The Isle of Avalon, most famous as the final resting place of Arthur in many stories and legends, has neither a fixed location nor a fixed description throughout the literary canon of Arthuriana. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s

Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136) is the oldest extant work including references to Avalon. He calls it

Insula Avallonis, refers to the island's alleged healing powers, and claims that Arthur’s sword was forged there. Geoffrey also refers to Avalon in his

Vita Merlini as the “Isle of Apples” (Insula Pomorum), an epithet rooted in Celtic, Greek, and Scandinavian mythological traditions in which apples frequently possess magical properties. In both the

Historia and

Vita, Arthur is transported to Avalon after being mortally wounded, in hopes that he will be healed on the isle (in the Vita Merlini by none other than Morgan le Fay, who is benevolent in earlier Arthurian legends). Support for the theory of Avalon’s Celtic origins stems in part from the folkloric tradition surrounding the Isle of Arran, located in the Firth of Clyde. It has been frequently likened to the island of Emhain Abhlach (“Emhain of the Apple Trees”), a place associated with the Irish sea god Manannan. As Mike Dixon Kennedy suggests in

Arthurian Myth and Legend, Geoffrey was likely inspired by the extant Celtic tradition of such a place. It should be pointed out, however, that no conclusive evidence can be found that directly traces the influence of Celtic mythology and legend to the genesis of Avalon and its literary tradition; while speculations abound and are, in many cases, well defended and researched, they cannot be proven. Regardless, Avalon is consistently represented as a mysterious and otherworldly place, even after being associated...

Read More

Read Less

The Isle of Avalon, most famous as the final resting place of Arthur in many stories and legends, has neither a fixed location nor a fixed description throughout the literary canon of Arthuriana. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s

Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136) is the oldest extant work including references to Avalon. He calls it

Insula Avallonis, refers to the island's alleged healing powers, and claims that Arthur’s sword was forged there. Geoffrey also refers to Avalon in his

Vita Merlini as the “Isle of Apples” (Insula Pomorum), an epithet rooted in Celtic, Greek, and Scandinavian mythological traditions in which apples frequently possess magical properties. In both the

Historia and

Vita, Arthur is transported to Avalon after being mortally wounded, in hopes that he will be healed on the isle (in the Vita Merlini by none other than Morgan le Fay, who is benevolent in earlier Arthurian legends). Support for the theory of Avalon’s Celtic origins stems in part from the folkloric tradition surrounding the Isle of Arran, located in the Firth of Clyde. It has been frequently likened to the island of Emhain Abhlach (“Emhain of the Apple Trees”), a place associated with the Irish sea god Manannan. As Mike Dixon Kennedy suggests in

Arthurian Myth and Legend, Geoffrey was likely inspired by the extant Celtic tradition of such a place. It should be pointed out, however, that no conclusive evidence can be found that directly traces the influence of Celtic mythology and legend to the genesis of Avalon and its literary tradition; while speculations abound and are, in many cases, well defended and researched, they cannot be proven. Regardless, Avalon is consistently represented as a mysterious and otherworldly place, even after being associated with Glastonbury in the twelfth century (a connection inspired by the “discovery” of Arthur’s remains there).

The rulers of Avalon differ according to the text in question. Morgan le Fay is, by far, most frequently identified as the ruler of the isle. In addition to appearing in Geoffrey’s Vita (but not, interestingly, in the Historia), she appears in Chrétien de Troye’s romances Eric and Enide and Yvain. In both, she is a healer and mistress of Avalon, though in Eric and Enide, the actual ruler of Avalon is said to be Guinguemar, and Morgan is simply referred to as his lover and later as a powerful healer. In this tale, Morgan calls the Perilous Vale – The Valley of No Return – her home, a location which might be a reference to Avalon. William of Malmesbury, however, states that Avalloch rules Avalon with his daughters, and Morgan is not mentioned at all by him. While rulership of the Isle is given little emphasis in later texts, Morgan is often tied to the place in some way, most typically by being one of those who brings Arthur to Avalon for healing after the battle of Camlann.

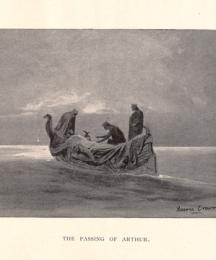

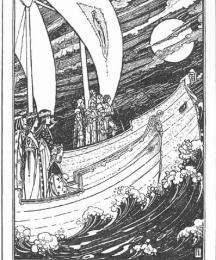

The Isle Avalon is, in fact, frequently presented (in medieval and modern texts alike) as a place of healing, particularly as the place where Arthur is taken after his mortal wounding. Initially, Avalon’s role seems to be one of preservation — though his wound is mortal, he will live as long as he remains on the Isle; in some cases his stay in Avalon must be permanent, while in other cases he need only remain in Avalon until his wounds are healed. In the Vita, for instance, Morgan tells Arthur upon his arrival that he will need to stay for a long time for his wounds to be properly healed. In later medieval Arthurian works, writers imply that Avalon is his permanent resting place, perhaps his place of death and burial. Thomas Malory in his Morte D'Arthur leaves room for either possibility in his description of Arthur’s departure:

“Now put me into that barge,” seyde the kynge.

And so he ded sofftely, and there [re]sceyved hym three ladyes

with grete mournyng. And so they sette he[m d]owne, and in one

of their lappis kyng Arthure layde hys hede. And than the quene seyde,

“A, my dere brothir! Why [ha]ve ye taryed so longe frome me?

Alas, thys wounde on youre hede hath caught overmuch coulde!"

And anone they rowed fromward the londe, and sir Bedyvere

behylde all tho ladyes go frowarde hym. Than sir Bedwere cryed

and seyde,

“A, my lorde Arthur, what shall becom of me, now ye go frome

me and leve me here alone amonge myne enemyes?”

“Comforte thyselff,” seyde the kynge, “and do as well as thou

mayste, for in me ys no truste for to truste in. For I must into the

vale of Avylyon to hele me of my grevous wounde. And if thou

here nevermore of me, pray for my soule!”

But ever the quene and ladyes wepte and shryked, that hit was

pité to hyre. And as sone as sir Bedwere had loste the

syght of the barge he wepte and wayled, and so toke the foreste

and wente all that nyght. (Malory, ed. Vinaver, p. 716)

As mentioned earlier, a tradition of Arthur’s death and burial at Avalon surfaced well before Malory, in no small part due to the alleged discovery of Arthur and Gwenevere’s remains at Glastonbury Abbey in the twelfth century. This area of England is still associated with the mythic isle; the flooding of the countryside during the summer used to create islands out of many of the higher hills. Roger of Coggeshall in his Chronicon Anglicanum (c. 1220) simply states that Arthur's body was found at Glastonbury which was formerly known as Avalon, the Isle of Apples. Gerald of Wales, writing in the late 12th century, argued against fantastic speculations about Arthur's remains in both his Liber de Principis Instructione (c. 1196) and his Speculum Ecclesiae (c. 1216). He asserts in the former that though " legends had fabricated something fantastical about his demise (that he had not suffered death, and was conveyed, as if by a spirit, to a distant place), his body was discovered at Glastonbury" (Liber, Sutton). In the latter, he speaks even more forcibly against the legends of Arthur's journey to Avalon, stating that "tales are regularly reported and fabricated about King Arthur and his uncertain end, with the British peoples even now contending foolishly that he is still alive" (Speculum, Sutton).

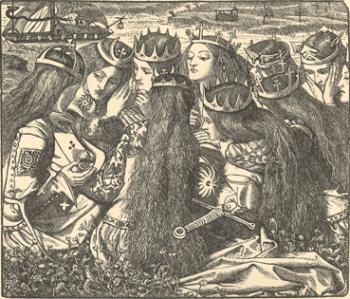

Despite Gerald's efforts to disavow the mythologizing of Avalon, the tradition of the Isle as the final resting place of Arthur and as a place of otherworldly mystery extends into the Arthurian "renaissance" of the 19th century, where many references to Avalon continue to be found. Many poems were written about Avalon during this time, several of which evoke the isle as an idyllic, healing place of eternal beauty. American poet Madison Julius Cawein, for instance, wrote a series of poems ("Unanointed" [1901], "Uncalled" [1902] and "Avalon" [1909]) in which the isle is consistently described in such terms. In "Uncalled," the poet imagines that he can see the beautiful Avalon but knows that it cannot be reached in this life. Other nineteenth-century poems that center on Avalon refer to it as the final resting place of Arthur. William Morris's "Near Avalon" is one such work, as is J. Arthur Blaikie's poem "Arthur in Avalon." Morris's imagistic poem describes the barge that carries Arthur to Avalon, and maintains, for all of its detail, a sense of the unknowable; the many details have an air of significance, but the reader is not necessarily aware of what they mean. Blaikie's poem was inspired by James T. Archer's painting, "La Mort d'Arthur"; it depicts the dying Arthur and the vigil kept by the four Queens who bore him on the barge to Avalon. Another poem of this period that evokes Avalon as Arthur's place of repose is Sally Bridges "Avilion" (1864), a dream-vision that includes a richly detailed account of the poet's metaphysical journey to the isle.

This interest in Avalon continued into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries due, undoubtedly, to the continued interest in the legends of Arthur in general. The idea of Avalon so popular in the 19th century has extended into these more recent literary traditions, though (as is the case with nearly all aspects of the Arthurian legend) authors continue to reinterpret and reinvent its popular modes of representation. Authors from Margaret Atwood ("Avalon Revisited" [1955]) to Salmon Rushdie ("Crusoe" [1990]) have evoked the idyllic landscape of Avalon, as have various singer/songwriters; both Cindy Lauper ("Sisters of Avalon" from the eponymous 1997 album) and Van Morrison ("Avalon of the Heart" from the 1990 album Enlightenment) have written songs about Avalon, both of which play on modern interpolations of the Avalon legend; Lauper's evokes some of the later twentieth-century representations of the Isle as a place of feminine strength, while Morrison's is thematically similar to the nineteenth-century poets such as Cawein, viewing Avalon as an internal spiritual goal.

Of all of the reinterpretations and evocations of Avalon, few have wielded as much influence in the late twentieth century as Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Mists of Avalon. Bradley plays with the tradition of Glastonbury-as-Avalon, describing a mystical divide between Christian and Pagan worlds, one in which Avalon exists in the same physical space as the Christian Abbey, though neither is more than peripherally aware of the other. In this work, the Isle is permanently inhabited by a company of priestesses and novices who wish to preserve the pagan traditions of Britain. The physical superimposition of Glastonbury Abbey upon Avalon indicates the waxing influence of Christianity and the waning power of the pagan religion. As the novel progresses, and as Christianity gains dominance, the magical mist around the isle continues to thicken, making it increasingly difficult for anyone except the initiated to find or enter into it.

Avalon has also been adopted and adapted by neo-pagan communities, some of which are more or less directly influenced by Bradley's work. "Officers of Avalon," is an online support group for neo-pagans in emergency services (website: http://www.officersofavalon.com). The Avalon Witchcamp and The Avalon East Pagan Gathering (in the UK and Nova Scotia respectively) are gatherings devoted to the communal celebrations of neo-pagans. The Avalonian Tradition is an entire branch of neo-paganism in and of itself. Jhenah Telyndru is the founder and "Morgen" of The Sisterhood of Avalon and Academic Dean of the Avalonian Theological Seminary, and has written several treatises on the tradition. On the Sisterhood of Avalon website (http://www.sisterhoodofavalon.org/), Telyndru denies any direct influence of Bradley's The Mists of Avalon, though there are numerous similarities between their respective works. Telyndru asserts, in the website's section entitled "The Avalonian Tradition," that

The power of Avalon, and indeed, the entire Arthurian legend, is not a fancy of days gone by. We need only look around us to find ample proof of its relevancy. Tales of Arthur, Morgan Le Fay and Merlin fill today's bookshelves. Psychologists, fantasy writers, Celtic scholars and personal growth proponents have all gained insight from this mythic cycle. There are many Wiccan and Pagan groups which draw heavily from the realm of Arthur and find a path of spiritual growth symbolized in the Quest for the Grail and the Code of Chivalry.

This organization is only one of many Avalonian groups, several of which apparently draw their authority from their location in Glastonbury a place that has become a virtual neo-pagan community in and of itself.

The name "Avalon" also appears frequently in popular culture, sometimes clearly evoking the Arthurian tradition directly, while at other times being used only as a name that evokes the mysterious. These references range from cars (Toyota's Avalon models, http://www.toyota.com/Avalon/), to nightclubs (http://www.avalonsacramento.com/html-home.html), to nudist colonies (Avalon, of West Virginia, featuring as its logo a nude figure curled up like an apple). Some play more substantially with the literary tradition of Avalon than others, but most of these appropriations seem to be more casual (though intriguing) evocations than anything else.

Avalon, as this brief chronological survey demonstrates, has been treated to a rich (if at times strange) and multifaceted development over the centuries. From the early portrayals as a mysterious place of supernatural qualities, to the wide-reaching array of modern permutations and adaptations, Avalon remains an ephemeral and mythic location that continues to inspire creative reinvention.

BibliographyDarrah, John. Paganism in Arthurian Romance. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell, 1994.

Dixon-Kennedy, Mike. Arthurian Myth and Legend. London: Blandford, 1995.

Lacy, Norris. The Arthurian Encyclopedia. New York: Garland, 1986.

Lacy, Norris and Geoffrey Ashe. The Arthurian Handbook. New York: Garland, 1988.

Nastali, Daniel P. and Phillip C. Boardman. The Arthurian Annals: The Tradition in English from 1250-2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Read Less