Elaine of Astolat/The Lady of Shalott

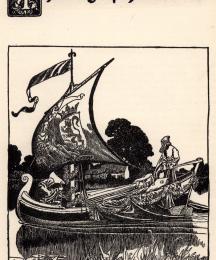

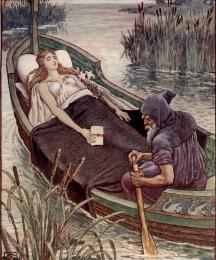

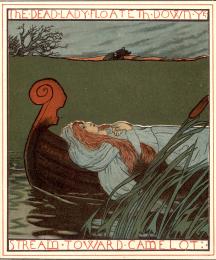

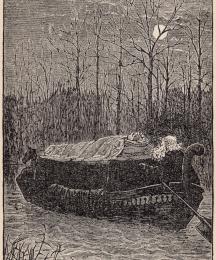

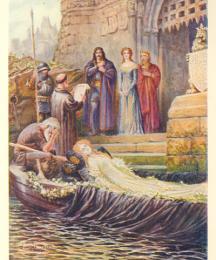

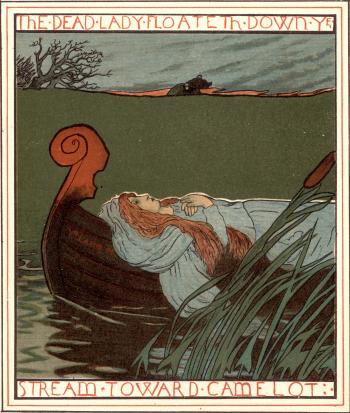

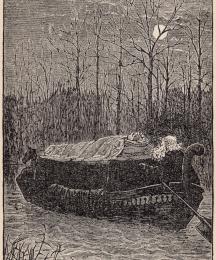

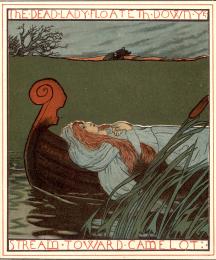

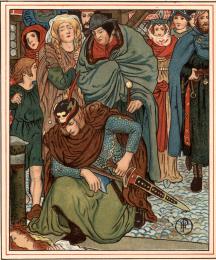

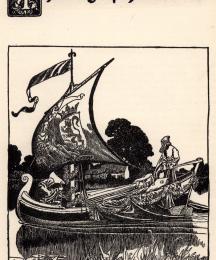

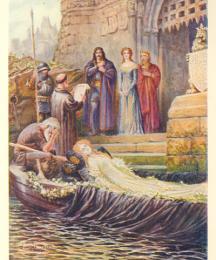

Elaine of Astolat, a character closely related to the Lady of Shalott, is an innocent maiden who falls deeply in love with Sir Lancelot. When he does not return her love, she dies of grief and floats in a barge down the river to Camelot. Elaine’s story is found in important works of literature by authors such as Malory and Tennyson, and she is also frequently represented in artwork. A favorite of illustrators, dead Elaine in her barge is a recurring theme among many artists, especially the pre-Raphaelites. In fact, Elaine seems to be an even more popular figure among the Victorians than she was in the Middle Ages. Her youth, pure love, and death aroused widespread admiration and pity in the Victorian audience. Though she is often critiqued by feminist critics as a passive figure, most versions of her narrative also give her some authorial control over her story, even as she remains a victim of hopeless love. Some contemporary versions of her story for younger readers attempt to rescue her from the role of victim and make her a more active figure.

- Elaine in Medieval Literature

- Elaine in Modern Literature

- Re-envisioning Elaine for Young Adult Literature

- Bibliography

ELAINE IN MEDIEVAL LITERATURE:

The story of the doomed maiden from Astolat appears in the “La Damigella di Scalot,” tale 82 of Il Novellino, a thirteenth-century collection of Italian tales. The Lady falls in love with Lancelot and dies when he does “not wish [voleva] to return her love” (109). The wording here indicates that Lancelot had some choice in selecting a lover and thus renders

Read More

Read Less

Elaine of Astolat, a character closely related to the Lady of Shalott, is an innocent maiden who falls deeply in love with Sir Lancelot. When he does not return her love, she dies of grief and floats in a barge down the river to Camelot. Elaine’s story is found in important works of literature by authors such as Malory and Tennyson, and she is also frequently represented in artwork. A favorite of illustrators, dead Elaine in her barge is a recurring theme among many artists, especially the pre-Raphaelites. In fact, Elaine seems to be an even more popular figure among the Victorians than she was in the Middle Ages. Her youth, pure love, and death aroused widespread admiration and pity in the Victorian audience. Though she is often critiqued by feminist critics as a passive figure, most versions of her narrative also give her some authorial control over her story, even as she remains a victim of hopeless love. Some contemporary versions of her story for younger readers attempt to rescue her from the role of victim and make her a more active figure.

- Elaine in Medieval Literature

- Elaine in Modern Literature

- Re-envisioning Elaine for Young Adult Literature

- Bibliography

ELAINE IN MEDIEVAL LITERATURE:

The story of the doomed maiden from Astolat appears in the “La Damigella di Scalot,” tale 82 of Il Novellino, a thirteenth-century collection of Italian tales. The Lady falls in love with Lancelot and dies when he does “not wish [voleva] to return her love” (109). The wording here indicates that Lancelot had some choice in selecting a lover and thus renders him more culpable than in later versions. Although the lady seems to have little control over her death, as “death came to her,” she does have considerable control over the manner in which her dead body will be presented to the court (109). Before dying, she orchestrates a lavish ship to carry her body to Camelot and commissions a letter explaining her death. The tale explains that “her instructions were executed exactly as she had said” (109). Despite the lady’s specific design, her journey requires some faith in that she plans for her corpse to be left without sail or oarsman in the sea and must assume that the waves will bring her to Camelot. Whereas other versions of the story imagine the maiden floating down a river, where she can count on the currents to bring her to her destination, Il Novellino’s depiction of the lady coming to Camelot by sea lends the death journey a sense of fate. The final words of the tale are those of the lady's letter, which calls Lancelot “the best knight in the entire world, and the cruelest one” (111).

The French Elaine story from the Mort Artu (in the Vulgate Cycle/Lancelot-Grail Cycle), also written in the thirteenth century, goes into much more detail than the Italian version does. Whereas Il Novellino gives us the bare facts of the tale and presents it in isolation from a larger story of the Round Table, the Mort Artu begins a tradition of extending the maiden’s sad tale and placing it in the context of a larger narrative. This version of the maiden is much more calculating than other Elaines tend to be. She tricks Lancelot into wearing her favor by first asking for an unspecified boon, and only reveals her wish once he promises to grant it to her. She tells him that he has agreed to wear her sleeve and “do battle for the love of me” (93). Lancelot is “displeased by the promise,” since the queen will surely be angry, but he must keep it anyhow “for it would be dishonorable for him not to do just what he had promised the young woman” (93). The Mort Artu thus presents the lady as actively manipulating Lancelot into granting her desires and shows Lancelot struggling with an impossible situation on account of the maiden’s clever ploy.

After hearing that Lancelot has been wounded, the maiden again takes action by finding him and helping heal his wounds. The image of the maiden as Lancelot’s healer becomes an important feature of her character in later versions, and it plays a vital role in that it puts Lancelot in her debt. This text explains that the maiden “stayed with him night and day, loved him so much, both because others spoke so highly of him and because she found him so handsome, that she thought she could not go on living if she did not have his love” (101). When the maiden seeks Lancelot’s love, she again uses leading questions in order to do so, asking not directly about his feelings but instead inquiring whether he thinks it would be “ignoble for a knight to refuse if [she] asked for his love” (101). This time, however, Lancelot is more cautious in his response; he replies that a knight would be ignoble if his heart were free to give, but that a man could not be blamed if he “didn't have sovereignty over himself” (101). Despite the care with which Lancelot answers her questioning, the maiden responds that “you'll soon cause my death. If you had told me this a little less directly, you would have let my heart languish in fond hope, and such hope might have let me live in all the joy and delight a love-stricken heart can know” (102).

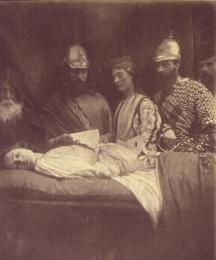

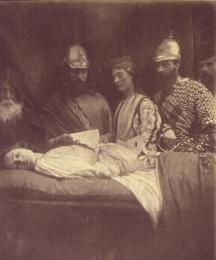

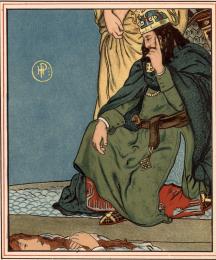

Her denunciation of Lancelot’s actions continues in the letter she has placed with her corpse, so that the whole Round Table will blame him as well. In this version, we do not see her preparations for death. Instead, King Arthur and Sir Gawain see a boat float up with her body in it and find her letter, which explains that she “suffered the pain of death … for the most valiant and yet the vilest man in the world: Lancelot of the Lake” (114). The king responds with sympathy for the maiden and anger at Lancelot, claiming that “‘the wicked thing he did to you is so terrible and so despicable that he should be condemned by all’” and suggesting that they “‘inscribe her tomb to explain how she died, so that those who come after us will remember her’” (114). Not only does the king provide for her funeral, but he has the maiden “buried in the main church of Camelot” with the inscription “HERE LIES THE MAIDEN OF ESCALOT, WHO DIED FOR LOVE OF LANCELOT” (114). The inscription gives the maiden’s perspective on events both preeminence and permanence and links Lancelot’s name with hers for all to see.

The Stanzaic Morte Darthur (fourteenth century), with its source in the Mort Artu, also gives us a maiden who is far more aware of the ramifications of her actions than later versions of the notoriously passive figure. The maiden is not given a proper name in this version, and is simply called The Maid of Ascolot throughout. The first we hear of her is that “Th'erl had a doughter that was him dere;/ Mikel Launcelot she beheld” [The earl had a daughter who was dear to him;/ She beheld Launcelot intently]1 (lines 177-8). The text, therefore, provides no context for the maiden, no sense of what she was like before she met and loved Launcelot. Another particular feature of this version is that Launcelot is immediately clear with the maiden about his inability to love her. There is never any room for misunderstanding. He tells her, “‘In another stede mine herte is set;/ It is not at mine owne will’” [‘My heart is set in another place;/ It is not under my command’] (lines 203-204). She responds by requesting that “‘Sithe I of thee ne may have more,/ As thou art hardy knight and free,/ In the tournament that thou wolde bere/ Some sign of mine that men might see’” [‘Since I may have no more of you,/ As you are a bold and noble knight,/ In the tournament if you would bear/ Some sign of mine that men might see’] (lines 209-212). In other words, she asks for him to wear her favor as a kind of consolation prize, and she does so with full knowledge of his emotional unavailability.

In other versions of the story, the maiden takes on the role of healer when Launcelot is wounded in the tournament, but in this version the earl’s son tends Launcelot with his aunt. Texts that position the maiden as Launcelot’s healer put him in a position of indebtedness to her for her help. This version, then, gives us no reason to see Launcelot as misleading or owing the maiden in any way. Yet when Gawain arrives, the maiden tells him that Launcelot has taken her for his lover. If she had said that he was her beloved, her words could be construed as accurate, since she does love him, but instead she claims that he has taken her “[f]or his leman” [for his love], and there is no ambiguity in her statement (line 582). It is difficult to understand her motivations, and perhaps she was simply believing what she wanted to believe about Launcelot’s wearing of her favor, but it is not Gawain who misrepresents the situation in this version, but the maiden herself.

We do not get the maiden’s viewpoint after Gawain leaves her, so, as with the Mort Artu, we are not witnesses to her decline. Instead, Arthur and Gawain are talking and see her boat float up with her body in it. Again very much in keeping with the Mort Artu, Arthur and Gawain alone spot the boat and search inside to find the maiden and her letter. Although the text does not include her perspective before she dies, it does feature her words in epistolary form. As in the Mort Artu, her letter is particularly harsh toward Launcelot, addressing her complaint to “King Arthur and all his knightes” and accusing Launcelot of terrible behavior, calling him “churlish” twice and “unhende” (discourteous) once (lines 1048; 1078; 1083; 1081). Arthur’s response is immediately sympathetic: he says that Launcelot “was gretly to blame” and should hereafter have “wicked fame” since the maiden “died for grete loving” (lines 1099; 1101; 1102).

Thus the king himself reprimands Launcelot without hearing his side of the story; he claims that the knight will have shame forever as a result of the maiden’s death. The letter that the maiden writes, though we do not see her write it, nonetheless functions as the definitive version of her story in this text. Because the text is missing a section (which presumably includes the maiden’s burial), we do not know how her tomb is inscribed, but it is likely that it is similar to the Mort Artu in providing her with a burial that gives her story preeminence. Her words are approved and validated by the king’s response, and dying “for grete loving” seems to be not only a reasonable cause of death but a wholly sympathetic one, a fact which continues throughout the tradition.

Thomas Malory’s Morte D’Arthur, the most famous medieval version of the fair maid’s story, expands her role and gives her a name. No longer just “the maiden,” Elaine is a fully-developed character. Malory expands Elaine’s function in his version of the tale, and in fact makes her not just a plot device but a vivid character in her own right. Malory’s version of the figure is more sympathetic and much less aggressive in personality than in the Mort Artu and Stanzaic Morte. Unlike those ladies, Malory’s maiden never blames Launcelot. The fact that both Elaine and Launcelot are more sympathetic in this text aligns with Malory’s consistent interest in portraying Launcelot positively.

The first time we meet “the Fayre Maydyn off Astolat,” we hear that “ever she behylde sir Launcelot wondirfully” [she always beheld Launcelot with wonder] (623). Malory tells us that “she keste such a love unto sir Launcelot that she cowde never withdraw hir loove, wherefore she dyed” [she cast such a love onto sir Launcelot that she could never withdraw her love, on account of which she died] (623). Even though she is passive in that she dies for her unrequited love, Elaine is also outspoken and assertive in many of her actions. Initially, she asks Launcelot directly to wear her favor and later asks him directly to be her husband, or at least her lover. Perhaps even more surprising, she takes over Gawain’s quest when she searches for the missing knight. Even as she performs the more traditionally feminine role of healer, she is only able to do so because she has taken on a quest assigned by King Arthur himself. In many ways, her role as healer comes to define her. Her care keeps Launcelot alive, and his departure leads to her own death. Launcelot tries to give her options other than death, but she will have none of it. He offers to provide her with a dowry to marry another, but she responds matter-of-factly: “‘Alas! Than’, seyde she, ‘I must dye for youre love’” [‘Alas! Then,’ she said, ‘I must die for your love’] (638). Her assertion here challenges the world of romance, since she is not imperiled in a way that can allow for masculine rescue. Neither Launcelot nor her brothers nor her father nor anyone else can save her once she asserts her coming demise.

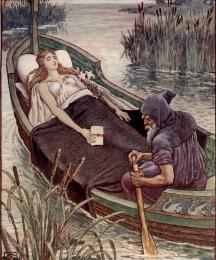

It is in fact the detail that goes into Elaine’s death, and her orchestration of that death, that differs most dramatically from the earlier versions. In those versions, her death occurs offstage, but here we are with her as she prepares to die. Knowing that she’ll die, she first requests to dictate a letter, and then pronounces the way in which her father and brother should arrange her body. She requests that “‘whyle my body is hote lat thys letter be put in my ryght honde, and my honde bounde faste to the letter untyll that I be colde’” [‘while my body is warm let this letter be put into my right hand, and my hand bound tightly to the letter until I am cold’] (640). The letter thus provides the link between living maiden and dead maiden. There are a number of ways that she ensures the delivery of her letter and maintains control over it. First of all, she asks that a mute oarsman row her barge, a situation which assures that someone will be present to make sure the barge goes where she wants while also assuring that no one will be present who can provide an alternate version of her story. She does not leave the narrative to a messenger who could choose his own words, but makes sure that her exact words are those that reach her audience. The letter she dictates will indeed be the final word given to the court.

As she floats to Camelot, Elaine is the subject of gossip and speculation, but her entrance into the city, though it occurs after her death, manages to quiet all rumors and replace them with her own perspective. Unlike what occurs in earlier versions, the letter gains a wider audience among the court. Launcelot is not present for the reading, but everyone else is. As a deathbed epistle, Elaine’s version of the tale holds authority, and Malory expands upon this authority by giving us the letter in its entirety:

Moste noble knyght, my lorde sir Launcelot, now hath dethe made us two at debate for youre love. And I was youre lover, that men called the Fayre Maydyn of Astolate. Therefore unto all ladyes I make my mone, yet for my soule ye pray and bury me at the leste, and offir ye my masse-peny: thys ys my laste requeste. And a clene maydyn I dyed, I take God to wytnesse. And pray for my soule, sir Launcelot, as thou arte pereless. (641)

[Most noble knight, my lord sir Launcelot, now death has made the two of us in opposition because of your love. And I was your lover, that men called the Fair Maiden of Astolat. Therefore unto all ladies I make my complaint, yet pray for my soul and bury me at least, and offer my mass-penny: this is my last request. And a pure maiden I died, I take God to witness. And pray for my soul, sir Launcelot, as you are without peer.]

As critics have noted, this version of her letter differs from others, such as that of the Stanzaic Mort Arthur, which place great blame on Launcelot. In Malory’s telling, she holds Launcelot up as a peerless knight to the last and focuses not on vengeance, but rather on asserting her own character and making her post-mortem requests. She wants a proper burial, she wants a mass-penny, and she wants everyone to know that she loved Launcelot and died a pure maiden. Thus Elaine can not only assure that her story is properly understood, but she can tell that story in such a way that it will have real efficacy for her, even after her death. By the time they call in Launcelot, “the kynge, the quene and all the knyghtes wepte for pité of the dolefull complayntes” [the king, the queen and all the knights wept for pity because of the sorrowful complaints] (641). Launcelot does get his say here, but public feeling is on the maiden’s side before he even enters the scene, and she ultimately receives all that she requests in the letter.

ELAINE IN MODERN LITERATURE:

The brief and tragic story of Elaine gathered momentum during the Victorian era. It was Tennyson’s poem “The Lady of Shalott” and his Elaine section in the Idylls of the King that really gained fame. An explosion of images of Elaine occurred in varying mediums after Tennyson wrote his versions of her story.

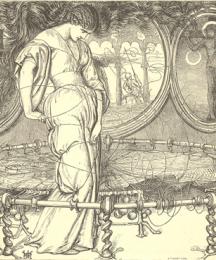

Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” (1842) is one of the most striking popular narratives of the lady. Tennyson claimed to have not yet read Malory when he wrote “Lady of Shalott,” but to have been influenced instead by “La Damigella di Scalot.” Yet Tennyson’s poem creates a narrative different from any that came before. Rather than meeting and falling in love with Lancelot, this lady is set apart from the world and only spies Lancelot through a window. The opening of the poem presents the lady as isolated and stationary in her tower, while the people and geography outside all progress toward Camelot. The road runs “[t]o many-tower’d Camelot,” the river is constantly “[f]lowing down to Camelot,” and the people who pass by are moving toward Camelot as well (line 5; 14). She stays alone in her tower, where she weaves a tapestry and only sees “[s]hadows of the world” as reflected in a mirror (line 48). Her whole life is taken up by weaving a “magic web with colours gay” out of these reflections, and she knows that a mysterious curse will descend upon her if she ever looks toward Camelot (line 38). As the poem continues, it becomes clear that the lady’s separation from the world is limiting to her. As knights pass, the narrator comments that the lady “hath no loyal knight and true,” and then, when newly-wed lovers pass by, we get the lady’s own words for the first time: she states bluntly, “‘I am half sick of shadows’” (line 62; 71). When Lancelot rides by and his reflection appears in the mirror, the lady moves her gaze for the first time away from the mirror and to the window:

She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces thro’ the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look’d down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me!’ cried

The Lady of Shalott. (109-117)

This most famous scene shows the lady in motion for the first time; a moment of unmediated sight is quickly followed by the tangled web and cracked mirror of the curse. The lady’s response is to find a boat, write her name across the prow so that people will know it is she, and float toward Camelot, singing as she dies. There is no mute oarsman to steer the way, but it seems instead inevitable that the lady will reach Camelot, since she has entered the world and the world moves inexorably in that direction. The poem ends famously with Lancelot gazing upon the lady and commenting that “‘[s]he has a lovely face;/ God in His mercy lend her grace,/ The Lady of Shalott.’” (lines 169-171). An earlier version of the poem, written in 1833, ends instead with onlookers finding “a parchment on her breast” that reads:

The web was woven curiously

The charm is broken utterly,

Draw near and fear not – this is I,

The Lady of Shalott.

Although this parchment differs greatly from the letters of earlier narratives, it nonetheless ends the poem with her own words. The 1842 version shifts the focus from the lady’s perspective to Lancelot’s. He looks upon her, not knowing that she has died as a result of looking upon him.

The poem has been hugely influential in both British Literature and popular culture, and it spawned countless artistic renderings. Famous Pre-Raphaelite images by artists such as John William Waterhouse, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti depict two main episodes: the moment the curse comes upon the lady and her journey down the river to Camelot. Continued fascination with these artistic renderings has kept the story alive. More recently, Loreena McKennitt adapted the poem to music for her 1991 album The Visit, and the music video for The Band Perry’s 2010 song If I Die Young features the lead singer reading and holding the poem while floating down a river.

“The Lady of Shalott” has also inspired a flurry of critical attention. It is widely regarded as a poem about the artist figure, since the Lady must focus on her weaving and is cursed for looking at the world outside. Another main critical reading of the poem is that it represents anxieties surrounding Victorian gender norms that imagine a binary between public/private or active/domestic. As with other Elaines, when the Lady of Shalott enters the world she dies into a beautiful corpse, an object for the gaze of the court. Yet her role as artist figure also continues in Tennyson’s other great Elaine poem, “Lancelot and Elaine.”

“Lancelot and Elaine” (1859), from the Idylls of the King, follows Malory's version of the Elaine story much more closely. The poem opens with a description of her as:

Elaine the fair, Elaine the loveable,

Elaine, the lily maid of Astolat,

High in her chamber up a tower to the east

Guarded the sacred shield of Lancelot. (1-4)

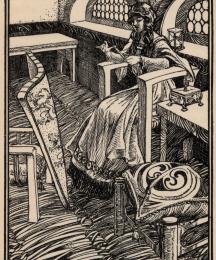

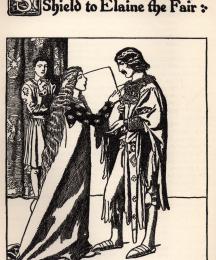

The opening of the poem, which dives right in to a description of Elaine, places the focus completely on her. Like the Lady of Shalott, this lady is isolated in a tower, and like that lady, this one is an artist figure, sewing and decorating a shield cover for Lancelot. Unlike the Lady of Shalott, however, Elaine has already met and fallen in love with him, and the art she creates is for him specifically. The context, then, for her time in the tower is quite distinct from the Lady of Shalott’s, and yet the opening image evokes that earlier poem. Even the Lady of Shalott’s curse might be connected to Elaine’s tragic fate. When Lancelot arrives, “she lifted up her eyes/ And loved him, with that love which was her doom” (lines 242; 258-59).

This version of the lady is more modest than earlier iterations, in keeping with Victorian norms. Elaine is barely able to look up to Lancelot’s face, and yet once she does it is “as if it were a God’s” (line 354). When she asks him to wear her favor, it is with a sense of unaccustomed recklessness. Yet she is also clever, convincing him to take her favor by pointing out that it will help him in his anonymity. When he tells her that he has never done so much for a maiden before, she is filled with delight, and when he gives her his shield to keep safe, “Then to her tower she climbed, and took the shield,/ There kept it, and so lived in fantasy” (lines 395-96). When Gawain arrives on his quest for Lancelot, she rebuffs his advances, and when he asks if she loves Lancelot, her reply demonstrates both her devotion and her innocence: “‘I know not if I know what true love is,/ But if I know, then, if I love not him,/ I know there is none other I can love’” (lines 672-74). Elaine says nothing to Gawain about whether Lancelot loves her, yet he passes the gossip around the court quite purposefully. Unlike her previous iteration in the Stanzaic Morte, Elaine here in no way misleads Gawain, willfully or otherwise.

As in Malory, everyone is talking about Elaine before her boat floats in, but unlike Malory the talk is more pointed. The people of Camelot “Had marvel what the maid might be, but most/ Predoomed her as unworthy,” and the queen hates her with a jealous passion (lines 723-24). Yet Elaine herself is unaware of such reactions, and Tennyson describes her as an innocent child, sitting on her father’s lap and begging to be allowed to seek her knight. She asks to go so that she will not be “found as faithless in the quest,” and claims that she dreams that Lancelot is gaunt and pale “for lack of gentle maiden’s aid,” and needs for her “to be sweet and serviceable” to him (lines 756; 760; 762). Again, she speaks in terms of innocence and feminine virtue. She focuses not on the quest itself, but on her ultimate objective of fulfilling the appropriately feminine role of caretaker and nurturer. Lancelot thinks of her as a child, and toward him she is “Meeker than any child to a rough nurse,/ Milder than any mother to a sick child,/ And never woman yet, since man’s first fall,/ Did kindlier unto man” (lines 852-55).

Even Elaine’s proposal to Lancelot, which might seem shockingly forward, is written as modestly as possible. When she pleads to be his wife, she does it while “innocently extending her white arms,” and instead of asking to be his mistress, as she does in Malory, she simply wants “to be with you still, to see your face,/ To serve you, and to follow you through the world” (lines 933-34). Perhaps we can infer an extramarital romantic relationship in her request, but it is not explicit. It seems that she would be willing to continue to serve and take care of him as she has been doing while he recovered from his wound. And where Malory’s Elaine was willful in her death, Tennyson’s Elaine thinks upon her death “as a little helpless innocent bird,” reinforcing yet again her blamelessness (line 889).

Though this Elaine is a sweet and submissive Victorian ideal, she nonetheless maintains some authorial control. She channels the creativity she used in sewing the shield case into writing and singing a song called “The Song of Love and Death.” And then, when she is giving instructions for the letter and the deathbed barge, she explains that when her body reaches Camelot, “There surely I shall speak for mine own self,/ And none of you can speak for me so well” (lines 1118-19). She never blames Lancelot in any way and is devoted to him throughout, but she still wants to tell her story in her own way and in her own time. When Elaine’s boat arrives, it is Lancelot who sees her first in this version. He is looking out on the water in despair when he sees her float up, “smiling, like a star in blackest night” (line 1235). Even in her death, she shines as a beacon of hope and goodness in the tainted world that Camelot has become.

The poem contains Elaine’s entire letter, which is similar to the one in Malory, but interesting in that it has an added sense of action. The letter is addressed to Lancelot, and he is there when it is discovered (as opposed to what happens in earlier versions). In this version, Lancelot parts from Elaine without bidding her farewell (at her father’s request), and her letter indicates that “I, sometime called the maid of Astolat,/ Come, for you left me taking no farewell,/ Hither, to take my last farewell of you” (lines 1265-67). Here she imagines her voyage as a final movement toward Lancelot after he has moved away from her. Even though she is dead at this point, her image of herself is active. Lancelot mourns her death, “for good she was and true,” though he reminds everyone that “to be loved makes not to love again” (lines 1283; 1286). Therefore, Tennyson’s version allows both Elaine and Lancelot to be piteable. And everyone, including the queen, does pity Elaine. She is buried “like a queen” (line 1325), and then Arthur announces:

‘Let her tomb

Be costly, and her image thereupon,

And let the shield of Lancelot at her feet

Be carven, and her lily in her hand.

And let the story of her dolorous voyage

For all true hearts be blazoned on her tomb

In letters gold and azure!’ (1328-34)

Thus her image and her story become jointly immortalized on her tomb, and the court responds to her post-mortem arrival precisely as she plans. And readers responded in kind. One contemporary critic in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine sums up the general approval of Elaine as a model of feminine virtue when he writes that “we would advise that numerous class of readers, who have not the time, or, which comes to the same thing, fancy they have not, to read long poems, to skip the first two Idylls boldly, and at once make acquaintance with ‘Elaine the fair, Elaine the lovable,’ as her admiring bard very meetly styles her” (615).

As with “The Lady of Shalott,” “Lancelot and Elaine” captured the imagination of the Pre-Raphaelite artists of the nineteenth century, and images of Elaine from both Tennyson and Malory (usually of her floating down the river, though sometimes also sewing Lancelot’s sheld cover) have been popular ever since. With Tennyson’s sympathetic portrayal of the lovely, doomed girl, the obscure medieval character found her way into the public eye.

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps responds to Tennyson with her short story, “The Lady of Shalott” (1871). Known for promoting social issues and complicating the romanticism of the Arthurian legends, Phelps places the Lady of Shalott in a nineteenth-century slum amid squalor and disease. The story opens as if we are learning little-known facts about a well-known story: “It is not generally known that the Lady of Shalott lived last summer in an attic, at the east end of South Street.” Phelps continues in this vein, explaining that the Lady’s mother “threw her down-stairs one day, by mistake, instead of the whiskey-jug” when she was only five years old. The following one-sentence paragraph notes drily that “[t]his is a fact which I think Mr. Tennyson has omitted to mention in his poem.”

The tone of the story is satirical, and yet the ultimate effect is deeply moving. The crushing poverty of the nineteenth-century slums is expressed through the person of a seventeen-year old girl stuck in an attic where she lacks the health or strength to even rise from bed. Her only solace is a small mirror through which she can see the world outside—a world of hungry and sick children, dead bodies carried away, and a dirty hydrant. We are told specifically that this hydrant, which replaces the flowing river of Tennyson's poem, is the only source of water for the entire building. Like Tennyson’s Lady, the girl in this story is trapped away from the world, only glimpsing it through a glass rather than through a window or in person. The narrator explains, “I suppose that one must go through a process of education to understand what comfort there may be in a ten by six inch looking-glass. All the world came for the Lady of Shalott into her little looking-glass,—the joy of it, the anguish of it, the hope and fear of it, the health and hurt,—ten by six inches of it exactly.”

The story increases in tragedy with each paragraph, and The Lady of Shalott’s curse comes in the form of young boys, who are throwing stones and happen to hit (and smash) the mirror. This Lady never looks out the window, never even gets out of bed. The outside bursts into her attic world and breaks the mirror through no action of her own. When a doctor, who happens to be visiting the neighborhood, rushes up to see if anyone is hurt, he finds the girl, unhit by the stone and yet nonetheless shattered. She explains, “‘I’d rather it was me than the glass. Oh, my glass! My glass! But never mind. I suppose there'll be some other—pleasant thing.’” The doctor, “looking sorrowfully about the room,” wonders “[w]hat other ‘pleasant thing’ could even the Lady of Shalott discover in that room last summer, at the east end of South Street?” When she explains that she has been in bed her whole life, but has always had the mirror, the doctor makes the connection to Tennyson’s poem and cries, “‘Ah! … the Lady of Shalott!’”

The doctor makes it clear that the girl could be cured if she had proper attention, and he promises to send the Board of Health to South Street. The Board of Health finally comes to check on things, but they find “a pine board, and the Lady of Shalott lay on it, in her brown calico night-dress, with Sary Jane's old shawl across her feet. The Flower Charity (Heaven bless it!) had half-covered the old shawl with silver bells, and solemn green shadows, like the shadows of church towers.” This Lady of Shalott dies because help does not come in time, she dies of poverty and neglect, and she dies without ever even looking out of the window.

Howard Pyle’s The Story of Sir Launcelot and his Companions (1907) also makes a selfless martyr of Elaine, but he depicts her as a spiritual medieval woman rather than as a poor contemporary girl. He takes the lovable Elaine from Tennyson and renders her even more saintly. Pyle’s text conflates Elaine of Astolat with Elaine of Corbenic in order to make her the mother of Galahad. He also makes her Launcelot’s wife, so that his duty is to her rather than to Queen Guinevere. Launcelot first hears about Elaine via a story about the Worm of Corbin, a monster plaguing Elaine’s land. Unlike the miracle that Launcelot usually performs in freeing Elaine of Corbenic from individual torment (see T. H. White, below), Launcelot here simply demonstrates his prowess and bravery by defeating the Worm. Yet his quest does lead him to Elaine. When Launcelot first sees her, he thinks that she is “the most beautiful maiden that ever he had beheld in all of his life” (121). Unlike most versions of Elaine of Astolat, in which we follow Elaine’s gaze on Launcelot, here we have an extended depiction of Launcelot’s gaze on Elaine.

The first we hear of Elaine’s viewpoint is on the way to the tournament at Astolat (a location that explicitly identifies her with Elaine of Astolat), when she encourages Launcelot to participate in the fighting. Unlike other versions of Elaine, this maiden convinces him to fight and is present at the tournament. Her attendance renders her a more active participant, or at least a more aware one, rather than a naïve girl imagining things she has never seen. When she learns that it is Launcelot upon whom she has bestowed her favor, she is joyful that such a great knight would honor her, but also “she forecast that nothing but sorrow could come to her who had placed her heart and all her happiness in the keeping of this knight, who had no heart or happiness to bestow upon any lady in return” (154). This Elaine implicitly knows that Launcelot cannot return her love—she is, again, not a naïve girl, but rather aware of whom she loves and what he can and cannot provide her.

As in Malory and Tennyson, Elaine asks her father if she may go on a quest to seek Launcelot after he is injured, but in this version the quest is her own idea, not one she inherits from Gawain. When she finds Launcelot, he tells her, “‘Lady, God knows I am no happy man. For even though I may see happiness within my reach yet I cannot reach out my hand to take it. For my faith lieth pledged in the keeping of one with whom I have placed it and that one can never be aught to me but what she now is” (161-62). Elaine responds with sorrow for both of them: “‘Alas, Launcelot, I have great pity both for thee and for me’” (162). Her care for him in his infirmity and the sympathy they share links Launcelot to the maiden, and when the Queen sends messengers to ask him to return to King Arthur’s court, he both desires to go and feels he must stay. It is Elaine herself who tells Launcelot that he should go because she sees how much he longs to be back at Arthur’s court. Once he leaves, “she wept in great measure, for it was as though she had cut off her hope of happiness with her own hand, as though it had been a part of her body” (165).

When the Queen’s anger at Launcelot drives him insane, Elaine must tend to him once again. In his illness, “death was very close to Sir Launcelot and there was but one thought in his mind and that thought was to return to Corbin. For even through his clouds of madness, Sir Launcelot wist that there at Corbin a great love awaited him and that if he might reach that place he might there have rest and peace” (191). And Elaine saves him by recognizing him and making sure that he is cared for. When he wakes, miraculously cured of his madness, he gazes at her and says, weeping, “‘Elaine, meseems I have no hope of honor save in thee’” (196).

The most exceptional feature of Pyle’s version is that Launcelot and Elaine marry. It seems Pyle required them to marry in order to allow for Galahad’s birth without a scandal. Lancelot tries very hard to be a good husband, and when he learns that the Queen wishes him to return to court, he refuses because “‘a duty that is greater than any queen’s command keeps me here with this lady unto whom I have pledged all my truth and all my faith’” (288). Once again it is Elaine who convinces him to return to court, but he agrees only if she will accompany him. When Elaine arrives at court, people think that “even Queen Guinevere herself is not more beautiful than yonder lady” (301). Guinevere responds to her rival with false friendliness, offering her a chamber next to her own royal one (with the true purpose of keeping Launcelot and Elaine apart).

It is at this point that we can see traces of the lovesick girl from earlier versions of Elaine’s story. Separated from Launcelot, Elaine grows sick and weak, neither eating nor sleeping. As in Elaine of Corbin’s story, Elaine’s maid sneaks Launcelot into Elaine’s room. When the Queen calls Launcelot a traitor for this meeting, he asks, “‘In what way have I betrayed myself, and in what way am I a traitor to thee or to anyone? Is not my duty first of all toward that lady to whom I have sworn my duty?’” (304). Despite his pointed questions, Guinevere orders Elaine to leave court, and Elaine leaves “with great dignity” (306). The Queen then commands Launcelot to remain at court, and his continued allegiance to the Queen emerges when he tells no one, not even Elaine, that he stays by the Queen’s order rather than his own choice. Nonetheless, Elaine remains strangely calm, and says that “‘it mattereth but very little indeed that such things as this befall a poor wayfarer in this brief valley of tears’” (307). While she is serene, she also grows increasingly ill, and Launcelot does not know that she has taken to her sickbed.

Elaine remains in her sickbed until she gives birth to Galahad, while Launcelot continues at court with no knowledge of her illness or the baby’s birth. Her words before her death present themselves in sharp contrast to the willful girl dying from romantic love in early versions of the narrative. She repeats the prophecy that her son Galahad will achieve the Holy Grail and explains,

‘My time draweth near, for even now I behold the shining gates of Paradise, though it yet is that I behold them faintly, as through a vapor of mist. Yet anon that mist shall pass, and I shall behold those gates very near by and shining in glory; for soon I shall quit this troubled world for that bright and beautiful country. Nevertheless, I shall leave behind me this child who lieth beside me, and his life shall enlighten that world from which I am withdrawing.’ (331)

In Pyle, her pronouncements are all spiritual in nature, and her arrangements are for her son. She says nothing about displaying her body or floating to Camelot. In fact, her brother Lavaine organizes everything after her death, and the manner in which her body is displayed and delivered is his own idea. And instead of a missive from Elaine herself, Lavaine accompanies the corpse on its way and accuses Launcelot harshly: “‘Hah! art thou there, thou traitor knight? Behold the work that thou hast done; for this that thou beholdest is thy handiwork. Thou has betrayed this lady’s love for the love of another, and so thou hast brought her to her death!’” (338). Launcelot responds with deep remorse and leaves the court without a word to anyone. Once he leaves, mass is sung for Elaine’s “pure and gentle soul” and her body “was buried in the minster and a monument of marble was erected to the memory of that kind and loving spirit that had gone” (340). This ending allows Elaine to be saintly and sweet, while still placing blame on Launcelot through her brother. Though in many ways this is the most positive depiction of Elaine, it also removes her authorial power from the ending, as she passively accepts her fate and does not attempt to narrate her story after her death, leaving her hopes for the world with her son.

Like Pyle’s version, T. H. White’s Once and Future King (1958) blends Elaine of Astolat and Elaine of Corbenic. The character we initially meet resembles Elaine of Corbenic. We are told that she is in a place called Corbin, and, like that Elaine, Lancelot must save her from a magical spell that keeps her constantly in a pot of boiling water. Only “the best knight in the world” can get her out of the boiling water, and Lancelot is able to prove he is the best knight in the world by saving her (400). Even as the scene clearly echoes Elaine of Corbenic, however, White also associates this maiden with Elaine of Astolat by describing her innocent and undying love for Lancelot. Lancelot is “too simple to see that if the finest knight in the world rescued you out of a kettle of boiling water, with no clothes on, you would be likely to fall in love with him” (403). The love of an innocent maiden for Lancelot, which characterizes the Astolat story, is here heightened by the addition of the miraculous rescue of that maiden. As with Elaine of Corbenic, Lancelot is tricked into sleeping with this maiden in order to conceive Galahad. But the circumstances surrounding the trick here are less about the fated birth of that perfect knight and more about Elaine’s unreciprocated love. Whereas Pyle’s maiden gives birth to Galahad in honorable wedlock with no real mention of the conception, this maiden tricks Lancelot into an illicit union. The butler and nurse help the lovesick girl by getting Lancelot drunk (and perhaps using a love potion on him), and then convincing him that Elaine is Queen Guenever. Lancelot is horrified in the morning, believing his status as best knight is ruined forever by his loss of virtue. He feels that “[t]he thing which Elaine had stolen from him was his might. She had stolen his strength of ten” (406). The entire episode with Elaine proves to be transformative for Lancelot. It gives him his first miracle and demonstrates his clear preeminence, but it also leads to the loss of his virginity, which he believes will hinder him from performing any further miracles. It leads to his affair with the queen, since he goes to her when he leaves Elaine, but it also leads to the jealousy and misery between himself and the queen, since she can never fully believe that he does not desire Elaine.

After Elaine gives birth to Galahad, she comes to Camelot to try to win Lancelot from Guenever. Her emotion and motives at this point resemble Elaine of Astolat’s, but she comes to court while still alive and knowingly goes up against the queen. Again she tricks Lancelot into sleeping with her while believing he was with the queen. In fact, neither the reader nor Lancelot knows that it was Elaine he spent the night with until the queen erupts in anger. Elaine speaks up honestly, admitting that she fooled Lancelot and saying simply that she “‘could not live without him’” (427). Nonetheless, the encounter (and the queen’s wrathful jealousy) triggers Lancelot’s madness, as it does in Malory’s version of the Elaine of Corbenic story. Elaine openly blames the queen for driving Lancelot mad.

The novel continually contrasts Elaine with the queen in terms of beauty and personality. Whereas Pyle’s Elaine shines in splendor, this Elaine, though humble and sweet, is bland and charmless compared with Guenever. After Lancelot’s madness and disappearance, we learn that “Elaine had done the ungraceful thing as usual. Guenever, in similar circumstances, would have been sure to grow pale and interesting—but Elaine had only grown plump” (439). Elaine understands Lancelot better than the queen does, but she is simply not the vibrant character that the queen is. Yet she does indeed show more concern for Lancelot’s feelings. While Lancelot lies in bed recovering after his episode with madness, Elaine could nurse him constantly, but “something in her heart—either decency, or pride, or generosity, or humility, or the determination not to be a cannibal” leads her to visit him only once a day (442). In many stories her nursing is what makes Lancelot indebted to her, but here it is her restraint from nursing him. As he recovers, he agrees to live with her, though not to marry her. In this version he can make a life with her outside of marriage because they already have a son, which contrasts with all of the above versions. When he leaves her again, Elaine does not try to stop him, only asking to know whether he will return to her one day. He promises to come back, a fact that gives her a reason to live. When he rides up to her castle twenty years after leaving it, Lancelot finds “that Elaine [is] waiting for him on the battlements, in the same attitude as that in which he had left her twenty years before” (529). When she asks him to wear her favor in a tournament, she does not do so boldly, as she does in some other version, but rather “humbly and childishly” and only because she believes that he has returned to be with her (532). When he is wounded, this time she does nurse him herself, yet he must tell her that he plans to leave her again, and she dies soon after. In White’s version, unlike any other, Elaine’s death is clearly described as suicide. The narrator explains that Elaine “now struck the only strong blow of her life. She struck it unintentionally, by committing suicide” (534).

When Elaine finally floats to Camelot, it is as a middle-aged woman rather than a young maiden. She is pitiful, but not a beautiful corpse. The narrator describes a “death-barge” carrying “the plump partridge who had always been helpless. Probably people commit suicide through weakness, not through strength” (534). The assumption of suicide here is jarring, since traditional Elaine narratives never broach the subject. It is a huge departure from the usual depictions of Elaine to describe her as anything but a beautiful victim of love. The text explains that “[e]verybody went down to see the barge. It was not a lily maid of Astolat they saw, but a middle-aged woman whose hands, in stiff-looking gloves, grasped a pair of beads obediently. Death had made her look older and different. The stern, grey face in the barge was evidently not Elaine—who had gone elsewhere, or vanished” (535). The image, then, is in stark contrast to the usual lovely maiden covered in flowers made so famous in pre-Raphaelite artwork. Even the reference to the “lily maid” directly contrasts this image with Tennyson’s. She is pitiable, and in keeping with other versions even the queen pities her (more surprising in this version, since the queen has actually met Elaine and has had two decades to build up her jealousy), but she is not beautiful.

RE-ENVISIONING ELAINE FOR YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE

Traditional versions of Elaine’s story present us with a doomed figure dying for love, but some texts for girls attempt to recuperate the legend as a model for young women by allowing her to survive.

L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables (1908) pokes fun at the popularity of both the Tennyson poems and the artistic renderings of lovely Elaine in her barge when Anne decides to act out Elaine’s watery journey and ends up feeling wet and uncomfortable rather than romantic. Anne studies Tennyson’s poem in school, and wishes she had lived in Camelot. “Those days, she said, were so much more romantic than the present” (320). She and her friends decide to act out the story, and she plays Elaine in a chapter called “An Unfortunate Lily Maid.” As Anne floats along, her romantic notions are challenged when the boat begins to leak and she must act quickly to save herself from drowning. Her final assessment of the situation is pretty clear: “‘I don’t ever want to hear the word ‘romantic’ again’” (328). Although it concerns a modern girl playing Elaine (rather than Elaine herself), this variation on the story calls attention to the problems with romanticizing a young woman’s death and offers us a heroine who rejects passivity in favor of survival. The music video for The Band Perry’s If I Die Young (see "Modern Literature," above) follows a similar trajectory, as singer Kimberly Perry climbs out of her boat once it begins to fill with water, avoiding watery death and returning to her loved ones.

Meg Cabot’s novel Avalon High (2005) follows Montgomery in making Elaine a contemporary girl and a heroic figure rather than victim of hopeless love. The novel, though it takes place in a modern high school, explicitly responds to the source material. It features a high school girl named after Elaine of Astolat, and each chapter opens with a stanza from “The Lady of Shalott.” Ellie is disenchanted with her lovesick namesake, noting that “[t]he only thing my namesake and I had remotely in common was a mutual love of floating . . . although I preferred to do mine on a raft in a pool, whereas Elaine of Astolat favored floating to her death in a boat . . .” (133). Her rejection of the Elaine role comes to fruition when she turns out to instead represent the Lady of the Lake and to be a strong and heroic figure. When one character insults her, for example, she responds that she knows he means “[t]hat there’s nothing Elaine of Astolat could do here. But that was fine, because I wasn’t Elaine of Astolat, no matter what he might think. And there was plenty Elaine Harrison could do here” (262). Like the character in Sandell’s book, Ellie is able to save the day by overcoming her hopeless love and focusing instead on larger goals. A film of Avalon High came out in 2010, increasing the character’s heroic position even further by making her a King Arthur figure rather than the Lady of the Lake.

Lisa Ann Sandell’s lyrical novel Song of the Sparrow (2007) also gives us an Elaine who is initially lovesick for Lancelot, but ultimately saves everyone with her heroic actions. Unlike the young adult novels discussed above, Song of the Sparrow seems at first more traditional in that it places Elaine in the medieval court of King Arthur rather than in the modern world. She is a healer figure and an integral part of King Arthur’s community. Though she cannot fight with the men on the battlefield, Elaine feels that she provides valuable healing services and should be included in Round Table discussions. She reasons at one point, “I fight these wars/ with my healing./ Why should they keep me/ from the Round Table?” (34). She finally proves her worth when she is shot on her way to warn the knights of an attack. She appears dead as she floats up in her barge, but is actually only wounded and is able to save the day. Quite unique in Elaine stories, this heroine is asked to join the Round Table and is able to find a happy ending as part of the community she loves. The author's note at the end makes her purpose clear: “As I imagined Elaine, who truly has suffered at the hands of male writers, I wanted to give her strength and power and relevance. And indeed, it is without a sword that she manages to save her friends and loved ones” (394).

Barbara Tepa Lupack’s The Girl's King Arthur: Tales of the Women of Camelot (2010) features a tale called “Elaine of Astolat,” which tells the story from Elaine’s perspective. Unlike the above versions, this version gives us the traditional story of a maiden falling in love with Lancelot and pining to death. Although Lupack follows the basic plotline of Malory, she shifts the emphasis of the story by giving us Elaine’s point of view. The tale opens with the line, “The moment I saw him, I knew that I loved him. And I knew I would never love anyone else again,” indicating to readers right away that we are entering the story through Elaine’s own mind and feelings (49). She is also an adventurous person. When her brother Lavaine is to go as Lancelot’s squire, she remarks, “How I envied him! I wished that it could have been me, not Lavaine, embarking on such a grand adventure” (51). She has her own adventure when she is called to Arthur's court after Lancelot goes missing, and when Gawain explains that her knight is injured, she rides off to find him “with such haste that it must have seemed as if all the devils from hell were at my back” (55). She says of herself, “No knight ever rode with more determination. No warrior ever displayed a more abiding sense of purpose. I was bold and fearless – because I had to be. Nothing was going to deter me from finding Lancelot so that I could nurse his injuries and restore him to good health” (55). When she proposes marriage and Lancelot denies her, she states clearly, “‘If you cannot pledge yourself to me, so be it. That's your choice. I too have a choice to make. And I choose not to live without your affection.’” (60). She chooses to die, and the text shows her death as a deliberate act even as it switches to the third person: “Having made her peace, Elaine closed her eyes and willed herself to die” (62). As usual, she dies only after planning her post-mortem journey and penning her letter to Lancelot, which we get in full:

Most noble Lord, now death has parted us. Ascribe no blame to yourself, for I blame you not. I, whom men call the Lily Maid of Astolat, set my love upon you, and I have died for your sake. When I gave you my love, I did so fully and faithfully. My love was such that I expected nothing in return. Yet I received untold pleasure just in the giving.

This, then, is my last and only request of you: pray for my soul and offer the Mass-penny for me. Then bury my body in Camelot, so that I may always be near you and sleep for eternity in your view. Grant me this, my love, for you are a peerless knight.

And remember this: I do for you what no other damsel has ever done. (62-63)

People respond to the letter with pity, as in earlier versions, but they also feel that the maiden’s death has taught them something. Lancelot and Guinevere both learn a lesson about true love and the brevity of life. Of Lancelot, the narrator explains that “for many years afterward, he found in her fierce love a lesson to be emulated” (63). Guinevere thinks that Elaine's love was “foolish” because “no love is worth the complete sacrifice of self,” but she also found “something about her love that I cannot help but admire, even envy. Elaine knew her mind, and she would not be deterred by father or brother or priest” (63; 64). In other words, this version of Elaine’s story includes a lesson in strength for readers even as it remains true to the sad ending of the original narrative. The final message seems to be Guenevere’s perspective on Elaine: “Elaine's life and death had taught the Queen a liberating lesson that she carried with her until her own death at Amesbury—that however fantastic or unconventional a woman's ambition might seem to others, she must always be true to her own heart and mind” (64).

For more on Elaine/The Lady of Shalott, see Reclaiming the Death of a Beautiful Woman: Female Voices Adapting the Lady of Shalott.

Footnotes1. All Translations of Middle English provided by Kristi J. Castleberry.

PRIMARY SOURCES:

Avalon High. Dir. Stuart Gillard. Disney-ABC Domestic Television, 2010. Film.

The Band Perry. “If I Die Young.” Dir. David McClister. YouTube. 28 May 2010. Web. 28 May 2014. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7NJqUN9TClM&feature=kp>

Cabot, Meg. Avalon High. New York: Harper Collins, 2006.

“La Damigella di Scalot.” Novellino, or, One hundred ancient tales: an edition and translation based on the 1525 Gualteruzzi editio princeps. Ed. and Trans. by Joseph P. Consoli. New York: Garland Pub., 1997. Pp. 109-110.

The Death of Arthur. Trans. and Ed. Norris J. Lacy. In Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation, Volume IV. New York: Garland Publishing, 1995. Pp. 91-160.

Hunt, William Holman. The Lady of Shalott, c. 1890-1905. Oil on canvas. Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT.

“The Idylls of the King.” Rev. of The Idylls of the King, by Alfred Lord Tennyson. In Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine 86.529 (November 1859): Pp. 608-627.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa. The Girl's King Arthur: Tales of the Women of Camelot. Illustrated by Ian Brown. Dallas, Texas: Scriptorium Press, 2010.

Malory, Thomas Works. Ed. Eugène Vinaver. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Phelps, Elizabeth Stuart. “The Lady of Shalott.” On The Camelot Project. University of Rochester. Web. 28 May 2014. < http://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/text/phelps-lady-of-shalott>

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Lady of Shalott. In Poems [The Moxon Tennyson]. London: Edward Moxon, 1857. P. 75.

Sandell, Lisa Ann. Song of the Sparrow. New York: Scholastic Press, 2007.

Stanzaic Morte Arthur. In King Arthur's death: The Middle English Stanzaic Morte Arthur and Alliterative Morte Arthure. Ed. Larry D. Benson. Rev. Edward E. Foster. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 1994. Pp. 11-128.

Tennyson, Alfred Lord. “The Lady of Shalott (1833 & 1842 Versions).” On The Camelot Project. University of Rochester. Web. 28 May 2014. <http://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/text/tennyson-shalott-comparison>

---. “Lancelot and Elaine.” On The Camelot Project. University of Rochester. Web. 28 May 2014. < http://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/text/tennyson-lancelot-and-elaine>

Pyle, Howard. The Story of Sir Launcelot and his Companions. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1985.

Waterhouse, John William. The Lady of Shalott 1888. Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

White, T.H. The Once and Future King. London: HarperCollins, 1996.

SECONDARY SOURCES:

Armstrong, Dorsey. “Gender, Marriage, and Knighthood: Single Ladies in Malory.” In The Single Woman in Medieval and Early Modern England: Her Life and Representation. Ed. Laurel Amtower and Dorothea Kehler. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Reneaissance Studies, 2003. Pp. 41-61.

Aurbach, Nina. “The Rise of the Fallen Woman.” In Nineteenth-Century Fiction 35.1 (June 1980): Pp. 29-52.

Davidson, Roberta. “Reading Like a Woman in Malory’s Morte Darthur.” In Arthuriana 16.1 (Spring 2006): Pp. 21-33.

Donavin, Georgiana. “Elaine's Epistolarity: The Fair Maid of Astolat's Letter in Malory's Morte Darthur.” In Arthuriana 13.3 (2003): Pp. 68-82.

---. “Locating a Public Forum for the Personal Letter in Malory's Morte Darthur.” In Disputatio: An International Transdisciplinary Journal of the Late Middle Ages, Volume 1: The Late Medieval Epistle. Ed. Carol Poster and Richard Itz. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1996. Pp. 19-36.

Field, P.J.C. “Time and Elaine of Astolat.” In Studies in Malory. Ed. James W. Spisak. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 1985. Pp. 231-236.

Fries, Maureen. “Female Heroes, Heroines, and Counter-Heroes: Images of Women in Arthurian Tradition.” In Arthurian Women: A Casebook. Ed. Thelma S. Fenster. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996. Pp. 59-74.

Gray, Erik. “Getting It Wrong in ‘The Lady of Shalott.’” In Victorian Poetry 47.1 (Spring 2009): Pp. 45-59.

Hares-Stryker, Carolyn. “The Elaine of Astolat and Lancelot Dialogues: A Confusion of Intent.” In Texas Studies in Literature and Language 39.3 (Fall 1997): Pp. 205-29.

---. “Lily Maids and Watery Rests: Elaine of Astolat.” In Victorian Literature and Culture, Vol. 22. Ed. John Maynard and Adrienne Munich. New York: AMS Press, 1995. Pp. 129-51.

Hassett, Constance W. and James Richardson. “Looking at Elaine: Keats, Tennyson, and the Directions of the Poetic Gaze.” In Arthurian Women: A Casebook. Ed. Thelma S. Fenster. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996. Pp. 287-304.

Holbrook, Sue Ellen. “Emotional Expression in Malory's Elaine of Ascolat.” In Parergorn 24.1 (2007): Pp. 155-78.

Howey, Ann F. “Reading Elaine: Marjorie Richardson’s and L. M. Montgomery’s Red-Haired Lily Maids.” In Children’s Literature Association Quarterly (2007): Pp. 86-109.

Joseph, Gerhard. “Victorian Weaving: The Alienation of Work into Text in ‘The Lady of Shalott.’” In Tennyson. Ed. Rebecca Stott. London; New York: Longman, 1996. Pp. 24-32.

Knepper, Janet. “A Bad Girl will Love You to Death: Excessive Love in the Stanzaic Morte Arthur and Malory.” In On Arthurian Women: Essays in Memory of Maureen Fried. Ed. Bonnie Wheeler and Fiona Tolhurst. Dallas: Scriptorian Press, 2001. Pp. 229-43.

Lukitsh. Joanne. “Julia Margaret Cameron’s Photographic Illustrations to Alfred Tennyson’s The Idylls of the King.” In Arthurian Women: A Casebook. Ed. Thelma S. Fenster. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996. Pp. 247-62.

Lupack, Alan. “Malory's Intratexts.” In Romance and Rhetoric: Essays in Honour of Dhira B. Mahoney. Ed. Georgina Donavin and Anita Obermeier. Turnhout: Brepols. 2010. Pp. 249-68

---. The Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa, with Alan Lupack. Illustrating Camelot. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2008.

Martin, Molly. Vision and Gender in Malory’s Morte Darthur. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2010.

Noble, James. “Gilding the Lily (Maid): Elaine of Astolat.” In On Arthurian Women: Essays in Memory of Maureen Fried. Ed. by Bonnie Wheeler and Fiona Tolhurst. Dallas: Scriptorian Press, 2001. Pp. 45-57.

Parry, Joseph D. “Following Malory out of Arthur's World.” In Modern Philology 95.2 (November 1997): Pp. 147-69.

Poulson, Christine. The Quest of the Grail: Arthurian Legend in British Art 1840-1920. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1999.

---. “‘The True and the False’: Tennyson’s Idylls of the King and the Visual Arts.” In The Arthurian Revival: Essays on Form, Tradition, and Transformation. Ed. Debra N. Mancoff. New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1992. Pp. 97-114.

Psomiades, Kathy Alexis. “‘The Lady of Shalott’ and the critical fortunes of Victorian Poetry.” In The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Poetry. Ed. Joseph Bristow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Pp. 25-45

Reynolds, Rebecca L. “Elaine of Astolat's Death and the Ars Moriendi.” In Arthuriana 16.2 (2006): Pp. 35-9.

Shichtman, Martin B. “Elaine and Guinevere: Gender and Historical Consciousness in the Middle Ages.” In New Images of Medieval Women: Essays Toward a Cultural Anthropology. Medieval Studies: Volume 1. Ed. Edelgard E. DuBruck. Lewiston, Queenston, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1989. Pp. 254-71.

Simpson, Arthur L., Jr. “Elaine the Unfair, Elaine the Unlovable: The Socially Destructive Artist/Woman in ‘Idylls of the King.’” In Modern Philology 89.3 (February 1992): Pp. 341-62.

Tennyson transformed : Alfred Lord Tennyson and visual culture. Ed. Jim Cheshire. Farnham, Surrey: Lund Humphries, 2009.

Udall, Sharyn R. “Between Dream and Shadow: William Holman Hunt’s ‘Lady of Shalott.’” In Women’s Art Journal 11.1 (Spring – Summer 1990): Pp. 34-38.

Walsh, John Michael. “Malory's Characterization of Elaine of Astolat.” In Philological Quarterly 59.2 (Spring 1980): Pp. 140-49.

Wright, Jane. “A Reflection on Fiction and Art in ‘The Lady of Shalott.’” In Victorian Poetry 41.2 (2003): pp. 287-90.

Read Less

The Lady of Shalott (1833 & 1842 Versions) - 1859-1885 (Author)

The Lady of Shalott (1833 Version) - 1833 (Author)

The Lady of Shalott (1842 Version) - 1842 (Author)

Lancelot and Elaine - 1859-1885 (Author)

Images Gallery