Tristan in the Camelot 3000 comic book and in the 1991 DC comic Justice League Europe Annual.

BibliographyArmstrong, Dorsey. "The (Non-)Christian Knight in Malory: A Contradiction in Terms?" Arthuriana 16.2 (2006): 30-34.

Burns, James, M.A. “Sir Galahad: A Call to the Heroic.” London: James Clarke and Co., 1915.

Cherewatuk, Karen. "Born-Again Virgins and Holy Bastards: Bors and Elyne and Lancelot and Galahad." Arthuriana 11.2 (2001): 52-64.

Erskine, John. Galahad: Enough of his Life to Explain his Reputation. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1926.

Lacy, Norris J., ed. Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and post-Vulgate in translation. New York: Garland Publishing, 1993-1995.

Looper, Jennifer E. "Gender, Genealogy, and the ‘Story of the Three Spindles’ in the Queste del Saint Graal." Arthuriana 8.1 (1998): 49-66.

Lupack, Alan and Barbara Tepa Lupack. King Arthur in America. Rochester, NY: D. S. Brewer, 1999.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa, with Alan Lupack. Illustrating Camelot. Rochester, NY: D. S. Brewer, 2008.

Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte Darthur: The Winchester Manuscript. Ed. Helen Cooper. Oxford, New York: Oxford UP, 1998.

Mancoff, Debra A. The Arthurian Revival in Victorian Art. New York: Garland, 1990.

--. The Return of King Arthur: The Legend through Victorian Eyes. New York: Abrams, 1995.

Morgan, Mary Louis. Galahad in English Literature. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America, 1932.

Morris, William. “Sir Galahad: A Christmas Mystery.” ’The Defense of Guenevere’ and Other Poems. London: Bell and Daldy, 1858.

O’Malley, Jerome. "Sir Galahad: Malory’s Healthy Hero." Annuale Medievale 20: 33.

Phelps, Elizabeth Stuart. “The Terrible Test.” Sunday Afternoon 1 (Jan.): 49.

Poulson, Christine. The Quest for the Grail: Arthurian Legend in British Art, 1840-1920. Manchester, U.K.; New York: Manchester University Press, 1999.

Tennyson, Alfred, Lord. “The Holy Grail.” Idylls of the King. London: Edward Moxon, 1869.

--. “Sir Galahad.” Poems. London: Edward Moxon, 1842.

Waite, Arthur Edward. The Holy Grail: The Galahad Quest in Arthurian Literature. New York: University Books, 1961.

Watson, Jessica Lewis. Bastardy as a Gifted Status in Chaucer and Malory. Studies in Medieval Literature vol. 14. Lewiston, Queenston, Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press, 1996.

White, T. H. The Once and Future King. New York: Putnam, 1958.

Whitaker, Muriel. The Legends of King Arthur in Art. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1990.

Wright, Michelle R. "Designing the End of History in the Arming of Galahad." Arthuriana 5.4 (1995): 44-55.

Read Less