While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

The Legend of Yvain

a All images used on this page are taken with permission from the Robert Garrett Collection of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts No. 125. Manuscripts Division. Department of Rare Books and Special Collection. Princeton University Library.

1. Joseph P. Clancy, "Lament For Owain Mab Uriens." Medieval Welsh Poems. Dublin. Four Courts Press. 2003. 44.

2. Rachel Bromwich, "First Transmission to England and France." The Arthur of the Welsh. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1995. 272-79.

3. Annette B. Hopkins, The Influence of Wace on the Arthurian Romances of Crestian De Troies. Menasha, WI: George Banta, 1918. 98-100. Digitized in 2008 by Princeton University.

4. Hopkins, 99.

5. Roger S. Loomis, Arthurian Tradition and Chrétien de Troyes. New York, 1949. 269-331.

6. Gilbert D. Chaitin, "Celtic Tradition and Psychological Truth in Chrétien's 'Chevalier au Lion'." Sub-Stance 1:3 (1972): 63-76.

7. R.L. Thomson, "Owain: Cheedl Iarlles Y Ffynnon," The Arthur of the Welsh. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1995. 160-169.

8. William W. Kibler, Chrétien de Troyes: Arthurian Romances. New York: Penguin Group, 1991. Reprinted in 2004. 3-4.

9. F. M. Warren, "Some Features of Style in Early French Narrative Poetry (1150-70), Part I: Transposed Parallelism, or Repetition with Transposition of the Word at the Rhyme." Modern Philology 3.2 (1905): 179-209.

---, "Some Features of Style in Early French Narrative Poetry (1150-70), Part II: Direct Repetition of Words, Phrases, and Lines." Modern Philology 3.4 (1906): 513-39.

---, "Some Features of Style in Early French Narrative Poetry (1150-70), Concluded, Part IV [sic]: The Tirade Lyrique, or Couplets in Monorhyme." Modern Philology 4.4 (1907): 655-75. [Note: Printing error, later corrected in Modern Philology's own table of contents, lists "The Tirade Lyrique" as part IV; it is actually part III.]

10. W. W. Comfort, "Introduction", Four Arthurian Romances. Via Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/831/pg831.txt

11. There are many resources on courtly love. For an overview of scholarship, see Roger Boase, The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1977. Boase notes F. X. Newman (editor of The Meaning of Courtly Love. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1969) provides excellent bibliographies. Other scholars whose work has been helpful to this project Alexander Denomy and Jean Frappier.

12. Kibler, 302-303.

13. Tony Hunt, "Le Chevalier Au Lion: Yvain Lionheart." A Companion to Chrétien de Troyes. Eds. Norris J. Lacy and Joan Tasker Grimbert. New York: D.S. Brewer, 2005. 150-168.

14. Kibler, 307.

15. Marc Glasser, "Marriage and the Use of Force in Yvain" Romania 108 (1987): 484-502.

16. Kibler, 358.

17. Kibler, 360-361.

18. Tony Hunt, "The Lion and Yvain." The Legend of Arthur in the Middle Ages: Studies Presented to A.H. Diverres by Colleagues, Pupils, and Friends, ed. P. B. Grout. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1983. 86-98.

19. Saul Brody, "Reflections on Yvain's Inner Life." Romance Philology 54 (2000-01): 277-298.

20. Kibler, 350-351.

21. Kibler, 370-371.

22. Kibler, 373.

23. J.M. Sullivan, "The Lady Lunete: Literary Conventions of Counsel and the Criticism of Counsel in Chrétien's Yvain and Hartmann's Iwein." Neophilologus 85 (2001): 335-54.

24. Kibler, 315.

25. Ellen Germain, "Lunete, Women, and Power in Chretien's Yvain." Romance Quarterly 38 (1991): 15-25.

26. Kibler, 328.

27. Roger Boase, The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1977. 2-10.

28. Peter Nicholson, "The Adventures at Laudine's Castle in Chretien's Yvain." Allegorica 9 (1988): 195-219.

29. Please see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iwein.

30. Alois Wolf, "Hartmann von Aue and Chrétien de Troyes." A Companion to the Works of Hartmann von Aue. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2005. 67-69.

31. Ojars Kratins, The Dream of Chivalry: A Study of Chrétien de Troyes's Yvain and Hartmann von Aue's Iwein. Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1982. 118.

32. Thomas, 2935-2939.

33. Thomas, 2062-2072.

34. Thomas, 2115-16.

35. Thomas, 2310-2351.

36. Richard Phillips Abel and Bernard S. Bachrach, The Normans and Their Adversaries at War, Vol. 12. Woodridge, UK: Boydell and Brewer, 2001. 33-38.

37. Foster W. Blaisdell, Jr. and Marianne E. Kalinke, trans. Erex Saga and Ivens Saga: The Old Norse Versions of Chrétien de Troyes's Erec and Yvain. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1977. 32-33.

38. Blaisdell and Kalinke, 44-54.

39. Blaisdell and Kalinke, 44-54.

40. Carol J. Clover and John Lindow, Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Critical Guide. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005. 191-196.

41. Marianne E. Kalinke, "Characterization in 'Erex Saga' and 'Ivens Saga'." Modern Language Studies 5 (1975): 11-19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3194196

42. Yvain, lines 5410-5419.

43. J. Michael Stitt, rev. of Erex Saga and Ivens Saga, by Foster W. Blaisdell, Jr. and Marianne E. Kalinke. The Journal of American Folklore 92.366 (1979): 494-496.

44. G. Charles-Edwards, "The Scribes of the Red Book of Hergest." National Library of Wales Journal 21 (1989-1990): 246-56.

45. Sidney Lanier, "The Lady of the Fountain." Knightly Legends of Wales. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1908. 15-18.

46. Arthur C. L. Brown, "On the Independent Character of the Welsh Owain." Romanic Review 3 (1912): 143-173.

47. B.F. Roberts, "The Welsh Romance of the 'Lady of the Fountain,' Owein."The Legend of Arthur in the Middle Ages: Studies Presented to A.H. Diverres by Colleagues, Pupils, and Friends, ed. P. B. Grout. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1983. 178, 181-2.

48. Dr. Tony Hunt has commentary in Studia Celtica 8/9 (1973-74). On pg. 107-120 he mentions that though the tale is referred to as rhamantau (romance), the term is a bit misleading, and the term "tale" is more appropriate. In his opinion Owain is more like a folk tale rather than a romance.

49. R.L. Thomson, "Owain: Cheedl Iarlles Y Ffynnon." The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature. Eds. Rachel Bromwich, A.O.H. Jarman, and Brynley F. Roberts. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1995. 160-169.

50. Wendelin Foerster, ed., Kristian von Troyes Yvain. Halle: Verlag Von Max Niemeyer, 1902. xxvi.

51. Arthur C. L. Brown, "The Knight of the Lion." PMLA 20.4 (1905): 673-706. See also "Iwain in the Other World" and "The Other-World Landscape in the Romances and Lays," Iwain: A Study in the Origins of Arthurian Romance. New York: Haskell House Publishers, 1968. Reprint of work originally published in Harvard Studies and Notes in Philology and Literature 8 (1903): 1-149, accompanied by G. L. Kittredge's Arthur and Gorlagon.

52. Mary Flowers Braswell, "Ywain and Gawain: Introduction." Sir Perceval of Galles and Ywain and Gawain. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1995. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/ywnint.htm

53. Gayle K. Hamilton, "The Breaking of Troth in Ywain and Gawain." Medievalia 2 (1976): 111-135.

54. Joanne Findon, "The Other Story: Female Friendship in the Middle English Ywain and Gawain." Parergon 22 (2005): 77-94.

55. Ojars Kratins. "Love and Marriage in Three Versions of 'The Knight of the Lion'." Comparative Literature 16 (1964): 29-39.

56. Norman T. Harrington, "The Problem of the Lacunae in 'Ywain and Gawain'." The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 69 (1970): 659-665.

57. For an excellent scholastic edition of the Winchester manuscript edition of Malory, see The Works of Sir Thomas Malory, ed. Eugène Vinaver, rev. P. J. C. Field. 3rd ed., 3 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990. For a compact student edition, see Malory: Works, ed. Eugène Vinaver. 2nd. ed. Oxford University Press, 1971.

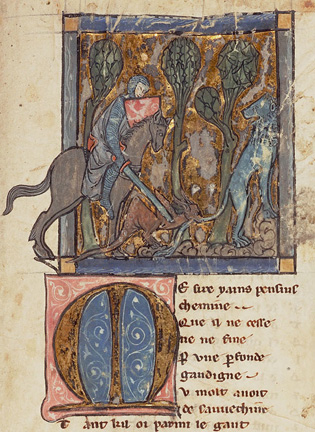

Yvain saving his iconic lion from the serpent.

The inspiration for Yvain is difficult to narrow down, as is the case with nearly all legendary figures. However, Yvain is unique among the Knights of the Round Table in that he is the only one who is based on a historical figure. He is recorded as some variation of Owain mab Urien, of the kingdom of Rheged. Of the historicity of this man there is little doubt. The earliest mention of Owain appears in the works of Taliesin, the bard of Urien, who composed a poem of lament in his honor. Already, elements of Owain (Yvain) as a fierce warrior can be found in the Lament For Owain ab Urien, who is remembered by Taliesin as someone who scattered his enemies like sheep.1

Taliesin’s poem is not the only source that records Owain. A few hundred years later, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae2 makes a reference to "Eventus the son of Urien"3 who was apparently one of Arthur’s companions. Furthermore, he is mentioned in Wace’s Roman de Brut4 as Ewein and is bequeathed Scotland, and appears in numerous Welsh works including the Mabinogion. While some appearances of Owain are radically different from what one would expect, such as his presentation as Arthur’s opponent in the Dream of Rhonabwy, by Chrétien’s time, aspects of his character, such as parentage, have already become tradition. It is unlikely, however, that the historical Yvain would have been a contemporary of King Arthur – the Owain of Taliesin’s “Lament for Owain” died c. 595.

It may be tempting to conclude that Yvain himself is an immigrant from the Celtic tradition. Two prominent medieval romances pertaining to Yvain, Owain: chwedl iarlles Y ffynnon (Owain: The Lady of the Fountain) and Chrétien’s Yvain, le chevalier au lion, seem to draw from a common source. Due to the great overlap between the two works, some scholars such as R.S. Loomis5 ardently propose that Chrétien must have drawn on Celtic sources to compose Yvain and he cites a number of prominent Irish tales as the work’s true origin.6 Others, such as R.L. Thomson,7 remain more cautious in their approach, pointing out that not only is it impossible to determine whether or not the Welsh Owain was the first version of this story, but also the precise nature of the relationship between Chrétien and his contemporaries cannot be determined with what scholars currently know. Chronologically, however, Yvain is found before Owain. Whether that implies one is dated before the other is another debate altogether.

However, it is possible to make some conclusions about the nature of Yvain. For one, it is almost impossible that Chrétien derived Yvain in isolation. At the same time, it is unreasonable to assume that he lifted the story piecemeal from the Celtic Tradition. What is more likely is that Chrétien knew of the Welsh tales and he may have found inspiration in them, taking some elements or names. In the process, however, he crafted something quite different from whatever its predecessor may have been. Fundamentally, Chrétien’s Yvain, like every derived Yvain afterwards, is a unique entity despite their superficial similarities. Given that Yvain acts as the foundation for numerous later works, it is only logical that it is looked at here first.

Chrétien

The exact date of composition of Chrétien’s Yvain is unknown, though almost all agree that it was composed sometimes in the latter part of the 12th century, and likely to have preceded his unfinished Percival. The text exists, more or less, in seven manuscripts, with the fragmented MS Garrett 125 from Princeton serving as a rare illuminated text of this particular tale.8It is a testament to Chrétien’s popularity that many of his works survive to today in their entirety. A master storyteller, he composed in verse,9 though most of his literary descendents will eventually retell them in prose. The appeal of Chrétien’s work, insofar as what the reader may be concerned with, lies primarily in the vision he presented. From his pen a fantastic realm appeared in the court of King Arthur, where the weak and innocent are protected by knights who dedicated themselves to the pursuit of chivalry and honor. It was a time when love was treasured, generosity was open-handed, and perfection attainable through exemplary actions.10 The knights of Arthur and Chrétien are very much paragons of virtue, regardless of what their true historical counterparts may have been.

Yvain, as such a knight, possesses the key trait of courtesy, which can best be summed up as a set of attitudes, behaviors, and traits pertaining to courtly behavior. Courtesy, in this case, is not only “proper” behavior, but it is used to describe chivalric behavior as a whole. The modern stereotype of the knight in shining armor rescuing princesses can be viewed as a shadow of this trope. However, when analyzing chivalric behavior, it is important to keep the dualistic aspect of its nature in mind. On one hand, an exemplary knight should be a mighty warrior. Indeed, adventures and deeds of valor seem to be the norm and are typically expected of an Arthurian hero. On the other hand, a knight must also be a courtly lover. The definition of courtly love varies, but in general,11 certain principles can be isolated. The lover is a vassal to the lady in love, no matter his rank or position. The lover must love the lady, and finally, should his love be requited, the lover must submit himself unconditionally to the guidance of his lady without a second thought.

Yvain’s courtesy is unmatched. The knight is humble, respectful, and noble. The reader is immediately introduced to this quality through the eyes of his cousin Calogarant and Queen Guinevere, who praises his courtly and prudent behavior. This is directly juxtaposed with Sir Kay, who could be viewed as the antithesis of courtesy. Kay is rude, quarrelsome, and thoughtless. He first slings a stream of insults at Calogarant, quipping that perhaps the knight wants to present himself as the best knight in court. Later, when Yvain comments on Calogarant’s defeat and offers to ride on his behalf to avenge his honor, Kay once again acts offensively, mocking Yvain’s suggestion and sarcastically asking the knight if the rest of the court should come as well. A lesser man may have retorted in kind – and rightly so, as Kay is obnoxious and his negativity is well-known. However, Yvain, showing him the proper courtesy, answers carefully:

Yvain’s courtesy is unmatched. The knight is humble, respectful, and noble. The reader is immediately introduced to this quality through the eyes of his cousin Calogarant and Queen Guinevere, who praises his courtly and prudent behavior. This is directly juxtaposed with Sir Kay, who could be viewed as the antithesis of courtesy. Kay is rude, quarrelsome, and thoughtless. He first slings a stream of insults at Calogarant, quipping that perhaps the knight wants to present himself as the best knight in court. Later, when Yvain comments on Calogarant’s defeat and offers to ride on his behalf to avenge his honor, Kay once again acts offensively, mocking Yvain’s suggestion and sarcastically asking the knight if the rest of the court should come as well. A lesser man may have retorted in kind – and rightly so, as Kay is obnoxious and his negativity is well-known. However, Yvain, showing him the proper courtesy, answers carefully:

"…Indeed, my lady, I don’t pay any heed to his insults. My lord Kay is so clever and able and worthy in all courts that he will never be deaf or dumb. He knows how to answer insults with wisdom and courtesy, and has never done otherwise. But I have no wish to quarrel or start something foolish; because it isn’t the man who delivers the first blow who starts the fight, but he who strikes back. A man who insults his friend would gladly quarrel with a stranger. I don’t want to behave like the mastiff who bristles and snarls when another dog shows its teeth…”12To the pleasure of the queen, Yvain’s response carries with it subtle meanings which showcase not only his courtesy but also his wit. He is unwilling to quarrel with Kay, as not only is Kay a fellow Knight of the Round Table, but Yvain prefers to avoid conflict by gaining the moral high ground through his inaction, thereby honoring the court in addition to himself. His tone is humble and modest, as is his speech throughout the romance. Unlike Kay, Yvain rarely boasts about his own strength or feats of arms. Instead, his prominence is announced through the words of others.

An important aspect of courtesy involves the proper treatment of women. In this regard, Yvain’s actions are legendary. With the exception of Laudine, whose ire serves as the central dramatic tension of the work, every woman who meets Yvain consistently praises him highly. Two occasions serve to highlight this characteristic. The first is his interaction with Lunete, and the second is the episode involving the Younger Sister.13

The audience is first introduced to Lunete when Yvain finds himself in mortal danger. Trapped behind the portcullis as a result of overly hasty action but heedless of personal safety, the knight wonders about the location of his opponent when an attractive damsel appears to him. She seems to be initially surprised by his presence, and points out that he is not welcome. While he has dealt the Fountain Knight a mortal blow, the rest of the castle will be searching for the slayer of their lord. Yvain’s response, characteristic of his humble self, is: "If it pleases God, they will never kill me, nor will I ever be captured by them."14 This humble relegation of his fate into the hands of the divine is reminiscent of other exemplary figures, such as Galahad, and is a trait displayed prominently in Chrétien’s Yvain.15

With his faith in the divine, Yvain possesses a confidence that makes him likable by the medieval audience. He is aware of his own abilities and though he believes that though God may intervene directly, in all of his battles he acts on this own, humbly serving only as a conduit for divine justice. Throughout the work, this humility remains consistent, which allows Yvain to act with supreme degrees of confidence – after all, when an omnipotent being is supporting his actions, it is difficult not to be confident.

The maiden, bantering on about his courage, quickly introduces herself as Lunete. Once again, Yvain’s nature as a courteous knight is highlighted. Lunete assists him out of gratitude and because he is a good, courteous person. When she visited Camelot on a prior trip, no one paid her any attention except for Yvain. The assistance she now offers him - both here and throughout the story - goes far beyond simple reciprocity. Her response, on one level, represents the divine providence that Yvain asked for, and she aids him in a number of ways. First, she brings him food and drinks to revitalize him; then she offers him sanctuary by giving him a magical ring that would shield him. On a symbolic level, the first gesture can be viewed as maintaining Yvain’s physical health, while the second is more abstract. In this case, the ring can be viewed as representing faith and courage, presented to Yvain because he is worthy of it. Faith is important in the ring’s operation because the user must trust in the maiden’s words – before he puts the ring on there is no direct evidence that the ring will work as she stated. Courage is necessary because while the wielder is invisible, he is not ethereal, and he needs to remain still to not give himself away. In either case, the ring remains an important detail that is retained in almost all of the works derived from Chrétien’s Yvain.

Courtesy not only saves Yvain’s life, but it is also representative of his way of life. When a problem is presented, Yvain instinctively dives into the situation because courtesy demands that he saves the lady, assists the lord in question, or slays the serpent. The association of courtesy with duty is strong in the latter part of the work, especially in the beginning of Yvain’s adventure as the Knight with the Lion. In fact, one of the first encounters for Yvain after regaining his sanity is that he comes across a lady imprisoned in a nearby chapel. Discovering that this woman has been wronged by her lady and is doomed to burn the next day, since she failed to obtain a champion within the allotted timeframe, Yvain inquires further in a courtly fashion. Interestingly, he offers to champion her prior to discovering her identity, which suggests that this gesture is initially out of courtesy. Regardless, once he discovers that the lady is Lunete, the matter goes beyond simple courtesy and becomes a personal issue instead. The responsibility for her plight now adds a second layer to the complexity of chivalric behavior.

Lunete explains that in his absence, Laudine felt betrayed by her, and Laudine’s seneschal, who is a dishonest man, accused Lunete of betraying her lady for Yvain’s sake. Of course, there was no such intention, but Lunete, flustered and confused, hastily responds that she would have herself defended by one against three to prove her innocence. The seneschal eagerly answers the challenge and gives her forty days to find a champion. Since that time, she visited numerous courts, but no one was able to take up the challenge. At the Round Table, Gawain is off rescuing the queen, and Yvain is nowhere to found.

After hearing this, Yvain is both touched and concerned for her. He is moved by both friendship and gratitude – indeed, the relationship between the two is remarkably close - and promises that he shall be there tomorrow. Lunete refuses at first, as she will not have both their deaths on her hands. What he is about to offer goes beyond courtesy in her opinion and she wishes to free Yvain from an unnecessary oath. The dialogue between the two is extraordinarily touching. For Yvain, regardless of the difficulty of the task, courtesy represents doing what is morally right. It matters very little what the odds actually are when God is on his side. While he acknowledges the dangers, Yvain is nonetheless confident that he shall prevail. Humbly placing his fate in the hands of God, Yvain declares that he shall win the day tomorrow, "if it pleases Him." With a mutual blessing, the two part, and the arc resolves itself soon after with Yvain winning the day handily, rescuing Lunete from the pyre in an extraordinarily dramatic fashion.

Another example of Yvain acting courteously is his encounter with the Younger Sister, which ultimately leads to a battle with Gawain. While in other works Gawain is portrayed as the epitome of chivalry; in Chrétien he makes an explicit blunder. Both the reader and the characters know that the Elder Sister's case is unjust. Gawain, however, thoughtlessly promises to aid her in whatever endeavor she chooses without deliberation or even an inquiry into the matter. This is in stark contrast to Yvain, who the readers have come to know as a careful and courteous individual. Though the situation resolves itself well, with Yvain earning honor and praise from the Sun of Chivalry, it is important to remember the circumstances in which Yvain receives the request. A series of divine portents, ranging from a cross appearing on the damsel's right to the sound of three horn blasts, guides her to Yvain, who promises that he shall do all he can to aid her. In a characteristic display of courtesy, he tells her that

"…No one gains a reputation by idleness, and I will not fail to act but will gladly follow you, my sweet friend, wherever you please. And if she on whose behalf you seek help has great need of me, don't despair. I will do everything in my power for her. Now may God grant me the courage and grace that will enable me, with His good help, to defend her rights….."16Courtesy, as stated above, is representative of the chivalric way of life. In essence, though Yvain is declared a traitor to his lady and subsequently "falls" from his rightful station as knight exemplar, the reader should bear in mind that Yvain's mistake—breaking his word to Laudine—though unintentional, is still his fault. His identity as the Knight with the Lion, then, is not a simple disguise. In order to win Laudine's heart back, he must prove himself worthy once again – indeed, that is exactly what he accomplishes at the end of the work, and this idea of self-redemption is cleanly woven into Yvain's character. The Knight with the Lion is an exemplary construct of courtliness – the reputation he possesses at the end of the story is built on a solid foundation of rightful deeds, three of which are given in the story itself. It is with this new reputation that Yvain is able to "repair" the damage done to himself.

Knightly prowess is also highly valued in Chrétien's world. This is not the most important trait, but inevitably all the best knights, such as Gawain and Yvain, are known for their martial abilities. For Yvain, however, his martial ability represents another side of courtesy, the desire for fame and glory, or, in his cousin Calogarant's word, "adventure." As the son of King Urien, Yvain is described as a prodome, or worthy knight. When Yvain first sets out to search for the fountain, adventure is on his mind, and the first instance in which his martial prowess is displayed is through the battle against the Knight of the Fountain. The battle is especially vicious, with neither yielding to the other. The Fountain Knight has previously vanquished hundreds of knights, and only Yvain is able to provide an adequate challenge. Finally, Yvain triumphs in battle and delivers a grievous head wound to the Fountain Knight, who flees from him and puts the rest of the story into motion as Yvain pursues him into his castle. While Yvain fights with passion and, at times, a lion-like ferocity, this ferocity is not to be mistaken for berserk rage. Yvain's motivation for chasing down the Fountain Knight is out of honor more than anything else. In order for Yvain to return to Camelot, he needs proof that he has visited the fountain or proof that he has defeated the Fountain Knight. Without evidence, Kay will simply mock him, which renders his trip irrelevant.

At this time, it is also appropriate to highlight Yvain's exceptional bravery. Trapped alone in enemy territory, he only feels a slight sense of discomfort. It is interesting to note that only in one instance does Yvain feel fear in battle, and that is against a pair of supernatural opponents. Given the symbolic meaning of his title, the Knight with the Lion, this fearlessness is appropriate. The lion is symbolic of many things, including bravery, nobility, and honor. In all of his adventures, even the ones involving the two demons, Yvain is spurred on by a sort of divine inspiration – he meets his challenges with unassuming confidence. If it be God's will (and it often is), then he is able to accomplish task X. This is most evident in the exchange of words in the Castle of Ill Adventures. Though the captive maiden warms him that he should not fight against the two devils, Yvain simply replies:

"May God, our true spiritual King, protect me, and restore you to honour and joy, if it be His will! Now I must go and see what welcome will be shown to me by those within."17After the episode with the Fountain Knight, Yvain encounters Kay in the defense of the fountain, as he has taken the role of its protector. In a nod to historicity, Chrétien shows that knights are not only errant-warriors and seekers of adventure, but they also carry within themselves important responsibilities such as defending their home and family. Of course, to everyone's satisfaction, Kay is effortlessly unhorsed and publically shamed – a karmic payback for his rudeness earlier.

The next battle which Yvain engages in is a curious one, for it involves two non-human combatants. A serpent (in some translations, dragon) is on one side, and a lion is on the other. For Yvain, the choice between the two is obvious. He fights the serpent because the serpent is "poisonous and foul," and because it was his "duty to combat evil." It is important to remember the circumstances of the encounter. Yvain has recently recovered from his madness, and is resolved to win his lady back through his deeds. Here, he helps the lion because the lion is a "courtly and noble" animal,18 and is a symbol of goodness. The text notes an inherent risk in aiding the lion because the lion may act unpredictably and could easily turn on its savior after the serpent is slain, and this serves to showcase Yvain's exceptional bravery in the circumstance.

Unsurprisingly, the lion, representing a godly creature, does not attack Yvain, but instead, acts in a very peculiar manner. It stood up upon its hind paws, bowed its head, joined its paws and extended them towards Yvain. Then, it "knelt down, and its face was wet with tears of humility." This gesture is representative of the ceremony of homage in which a vassal swears fealty to his lord, and from this point on the lion indeed acts as a vassal – bringing his "lord" meats from the wild and keeping watch over Yvain at night. More importantly, however, the lion acts as Yvain's second, serving as a mighty companion and often rescues him in spots of trouble. In fact, the lion aids him in all of his further adventures with the exception of his battle with Gawain.

Yvain is on a quest to regain his knighthood and to re-earn the love of his lady. It may be tempting to conclude that the lion is introduced as an agent of providence used to demonstrate the strength of God. This premise is tempting but incomplete; to do so diminishes the role of Yvain. Yvain's martial ability has not diminished in any way. Rather, his opponents have become increasingly more powerful, and the battles which he engages in are stacked against him. The lion becomes a necessary factor because its presence is needed to even the odds.19 The only battle in which he does not participate with his lion is the bout against Gawain, the greatest knight, and even then the two fight to a draw. In the other cases, against the two devils at the Castle of Ill Adventures, the seneschal and his brothers who wrongly accuse Lunete, and the giant Harpin, he fights against nearly impossible odds or supernatural opponents.

Harpin represents an enemy to the chivalric ideal. The giant spends nearly all of his time terrorizing the locals. Attempts at resistance have failed – Harpin has captured the ruler's six sons, slaying two of them in the process, and is blackmailing the lord by threatening to kill the rest if he did not receive the lord's daughter. When Yvain learns of the situation, he is obliged to root out this evil in accord to the chivalric code. Furthermore, he is the only knight capable of handling this matter, as his equal, Sir Gawain, is unavailable.

The process of battle reveals several interesting details. The first is that the giant behaves and fights differently from Yvain. Unlike Yvain, who possesses humility and grace, the giant is crude and uncountly. The episode, then, not only juxtaposes the two very different ideals, but serves to highlight Yvain's own martial prowess, as he initially gains the upper hand, and the giant is only able to temporarily resist him due to his tremendous supernatural strength before being vanquished.

In all of his battles, Yvain displays peerless skill in accordance with his reputation. Since most of these battles pertain to issues of morality, the lion participates and provides the knight with necessary support. The lion, acting as a representative of God's justice, enters battle to aid Yvain, and Yvain himself notes that "God and justice, who were on his side, would aid him, and that he relied on these companions and did not disdain his lion either."20

There is only one instance in which the lion does not participate in Yvain's combat, and that is in the battle against Gawain. Chrétien notes that the battle is one that would be unnecessary if the two combatants were aware of each other's identity. Yvain and Gawain are cousins, great friends, and companions. The text mentions explicitly that neither wishes to kill the other. Yet, paradoxically, the battle is unavoidable. The two knights champion different causes and now must give their all. The battle begins and continues for a long time, and both men are exhausted as they are evenly matched. When they pause, it is Yvain, "brave and courteous,"21 who speaks first and humbly acknowledges his opponent's skill. Interestingly, he does not yet yield – though, exhausted after hours of fighting, he says he is on the brink of defeat.

Gawain, just as exhausted, replies in kind – with courtesy in mind, he acknowledges Yvain's deeds as well, and comments that if there was anything that he had lent, Yvain has paid that back with interest. He is not as courteous as Yvain, however, and reveals his identity with pride.

"However it may be, since you would be pleased to hear the name by which I'm known, I shall not hide it from you: I am called Gawain, son of King Lot."22This is not to say that Gawain is a negative character. In fact, he is quite the opposite. Chrétien, however, uses the difference in dialogue to highlight the differences between the two exemplary figures, and uses this to separate Yvain from others who may also meet the criteria of a "good knight." Yvain's dramatic reaction and his declaration of yielding only serve to highlight his positive qualities. By the very act of yielding, one admits that his opponent is superior. Yielding to Gawain – the best knight – is not at all dishonorable, and Yvain is honored in turn as Gawain yields to him.

Arthur resolves the matter peacefully by taking matters into his own hands. He decrees that the Younger Sister shall have half of the inheritance. Under normal circumstances, it seems logical to appoint new champions to conclude the dispute, as trial by arms is often decided by divine guidance. In this case, however, the dilemma is not a moral one, and the knight gains more honor through this deed.

The Knight of the Lion, however, is ultimately a tale of reconciliation, and this brings up the final topic pertaining to Yvain's character. An exemplary knight is not only a force of good and a mighty warrior; he must also be a courtly lover. Hiding in Lunete's chamber, Yvain—along with the readers—is introduced to the female lead of the story. The knight is immediately smitten. Commenting that the lady has taken greater vengeance than she would realize, Yvain acknowledges his own feelings. Laudine, having wounded him through love by delivering a blow to his heart, is the physician to his problem. A sword blow can be cured or healed, but a wound caused by love only becomes more severe when it is nearest to its healing source. This emotion sets the rest of the tale in motion as it provides motivation for Yvain's actions.

Love is illogical. As Yvain observes Laudine's grief, he comments on its nature, and praises her beauty. This praise is not necessarily shallow, though it may appear to be to a modern audience. Yvain praises her physical qualities – she is nature's marvel, and like a proper courtly lover, he is madly in love with her. When Lunete returns, she offers to take him out of the castle. Yvain, as expected, refuses to be removed. However, he says only that he refuses to leave secretly like a thief, but he doesn't speak of his love for Laudine.

Lunete, being no fool herself, instantly guesses his desire. She immediately goes to Laudine, and begins to work on Yvain's behalf.23 She argues for him on several grounds: logical, as Laudine will need a new husband to defend her fountain; ontological, as it is almost certain that God will send her a better man; emotional, as she wants a man in her life. Laudine's response, upon first glance, seems too emotional: she merely says doesn't want to. Acridly pointing out that Laudine had in her the "same folly that other women have,"24 Chrétien notes that all of them refuse to accept their own desires. Laudine is by no means oblivious or stupid. She is aware of the concrete threat to her domain, but she is unwilling to address it at the moment for two very acceptable reasons. After all, Yvain has just killed her husband, and it would be unusual if she just decides to marry him now. Furthermore, she does not know Yvain at all, and though she is aware of his reputation, she questions his motivations for wishing to marry her. This questioning sets off a chain reaction in her mind in which she eventually concludes that she may be able to accept him after all. Here, the presented idea in relation to the courtly lover is that women have their moments, and that though they may act in "folly," the proper behavior for the lover is to carry out their desires to the best of his ability. In this case, Yvain has been (impatiently) waiting for an audience over the last week, in accordance with correct behavior.

Lunete, being no fool herself, instantly guesses his desire. She immediately goes to Laudine, and begins to work on Yvain's behalf.23 She argues for him on several grounds: logical, as Laudine will need a new husband to defend her fountain; ontological, as it is almost certain that God will send her a better man; emotional, as she wants a man in her life. Laudine's response, upon first glance, seems too emotional: she merely says doesn't want to. Acridly pointing out that Laudine had in her the "same folly that other women have,"24 Chrétien notes that all of them refuse to accept their own desires. Laudine is by no means oblivious or stupid. She is aware of the concrete threat to her domain, but she is unwilling to address it at the moment for two very acceptable reasons. After all, Yvain has just killed her husband, and it would be unusual if she just decides to marry him now. Furthermore, she does not know Yvain at all, and though she is aware of his reputation, she questions his motivations for wishing to marry her. This questioning sets off a chain reaction in her mind in which she eventually concludes that she may be able to accept him after all. Here, the presented idea in relation to the courtly lover is that women have their moments, and that though they may act in "folly," the proper behavior for the lover is to carry out their desires to the best of his ability. In this case, Yvain has been (impatiently) waiting for an audience over the last week, in accordance with correct behavior.The two characters – lady and maidservant – are often juxtaposed. Lunete generally operates in a far more logical and level-headed fashion than her mistress,25 though her hotheadedness is what lands her in trouble in the latter half of the tale. Her intelligence complements Laudine and Yvain, and is instrumental in the two's initial meeting, as well as their reconciliation. Laudine, on the other hand, can often see the reasoning behind events despite her emotional tendencies. The interaction of Yvain with these two women reveals two notable traits of the knight. With Laudine, he is the perfect lover – theoretically obedient to the point of thoughtlessness, and genuinely wishing to place her interests before his. With Lunete, he is more at ease, able to self-reflect and both give and receive counsel when it is needed.

Prior to meeting Laudine, Yvain is depicted as the perfect knight. After meeting Laudine, his status as a perfect knight has not changed – he is still Yvain. Nonetheless, there must be a balance in the knight between the adventurer and the lover. When Gawain comes to take Yvain to seek adventure, he offers two very persuasive reasons for him to come along. The first is that the husband who honors himself also honors his wife, and the second is that his love for the lady grows stronger if they are apart. Even so, it takes a week for Gawain to tempt him towards adventure, and he first goes to request permission to leave from his lady, as it is proper for him to do. Yvain is cautious because it is in his character, and it shows his reluctance to carry out a task with the slightest potential to hurt Laudine.

Laudine, as is characteristic of her, unhesitantly grants him his request without inquiring into the matter. When the knight says that he is leaving, however, her mood changes immediately. The limit she set for him is arbitrary – it shall be a day of her choosing, and should he overstay, her love for him will turn to hatred. Upset, Yvain notes that her conditions are too strict, citing possibilities of imprisonment or injury. This shows his care in attempting to ensure that he can carry out her will. To solve the problem, Laudine hands him a magic ring. The ring's property addresses his concerns by preventing physical harm, illness, and imprisonment, all the conditions that would prevent Yvain's return to her. Here, this ring represents her love as well as her trust, and Laudine makes it clear to him that the true matter here is that of his fidelity as a lover, and should he prove himself to be false, then she will reject him. Ironically, when she demands it back in a later episode, the ring actually proves Yvain to be a true lover, since he wins every tournament he participates in, and suffers no injuries.

Chrétien, however, offers no elaboration for Yvain's overstaying, except for an observation that Gawain would not allow him to leave his [Gawain's] company. To illustrate that Yvain is loyal and is, in fact, miserable without his lady, Chrétien describes him as a body without the heart: "The king might take his body with him but there was no way he could have the heart, because it clung so tightly to the heart of her who remained behind that he had no power to take it with him. Once the body is without the heart, it cannot possibly stay alive, and no man had ever before seen a body live on without its heart. Yet now this miracle happened, for Yvain remained alive without his heart, which used to be in his body but which refused to accompany it now. The heart was well-kept, and the body lived in hope of rejoining the heart; thus it made for itself a strange sort of heart from Hope, which often plays the traitor and breaks his oath. Yet I don't think the hour will ever come when Hope will betray him; and if he stays a single day beyond the period agreed upon, he will be hard pressed ever again to make a truce or peace with his lady."26 The metaphor of body sans heart is particularly interesting, because in the accusation that follows, the unknown damsel contends that Yvain has stolen her lady's heart. Though his love for her is explicitly detailed in his inner reflection, he nonetheless breaks his word, and the knight becomes distressed as he reflects upon it. This marks a critical shift in the story. Previously, Yvain is portrayed as an exemplary lover. Here, however, he accidentally breaks one of the most fundamental rules in verais amors 27 - being a vassal in his love's service. He should have returned at the appropriate time – and indeed, he had all intention of doing so. But because of his failure, the ring – presented as a representation of Laudine's love for him – is taken from him. Throughout her speech to him, the damsel addresses Yvain with tu, an informal (and in this case, disrespectful) form rather than vous. Laudine lacks the knowledge – or perhaps, simply chooses to ignore evidence that proves Yvain innocent, and rightfully accuses him of being a traitor. Yvain has failed in two ways. He broke his contract with his lady and his promise as a lover by overstaying. He is now no longer trustworthy, and trust must be restored. Unsurprisingly, the knight falls into a bout of momentary madness. This madness serves as a transition point, allowing Yvain to lose all aspects of his humanity in order to construct himself anew. The new identity and name he makes for himself as the Knight with the Lion is reflective of such a change, eventually serving to bring him back into the graces of Laudine.

Before the ultimate reconciliation, Yvain meets Laudine under the disguise of the Knight of the Lion. His response to her is extremely prudent and appropriate, as through his self-blame he frees Laudine from the charge of discourtesy she had inadvertently aimed at herself. Yvain is acutely aware of what is necessary for him to do to regain her favor, which is making a name for himself. He does not reveal his true name, because neither he nor Laudine is ready. He has dishonored himself in the eyes of his lady. This is a point on which Lunete will capitalize later, as she once again lures Laudine into promising that she will do all she can to assist the Knight with the Lion in regaining her lady's favor, a promise which foreshadows the events to come.

At the end, when Yvain goes to be reconciled to his lady, many events mirror their first meeting. The storm occurs, a motif that represents Laudine's state of mind. Lunete also speaks first, which begins the reconciliation process. Laudine initially appears to be indignant at the fact that she has been tricked into reconciliation, though later she nonetheless decides to forgive him for his transgressions. Here, Chrétien emphasizes the emotional quality of Laudine's responses. Laudine speaks dramatically, using a number of conditionals in her dialogue. She is upset not at Yvain but at the fact that she cannot take back an oath that has been made. The whole ending may feel somewhat less than satisfactory. Yvain, however, is content. As a courtly lover, Yvain has painstakingly redeemed himself through his actions, and as the Knight with the Lion, he has accomplished much to honor her. Laudine is aware of this, and in context, her complaints may simply act as a veil, rather than concrete reasoning. She does not have to take him back – but after all he has done, and since he is genuinely sorry, there is no reason for her not to forgive him.

This reconciliation is also not a simple restoration of the status quo, but rather an advancement. The reconciliation between Laudine and Yvain brings together two different values – love and chivalry. Le Chevalier Au Lion can be viewed as a thematically coherent work. The two traditions of love and martial prowess are combined through a set of common values encoded in chivalry itself, and by the end, Yvain is able to adhere to both. His actions are out of courtesy and honor, and the theme of reconciliation is consistently present throughout the tale.

The story, then, is not about Yvain becoming the perfect lover or the perfect knight as much as it is about his adapting of a perfect balance between the two by becoming the Knight with the Lion.28 In a sense, he receives no special training to improve his martial abilities, nor does he suddenly realize some hidden art to allow his beloved to love him again. Yvain's character, strangely static in nature, evolves through the synchronization of the two values. If Laudine's rejection can be viewed as the midpoint in the story, then in the first half, he is already the perfect fighter – winning over Laudine's heart after completing an appropriate adventure by defeating the Fountain Knight. As a lover, though he makes an unintentional mistake, through the construction of a new identity as the Knight with the Lion in the second half, Yvain redeems himself in Laudine's eyes. As the Knight with the Lion, he earns praises from both Gawain, representative of chivalric ideals and Lunete, representative of courtliness and the lover. Gawain allows him to reach the pinnacle of knighthood by becoming equal with the best, and Lunete helps him to reconcile with the lady he loves. Ultimately, the tale concludes with Yvain becoming an ideal knight through the balance of love and chivalry.

While each Yvain possesses universally idealized virtues such as courage and honor, later works about him emphasize different qualities and subsequently interpret Yvain through their own cultural understanding. It is perhaps this malleability in his characterization that makes Yvain popular, because it is not long before he enters the stories told in countries surrounding France, each with its own twist.

Hartmann von Aue

Composed around 1203,29 Hartmann von Aue's Iwein is a Germanic romance based on Chrétien's Yvain, but it can be thought of as an alternative interpretation of Chrétien's text. Whereas Yvain concerns itself with reconciliation of two lofty ideals, Hartmann seems to be more concerned with the mundane. In particular, the relationship between Iwein and Laudine is presented differently, and the central conflict between the two is one of both responsibility and romantic love. Hartmann stresses the importance of love in a lasting relationship by emphasizing honor and oaths in his work, and the question of attaining happiness in a stable relationship is a central theme to Iwein.30Before the question of responsibility or love can be addressed, it is important to note that the protagonist, Iwein, is very different from his French counterpart. The first distinguishable difference, though subtle, is that his glorification is attributed more to himself than to God. In the first adventure inside the Fountain Court, Chrétien's Yvain places his life in the hands of God. However, Hartmann's Iwein, responds that "then at any rate I shall not lose my life like a woman. No one shall find me without defense." Here, the emphasis is on Iwein's own actions, and Lunete has to remind him that life is ultimately in the hands of the divine.

That is not to say that the divine is removed from Hartmann's work. A detail which Hartmann created explicitly for Iwein, the acquisition of a bow and arrows from a boy during his bout of madness is an act of divine providence. However, the work as a whole is still more secular in nature. The lion, for instance, is substantially less important than it is in Yvain. Hartmann omits two important details. The scene of homage is removed completely, and he neglects to note Yvain cutting off a piece of the lion's tail in the rescuing process. All of this points to a different focus in Hartmann's work. Whereas in Chrétien, the lion is an agent of God, here, the lion is only one aspect of Iwein's chivalric prowess. In a roundabout manner, the presence of the lion is a result of his chivalric reawakening, rather than a tool and companion provided by providence to achieve his goal. In a sense, the lion is part of a spiritual reawakening that is complete after Iwein wakes from his madness.

While the focus of Iwein is more secular, the knight nonetheless integrates faith into his actions. The singularly most important departure from Chrétien is Iwein's "awakening," beginning on lines 3515-3528. Generally, Iwein introspects less than Yvain, but in a rare instance of self-reflection he recovers from his madness and comments that:

"Alas, what honors I enjoyed while I slept! I dreamt of great worthiness. I had noble birth and youth. I was handsome and lordly, quite unlike my present appearance. I was courtly and intelligent and had won much hard-earned renown at chivalry. If my dream did not lie, whatever I wished I conquered with sword and spear. With my own hand I won a wife and a noble domain."The explicit reference to Iwein's personal qualities and attributes links the present to the past and allows Iwein to experience a reawakening. Previously, his attitude towards secular life was highlighted, as things such as honor, glory, wealth, and power are all prizes of a worldly existence, rightfully given to one who should be honored. This attitude, however, ignores a common value at the time: that God is the root of all achievements. The recognition of all of this loss can be viewed as a positive thing because it allows Iwein to focus on what has been lost, and the proper way of regaining the worldly prizes.31 By adhering to the values of minne (love), êre (reputation), and rehte güete (true goodness), Iwein becomes a model for chivalric behavior. He is now aware of what he should do, and now he begins to do it. Hartmann shows this by telling the readers that the moment he puts on knightly dress, Iwein suddenly regains his memories, and simply resumes his role as the exemplary knight with nary a second thought. Indeed, by the end of the tale, armed with the right beliefs, Iwein regains all that he has initially lost, including his domain and his lady.

As an exemplary knight, Iwein has no equal. The Germanic work has a stronger focus on the concept of chivalric honor than on courtly love, though love is by no means neglected in the tale. The issue of honor and shame is brought up throughout the work and provides a framework for many of the episodes in the story. Kalograent challenges the Fountain Knight because it would be shameful and cowardly for him to do otherwise. Iwein's initial motivation to seek the fountain is also prompted by shame because otherwise Keu will dishonor him. However, the best example comes from Lunete's message to Iwein when he overstays, as her accusation of Iwein carries two major points, both of which pertain to shame. Iwein has shamed Laudine by causing her emotional trauma through the killing of her husband. Furthermore, because Iwein is incapable of keeping his word, he dishonors his knighthood and his wife through his irresponsibility.

This idea of irresponsibility is a departure from Hartmann's predecessor. In Chrétien, Yvain's fault is a problem of love. By not returning to Laudine, he is being an unfaithful lover, and his subsequent descent into insanity is caused by this loss of love. Hartmann's Iwein, however, is blameworthy because of his irresponsibility. As a knight, he is obliged to defend his lady and domain but fails through his inaction. Thus, Iwein's madness is caused by a multitude of emotions stemming from Lunete's accusation. He is affected by shame, dishonor, sorrow, regret, and the loss of his lady's love.

While courtly love exists in the Germanic tradition, its role has diminished significantly in Iwein. Iwein does not deliberate for a week before asking Laudine his question, nor is there any mention of the lover's heart in their dialogue. Gawein's argument is simple. Though Iwein has won, through his own hands, a domain and a wife, he should still go out and act in a knightly way. The reasoning here is the reverse of Chrétien's. Iwein seeks adventure because it is his knightly duty to accomplish deeds, and through his accomplishments he shows love for his lady.

Iwein's character, however, would be much diminished were it not for the unique presentation of his lady, Laudine. The interaction with Laudine has a different tone. Laudine simply comments that should he not return in time, he would be risking all of their honor, as well as their domain because the fountain would not have a defender.32 The main obligation presented here for Iwein is his duty as her husband and not fulfillment of his role as a courtly lover found in the French work. Laudine's request is reasonable from all perspectives. The ring presented to Iwein loses its nature as an artifact showcasing the power of love and instead acts as a simple reminder. It is not a conditional item that requires unswerving devotion, and the relationship between Iwein and Laudine appears much more balanced than that found in Chrétien.

In every sense, the two – knight and lady – are presented as equals. This is evident from the beginning of their interaction. When Iwein sees Laudine, he feels the same way as his French counterpart. In both cases, it is love at first sight. However, he is not at all anxious to pursue her romantically. Rather than immediately falling into the mode of a courtly lover, he introspects and realizes that the solution to his dilemma now lies with Laudine. Though he is the initiator of the relationship (by killing her husband, no less!) he is now obliged to wait on her response. She may reject him out of anger, but there is very little he can do except to wait – an attitude that is quite different from Chrétien's Yvain, who refuses to leave until his heart's desires could be fulfilled.

The relationship in Hartmann's Iwein suggests a subtle difference in the attitude towards love from its predecessor. On the most basic level, Iwein is obliged to stay with Laudine should she choose to accept him - he has slain her husband and left the fountain without a protector. Laudine, in contrast to her prototype, is significantly more reasonable, and Hartmann shortens all of her other internal monologues except for the one containing the idea that perhaps Iwein does not deserve her ire. While her initial response is out of genuine despair, she comes to realize that Iwein acted in self defense, and had he done anything otherwise, he would be dead. This understanding and the following monologue seem to reflect something that is unique to Hartmann.

"In God's name, I shall cease being angry, and if it is possible, wish for that very man who slew my lord… Then he will have to make up with devotion for my grief and hold me the dearer because he has caused me pain."33

The reflection is present in Yvain, but there, Laudine dismisses it abruptly and does not consider it. In Hartmann, this idea of responsibility is consistently present, and the growth of her affection for Yvain is more and more evident. The love presented between the two is almost egalitarian. Courtly love is there, but in a much diminished form, and nowhere does Laudine display the same level of authority that is found in Chrétien's Yvain. In fact, there is a demure side to her that occasionally surfaces in Hartmann's work. For example, after she has learned of Iwein's true identity, she asks an important question that would be unthinkable from the perspective of Chrétien's courtly lover: "But, my friend, do you actually know that he wants me?"34 This maidenly query is a radical departure from her predecessor and highlights Hartmann's intricate work. As it turns out, Iwein and Laudine not only love and accept each other as husband and wife, but there is a mutual obligation to each other. However, passion is not lost in Hartmann's work either. Whereas Chrétien's Yvain promises his lady his love with great flair, Iwein exalts Laudine with simple words that are nonetheless rooted in courtly love. "I do not know how to offer you more honor than this, but you should sentence me yourself. Your pleasure is mine."35

The similarity between Iwein and Yvain hides very different attitudes, and the dialogue exchanged by the lovers highlights several important values. The artistic liberty exercised by Hartmann seems to suggest that responsibility is key to a stable, loving relationship. The promise Iwein makes is a promise to her as a person – which renders his accidental betrayal all the more significant when it eventually happens. Laudine's tone and words are not authoritative and she lacks the extreme willfulness found in her predecessor; thus she is placed on the same level as Iwein. Their exchange is not only one that is fundamentally between equals but possibly one of the most appealing exchanges in medieval romances, carrying within it all the eloquence and charm of the work while lacking nothing in realism.

Thus, because the idea of responsibility is so highly valued, it is no wonder that Iwein's misconduct, no matter how unintentional, is significant. The conclusion of Hartmann's work is a return to the status quo in the sense that it is a return to honorable and responsible conduct. Hartmann takes great liberties in his conclusion, working in a much more satisfying ending especially to the modern reader. While the events still remain superficially the same, there are differences. As the Knight with the Lion, Iwein's honor has been regained earlier through his knightly deeds, plateauing at the point where he fights Gawein to a draw. The reconciliation is anticlimactic, as Lunete "lures" Laudine into promising to assist the Knight with the Lion because he is a very steadfast person. In this sense, the original cause of Iwein's fall from grace – his breaking of his word – is already repaired. Consequently, their reconciliation is reminiscent of their initial meeting, with Laudine once again portrayed in a far more flattering way than her counterpart in Yvain. There is a certain endearing sort of awkwardness in the way she first poses her questions, and though she protests that Lunete has trapped her in an oath, this protest is far less severe than the one found in Chrétien. Hartmann is only nominally keeping to the source material as Laudine goes on to assert that love is not simply dutiful worship on her knight's part, but rather a matter of mutual obligation. After Iwein has apologized, she apologizes in turn – acknowledging his suffering and falling on her knees to ask for his forgiveness. In essence, Hartmann took what remained of the capricious beauty from the otherworld that might have influenced Chrétien and distilled her into a noble young woman, regal in every way and perhaps paradoxically, humble and acutely human.

The reconciliation scene is vital for a number of reasons. First, it shows that forgiveness is a matter that goes both ways. Secondly, it shows a very different relationship between the lovers than in Hartmann's source material. The lovers here are equals, bound to each other by a pledge of duty to each other not unlike the oath of marriage. While kneeling and asking for forgiveness is incongruous with the courtly beloved of Chrétien, the very act of asking for forgiveness implies Laudine is the perfect wife. In Hartmann, this willing submission between the two provides a touching and dignified ending to the story.

Ivens Saga

In the Scandinavian tradition, Yvain appears in Ivens Saga, one of the riddarasögur, which loosely translates to "tales of chivalry." It is presented as a prose narrative unlike the other Yvain romances, and is preserved in three manuscripts – Stockholm 6, AM 489, and Stockholm 46 – though only Stockholm 46 contains the complete tale.36 The language feels terse and occasionally impersonal, lacking the rhyme and flavor of English, French, and German versions. Some scholars have called these works "abridged,"37 and rightly or wrongly, the feel is different. The idea of courtliness, a central theme in Chrétien, is alien to the Scandinavian culture, and characters are altered accordingly to better suit the audience. Love is also strangely absent. If Yvain is the exemplary knight, then Iven can only be described as the exemplary warrior.Honor is the foremost matter, and inevitably, every idea and reason presented in the saga relates back to honor in some way. The focus is on the gain, loss, and regaining of honor, and less on courtly love. In Chrétien, during the initial encounter between Laudine and Yvain, Laudine queries his reasoning for submitting himself to her. Yvain states that he is:

"… not afraid of doing anything that may please you to command of me, and if I could make amends for the slaughter, in which I did no wrong, then I would make it good without question."38Here, Yvain's meaning is clear. In Chrétien, he holds no responsibility for the slaying of the Fountain Knight. The act is done out of self-defense, and rightly or wrongly he is still alive at the present moment thanks to divine providence. Iven, however, addresses her differently.

"I shall gladly do everything that is pleasing to you, and I am not afraid, even if the greatest danger is involved. If I might compensate for the death of the one I killed – I did not transgress against him – then I would do that so well that no one might find fault with it."39Superficially, the response is similar. The author of Ivens Saga, however, inserts the idea of compensation. In the saga, Iven is responsible to both Laudine and the now-dead Knight of the Fountain. Unlike Yvain, who claims innocence, Iven is explicitly aware of the consequences of his actions. The matter of honor is highlighted, though the rest of the dialogue carries on in the same way.

Honor is everywhere. Gawain lures Iven away from home because if he stays home, he will ruin his knightly reputation and accomplishments. When Iven goes to his lady to request permission, the Norse translator kept the issue of cowardice but ignored almost all of the rest. There is no discourse about love or the nature of the lover in Ivens Saga, and Yvain's agonizing monologues are strangely absent. Laudine speaks of love in Chrétien, threatening Yvain with the loss of her love should he not return. Laudine in the saga, however, stresses the breaking of vows. Love seems to be irrelevant – what matters, however, is the oath to her as a person. The threat to Iven is not the loss of love, but rather the loss of his honor. The ring, a token of the true lover in Chrétien, is just an ordinary. Accordingly, when Iven overstayed, the important matter is that he is treacherous. The idea that he is a deceitful lover is glossed over and is not given the same level of attention found in Chrétien.

Honor, again, is paramount, and though it changes the tone and implication of the final reconciliation, the story remains fundamentally the same. In the end of Chrétien's romance, Yvain reconciles both chivalry and love and returns to his position as the exemplary knight. In the saga, however, Iven simply regains his honor, and everything else, including love, seems to fall into place. The translator, removing a great deal of Yvain's flowery praises and speech, shortens the work considerably and makes the story of Iven into one that is chiefly action-driven. Certain sequences are liberally edited to add drama to the story. For example, when Iven first enters the Fountain Court, he is actually seized by the fallen knight's retainers and imprisoned. In other episodes, the author makes conscious changes to the tale that reflect his own interpretation of the tale.40

True to his cultural roots, Iven answers almost all matters of inquiry in a curt, laconic way. This curtness is only one aspect of the Norse Iven that emerges altered from the French tale. Iven, for example, does not fawn over his lady in speech. He is not rude, but he does not heap praises upon her as Yvain would, nor is he eager to heap blame upon himself in an attempt to regain his lady's approval. In his first encounter as the Knight with the Lion with Laudine, he makes no active effort to name himself as the party-in-the-wrong and simply answers all of her questions before leaving. Perhaps due to the lack of courtly veneration, the women that Yvain interacts with are presented as more independent. That is, they feel more like persons to the reader rather than things to be cherished and worshipped. Scholars such as Kalinke41 argue that this is because women are more liberated in Scandinavian society. She cites an excellent example in the episode in which Yvain battles the two demons. In the saga, the lord of the castle promises Iven his daughter should he be victorious. Iven's response is curt, expressing surprise and disgust at the idea of bargaining for someone. To him, she should always live free. Compare this to Chrétien's Yvain, whose response is:

"…May God grant me no share here, and may your daughter remain with you. In her the Emperor of Germany would find a good match, were he to win her, for she is beautiful and well-bred."42Kalinke contends that this shows the idea that woman is equal to man. The men of Ivens Saga respect her by refusing to consider her as an object, which offers readers a further glimpse into the world of the Norse. All of the evidence found in the surviving Ivens Saga, however, seems to suggest that it is, for lack of a better term, manly, highlighting action and paying little attention to anything else. Iven, however, is not so much a caricature of manliness as a warrior, with his foremost concern being honor and the oaths that he has made. With this point in mind, what some critics perceive as literary shortcomings of Ivens Saga43 can instead be viewed as adaptations of Chrétien that are suitable for its targeted audience: the proud Scandinavians living far removed from the French high courts.

Owain: The Lady of the Fountain

The text of Owain is preserved in several medieval manuscripts, all of which appear to have been written after Chrétien's work. The only complete version of the prose tale is found in the Red Book of Hergest, which was written after 138244 (though the tale itself was probably written in the thirteenth century). The story shares many elements with Yvain and has the same fundamental structure. The hero, Owain, engages in a preliminary adventure that ends in his winning the hand of his beloved in marriage, then through some fault of his own, he falls from grace and eventually reconciles with his wife.

The text of Owain is preserved in several medieval manuscripts, all of which appear to have been written after Chrétien's work. The only complete version of the prose tale is found in the Red Book of Hergest, which was written after 138244 (though the tale itself was probably written in the thirteenth century). The story shares many elements with Yvain and has the same fundamental structure. The hero, Owain, engages in a preliminary adventure that ends in his winning the hand of his beloved in marriage, then through some fault of his own, he falls from grace and eventually reconciles with his wife.Overall, Owain is best described as an alteration of Chrétien's masterpiece. Apart from the fact that it is shorter, there are distinct differences between Owain and Yvain. Examples include the de-emphasis of reconciliation - the reconciliation of Owain with his lady is mentioned in one line only. There is no issue to be resolved with the sisters at the end, and thus Owain battles Gwalchmai (Gawain) at a totally different point in the tale. The lion plays an unclear role, as it is not a direct representation of divine favor, nor does it act as a guide to the otherworld, which would be appropriate for an animal companion appearing in a Celtic tale. The episode involving the Castle of Ill Adventures has been shifted to the end (for reasons discussed below). The text appears to be truncated, with each account of Owain's adventure growing progressively shorter towards the end of the story.

Evidence suggesting that the Welsh text is derived from Chrétien comes from several events that are presented illogically and that only make sense in context of Chrétien's work. One such example is the episode concerning Owain's shame. In Chrétien, a ring that is representative of Laudine's love is introduced and subsequently taken away. In Owain, however, the ring is taken from Owain, but there is no mention of him ever receiving a ring except for the one from Luned (Lunete). Another instance of Owain's disjointed nature is in Owain's first meeting with Luned, who, upon the meeting of a complete stranger, said:

"Truly, it is very sad that thou canst not be released, and every woman ought to succor thee, for I never saw one more faithful in the service of ladies than thou. As a friend thou art the most sincere, and as a lover the most devoted. Therefore, whatever is in my power to do for thy release, I will do it."45In Yvain, a motive for Lunete's actions is that Yvain has treated her with courtesy and respect, and she now repays him for his kindness by offering to aid him. Luned's response in the Welsh text, however, makes little sense unless the readers know her response from Chrétien – the notion of saying such a thing to a complete stranger is nothing short of absurd. Scholars such as Arthur C. Brown46 suggest that the Welsh author may have had a "lost leaf," if he was working from Chrétien's story, but this in itself does not explain numerous continuity errors, such as the one mentioned above, that litter the piece as a whole. If the composer of Owain is merely trying to copy Chrétien, then he must have been rather careless in his approach.

Nonetheless, Owain is a unique literary work, and Professor Brynley Roberts47 notes that the piece is enjoyable, distinct, and valuable no matter its relationship to Yvain. There are numerous elements that are distinctively Welsh inserted (or perhaps reclarified) in the tale. It is more plot-driven than character-driven and reads more like an epic than a romance.48 Owain himself shares many traits that are more Welsh than French or English. In Chrétien, Yvain's reputation is established through his deeds – most of the characters, such as Lunete, know or know of him from his courteous actions at court and his abilities as a warrior. Owain, however, possesses a sort of magical charisma similar to Diarmaid that is left unexplained in the story. Whereas Chrétien, Hartmann, and other authors highlight various qualities, Owain's abilities as a leader seem to be most prominent and are constantly brought up in the story. The focus on kingship is a chief difference that may help to explain why, if Owain is indeed derived from Chrétien, the author decided to shift the narrative structure by placing certain adventures at the end of the tale. The final episode in the Castle of Ill-Adventure represents Owain's final adventure before settling down permanently to his responsibilities as a king, and would be an appropriate place to end the tale.49

In terms of uniqueness, there are a number of constructs that are exclusively Welsh in nature, and supporters of the notion of Owain as an independent work or the source to Chrétien's Yvain cite these points as evidence to support their argument. These critics, such as Kittredge, Foerster50, and Brown51 note subtle differences, such as references to mounds in the meadow or to a fay steed as evidence that Yvain is fundamentally a story about a journey to the otherworld. From this perspective, then, the strongest evidence comes from the presentation of the fountain itself. In Owain, the shower generates great hailstones that strip trees bare, which is a very common motif in Celtic and Welsh legends – an elfin storm from fairyland that adventurers to the other world often face as an obstacle. This element is absent in Chrétien due to either artistic liberty or carelessness, and the simpler explanation is that Chrétien did not understand the reference wholly. Another example is Owain's association with ravens, which is an indigenous element from Welsh culture.

The most logical conclusion would seem to be that both Owain and Yvain draw upon some common source, but the question of influence shall forever remain inconclusive. Brown and others would contend that the story, in its purest form, originates from the archetypal hero on a journey to the other world. Laudine's origins lie in the fairy lover, and Chrétien added the Castle of Ill-Adventure and the Quarreling Sisters independently. Still others, such as Thomson and myself, would argue that a middle ground is best when it comes to interpreting Yvain. Even if Chrétien did have Welsh sources on hand, Yvain is far too different from its source material to be anything other than a high romance. Owain, on the other hand, might be what a French romance would look like in the Welsh tradition, and perhaps it is a glimpse of what the roots of Yvain may have been.

Ywain and Gawain

The dating of Ywain and Gawain is problematic, but most consider it a product of the 14th century. Considered by many to be a direct translation of Yvain, the text is streamlined and reduced to not even two-thirds the length of its predecessor.52 Like Hartmann's Iwein, Ywain is a distinct departure from Chrétien. It is a work that concerns itself with many more social and moral elements, and the poet seems to be greatly concerned with what is considered to be appropriate behavior for a leader. The one word summation of the ideals presented in Ywain is the concept of trowth, a term used to idealize the concept of trust and faith in all interpersonal relationships.53 Thus, before there can be love, there must first be oath-making and promises. Everything else becomes a matter of fulfilling such oaths in a practical manner.54For example, in the marriage between Ywain and Alundyne, there is little affection on Alundyne's part. An ardent declaration of love in Yvain and a heartfelt exchange of vows in Iwein becomes a business transaction in Ywain, with Alundyne explicitly commenting that she needs a protector, and she marries Ywain out of concern for the safety for her lands. The idea of obligation, in contrast to its presentation in Hartmann's Iwein, is far less personal. Whereas Hartmann's Iwein is personally invested in the marriage, Ywain's actions seem to presented on the grounds of cost and benefit – again, gaining land. When Arthur comes to visit Ywain, Ywain's pride is first in his land, then in his wife. Alundyne's gesture may appear to be mercenary, but the entire romance of Ywain is more concerned with property and titles than less pragmatic things such as love and marriage.

The overall narrative structure of Ywain is the same as it is in other Yvain romances, but its emphasis on politics reflects the realities of the intrigue at court. From the vassal point of view, Alundyne's repeated consultation of her barons is idealized behavior, in accordance to the social norms of England at the time.55 The poet inserts an additional insult in Luned's accusation when Ywain breaks his vow; she says that a man who forgets his wife so soon cannot be one who is born of a king's bloodline. If Hartmann's Iwein is a happy balance between the idealistic and the pragmatic, Ywain is strictly on the pragmatic side, with the final reconciliation telling the audience that Ywain has regained his lordship and dominion.

This is not to say that Ywain ignores matters of love. Love is there, and the relationships between the characters are still present. The author seems to be operating from an assumption that his audience is familiar with the concepts of courtly love, and many residual details from Chrétien are left without any alterations. However, the author does appear to have a particular distaste for monologue and expressive introspection, choosing to simply omit or reduce these episodes to the best of his ability while still maintaining coherence.56 The overall effect produced is a piece that may feel like a shadow of its former self but nonetheless makes itself distinct. Given the unique changing social circumstances, where the old systems of feudal stewardship are slowly collapsing, the curt tone and reductions of Chrétien's concerns should not be surprising. One may as well say that Ywain and Gawain is an adventure in English politic and courtly intrigue rather than a tale of love, and that person would not be too far from the truth.

Malory