Medieval Dagonets

The earliest depiction of Dagonet appears in the early 13th century in the Prose Lancelot. Dagonet stumbles upon Lancelot when the latter was in such a state of distraction that he nearly drowned himself. Taking advantage of the situation, Dagonet grabs hold of Lancelot’s horse and declares the knight his prisoner. When Dagonet returns to court with the “captured” Lancelot, the other knights are highly amused, since Dagonet “was of course a knight, but he was a witless fool and the most cowardly excuse for a man that anyone knew of, and people made fun of him for his wild boasts” (Lacy 111). The depiction of Dagonet in the prose Lancelot does not even approach the level of his later life as the beloved fool of Arthur. ...

Read More

Read Less

Dagonet, most simply, is King Arthur’s court fool. Also called Daguenet, and often carrying an epithetical surname such as “the Fool” or “the Coward,” the character is perhaps most interesting in that he did not begin his fictional existence as a fool at all. Enid Welsford’s 1935 book, The Fool: His Social and Literary History, still the authority on the topic, discusses medieval fools in great detail from both an historical and a literary context, citing a staggering number of examples. Dagonet is never mentioned by Welsford. Through most of his early appearances, Dagonet was depicted as a knight who was foolish. The character's modern interpretation, extending over a long literary afterlife, depicts Dagonet as a court fool who was knighted. This iteration of the character was first established by the Prose Tristan and later expanded by Malory.

Medieval Dagonets

The earliest depiction of Dagonet appears in the early 13th century in the Prose Lancelot. Dagonet stumbles upon Lancelot when the latter was in such a state of distraction that he nearly drowned himself. Taking advantage of the situation, Dagonet grabs hold of Lancelot’s horse and declares the knight his prisoner. When Dagonet returns to court with the “captured” Lancelot, the other knights are highly amused, since Dagonet “was of course a knight, but he was a witless fool and the most cowardly excuse for a man that anyone knew of, and people made fun of him for his wild boasts” (Lacy 111). The depiction of Dagonet in the prose Lancelot does not even approach the level of his later life as the beloved fool of Arthur. Rather, he brags about his “capture” of Lancelot, and seems to annoy people more than entertain them. There is a note of derision in the voices of the queen, Yvain, and the others at court when they speak to or about Dagonet. When Guenevere learns that Lancelot was the knight “captured” by Dagonet, she reacts in shock, exclaiming, “What?...Was it you who were taken prisoner by Daguenet the Coward?” (Lacy 144). Though Dagonet is first referred to as “Daguenet le fou,” the sense in which it is used is one of derision, not of title, and “fool” is only one of many derisive labels applied to the braggart knight in his brief appearances in the prose Lancelot.

Dagonet’s next medieval appearance came in the Guiron le Courtois, part of the French romance, Palamedes, which dates roughly between 1234 and 1240. In this tale, a character named Hervi narrates a short series of episodes relating to Dagonet, here depicted as a madman more than an incompetent. Hervi encounters Dagonet half naked and fighting another knight. The narrator learns that Dagonet had once been one of the best knights at King Arthur’s court, another significant change from the Lancelot portrayal, but that he went mad after the abduction of his wife. Hervi pursues Dagonet, who continues to fight with knights who try to help him. At one point, Dagonet stabs a knight only because the man had attempted to dissuade Dagonet from swimming across a river. Eventually, Dagonet terrorizes a courtyard of people who end up pursuing him while throwing stones. Afterwards, Hervi learns Dagonet’s full story. Before going mad, Dagonet won a tournament for the hand of his lord’s daughter. Though Dagonet marries her, his friend Helior also falls in love with her, and abducts her while Dagonet is distracted in battle. During a grueling, two month search for his wife, Dagonet devolves into madness, and roams the countryside looking for her. The only way to calm him down is to say, “look, King Arthur’s coming!”

Dagonet next appeared in the late 13th Century text, Les Prophecies De Merlin. The Prophecies center around the False Guinivere story, which connects two plots—The Tournament and The Saxon Invasion. Arthur, due to the false Guinivere, is so apathetic that he disregards a messenger from Vincestre bringing news of the Saxon’s intent to attack Britain. Dagonet, in a surprisingly competent move, sends the messenger on to Galeholt, who takes charge of Arthur’s forces and ultimately brings about a victory over the Saxons.

In one episode, Sagremor le desree criticizes Arthur for “the decline of his court” which he has entrusted to “Daguenet le fou.” Like many of the modern versions of Dagonet, he is shown here to be loyal to Arthur, and refuses to listen to Sagremor’s criticism of the king. Ironically, Dagonet is seemingly quite capable at the job, and he has “money laid aside wherewith to pay the forces [in the impending battle against the Saxons at Vincestre], and…he has ordered them to be prepared with arms and horses for the war” (Paton 389). Dagonet further pays for the mercenaries traveling with Gawain and Mordret and arranges for Gawain to receive the royal gonfalon, thus convincing the assembled forces to march to Vincestre.

In a later episode (Paton 396-97), Dagonet has apparently depleted the entirety of the treasury due to giving “money so freely to Sagremor to pay the mercenaries” (396). The episode depicts a conflict between Dagonet and Fole, the king’s treasurer. As in Guiron le Courtois, Dagonet’s loyalty to the king is highlighted. Dagonet is not stirred to action by Fole’s criticisms of his fiscal management but rather when Fole accuses him of potential treachery. It is only when Fole “ironically” asks Dagonet why he hasn’t “laid hands on Arthur’s crown,” that Dagonet engages him in a fight, ultimately killing Fole. Dagonet’s positive reputation is also once more highlighted, as the “people of the castle protect him from the indignant kindred of Fole.” While Dagonet and Sagremor are searching for the royal crown (which, per Sagremor’s notion, they plan to give to Fole’s family to placate them), they stumble upon a secret chamber where Arthur had stored “all the treasure that formerly belonged to Bertolais.” They use that treasure to pay off Fole’s family, pay the remaining soldiers who had not been paid before, and pay the soldiers of Yvain, who marches on to Vincestre after Arthur assures him that “he is satisfied with all that Daguenet has done” (397).

Ultimately, Les Prophecies De Merlin, offers a more nuanced portrayal of Dagonet than Lancelot or Guiron. Dagonet’s reputation for incompetence from Lancelot is still intact and he is still referred to as Dagonet the fool—again without enough context to distinguish between the title and the epithet—but this text offers a more positive portrayal of the character, possibly due to the larger role that he has compared to the two earlier texts. In the Prophecies, Dagonet begins the tale by sending a messenger to a more receptive audience, and then reappears throughout the episodes as a caretaker of the kingdom, handling fiscal matters and twice sending reinforcements to Vincestre to repel the Saxons. Dagonet even manages to kill a man in battle—even though the man is merely an uppity accountant—and Dagonet’s role as Arthur’s stand-in seems to be crucial to the victory over the Saxons.

Dagonet appeared again in the mid 13th century Prose Tristan. This text is significant for several reasons. Not only was it the first to tie the Tristan and Iseult plot to the Arthurian narrative, but it would later be a major source for Malory. Dagonet appears twice in the Prose Tristan, both depicting him in a combat situation, and neither showing him in a positive light. In an edition titled The Romance of Tristan, translated by Renee L. Curtis, Dagonet is shown getting soused in a well by Tristan. Dagonet, called “Sir Daguenet the Fool” in this scene, stops to drink at a well with a pair of squires. Tristan souses Dagonet in the well, causing a group of shepherds to laugh at the fool and his squires. Later, Dagonet’s group returns, seeking revenge upon the shepherds. Tristan intervenes, taking up Dagonet’s sword and using it to cut the arms off of one of the squires who had attacked the shepherds.

Dagonet briefly appears in a second story in the Prose Tristan, once again losing a battle, in the story The Vallet a la Cote Mautailliee. A young knight called Cote Maltailliee (poorly-fitting coat) is attempting to escort a lady on her journey. The lady seems reluctant, doubting the young knight’s honor and ability. They shortly encounter Dagonet, who is introduced as King Arthur’s fool, and he challenges Cote Maltailliee to a joust. Dagonet is portrayed as a madman who hates Cornish knights, seeking them out to joust. While Dagonet is quickly defeated, the Lady still taunts Cote Maltailliee for having bothered to fight a knight lacking in honor like Dagonet.

In the Prose Tristan, Dagonet’s status is far more ambiguous than in the earlier texts. Before, Dagonet was clearly a knight who was foolish and cowardly. Here, there is at least the possibility that he was Arthur’s official fool. In The Vallet a la Cote Mautailliee, Dagonet is described as a foolish man who was made a knight in order to entertain the court. While this does seem to indicate similarities between Dagonet and a court fool, it should be noted that a traditional fool would already have a place at court, regardless of his status as a knight, or lack thereof. The Prose Tristan shows that Dagonet’s knighthood was not conferred out of affection for a pre-existing court fool—as Malory and subsequent authors indicate—but rather to give him the right to be at the court in the first place. Regardless, the Prose Tristan took the initial steps that would transform Dagonet the foolish knight into the now familiar Dagonet the knighted Fool.

For nearly two hundred years after the Prose Tristan, Dagonet seems to have vanished. While it is unknown whether Dagonet was a neglected character or simply a character whose tales are no longer extant, Arthur’s fool made his grand return in Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. Malory offered greatly expanded adaptations of both of the Dagonet appearances from the Prose Tristan, while also inserting some new material. Initially, Dagonet has a small role in the La Cote Male Tayle, Malory’s version of the young knight forging his reputation. La Cote, so named by Sir Kay for arriving in Camelot in an ill-fitting coat, is a young knight who, perhaps foolishly, takes up the dangerous quest of a mysterious woman. Shortly after La Cote leaves on this quest, Kay “ordains” Dagonet, “kynge Arthurs foole,” to follow after him and “profyr hym to juste.” Dagonet does just that, as he “cryed and bade make hym redy to juste” before La Cote “smote sir Dagonet ovir his horse croupyr” (Vinaver 462). La Cote’s mysterious companion mocks him for his “victory,” and claims that he was shamed in Arthur’s court because they sent a fool to be his opponent on his first joust.

Malory later depicts his version of Dagonet’s encounter with Sir Tristram at the well. Tristram had been living in the wilderness with herdsmen and shepherds, half naked and clipped, by his companions, with shears so that he looked like a fool. On a hot day, Dagonet and two of his squires pass through and stop for a drink at a well. Seemingly for no reason, Tristram “sowsed sir Dagonet in that welle” and then did the same to his squires before making all three “lepe up” on their horses and “ryde their ways” (Vinaver 496). Later, Dagonet and his squires, upset that the shepherds had laughed at them, decide to go and return the favor. Tristram arrives and defends the shepherds, who had provided him with food, if not a good haircut. Tristram “gate sir Dagonet by the hede, and there he gaff hym such a falle to the erthe and brusede hym so that he lay stylle” (Vinaver 498). Using Dagonet’s sword, Tristram cuts off the head of one of the squires, which caused the other to flee. Dagonet goes to King Mark, warning him not to go near the well due to a mad fool who “had allmoste slayne me.” Mark assumes that the mad fool was Sir Matto le Breune, a good knight who lost his wits when he lost his lady to Gaheris. This draws together both the running theme of misrecognition with Mark that will be featured in the next episode, and shades of Dagonet’s earlier origins as a good knight gone mad over lost love.

Dagonet’s final, and best known, appearance in Malory depicts his role in a practical joke played at King Mark’s expense. Dynadan, initially siding with Mark, plans to challenge six knights of the Round Table to a joust. When Mark flees from this challenge, Dynadan realizes that the Camelot knights were “better frendis than I went they had ben” and he forsakes Mark, often referred to as the Cornish Knight. As a means of payback, Dynadan tells Mark that Lancelot is in the group of Camelot knights, and he describes the shield that would identify Lancelot. Dynadan, knowing that Lancelot was not actually there, describes Mordred’s shield instead. Mordred then decides to “put my harneys and my shylde uppon sir Dagonet and let hym sette uppon the Cornyshe knight,” a plan that is met with enthusiasm and great mirth by all, including Dagonet (Vinaver 588). When Dagonet, dressed as Mordred and mistaken for Lancelot, makes his challenge, Mark promptly flees for his life, with Dagonet giving chase.

This episode does a great deal to establish Dagonet’s role in Malory’s Camelot. When Dagonet first arrives, Sir Gryfflet announces “…here have I brought sir Dagonet, kynge Arthurs foole, that is the beste felow and the meryeste in the worlde” (Vinaver 587). Where some earlier Dagonets were at best tolerated and at worst despised by the court, here, Dagonet is portrayed as a beloved figure. When Dagonet chases after Mark, Sir Uwayne and Sir Brandules, though laughing wildly, quickly mount their own horses to follow them and make sure no harm came to Dagonet. They note that “kynge Arthure loved hym passynge well and made hym knight hys owne hondys” (Vinaver 588). They further state that Dagonet opens every tournament by making Arthur laugh, and they knew they needed to ensure his safety.

They do not quite succeed in doing so. When a fleeing Mark comes across a knight at a well—nobody realizing that the knight is a disguised Palomides—the knight “bare a speare to sir Dagonet and smote hym so sore that he bare hym over his horse tayle, that nyghe he had brokyn his necke” (Vinaver 589). Palomides then proceeds to smite all of the Camelot knights in short order. Later, back at court, the knights are gleefully retelling the story of Dagonet as Mordred/Lancelot chasing Mark through the countryside. Curiously, the response to the tale was “grete lawghynge and japynge at kynge Marke and at sir Dagonet” (Vinaver 603). It is curious that Dagonet was held up for ridicule when all seven Camelot knights were roundly defeated by Palomides. Regardless, Malory’s additions to the Tristan source material move the character in the direction of the formal court fool. The earliest medieval portrayals of Dagonet depicted him as a hapless knight who was a source of aggravation to the rest of the court. The Prose Tristan added the distinction that Dagonet was in fact knighted as a means to allow him access to the court so they could laugh and scorn at his foolishness. Malory’s interpretation of the character was one in which the court fool, due to his loyalty and talent, was knighted and much beloved by the entire court.

Modern Dagonets

Dagonet began his post-medieval literary afterlife in the 16th century. Shallow, an inept justice in Shakespeare’s 2 Henry IV, informs Falstaff that the men he has selected for conscription are lacking in the talents that make for a good soldier. The scene plays on notions of wrongness and mistaken identity. Shallow critiques the conscripts, saying “He is not his craft’s master; he doth not do it / right. I remember at Mile-end Green, when I lay at / Clement’s Inn—I was then Sir Dagonet in Arthur’s / show,--there was a little quiver fellow, and a’ / would manage you his piece thus’” (3.2.278-282). The irony, and humor, of the line is that Shallow lectures Falstaff based on his authority of having played the Arthurian fool. Falstaff knows the role all the better, as he is the Shakespearean fool.

Unfortunately, Dagonet was again largely forgotten for a period of about three hundred years. Where Malory restored the character after his first disappearance, Alfred Lord Tennyson and Edgar Fawcett revived him once again in the late 1800s. This time, however, the revival seemed to grab firmer footing, and Dagonet experienced a veritable explosion of interest from the latter part of the 19th century through the first quarter of the 20th century. Though Dagonet’s role in Tennyson’s epic Idylls of the King is not large, it does establish some of the tropes that would define his modern characterization. Dagonet appears only once, in one of the later idylls, “The Last Tournament,” first published in the December 1871 issue of Contemporary Review.

The tale, depicting the beginning of the end of Camelot, features a rhetorical battle of sorts between Dagonet, “whom Gawain in his mood / Had made mock-knight of Arthur’s Table Round,” and Tristram. Tristram, who had just disgraced a tournament by airing Lancelot’s affair in front of the court, is irked to find Dagonet dancing without music. When Tristram, who refers to Dagonet as “Sir Fool,” plays music for him to dance to, Dagonet immediately stops dancing, only to start up again the moment Tristram stops playing. In response to Tristram’s questions, Dagonet demonstrates both the loyalty and the perception that will define the character in the fifty years to follow. He verbally jousts with Tristram, letting him know that he would rather be a fool and “Skip to the broken music of my brains / Than any broken music thou canst make” ; thus he criticizes Tristram for both his uncourteous behavior at the tournament, and his immoral dalliances with the married Isolt.

Tennyson establishes Dagonet as a character fiercely and almost uniquely loyal to Arthur. Dagonet makes reference to a star he calls “the harp of Arthur up in heaven.” He is quick to state that he can see it day or night while Tristram cannot see it at all. Dagonet places himself in rarified territory by stating that the star “makes a silent music up in heaven, / And I, and Arthur and the angels hear, / And then we skip.” In short, Dagonet has become the one character left in Camelot who truly lives up to the ideals upon which it was founded. The bespoiled tournament, its flawed champion, and that champion’s uncourteous performance following the victory all serve to highlight the moral and philosophical fall of Camelot. When Arthur, who was away in battle during the tournament, returns to Camelot, he finds a hall not raucous with celebratory banqueting, but as empty as the moral coffers of his kingdom. Dagonet alone is there to greet him, and he morosely tells the soon to be fallen king that “I am thy fool, / And I shall never make thee smile again.”

Edgar Fawcett’s 1885 play, The New King Arthur: An Opera Without Music, maintains Tennyson’s vision of Dagonet as a fiercely loyal and perceptive character. That, however, is the lone connection between these two early works. Fawcett’s hilarious take on Camelot stands in stark opposition to the morose image of Tennyson’s Dagonet, weeping at the feet of a fallen king in a fallen court. The far more whimsical tone is clear from Fawcett’s tongue-in-cheek dedication to Tennyson, which includes lines such as “I have sung in my way, thou in thine. / I think my way superior to thine, / Yes, Alfred, yes, in loyal faith I do.”

The action of the play follows a series of plots by conspirators for Arthur’s throne. Lancelot, seeking the throne and a willing Guinevere, recruits Merlin to his cause by promising the wizard that he would make him Prime Minister in the kingdom to come. Meanwhile, Modred partners up with Vivien in their own attempt to win the realm by seizing Excalibur. While Lancelot and Modred plot for power, Guinevere and Vivien are after Merlin’s mythical face wash and hair dye. Guinivere particularly wants the face wash to ensure her status as the most beautiful woman in the kingdom, while Vivien longs for the hair dye, as she believes that, if only she were a blonde, she would be able to tempt a hilariously vain Galahad.

Amid all of this chaos and conspiracy stands Dagonet, who is oddly not a knight in this play. As in Tennyson, Dagonet is the only figure in Camelot loyal to Arthur and the founding virtues of Camelot. He alone is aware of the plots against the king, and does what he can throughout the play, including a scene where, in song, he calls Merlin a liar. As the play progresses, we see an odd juxtaposition of expectations. All of the usually serious Arthurian characters act like foolish caricatures of themselves, while Dagonet begins to demonstrate a far more serious, and occasionally ruthless, streak. After a conversation with the duplicitous Guinevere, he says in an aside, “If I but loved thy lord the less, fair Queen, / I’d show thee, who hast ever used me ill, / How fools can hate.”

Ultimately, Dagonet seeks to foil the plots of the conspirators, who planned to distract Arthur and then send Guinevere into a highly-secure vault to steal its contents—Excalibur and the mythical face-wash and hair dye. Dagonet steals the sword from Guinevere when she emerges from the vault, runs out and presents it, along with the truth about the conspiracy rampant in the kingdom, to Arthur. Arthur, however, immediately silences Dagonet, removing from him his fool’s privilege to speak, and banishes him as a traitor after the actual conspirators convince him that Dagonet was the true thief. Such an ending is both somewhat unfulfilling and all the more tragic, as it ensures that when Camelot does inevitably fall, Dagonet will not be there to stand with his king.

Since his revival by Tennyson and Fawcett, Dagonet has experienced a bit of a renaissance. Madison Cawein twice mentions the character, once in his 1889 “Accolon of Gaul” where Dagonet appears as part of a parade of Arthurian characters. He accompanied “a knight, steel-helmeted, a man of men, / Passed with a fool, King Arthur’s Dagonet, / Who on his head a tinsel crown had set / In mockery.” Cawein again referred to Dagonet, albeit tangentially, in his 1912 work, “The Poet, the Fool, and the Faeries.” F.B. Money-Coutts’ 1897 poem, “Sir Dagonet’s Quest” is essentially a retelling of Malory’s tale of Mark’s mistaking Dagonet for Lancelot. Ernest Rhys refers to Dagonet twice in his 1918 collection, The Leaf Burners and Other Poems. In “Dagonet’s Love Song,” oddly enough the one that doesn’t specifically mention Dagonet, Rhys offers a short poem with a thrice repeated refrain of “My soul, was she not fair!” Rhys offers a more direct take on Dagonet in the poem “La Mort Sans Pitie,” a call and response poem between Dagonet and Morgause, the evil mother of Gawain and Mordred. Dagonet asks who is at the door, and Morgause claims that it is only a shadow. Dagonet, not fooled, begins a lengthy stanza that almost resembles a fool’s take on an Anglo-Saxon boast, proclaiming the quickness and immortality of his wit, which, according to him, was born out of Eve’s laughter before the fall of man. More recently, Dagonet has appeared as a character in Alfred Angelo Attanasio’s 1998 novel, The Wolf and the Crown, which tells the tale of Arthor’s first year on the throne. Attanasio’s book, part of a series, is a sort of mash-up of Arthurian legend and Celtic myth, situating “Arthor” as a reincarnation of Cuchulain. The Dagonet of Attanasio’s world is described as the “dwarf vagabond and gleeman of King Arthor’s court.”

While Dagonet appeared in various works, as noted above, most of his appearances centered on one of four key themes: his connection with Merlin, his fate after the fall of Camelot, the role of the fool, and his status as a knight. The odd connection between Merlin and Dagonet is best seen in Edwin Arlington Robinson’s 1917 Merlin and in Waldemar Young’s 1930 play, The Birds of Rhiannon. In Merlin, we see the closing days of a falling Camelot. Knights are taking sides, and all are expressing doubt over the future of the kingdom. Merlin had, ten years earlier, willingly gone off with Vivien. At the beginning of the text, Gawaine seeks out Dagonet, asking the fool what he sees when he looks on Camelot. They end up discussing rumors of Merlin’s return from Broceliende, with Gawaine showing the fool respect, referring to him often by his knightly honorific, and also, at times, envying Dagonet, saying “Or am I the fool? / With all my fast ascendency in arms, / That ominous clown is nearer to the King / Than I am.”

Dagonet’s closeness to the King is emphasized over and over again, as Arthur identifies only two of his train who can reach him in his despair—Merlin and Dagonet. Arthur describes Dagonet as “one / Whom I may trust with even my soul’s last shred” and he groups Merlin and Dagonet together as his inner circle, with the narrator saying, “If any, indeed, were near him at this hour / Save Merlin, once the wisest of all men, / And weary Dagonet, whom he had made / A knight for love of him and his abused / Integrity.”

When Merlin finally does arrive back in Camelot in the seventh section of Robinson’s poem, he disguises himself from the likes of Bedivere and Gawain, revealing himself only to Dagonet, calling him “Sir Friend, Sir Dagonet” and asking the fool to pray for him. Dagonet, expressing a desire to leave Camelot’s corruption in order to live a simpler life, changes allegiences from Arthur to Merlin at the end of the poem. Both characters, realizing that they had done all they could for Arthur, leave Camelot together, with Dagonet realizing “he was Merlin's fool, not Arthur's now: / "Say what you will, I say that I'm the fool / Of Merlin, King of Nowhere; which is Here. / With you for king and me for court, what else / Have we to sigh for but a place to sleep?”

Robinson situates Dagonet as a proud figure. Merlin witholds his pity from Dagonet, stating “…you were never overfond of pity. / Had you been so, I doubt if Arthur’s love, / Or Gawaine’s, would have made of you a knight.” By the end of the poem, pity is all that either Dagonet or Merlin have to offer Arthur, king of a ruined Camelot. The pair, described throughout as the only two whom Arthur can really trust, depart Camelot together, an unlikely but not incompatible pairing.

A decade and a half after Merlin, Waldemar Young, a grandson of Brigham Young, penned a musical play exploring the connection between Arthur’s fool and his wizard. Young’s two-act play is particularly interesting due to the copious notes and details on the music. We know, for example, the names of the musicians who played each instrument, the names of the actors, and some of the story of the play’s creation and production. The first act of the play shows a straightforward, often amusing plot. Dagonet and Taliessin the bard, along with a group of lesser bards, are chasing the moon in their search for the land “beyond the farthest hill,” a quest begun based on Merlin’s solemn council. According to Merlin, beyond the farthest hill, the bards would “find what we desire, / What each of us, in all a wishful world, / Would most desire.” When Sir Kay arrives and tells the bards that they have a duty to return to their king—a false tale, as Arthur has already been killed—only Dagonet remains desirous of chasing the moon. This sets up the recurring theme in the play of the conflict between dreams and duty. As the other bards file off stage, the play takes a much darker turn. Kay looks at Dagonet with murder in his eyes, and Dagonet deciding to die fighting, is quickly run through on Kay’s sword. The first act ends with Kay laughing as he exits, and Dagonet’s crumpled body sitting motionless on the stage.

Act Two opens on “The other side of the hill,” where three spirits—of Poetry, Music and Philosophy—speak and sing. Dagonet encounters Merlin, and is aware that both he and the wizard have died. As the spirits prepare for the arrival of a king who will rule eternally, Merlin reveals that he knows Dagonet’s deepest desire—to be a king himself. The play begins to wrap when Arthur, also dead, arrives on “the other side of the hill” and reveals that he also had a secret unspoken desire—to be a singer, for he had taken such joy from his bards. Arthur vacates his throne, choosing his dream over his kingly duty. He offers his sword to Dagonet, who ascends the throne and is crowned, robed and sceptered by the three spirits.

Both Robinson and Young depict a far closer relationship between Dagonet and Merlin than is found elsewhere. Dagonet, fiercely loyal to Arthur in just about every modern text, opts to abandon Arthur in order to follow the counsel of Merlin (in Young) or to follow Merlin himself (in Robinson).

Another theme to be found in the various modern portrayals of Dagonet is that of his ultimate fate. Thanks in large part to Tennyson, Dagonet is often connected to the fall of Camelot, usually standing alone as the last believer of a failed ideal. Dagonet is often shown as a figure who was abused in life only to stand victorious, outshining the rest at his death. This can be seen, albeit tangentially, in Bliss Carman’s 1912 poem, “The Last Day at Stormfield,” a tribute to Mark Twain. Published two years after Twain’s death, the poem contains numerous details referring to the author, including the title, as “Stormfield” was the name of Twain’s home in Redding, Connecticut, and it was there that he died in 1910. The poem laments the passing of an unnamed jester, who was “Fearless, extravagant, wild, / His caustic merciless mirth /Was leveled at pompous shams.” The poem ends by drawing a parallel between the unnamed jester (Twain) and the only court Fool cited by name—Dagonet. The poem differentiates the unnamed jester from other deceased authors—including Chaucer, Shakespeare, Molière and Cervantes—stating that instead, he “listens and smiles apart, / With that incomparable drawl / He is jesting with Dagonet now.” Though the poem is ostensibly about Twain, it also elevates the stature of Dagonet, taking him from a deformed mortal fool and transforming him into the equal (or better) of the best wits of many ages.

While Carman showed the rise in Dagonet’s reputation after the character’s death, Muriel St. Claire Byrne offered a potential look at the actual moment of his death in her 1917 poem, “Dagonet, Arthur’s Fool.” Byrne’s short poem laments Dagonet who, with Camelot falling, did not stand on the sidelines, but “shocked and crashed with the rest / … / When Arthur fought in the West.” Byrne shows a Dagonet mangled and left to die alone in the mud and the rain, when none other than Mordred himself stumbles across the fool. Mordred, said to hold a deep hatred for Dagonet, “swung a crashing blow / Right on the mouth of the fool.” Dagonet, showing a bravery that would have been inconceivable in the medieval versions of the character, clings to his sense of mirth in the face of death, as he “lifted his bleeding head, / Dazed for a moment’s space; / Then Dagonet, Arthur’s fool, / He laughed in Mordred’s face.”

William Bacon Scofield offers yet another take on the end of Dagonet in his 1921 “A Forgotten Idyll.” Scofield depicts a Camelot years after Arthur’s fall, as a place cursed by “a plague of evil things,” with the ideals of Arthur and the Round Table forgotten by a series of “petty lords.” This chaos was only ameliorated with the arrival of a youth so valiant and skilled that people thought him to be the son of Launcelot and Guinevere. They shortly made him king, and even called him Arthur. The new Arthur purified the land and cast out evil, in emulation of his namesake. He personally defeated Ulrich, the “wild earl,” in battle. After his defeat, Ulrich professed false loyalty to Arthur, and immediately began sowing seeds of discontent. A secondary plot centers on Ulrich’s romantic failures, specifically his rejection by a woman named Thelda. As revenge on her for his rejection, he accuses her of plotting against Arthur, knowing that she would not find any knight who could face him.

Thelda, in her imprisonment, had only one visitor—“old Dagonet” who was “sole survivor of those glorious days / When knighthood meant the service of the Lord.” Thelda declares herself the daughter of one of the old Knights of the Round Table (and not the least—though she never specifies who it is). Dagonet wishes he could change places with her, as his body is as much a prison as her cell, and he longs to return to old Arthur and make him laugh. Dagonet suggests that she call upon the Forest Knight, unknown to all save himself and Ulrich, and she agrees. The scene closes with Dagonet capering as he used to in his youth, and singing a cryptic song: “The day is all too short, the night too long, / And one shall win the fight and one shall fall, / Who wins shall lose; the loser shall win all."

The poem closes with the joust between Ulrich (dressed all in black) and the Forest Knight (dressed gaily in elements of nature—with ferns and lilies taking the place of actual armor). Ulrich very quickly defeats the Forest Knight, revealed to be none other than old Dagonet, lightly armed in leaves, twigs and flowers. Dying, he whispers in Arthur’s ear a request to let Ulrich go if Thelda is spared. Touched by Dagonet’s “valiant deed,” Ulrich confesses his false accusation and offers his life. Arthur, per Dagonet’s prior urging, banishes Ulrich, who is seen no more. This version of Dagonet’s end shows him as the only survivor of Camelot, and situates that survival as a sort of prison sentence. His final sacrifice is redemptive in nature, as he redeems not only the lives of Ulrich and Thelda, but also the values of old Camelot.

The vast majority of modern Dagonet portrayals have dealt in some way with the questions of his professional duality. Dagonet is a court fool, but he is inexplicably also a knight. This conflict in role has led many a writer to explore just what it means for him to be a fool and what his role as a knight actually entails. Ralph Erwin Gibbs, in his 1903 poem “Sir Dagonet’s Song,” shows a Dagonet who playfully embraces his fool’s motley. The poem’s cadence has the feel of a drinking song, and it features Dagonet encouraging the reader to live life for the moment. Gibbs plays on the sense that it is good for the fool to be “cracked” in the head, as it lets the sadness out and allows him to forego such ridiculous things as jousting for honor. Dagonet also blurs the lines between the various social spheres, by amalgamating the different titles of the court, since he is called the “Fool Knight” and “Sir Fool.”

Other writers have explored Dagonet’s role as the fool in a more philosophical light, and they situate the character as a figure to be respected for his wisdom and rhetorical power. Corson J. Miller wrote a pair of poems, “Dagonet Makes a Song for the King” in 1923, and “Dagonet Makes a Song for the Queen” in 1934. The earlier poem features Dagonet mixing gibberish with laments—about people who ignore the Fool’s wisdom—and warnings to the King to beware because “Good friends are few.” The later poem is a bit darker in tone, as it points out the ephemeral nature of life and worldly privilege. Each stanza of “Dagonet Makes a Song for the Queen” features a culminating line that begins with “Sing hey diddle diddle, sing hi diddle diddle” and ends with deathly images, like “for the dead that live though slain.”

Susan Spilecki’s 1995 “Dagonet the Fool” offers a distinctly more powerful version of the character. In Spilecki’s poem, Dagonet is confident to the point of being arrogant. In the first stanza alone, he refers to the other knights as “those lackeys at the court,” claims that his mother had “the Second Sight,” and that he can sometimes “see more than Taliesin the bard / And Merlin the enchanter can, combined.” He goes on to state that, when he juggles, the blur of his multi-colored balls creates a rainbow mirror through which he can look into the future. During one such look into the future, he sees the fall of the king and is so alarmed that he drops his balls. The other knights mock him and Arthur patiently forgives him, but only Dagonet knows what he saw—a vision of the end of Camelot. At the close of the poem, Dagonet asserts that he would rather be himself than Lancelot, since it would be better to be “a fool in small things all my life / Than a great lord who, with one folly alone, / Casts all he loves to ruin at life’s end.”

The duality of Dagonet’s role is often shown by emphasizing the contrast between his wisdom, which allows him to see the fall of Camelot, and his social status, which renders him powerless to prevent that fall. Oscar Fay Adams’ 1886 poem, “The Return From the Quest,” depicts Arthur in a state of melancholy over the absence of his knights, who have gone questing for the Grail. Dagonet tries to cheer his king, to fulfill his role as the fool, but he ends up only perpetuating Arthur’s melancholy. Whether through his songs or his jests, Dagonet ends up repeating the same message that the days of joy are numbered and “high hopes—high deeds—we hope but while we may.” Dagonet, who calls Arthur his “brother fool,” sees that Camelot is slowly crumbling, and this awareness conflicts with his desire to cheer the king.

H.T.V. Burton’s 1921 poem, “Sir Dagonet,” features the titular character lamenting that his master, Arthur, has succumbed to rage and is implacable. The fool is no longer able to produce a smile from his King, which renders him completely powerless. Dagonet wishes that he could be his master’s “littlest page” so as to actually be able to do some valiant act to smite Arthur’s enemies and thus placate his rage, but he ends by lamenting that he remains just a fool. Dagonet’s lack of power was also the topic of C.W. Bailey’s 1929 play, King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. This short play, part of a collection of short dramatic scenes intended for young actors, essentially offers a stage version of Tennyson’s Idylls, even lifting verbatim Dagonet’s final line of “I am thy fool / And I shall never make thee smile again.”

Finally, some modern treatments of Dagonet view his role as the fool as a transcendent one. Ernest Rhys explored this notion in a pair of 1905 poems, “The Song of Dagonet” and “The Two Fools (Dagonet’s Song).” “The Song of Dagonet” takes the form of a bit of poetic advice to Arthur’s fool. The speaker refers to Dagonet as “heaven-born fool” and puts him above the other Arthurian knights, arguing that any man can fight and die, but “Only one can play the fool--Dagonet.” In “The Two Fools (Dagonet’s Song),” the speaker, presumably Dagonet, sets himself in opposition to a lesser fool, frequently reminding the reader that his folly is “of heaven” while his oppenent’s was “Love’s melancholy.” One of the hallmarks of the poem is the speaker’s insistance that he is empowered by “Heaven-sent folly.”

More recently, Dagonet has appeared in the final segment of William Andrew Hughes’ MFA thesis, Merely Celestial: A Creative Poetry Manuscript. Dagonet features in the final segment, titled “The Book of the Book” which depicts a quest undertaken by four knights—each representing one of the four dialects of Old English—Dagonet, and Yogh, an archetypal fifth knight who was “not meant to embody any dialect” (Hughes xviii). The oddly out of place Dagonet is described as a fallen character, “with red nose and motley under his armor” (53). He commands a regiment of a dozen turkeys, and his name, though once “heralded with much mirth and merriment,” was now brought low, as he was the only figure not “taken to jest and gesture” and he was often incapable of speech (53-54). Ultimately, the quest ends with everyone dead except for Dagonet and Yogh, who both encounter the writer of the Book. When the writer asks Dagonet his name, the narrative part of the poem ends with the line “Dagonet spoke” (76). The text that follows is made up of a series of amusing passages reflecting the corruption of language, broken into various sub headings such as “LinguisticCorruption” and “PointlessIntertextuality.” The fool and Yogh are the only survivors of the old language, and Dagonet is situated in a transcendent way, as the shaper of the language to come.

The move by Malory and the writers of the prose Tristan to transform the idiotic knight of the earlier tales into a knight/court fool hybrid has been an area of interest in nearly every modern representation of Dagonet. These modern representations focus on whether or not he was a real knight, who it was who knighted him and the implications of that role. In the previously mentioned play by Waldemar Young, The Birds of Rhiannon, the legitimacy of Dagonet’s knighthood is questioned by Sir Kay. When Dagonet sees Kay approaching their group, he calls out “Comrades in Arthur’s name, my fellow knights!” (emphasis mine). Kay’s response lacks the knightly honorific that Dagonet feels he has earned:

KAY

Dagonet!

DAGONET

Sir Kay forgets his courtesy.

I am Sir Dagonet, to knighthood sworn.

KAY

The King did jest the day he dubbed ye knight.

Dagonet takes issue with Kay’s assertion and proceeds to address Kay without his title, which clearly grates on the seneschal. The exchange serves to highlight a number of issues commonly seen in Dagonet stories—particularly whether or not the fool is a real knight, and who it was who knighted him.

In Oscar Fay Adams’ 1906 poem “The Pleading of Dagonet,” the fool is depicted as a “bitter-tongued yet not unkindly dwarf, / Dark-haired and swart of hue, one Dagonet, / Who oft at royal banquets flasht his wit.” Here also, Dagonet is depicted as a knight, with the speaker referring to him as “Sir Dagonet” and the Queen Margaret referring to him as “Sir Fool.” What is unique about Adams’ take on Dagonet is that he is not in the court of Camelot. The poem puts Dagonet in the court of King Ban of Benwick and his jealous wife Margaret. The plot focuses on Dagonet’s use of his wit to reconcile the court at Benwick, and notes that Dagonet “in the next year went / As sign of friendly bonds between kings / To dwell at Arthur’s court in Camelot.” Not only does this text establish Dagonet’s origin as Ban’s palace at Benwick, but curiously, Dagonet is already a knight, long before he arrives at Camelot.

In the same year as Adams’ poem, Stark Young published Guenevere: A Play in Five Acts, which included a representation of a Dagonet who is clearly not a knight. In the Dramatis Personae, he is listed merely as “the queen’s page” and he is repeatedly referred to as “boy” throughout the text by multiple characters. This Dagonet is loyal not to Arthur or Merlin, but to Guenevere. He runs her errands throughout the play, and even accompanies her to the convent at Boscastle after Mordred springs his trap.

Gerald Lovell commented on the ephemeral nature of Dagonet’s knighthood in his somewhat morose book, Arthurian Epitaphs and Other Verse. Lovell’s text includes a series of epitaphs, similar in style to The Spoon River Anthology, for major Arthurian characters. Dagonet’s epitaph is quite short:

Dagonet

I was a Fool, and ever Fool shall be.

I was a Knight: my knighthood dies with me.

The epitaph demonstrates the limitations of Dagonet’s specialized knighthood. His knighthood is not something that could be inherited by any potential children. It can be read as a sign that Dagonet’s knighthood is not one of lineage or nobility, but rather an honor based on his individual quality.

Two Dagonet texts, Morley Steynor’s 1909 Lancelot and Elaine: A Play in Five Acts and Sophie Jewett’s 1905 “The Dwarf’s Quest: A Ballad,” depict a Dagonet who is himself conflicted about his dual role of Fool and Knight. In Steynor’s play, Dagonet is again situated as both a legitimate knight and a court fool. In fact, he takes professional pride in his status as the fool, chastising the serving maid when, intending to compliment him, she states that “King Arthur’s jester is no fool.” Though Dagonet is much beloved in this play, with even Guevevere saying that “beneath that motley garb / There beats the kindest heart in Christendom,” he remains unhappy with his role. When Guenevere urges Lancelot to enter a tournament in disguise, Dagonet goes with him, hoping to win some acclaim by proxy. The pair are assaulted on their way to Camelot, and Lancelot is badly wounded. As a hermit tends to Lancelot’s wounds, Dagonet returns to the battle site for Lancelot’s sword and notes the many dents and scratches on it. He—in his own imagination—ponders his own “heroic” role in the fray, and is shocked to find that his own shield and helmet are still in pristine condition. He pleads “for a wound to speak for my valour! Oh for a scratch to justify my existence!”

While Dagonet wishes for more battlefield honor to justify his existence as a knight, he seems to wish away the very skill that makes him such an effective fool. In Act 4, Dagonet has a conversation during a banquet, regarding the true nature of the job of the fool. He explains that it is “my profession to be light of heart / When all around are sorrowful, to laugh / When I am sad myself.” Since the banquet was away from Camelot, nobody knew—until he told them—that he was a fool, and he expresses a value in that anonymity, since “Here I’m allowed / To frown and fret and fume just as I please. / At court I must be merry: here I’m free / To revel in the luxury of grief.” Steynor’s depiction of Dagonet is a rather dour take on the character’s duality. His wit and skill as a fool bring joy to others and accolades to himself, but they bring him no joy. He would much rather be known as a knight, but he lacks the requisite skill.

Jewett’s poem also depicts a Dagonet who inwardly wished for more skill as a knight. He watches as a procession of knights leave Camelot for the Grail quest. Most of the knights “saw him not” and Dagonet “hoarded, in his pain, / A smile from sad Sir Lancelot, / Three sweet words from Gawain.” Dagonet curses the Grail because he was too “crooked and weak” to seek it himself. Though his body is frail, Jewett depicts him as inwardly strong, as “ice and flame were in his breast; / He hid his curling lip, / And wept for fierce desire to quest / With the great Fellowship.” Dagonet prays, and he is answered by a voice that tells him that a vision of the Grail is still to come for both himself and for Galahad. When Dagonet again laments his unworthiness for having cursed the Grail, the voice reassures him, telling him “Thy cursing lips I do forget, / Because of thy heart’s prayer,” further contrasting his flawed exterior with his virtuous inner qualities.

The day after the vision, Dagonet leaves Camelot to quest for the Grail. He soon finds Lancelot, gravely wounded, at a crossroads. Suddenly, the pair is bathed in light and four maidens appear, one holding the Grail. Selflessly, Dagonet prays for the Grail to heal Lancelot, saying “Thou to the fool art good, / Be gracious to the knight.” With Lancelot healed, Dagonet returns to Camelot, keeping his experience to himself. As knights return in defeat, Bors eventually tells of Galahad’s achievement of the Grail. Dagonet’s quest is neither known nor celebrated, as the poem notes that “For Galahad brave eyes were wet, / And gentle Percivale; / None ever heard how Dagonet / Achieved the Holy Grail.” Jewett’s poem essentially offers a more upbeat take on Dagonet’s duality. In Steynor’s play, Dagonet wishes for knightly skill and laments his role as the fool, but he cannot escape his station. In Jewett’s poem, Dagonet wishes, even more than in Steynor, for the glory of the quest, but the quest itself teaches him that he was already possessed of an inner quality that most of the knights of the Round Table lacked.

Visual Dagonets

While Dagonet has not often been a subject for artists, he has been included in a handful of illustrated editions, often by artists who were giants of book illustration. One of the earliest of these illustrations came in the 1872 edition of Tennyson’s “The Last Tournament.” Hammatt Billings, a Boston artist best known for providing the original illustrations for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, contributed a drawing of “Dagonet Dancing Before Tristram.” The drawing shows a small, mischeivous-looking Dagonet in full fool’s regalia, mocking a clearly annoyed Tristram.

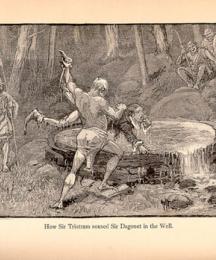

The 1880 edition of The Boy’s King Arthur provided an illustration titled “How Sir Tristram Soused Sir Dagonet in the Well” by American artist Alfred Kappes. Kappes has been described as “a man of rare originality and the finest artistic sensibility” who has fought “the battle of life…without allies” (Alfred 75). His illustrated edition of The Idylls of the King was described as “the most splendid art work ever given out in America” (Alfred 75). His Dagonet depicts the scene from Malory, with a powerfully-built Tristram throwing Dagonet into a pool of water as a gathering of clearly delighted shepherds watch in the background.

Two visual representations of Dagonet were printed in 1912. The Story of the Idylls of the King Adapted from Tennyson with the Original Poem featured the illustration “I Shall Never Make Thee Smile Again” by M.L. Kirk, a book illustrator best known for her contributions to Heidi. Kirk’s illustration shows Arthur, clutching his heart, with Dagonet on the floor, hugging Arthur’s leg in a child-like manner. F. A. Fraser, an artist best known for his meticulous illustrations in the Household Edition of Dickens’ Great Expectations, contributed a sketch titled “King Mark Pursued by Dagonet” to King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table. Of all the visual Dagonets, this one is perhaps the least clear. Though it depicts a horse chase, with two armed knights pursuing a third, there is no clear visual indication other than the title of the image that one of the two giving chase is Dagonet.

Arthur Rackham, a leading British book illustrator who lent his work to a number of notable texts, including Cinderella, Aesop’s Fables, A Christmas Carol, Gulliver’s Travels, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and several editions of Shakespeare’s plays, provides a rather unique visual take on Dagonet in his 1917 illustration, “Dagonet, King Arthur’s Fool.” The image, included in The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, Abridged from Malory’s Morte D’Arthur, has a style reminiscent of a caricature. Dagonet appears cartoonishly thin and frail, and everything from his cap, bells, bauble, and shoes are delightfully larger than one would expect on such an emaciated form.

Pop Culture Dagonets

Dagonet has sporadically appeared in popular culture, and surprisingly, most of those appearences are fairly recent and have little to do with any of the character’s previous iterations. One of the older popular references is a rare musical score by composer Leslie Fly. Fly was one of a number of in-house composers writing pieces for the education market for the Forsyth Bros. publishing house, and she frequently produced pieces with literary connections. Her piece “The Court Jester (Sir Dagonet)” was included in her 1923 collection, King Arthur’s Knights: 9 Miniatures for Pianoforte. Dagonet’s inclusion in such a work is in itself somewhat odd. Of the nine compositions in this work, five make direct reference to specific Arthurian characters--Lancelot, Elaine, Arthur, Galahad and Dagonet. It is surprising that Dagonet was included over better known characters like Guinevere, Gawain, Mordred or Merlin. Out of curiosity, one of the staff members at The Camelot Project played the piece on the piano, remarking that, like the fool himself, it had the tendency to jump around, never quite maintaining a melody.

More recently, Dagonet has appeared in some rather unexpected places, including a 2010 episode of the cartoon Ben 10: Ultimate Alien. The episode, titled “Andreas’ Fault,” featured a character named Sir Dagonet, a “Forever Knight intelligence officer.” In the narrative of the cartoon, the Forever Knights are a recurring group of antagonists generally characterized by vague medieval stereotypes—one faction claims to seek to protect the Earth by preparing to slay a dragon, and they wear technologically advanced yet archaic looking plated armor with medieval trappings. The group follows a “Forever King,” but there is apparently some dispute and conflict over who the authentic Forever King should be. Though steeped in superficial Arthurian details, these characters had almost no connection to any specific Arthurian texts. Sir Dagonet is the first and, to date, only Forever Knight named after one of the medieval Arthurian characters.

The plot of the episode involved a rodent-creature named Arjit taking over a faction of Forever Knights and using them to commit petty crimes. The show’s protagonists—Ben 10, a boy who can assume alien forms, his sister, who has magical abilities, and Kevin 11—seek to intervene in Arjit’s scheme. In the midst of that conflict, Sir Dagonet, voiced by Greg Ellis, arrives. When he announces himself, using his knightly honorific, the other Forever Knights react in awe and respect, whispering amongst themselves. It becomes clear that the rogue faction of Forever Knights will now be taking orders from Sir Dagonet, and this ultimately leads to the downfall of Arjit, who even refers to Dagonet—often historically portrayed as a dwarf—as “big fella.” Beyond the name, there are hardly any parallels between the cartoon character—who has yet to appear in another episode—and the Arthurian knight, but it is curious that Dagonet, of all characters, was the one the show’s writers—James Krieg and Ernie Altbacker—opted to use.

Dagonet is also shown in a less than familiar form in the 2004 film King Arthur by director Antoine Fuqua. Fuqua attempted to offer a “demystified take” on the Arthurian legend, though it has not generally been viewed as historically accurate. In the film, Dagonet is portrayed as an axe-wielding, more than capable warrior. Actor Ray Stevenson—best known for his role as Volstagg in Thor and as Frank Castle in Punisher: War Zone—who has carved himself a niche playing warriors, played Dagonet. There is no mention of his being Arthur’s fool. Instead, the role is simply that of yet another valiant knight of the Round Table who ultimately sacrifices his life to save his companions.

Dagonet has recently appeared—albeit in name only—in comic book form. The Order of Dagonet is a comic book by writer Jeremy Whitley and artist Jason Strutz published through Action Lab Comics in late 2012. The first issue opens in a scene more reminiscent of Shakespeare than Malory. A group of clear-cutters bring down a massive tree, which reveals an ancient portal from which Titania and Oberon spring forth. Puck arrives soon after, and immediately decapitates an actor playing the role of Puck during a production at the Globe in front of Queen Elizabeth II. The story then begins to offer vignettes introducing the reader to characters who are fairly obvious analogues for famous British entertainers—Ozzy Osbourne, JK Rowling, Ian McKellen, and Elton John. Soon, these celebrity analogues are spirited away and, halfway through the issue we learn that they were gathered together by Merlin, who refers to them as “Knights of England.” By the end of the first issue, we learn that in this version of England, there is a ceremonial order of knights called the Order of Dagonet, reserved for those whose contribution to the kingdom is in the entertainment field. The first issue offers a fictional, Wikipedia-style page detailing the history of the “Order of Dagonet” and its connection to Arthur’s fool. The story proceeds as Merlin informs these pampered, temperamental, and battle-incompetent celebrities that they are indeed knights of England, and England needs them to act against the Shakespearean faeries.

Critical Dagonets

While Dagonet has enjoyed several extended periods of creative attention, he has been almost completely neglected when it comes to scholarly attention. Most scholars mention him only in passing, as a supplementary part of a larger argument. Robert L. Patten’s article, “The Contemporaneity of The Last Tournament,” mentions Dagonet only briefly, discussing the power of music and the conflict between the songs of Dagonet and Tristram as “framing” the episodes of the fall of Camelot (260). The main goal of Patten’s work is to discuss the unique place of The Last Tournament, due to its status as a late addition to the Idylls and the fact that it was the only Idyll first published in a periodical. Patten uses this more traditionally serialized venue to read elements of national history, Tennyson’s personal history, and contemporary events, including the changing role of women in marriage, issues of war, fidelity, faith, and science within The Last Tournament and the Idylls in general.

Similarly, Don Richard Cox’s article, “The Vision of Robinson’s Merlin,” briefly mentions Dagonet while largely focusing on the structural elements of the poem. For Cox, the characters in Robinson’s narrative are all “straining to see something…seeking a something from beyond themselves which will help order and explain their lives” (499). Cox describes a power dynamic wherein each character looks to the person above him for that vision—Merlin looks to Vivian, Arthur looks to Merlin, Camelot turns to Arthur, and so forth. Ultimately, Cox argues, “what Merlin comes to realize is that although everyone is certain the person immediately above him in Camelot’s chain of being has an answer, no one in fact does” (501). When that way of looking at the world fails, Cox suggests that Merlin and Dagonet respond by re-creating themselves at the end of the poem. Cox de-emphasizes Dagonet’s prominent role in that re-creation, and thus, his article focuses far more on Merlin than it does on Dagonet.

Even when an article does focus on Dagonet, it often strays from that focus. This is the case with Mary Lascelles’ article, “Sir Dagonet in Arthur’s Show.” Lascelles uses seemingly disparate information about Dagonet in order to reach a conclusion—that there is a parallel between Falstaff and Sir Dynadan due to the fact that both are “loyal and disengaged” (154)—that has very little to do with Dagonet. While Lascelles’ conclusions seemed somewhat distanced from her methodology, her methodology itself is fascinating. She tracks, and puts into chronological order, the various early modern references to Dagonet. She first notes a number of references to Arthur and Malory that did not include Dagonet (Mulcaster’s Positions, Richard Robinson’s list of Arthurian knights, Jonson’s Tale of a Tub), and then suggests that Justice Shallow creates the role of Dagonet in King Arthur’s show in 2 Henry IV. She suggests that Jonson, in Every Man Out of his Humour mentions Dagonet in direct acknowledgement of Shakespeare’s play, and she argues that by the time Cynthia’s Revels is written, Dagonet has been reduced to “a nickname for any fool or fop.”

Interestingly, one of the most thorough treatments of Dagonet is also one of the most recent. Gergely Nagy’s 2004 article, “A Fool of a Knight, a Knight of a Fool: Malory’s Comic Knights,” looks at three of Malory’s comic characters in order to demonstrate how those characters serve to reinforce the knightly discourse by means of poor example. Nagy focuses his discussion on Kay, as the knight made foolish by pride; Dinadan, as the jester within the knightly system; and Dagonet, as the fool made knight. Nagy is careful to distinguish between mere humorous moments, such as the scene where Sir Belleus accidentally gets into bed with Launcelot and begins kissing him, and the kind of humor that can “comment on knights and knighthood” (Nagy 61).

Foundational to Nagy’s thesis is the understanding that, true to the romance genre, it had to be “knights who supply the comic discourse” which thus situates such humor as standing in “clear and direct opposition to the ‘serious’ discourse represented by the ‘tragic knights’” (60-61). Nagy argues that Dagonet, as a domestic knight, would be wholly incapable of winning fights, and that his inevitable losses provided “great amusement for other knights and all the court” (63). Those same characters who laugh at Dagonet’s failings, however, also show him great love. Nagy highlights the fact that Dagonet is “a favorite of the entire court [and] the best fellow” and then contextualizes this praise by showing that terms such as “fellowship” and “fellow” are “emotionally highly charged words for Malory, meaning more than mere companionship” (63-64). Ultimately, Nagy argues that Dagonet is acceptable as a knight because he “knows his place perfectly well” and he succeeds as a comedic commentary on knighthood precisely due to “the serious distance between his two roles, the household knight and the knight-errant” (64).

Conclusions

Dagonet has been many things during his more than 800 years of existence. He has been a foolish knight, an able administrator, a mangled dwarf, a musician, a court fool, a mystic, a battle-hardened warrior, and an image of loyalty. Though created as a cowardly knight, the prose Tristan and later Malory transformed Dagonet into a court fool who was also a knight, and this unlikely combination has captured the interest of some of the greatest poets, playwrights and illustrators of the last 500 years. Though Dagonet has received scant critical attention, he serves as an interesting barometer of our historical understanding of the court fool. When the prose Tristan and Malory defined him as such, the fool was largely present strictly for entertainment. With the arrival of Renaissance drama, the literary court fool grew to be a wise, advice-giving figure. As the role of the fool changed, Dagonet changed along with it. A character initially created to be abused for his idiocy grew into a much loved confidant of the Round Table, achieving the Grail, seeing the future, and—without fail—standing by his king.

Note: Several of the texts mentioned above are available in full text on the Camelot Project. Those texts have been linked. The following Works Cited reflects those titles mentioned that are NOT currently available on the Camelot Project. Also, special thanks to my colleagues Laura Whitebell and Kyle Huskin for their translation help with the Guiron le Courtois and the Le Roman De Tristan en prose. I have no French, and they were generous enough to share theirs.

“Alfred Kappes, Painter and Illustrator.” The Art Union. 2.4 (1885): 75. JSTOR. Web. 24 Oct. 2013.

“Andreas’ Fault.” Ben 10: Ultimate Alien. Cartoon Network. 4 June 2010. Television.

Attanasio, A. A. The Wolf and the Crown. New York: HarperPrism, 1999. Print.

Cawein, Madison. The Poet, the Fool, and the Faeries. Boston: Small, Maynard and Company, 1912. Print.

Cox, Don Richard. “The Vision of Robinson’s Merlin.” Colby Library Quarterly. 10.8 (1974): 495-505. Print.

Guiron Le Courtois: Etude De La Tradition Manuscrite Et Analyse Critique. Ed. Roger Lathuillere. Geneve: Librairie Droz, 1966. Print.

Hughes, William Andrew. Merely Celestial: A Poetry Collection. Diss. University of Massachusetts Boston, 2011. Ann Arbor: UMI, 2011. AAT 1494038. Print.

King Arthur. Dir. Antoine Fuqua. Perf. Clive Owen, Ioan Gruffudd, Ray Stevenson. Touchstone Pictures, 2004. DVD.

Lacy, Norris J. Ed. Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation. Vol. 2. Trans. Samuel N. Rosenberg and Carleton W. Carroll. New York: Garland Publishing Inc, 1993. Print.

Lascelles, Mary. “Sir Dagonet in Arthur’s Show.” Shakespeare Jahrbuch. Hermann Heuer, Wolfgang Clemen and Rudolf Stamm, Eds. Heidelberg: Quelle and Meyer, 1960. 145-154. Print.

Lovell, Gerald. Arthurian Epitaphs and Other Verse. London: Mitre Press, 1976. Print.

Malory, Thomas. The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. Ed. Eugene Vinaver. 3 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990. Print.

Nagy, Gergely. “A Fool of a Knight, a Knight of a Fool: Malory’s Comic Knights.” Arthuriana. 14:4 (2004): 59-74. Print.

Paton, Lucy Allen, ed. Les Prophecies De Merlin: Edited from MS. 593 in the Bibliotheque Municipale of Rennes. New York: Kraus Reprint Corporation, 1966. Print.

Patten, Robert L. “The Contemporaneity of The Last Tournament.” Victorian Poetry. 47.1 (2009): 259-283. Print.

Le Roman De Tristan en prose. Ed. Renee L. Curtis. Vol. 2 of 3. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1985. Print.

The Romance of Tristan. Trans. Renee L. Curtis. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994. Print.

Shakespeare, William. The Second Part of Henry the Fourth. The Riverside Shakespeare. 2nd ed. Ed. Herschel Baker et al. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997. 928-973. Print.

Welsford, Enid. The Fool: His Social and Literary History. New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1935. Print.

Whitley, Jeremy, and Jason Strutz. The Order of Dagonet. Durham: Firetower Studios, 2011. Web.

Read Less

Dagonet Makes a Song for the Queen - 1934 (Author)

La Mort Sans Pitié - 1918 (Author)

The Song of Dagonet - 1905 (Author)

The Two Fools (Dagonet's Song) - 1905 (Author)