Dinadan comes to prominence in the 13th century in the French Prose Tristan, where he is a foil to those knights who unquestioningly accept the assumptions of chivalry and courtly love. In the 14th-century Italian Tavola Ritonda, Dindano is the cousin of Breus sanz Pietà. He comments on the folly of love but becomes devoted to Tristano. When Marco (Mark) is captured after killing Tristano, Dindano tries to kill him, an act for which he himself would have been put to death—since Artù (Arthur) will not allow the slaying of a prisoner—had Marco himself not pardoned him for the offense.

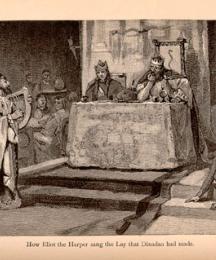

In Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, Dinadan remains a mocker of chivalry but, as in earlier sources, he is brave when called upon to fight. He admires good knights like Tristram and Lamorak and says self-deprecatingly that although he is not “of worship” himself, he loves those who are. Hated only by “murtherers,” according to Malory, Dinadan has great affection for Lamorak, which wins him the enmity of Gawain and Agravaine, who ultimately slay him. Contemptuous of Mark, Dinadan writes a scathing lay about him, which he teaches to the harper Eliot so he can perform it before Mark. (Ernest Rhys constructs the mocking lay supposed to have been made by Dinadan in his poem “The Lay of King Mark” [1905].)

In Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, Dinadan remains a mocker of chivalry but, as in earlier sources, he is brave when called upon to fight. He admires good knights like Tristram and Lamorak and says self-deprecatingly that although he is not “of worship” himself, he loves those who are. Hated only by “murtherers,” according to Malory, Dinadan has great affection for Lamorak, which wins him the enmity of Gawain and Agravaine, who ultimately slay him. Contemptuous of Mark, Dinadan writes a scathing lay about him, which he teaches to the harper Eliot so he can perform it before Mark. (Ernest Rhys constructs the mocking lay supposed to have been made by Dinadan in his poem “The Lay of King Mark” [1905].)

Guiterman, Arthur (1871 - January 11, 1943)

Rhys, Ernest (1859 - 1946)

Aubrey Beardsley (1872 - 1898)

F. A. Fraser (1846 - 1924)

Alfred Kappes (1850 - 1894)

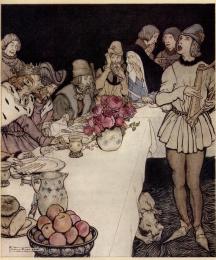

Arthur Rackham (1867 - 1939)

Aubrey Beardsley (1872 - 1898)

F. A. Fraser (1846 - 1924)

Alfred Kappes (1850 - 1894)

Arthur Rackham (1867 - 1939)