While these resources will remain accessible during the course of migration, they will be static, with reduced functionality. They will not be updated during this time. We anticipate the migration project to be complete by Summer 2025.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us directly at robbins@ur.rochester.edu. We appreciate your understanding and patience.

The Fisher King

1 Nitze, William A. "Who Was the Fisher King? A Note on Halieutics." Romanic Review 33 (1942): 103: Nitze sees in the father of the Fisher King a resemblance to the Greek god Cronos, who is referred to as a harvest god because of his association with the mythological Golden Age. Cronos overthrew Uranus, his father, by castrating him with a sickle, only to be later overthrown by his son, Zeus. Cronos was then imprisoned in Tartarus until Zeus released him and made him the ruler of the Underworld.

2 It is worth noting that the Fisher King does not declare that mending the Broken Sword will heal him of his wounds. Instead, as the text later reveals (192-93), the task proves one worthy enough to learn about the history of the Broken Sword.

3 Bryant connects the knight and the Fisher King in his table of contents: "Gawain . . . comes to . . . the Grail Castle; he again fails to mend the Broken Sword, and falls asleep as the Fisher King tells him the truth about the Bleeding Lance" (vi).

4 Gerbert de Montreuil's Continuation is also known as The Fourth Continuation.

5 The introduction of Joseph of Arimathea and of his connection to the Grail legend may have been influenced by Robert de Boron's Joseph of Arimathea.

6 Both The Second and The Fourth Continuations end in exactly the same way:

"My good, dear friend, be lord of my house. I willingly bestow upon you everything I have, and henceforth will hold you dearer than any man alive."

At that the boy who had brought the sword hurriedly returned, and took it and wrapped it in a silken cloth and carried it away; and Perceval felt greatly comforted (193, 270)

This suggests that both Continuations might have been two versions of one story or that the repetition of these last lines serves some looping function. For an interesting discussion on the structure of these Continuations, see Matilda Tomaryn Bruckner's essay, "Looping the Loop through a Tale of Beginnings, Middles, and Ends: From Chrétien to Gerbert in the Perceval Continuations," where she argues for the existence of unity among these Continuations.

7 For a discussion on the influence of Chrétien's Perceval on the Perlesvaus, see Norris J. Lacy's essay, "Perlesvaus and the Perceval Palimpsest," in Groos and Lacy, where Lacy sees Perceval as a subtext for the author of the Perlesvaus to "systematically ['rewrite'] and ['reinterpret']" (Groos 98).

8 Carman, J. Neale. "The Symbolism of the Perlesvaus." PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association. 61:1 (1946): 42-83. Carman explores the use of Christian symbolism in Perlesvaus. He connects the Fisher King with Christ himself, noting his name, Messios, his function as a sufferer, and his death symbolizing the Crucifixion (47).

9 Robert de Boron's work exists in both Robert's original verse and later prose adaptations. Of the verse form, only Joseph of Arimathea and fragments of Merlin have survived. The prose adaptations of these two romances are complete and are followed by a Perceval; however, there is speculation about whether or not Robert de Boron actually wrote Perceval. Based on the Didot manuscript, the work is commonly referred to as the Didot-Perceval. For this essay, I have used the prose adaptations of Robert's work.

10 Here is a chronological list of the Rich Fishermen: Alan, Joshua, Aminadap, Carcelois, Manuel, Lambor, and Pellehan (Lacy 1: 159-60).

11 See Lacy 1: 78-85 for the background of Solomon's ship and, in particular, its connection to the Tree of Life.

12 On p. 80, Sigune erroneously counts four children from Frimutel. Trevrizent counts five children (152-53).

13 Lacy, Norris. Lancelot-Grail. The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation. Vol. IV. New York: Garland, 1995: 211-14: this episode in the Vulgate provides Malory's source of the story of the Dolorous Stroke.

14 See David Tomlinson's essay, "T. S. Eliot and the Cubists," in Twentieth Century Literature: A Scholarly Journal 26:1 (1980), for a thorough discussion on the influence of Cubism on Eliot and The Waste Land.

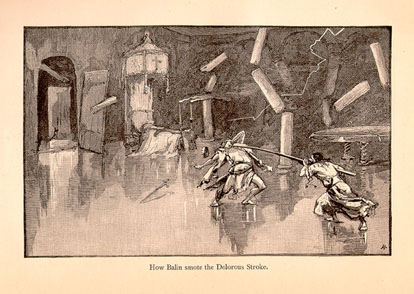

15 This line itself is an allusion to Isaiah 38:1: "Thus saith the Lord, Set thine house in order: for thou shalt die and not live."

16 Perceval at the Grail Castle. Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. FR 12577. Conte Del Graal. c. 1330.

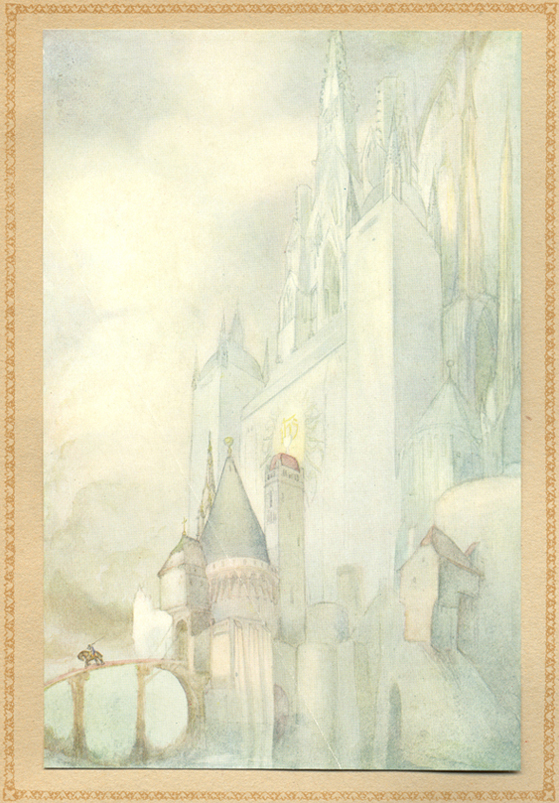

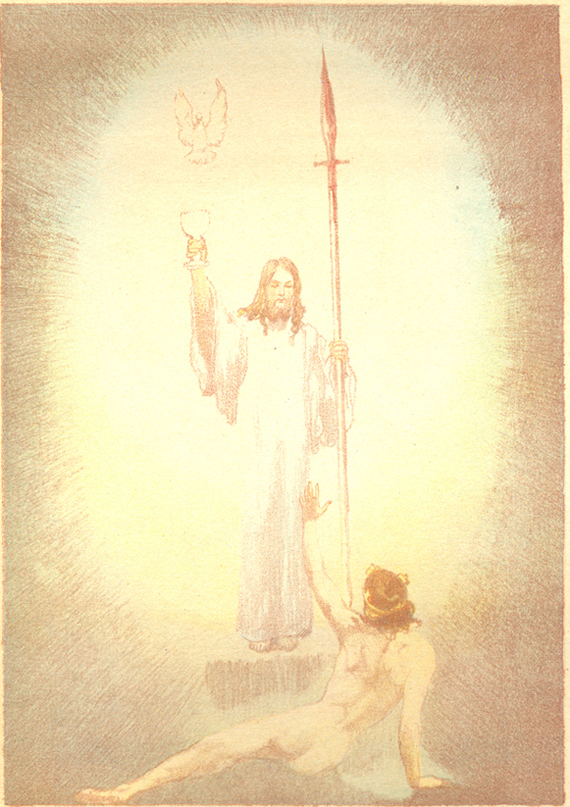

17 Heidelberg, Codex Palatinus Germanicus 339, f. 27. Parzival. 1440-1450.

18 Vienna, Nationalbibliothek 2914, f. 359. Parzival. 1440-1450.

19 See William Pogany in the Camelot Project.

20 Ferguson, Anna-Marie. The Dolorous Stroke.

21 Ferguson, Anna-Marie. King Evelake.

22 Parsifal's Encounter with the Fisher King and Parsifal in Montsalvat, the Castle of the Holy Grail can be seen on Arthurian Legends Illustrated, Part IV: Healing the Fisher King by Kathleen L. Nichols. In her captions, Nichols notes that Parsifal's Encounter with the Fisher King was painted by one of two artists—either August Spiess or Ferdinand Piloty (Nichols). Parsifal in Montsalvat is attributed definitively to Spiess by both Nichols and the creators of the Neuschwanstein Castle website. Neuschwanstein Castle, Bavaria.

- Introduction

- Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval

- The First Continuation of Perceval

- The Second Continuation of Perceval

- Gerbert de Montreuil's Contination

- The Third Contination of Perceval

- The Conclusion to Perceval

- Perlesvaus

- Robert de Boron

- The Vulgate Cycle

- Peredur Son of Evrawg

- Parzival

- Malory's Morte Darthur

- Between Malory and Eliot

- T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land

- Bernard Malamud's The Natural

- In Country and Park's Quest

- The Fisher King in Art

- The Fisher King in Film

The mysterious Fisher King is a character of the Arthurian tradition, and his story may sound familiar: suffering from wounds, the Fisher King depends for his healing on the successful completion of the hero's task. There are many different versions of the story of the Fisher King, and the character is not represented uniformly in every text. In the medieval period, Chrétien de Troyes' Percival makes him a completely ambiguous figure, while Wolfram von Eschenbach provides him an elaborate background in his Parzival. The Vulgate Cycle expands the Fisher King into multiple Maimed Kings, each suffering from some type of wound; yet Thomas Malory virtually ignores the Fisher King in his Morte Darthur. Modern texts treat the Fisher King less as a character and more as a motif: T. S. Eliot incorporates the motif of the Fisher King into the desolated modern city and its people in his poem, The Waste Land; in other modern texts, the Fisher King is embodied in a Vietnam War veteran, children in search of their fathers' identities, and the baseball coach of a team on a hopeless losing streak. The Fisher King also appears in various films, from Eric Rohmer's adaptation of Chrétien's Perceval to Terry Gilliam's buddy comedy, The Fisher King. In every version of the story, though, the Fisher King is completely helpless and depends on another to alleviate his suffering.

Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval

As a literary character, the Fisher King originates in Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval. The reader first encounters the Fisher King when Perceval meets a fisherman who offers Perceval lodging. In his castle, the fisherman reveals himself to be a king who is weak and bedridden, and yet has such an abundance of wealth that he can provide his guest a grand feast. During the feast, Perceval witnesses a Grail Procession but fails to ask his host any questions pertaining to what he sees. As a result, all the inhabitants of the castle disappear the next morning (Chrétien de Troyes 32-37).

As a literary character, the Fisher King originates in Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval. The reader first encounters the Fisher King when Perceval meets a fisherman who offers Perceval lodging. In his castle, the fisherman reveals himself to be a king who is weak and bedridden, and yet has such an abundance of wealth that he can provide his guest a grand feast. During the feast, Perceval witnesses a Grail Procession but fails to ask his host any questions pertaining to what he sees. As a result, all the inhabitants of the castle disappear the next morning (Chrétien de Troyes 32-37).

The fisherman is later said to be the rich Fisher King who "was wounded in a battle and completely crippled, so that he's helpless now, for he was struck by a javelin through both his thighs; and he still suffers from it so much that he can't mount a horse. But when he wants to engage in some pleasure and sport he has himself placed in a boat and goes fishing with a hook" (38). His healing depends on Perceval and his asking of the necessary Grail questions, such as "who does the Grail serve?" and "what is the meaning of the Bleeding Lance?" (38-39). This description, of a suffering king who depends for his healing on another person, becomes the prototype for all variations of the Fisher King in literature.

In Chrétien's Perceval, there appears to be confusion between the Fisher King and his father, who may or may not be a Grail King:

And I believe the rich Fisher King is the son of the king who is served from the grail . . . he's served with a single host which is brought to him in that grail. It comforts and sustains his life—the grail is such a holy thing. And he, who is so spiritual that he needs no more in his life than the host that comes in the grail, has lived there for twelve years without ever leaving the chamber which you saw the grail enter. (69)

Chrétien does not include any specific references to the Fisher King as the keeper of the Grail; however, the Grail is kept in his castle, which is commonly referred to as the Grail Castle. The description of the father of the Fisher King, though, suggests that the mysteries of the Grail are directly linked to him: the Grail Procession enters and exits his room and he has been sustained by its host. Other than by describing him as a very spiritual man, Chrétien does not explain why the Fisher King's father has been served by the Grail. Is he also wounded? More importantly, what is his connection to his son, the Fisher King?1

The role of Chrétien's Fisher King, suggested by his mystical and spiritual relationship with the Grail, is to assess the level of Perceval's spiritual purification. Only the worthiest knight, one who has moved away from worldly adventures to spiritual quests, can heal his suffering. Perceval's failure to ask the Grail Questions is a result of his moral immaturity. Before he may be deemed worthy, Perceval must first acknowledge and then cleanse the sin of the abandonment of his mother, the act which caused her to die from grief (68-9).

Chrétien de Troyes died before finishing Perceval, so other writers took on the task of completing his story. In The First Continuation, the Fisher King maintains his role in assessing the worthy knight; however, as different writers expand upon Chrétien's work, various changes, sometimes inconsistent, are made to the Fisher King: his appearance has sometimes been altered to suggest that he is not maimed (130), and new tasks, such as the mending of the Broken Sword, must be completed.

In The First Continuation, Gawain's adventures encompass the entire story: his character functions as a foil to Perceval in his movement toward becoming a spiritual knight. Gawain takes lodging in the castle of the Fisher King and witnesses the Grail Procession, which now includes the Bier that contains an unknown body, and the Broken Sword, which lies upon the Bier.

Unlike Perceval, Gawain does ask the Grail Questions; however, this act does not heal the Fisher King. Instead, the Fisher King requires Gawain, in order to prove himself to be the worthiest knight, to mend the Broken Sword before he may reveal the answers to his questions. 2 Gawain connects the broken pieces of the sword but the pieces come apart again, proving Gawain to be less than perfect. The Fisher King explains that Gawain has "not yet achieved enough as a knight to know the truth about these things" (113). Gawain wakes up the next morning not in the castle but at a marsh (111-13).

Gawain then takes on the quest of a dead knight: he comes to the Grail Castle, with the Bleeding Lance, the Grail, and the Bier with the Broken Sword lying upon it; however, he is met by a very different figure from the Fisher King, a "tall and strong-limbed knight" 3 (130). He requires Gawain to complete his quest by mending the Broken Sword. Gawain fails to do so; however, his efforts have partially restored vitality to the kingdom (124-32).

The task of mending the Broken Sword, like the asking of the necessary Grail questions, is a method to evaluate the worthy knight. Gawain's failure to perfectly mend the Broken Sword is similar to Perceval's failure to ask the Grail Questions: both knights possess flaws that prevent them from succeeding; however, Gawain's being charged with treason (52) and his attempt to seduce a damsel in a tower (62-3) suggest that he possesses spiritual flaws. Gawain's failure sets up further Continuations that concentrate on Perceval's growth as a knight.

In The Second Continuation, the story shifts back to Perceval and his quest to learn about the Grail: Perceval is no longer prohibited from asking the Grail Questions, but, as with Gawain, this is not (or perhaps this is no longer) sufficient to heal the wounds of the Fisher King. After proving himself worthy as a worldly knight (163-73), Perceval returns to the Grail Castle and asks the Grail Questions, along with questions about a vision of a child that he witnessed during his journey (182-83). The Fisher King interprets this vision as an indication that Perceval is not yet proven as a spiritual knight, so, therefore, Perceval is not yet worthy to hear the secrets of the Grail (191-92).

Perceval then inquires about the Broken Sword, but, like Gawain, he is required to mend the sword before he may learn of its history. Perceval mends all but a very small notch in the sword. The Fisher King interprets this as a sign that Perceval, although proven to be unmatched as a worldly knight, must now prove himself to God as a spiritual knight. Even so, the Fisher King, so convinced is he of Perceval's worthiness, willingly bestows everything he has upon the young knight (192-93).

In Gerbert de Montreuil's Continuation, the Fisher King requires Perceval to repair the notch in the sword before he may learn the secrets of the Grail and of the Bleeding Lance; yet, he acknowledges that Perceval is the only one who is worthy of learning these secrets. He reminds Perceval of his need to atone for the sin of abandoning his mother, and Perceval goes on a spiritual journey to cleanse his soul (194). Before he leaves, Perceval learns that his asking of the Grail Questions, although they had not led to either any answers or the healing of the wounded Fisher King, had restored vitality to the wastelands that surround the kingdom (198).

During his quest for spiritual growth, Perceval comes upon King Mordrain, another wounded king—a Maimed King—and one who has close ties to the Fisher King: Mordrain had rescued Joseph of Arimathea 5 from imprisonment by the cruel King Crudel. As Mordrain had attempted to look at the Grail, which Joseph himself carried, an angel from heaven struck him down with a fiery sword, declaring that Mordrain was too stained with sin to be considered worthy enough to witness the Grail. Mordrain's wounds, like those of the Fisher King, would therefore never heal, nor would Mordrain ever die, until Perceval comes to cure him (256-57). The introduction of the story of Joseph of Arimathea and his connections with the Grail bring greater historical significance to the Grail itself. We have seen it as a sustainer of life in Chrétien (69) and as a beacon of light in the Second Continuation (160), but with the addition of the identification of the Grail as the cup that caught Christ's blood as he hung on the Cross, the spiritual importance of the Grail quest, as well as the mystical nature of the Fisher King, has greatly increased. After the trials that tested and cleansed Perceval's soul, making him holy and worthy before God, he returns to the castle of the Fisher King for the third time. He mends the notch in the Broken Sword and brings great joy to the Fisher King, who again grants lordship of all that he has to Perceval (269-70). 6

The story of Perceval is brought to an end again in The Third Continuation, as Perceval learns the secrets of the Grail, of the Bleeding Lance, of the Silver Trencher, and of the Broken Sword. The Fisher King reveals that he is descended from Joseph of Arimathea and is thus a Grail King. The Broken Sword came about as Partinial the Wild, disguised, tricked and killed King Gon of Sert, the brother of the Fisher King: it is Gon's body that lies on the Bier. The sword shattered from the fatal blow and could not be repaired by anyone other than Perceval. Grieving over the murder of his brother, the Fisher King stabbed himself with pieces of the Broken Sword, leaving him helpless and crippled (271-75). Perceval avenges the Fisher King by beheading Partinial; in doing so, he finally heals the wounds of the Fisher King. At the end of Perceval, the Fisher King learns of Perceval's name and of their familial bond; and after he dies, Perceval inherits his kingdom and becomes the new Grail King (297-302).

With The Third Continuation, the wounding of the Fisher King has been changed from a javelin thrust to self-inflicted wounds by pieces of the Broken Sword. This change, to set up Perceval's quest to avenge the Fisher King, takes away from the mystical connection with the Grail. The need for revenge to heal the Fisher King is problematic in regards to maintaining a sense of unity between Chrétien's Perceval and the Continuations: since Perceval had been instructed to transcend such worldly values (284-85), the requirement to slay Partinial appears to be a drastic step back for his quest to become spiritually pure.

There are other inconsistencies between Chrétien's text and the subsequent Continuations: in Chrétien's text, the Fisher King would have been healed if Perceval had asked the necessary Grail Questions (39), but in The Second Continuation, and even more so in The Third Continuation, the method used to heal him has changed, as the Broken Sword must now be mended and the Fisher King must be avenged. Perhaps this is an attempt to create cohesion between Perceval's and Gawain's adventures. At first glance, The Second and The Fourth Continuations appear to be two different attempts to link The First and The Third Continuations together; however, although they are structurally similar, there is consistency in Perceval's growth from a worldly to a spiritual knight.

Familial relations play an essential role for the major characters of Perceval. The Fisher King is Perceval's uncle and, therefore, the Fisher King's father is Perceval's grandfather (69). Perceval's father, the brother-in-law to the Fisher King, suffers a similar wounding, through one of his legs (6). Other members of Perceval's family—his sister and his hermit uncle—are essential in helping Perceval in his quest to heal the Fisher King. In the Continuations, the importance of familial relations continues to permeate the texts as multiple wounded figures—Perceval's father, Mordrain, the Fisher King—connect to each other through their blood relations and through their importance to the Grail. In each case, the wounded figure depends upon a blood relative to cure him.

The character of the Fisher King has undergone changes from Chrétien's text to the subsequent Continuations, but in each form, there remains the figure of a king who suffers from wounds that affect his lands and that can only be healed by a proven knight. This becomes the basis for further depictions of the Fisher King character in the Arthurian canon.

The Perlesvaus, a thirteenth century romance by an unknown author, can be looked upon as a loose reworking and continuation of Chrétien's Perceval 7; however, Perlesvaus radically departs from Perceval and its subsequent Continuations as the story takes a strange, violent turn from the Perceval legend: a bloody religious war between the Old Law and the New Law pervades the text, which depicts extreme acts of violence. Perceval departs from the chivalric growth associated with Chrétien's Perceval and becomes the Good Knight, a spiritual and chaste knight who is fated to restore peace to Britain. Perceval's characterization may suggest a connection with Galahad from the Vulgate Cycle; however, it is, at most, a small connection: his role as a "soldier of our Lord" (Evans 216), who slaughters those who do not convert to the New Law, differs greatly from Galahad's role as a peaceful guardian of the Grail.

The Fisher King has an important, albeit small, role in Perlesvaus. He is described as:

[lying] on a bed hung on cords whereof the stays were of ivory; and therein was a mattress of straw where he lay, and above a coverlid of sables whereof the cloth was right rich. And he had a cap of sables on his head covered with a red samite of silk, and a golden cross, and under his head was a pillow all smelling sweet of balm, and at the four corners of the pillow were four stones that gave out a right great brightness of light; and over against him was a pillar of copper whereon sate an eagle that held a cross of gold wherein was a piece of the true cross whereon God was set, as long as was the cross itself, the which the good man adored. (Evans 86)

The Fisher King does not suffer from being wounded; rather, he falls into languishment because Perceval failed to ask him the Grail Question (24). Perceval's failure to ask the Grail Question has other consequences: Arthur becomes a feeble king (3-21), Britain's lands turn to waste (2), and its kingdoms, along with its knights, war against each other (24). Not knowing the identity of the knight who caused him his suffering, the Fisher King awaits the arrival of a worthy knight to heal him by asking the Grail Question. Two other knights attempt to cure him but fail: Gawain, mesmerized by the Grail Procession, fails to ask the Grail Question (88-90); Lancelot, because of his affair with Guinevere, is denied the opportunity to see the Grail (134-35).

The Fisher King is part of a genealogy that begins with his uncle, Joseph of Arimathea. He has two brothers, King Pelles and the King of Castle Mortal, and a sister, Yglais. King Pelles renounces his kingdom and becomes a religious hermit after the murder of his wife by his son, Joseus (40). The King of Castle Mortal, described as wicked, wars upon the Fisher King over possession of the Grail (40). Yglais, the Widow Lady, is Perceval's mother and the widow of Alain li Gros. She waits for Perceval's return to save her castle from attacks by the Lord of the Moors (38).

In contrast with his counterpart in other works, The Fisher King of the Perlesvaus is not healed but dies (185) before Perceval returns to conquer the Grail Castle (223-28). The body of the Fisher King lies in a richly decorated sepulcher, where "as soon as the body was placed in the coffin and [the priests and knights] were departed thence, they found on their return that it was covered by the tabernacle all dight as richly as it is now to be seen . . . and they say that every night was there a great brightness of light as of candles there, and they know not whence it should come save of God" (229).

God's ceremonial decoration of the Fisher King's tomb suggests that his death had great spiritual significance: Josephus recounts the tale of Cain and Abel to illustrate that although the King of Castle Mortal comes from the good lineage of Joseph of Arimathea, it is possible for him to become evil; however, since the Fisher King, through his suffering, did not yield to his brother's evil, he became a spiritual model for others to follow (227-28). 8

Although Gerbert de Montreuil's Continuation of Perceval introduces a connection between the Fisher King and Christianity, the Perlesvaus, Robert de Boron, and the Vulgate Cycle make the connection a central part of their works. Robert de Boron wrote his Arthurian cycle in the early thirteenth century, not long after Chrétien's Perceval was written. One can see Chrétien's influence on Robert de Boron, particularly in the Grail quest itself; however, in writing Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, and Perceval, 9 Robert incorporates Christian Biblical history within the Arthurian legend and thus distinguishes his works from Chrétien's Perceval. Robert also moves away from the violent nature of the Perlesvaus, focusing not on religious war but on the characters themselves and the importance of genealogy. Joseph of Arimathea is closely associated with Jesus Christ, as he "had seen Him as a little child and in the temple where He had disputed with the elders . . . [and] he had seen Him crucified" (Robert de Boron 155). The Grail has become more significant, as it is identified as the cup that was used at the Last Supper (19). There is no mention of the Fisher King's father, which created confusion in Chrétien's Perceval as to who was the guardian of the Grail. Robert de Boron makes it clear that the Fisher King is its guardian (42).

Robert de Boron provides the Fisher King with an identity and a history: his name is Bron, and he is the brother-in-law of Joseph of Arimathea (34), a soldier who converts to Christianity. After Christ's crucifixion, Joseph takes His body down from the Cross and then buries Him (18-19). Pilate gives Joseph the Grail, and Joseph uses it to collect Christ's blood as it falls from His body on the Cross (19).

Bron earns the name of the rich Fisher King when God commands him to catch a fish to feed his followers (35). Bron does so and God's messenger calls him the rich Fisher King "because of the fish he caught" (42). Bron also becomes the guardian of the Grail and takes it to the West, where he "must await the coming of his son's son" (Alain li Gros and Perceval, respectively), (43) to whom he will then transfer the guardianship of the Grail.

Instead of suffering from a wound, Robert de Boron's Fisher King suffers from a malady that can only be healed by Perceval, his grandson (113). Perceval's immaturity causes him to refrain from asking the Grail question that would have healed the Fisher King during his first visit to the Fisher King (141). After Perceval proves his worthiness, he returns to the Fisher King and heals his grandfather by asking the Grail Question. Bron passes on the guardianship of the Grail to Perceval and dies three days later, after which Perceval becomes known as the Fisher King. Thus, the Fisher King is not necessarily associated with Bron himself but with the Grail guardian, whoever he may be (154-55).

The Vulgate Cycle builds on Robert de Boron's development of the Fisher King and his genealogy: there are multiple Fisher Kings, or Rich Fishermen. The Vulgate, though, focuses on ecclesiastical uses of its characters and the Grail Quest, as knights are morally instructed through their various adventures and visions. In addition to its moral purposes, the Vulgate also introduces multiple Maimed Kings that differ from the Rich Fishermen.

The Vulgate Cycle builds on Robert de Boron's development of the Fisher King and his genealogy: there are multiple Fisher Kings, or Rich Fishermen. The Vulgate, though, focuses on ecclesiastical uses of its characters and the Grail Quest, as knights are morally instructed through their various adventures and visions. In addition to its moral purposes, the Vulgate also introduces multiple Maimed Kings that differ from the Rich Fishermen.

The History of the Holy Grail closely follows Robert de Boron in some details: Joseph of Arimathea is given the Holy Grail after his services to Christ, and Jews imprison Joseph after Christ's resurrection, suspecting him of treachery. Joseph is imprisoned for forty-two years, rather than for a matter of days, as in Robert de Boron (Lacy 1: 11). Because Joseph was sustained by the Grail during his imprisonment, when he is finally released, he appears not to have aged at all (1: 13).

The Vulgate Cycle establishes a timeline of approximately 400 years between the time of Joseph of Arimathea and the Grail Quest: Josephus' return to minister the Grail mass is described as occurring three hundred years after his time (4: 84); 400 years pass between the moment of Mordrain's blinding and his visit by Galahad (4: 29).

Joseph and his son, Josephus, bring the Grail to other lands and they convert their inhabitants to Christianity. Josephus suffers from a wounding that is quite similar to that suffered by the Maimed King, as an angel strikes him with a lance through his left thigh when he tries to stop the killing of the inhabitants of a city who would not convert to Christianity. The tip of the lance breaks off and remains in Josephus' leg, causing him to walk with a limp and to have a wound that bleeds incessantly. Only after he baptizes an entire city is Josephus deemed cleansed of his sin, and an angel removes the tip of the lance from his leg (1: 49-51).

Bron does not become known as the Fisher King in The Vulgate Cycle; rather, his son, Alan the Fat, earns the name. Alan, the keeper of the Grail after Josephus (1: 157), follows Jospehus' command to "go to the pond and get in the little boat; throw the net you will find there into the water and catch a fish" (1: 139). Alan catches a single fish that God multiplies to feed His followers. The followers, rejoicing in their great fortune, revere Alan:

Because of the great plenty that they had had from the gift of the fish Alan had caught, they gave him a name that was never abandoned, for they called him the Rich Fisherman. Thereafter he was called more often by that name than by his right name. And in his honor and because of that day's grace, all those who were invested with the Holy Vessel were called Rich Fishermen (1: 140). 10

Alan brings the Grail west to a place called the Land Beyond and establishes the Grail castle of Corbenic. Joshua, Alan's brother, becomes its king and, after Alan dies, he becomes the guardian of the Grail, the Rich Fisherman (1: 158-59).

After King Joshua, his son Aminadap rules and marries the daughter of the king of the Land Beyond. Aminadap fathers King Carcelois, who becomes known for his prowess as a great knight, as well for as his worthiness to God. After Carcelois, his son King Manuel rules, who then fathers King Lambor (1: 159).

King Lambor, who was supremely devoted to God, warred with Varlan, his neighbor. During one battle, Varlan flees after all of his men are killed. He discovers Solomon's ship 11 and takes The Sword of the Strange Straps from it. Varlan finds Lambor and kills him with the sword. God avenges Lambor's murder by turning the kingdoms of the Land Beyond and Wales into the Waste Land. As Varlan returns the Sword of the Strange Straps to its scabbard, he falls dead (1: 159-60).

In the History, Pellehan, Lambor's son and successor, suffers from a wounding in both of his thighs from a battle in Rome; thus the wound is not linked to the Grail story. Because of his wounding, Pellehan becomes known as the Maimed King, and his wound will not heal until Galahad comes to see him (1: 160). In the Quest, Pellehan discovers Solomon's ship and comes aboard it. He partially draws The Sword of the Strange Straps from its scabbard and a lance wounds Pellehan between his thighs because of his audacity (4: 66). These two wounds appear to be distinct from each other. From Pellehan descends Pelles, whose daughter couples with Lancelot to bring Galahad into being (1: 160).

Along with multiple Rich Fishermen, multiple Maimed Kings, besides Pellehan, exist in the Vulgate Cycle. King Mordrain, because he wished to see the Grail, comes too close to it. God punishes him for ignoring the command not to approach the Grail by depleting his strength and by blinding him (4: 135). King Alphassan, who built Corbenic castle for Alan and Joshua, makes the mistake of sleeping in the Palace of Adventures, where the Grail is being kept, and is wounded by a lance through both his thighs (1: 159). Of all these Maimed Kings, Pellehan is the only one who is also a Rich Fisherman.

Other figures in the Vulgate suffer from wounds that resemble those of the Maimed Kings: Nascien, although not a king, is struck by a sword through his shoulder in punishment for drawing The Sword of the Strange Straps from its scabbard (4: 66). Lancelot is struck by a fire and is unconscious for twenty-four days after he disobeys God and tries to come close to the Grail (4: 80), Josephus, as was already explained above, is wounded by a lance for disobeying God (1: 49-51).

In the Quest, Galahad replaces Perceval as the successful Grail knight and the healer of the Maimed Kings. While in Chrétien's romance, Perceval undergoes a spiritual quest before being deemed worthy to heal the maimed Fisher King, the Vulgate's Galahad is a pure knight who is detached from worldly duty, has no feudal obligations, and is not concerned with corporeal pleasure. In speaking of Galahad's beauty, Lancelot says that he has "never seen anyone so perfectly formed" (4: 3). Jean Frappier comments that Galahad's perfection is "unreal; a saint untroubled by temptation, a foreordained Savior" (Loomis Arthurian Tradition in the Middle Ages: A Collaborative History 305). Galahad succeeds in trials at which other knights fail: he is able to sit in the Perilous Seat (4: 5-6); he easily removes a sword from a stone, which marks him as the world's best knight (4: 4-6); he is the only one worthy to wear the shield of Mordrain (4: 12-13). In the Vulgate, Galahad is named as the one who will heal the Maimed King: Joseph learns that a man (Pellehan) will be struck by the Holy Lance and will not be healed until the coming of Galahad (1: 51); God also promises Mordrain that Galahad will restore his health (4: 29).

Before he goes to Corbenic, Galahad visits Mordrain. As Galahad comes near, Mordrain's eyesight returns to him and his health is restored. Feeling fulfilled by seeing the knight that he had long waited for, Mordrain embraces Galahad and dies in his arms (4: 82). Galahad then visits Corbenic, repairs the Broken Sword, and witnesses the Grail Procession. An unknown man, perhaps another Maimed King, tells Galahad that he had been waiting to see him. Now that he has seen him, he is ready to die. After the man dies, Josephus returns from Heaven and ministers the Holy Mass. Finally, Jesus appears and reveals the secrets of the Grail to Galahad. Galahad heals Pellehan by anointing his legs with the blood from the Holy Lance. After being healed, Pellehan, the last of the Rich Fishermen, joins a community of white monks and is heard from no more (82-85).

Scholars do not agree on either the existence or the identity of the unknown Maimed King. In his essay, "The Vulgate Cycle," Jean Frappier refers to only one Maimed King in the Quest (Loomis Arthurian Tradition in the Middle Ages 303). In her book, Galahad in English Literature, Sister Mary Louis Morgan makes no distinction between the two Maimed Kings. Morgan and Frappier may have intentionally ignored the existence of two Maimed Kings to avoid the issue of trying to resolve the identity of the unknown Maimed King. Frederick W. Locke describes the existence of two separate figures as a fracturing of the Maimed King from the Fisher King; he argues that the presence of two figures provides dramatic intensification as Galahad heals one after the other (Locke 81-82).

The Vulgate Cycle multiplies one Fisher King into a family of Rich Fishermen and also into multiple other Maimed Kings; various types of wounds occur throughout the text, mainly in regards to various types of moral instruction. As the Perceval legend branches out into Welsh literature, regional gods and beliefs replace Christian interpretations of the Fisher King.

Peredur Son of Evrawg provides a Welsh interpretation of the Perceval legend, and there is much debate on how much of an influence Welsh literature had on Chrétien, and vice versa. In Arthurian Tradition and Chrétien de Troyes, R. S. Loomis examines the Welsh background of Chrétien's Perceval and sees similarities between the Fisher King and Bran, a Welsh sea-god. William A. Nitze agrees with Loomis, and in his essay, "The Fisher King and the Grail in Retrospect," he sees traces of the Irish characters Nuadu (Welsh, Nudd) and Tuatha Dé Danann in the Fisher King. Chrétien acknowledges that Perceval le Gallois is a Welshman—"le gallois" is French for "the Welsh man." In both stories, a young man, Peredur or Perceval, learns how to become a knight and goes on a quest to heal a wounded king. But the Lame King of Peredur has some major differences from the Fisher King of Perceval.

In Peredur, there are two kings, who are brothers to each other and maternal uncles to Peredur. The kings are described as lame but not as invalids. One of the two kings is able to stand and walk to the castle. He does not lie in a bed but sits on a cushion (Gantz 224). The second king is seen sitting at a table (225). Neither of the kings is given the name of Fisher King; however, Peredur sees his first uncle sitting on a boat, while others in the boat are fishing (224).

After Peredur proves his prowess at fighting with a cudgel and a shield, his first uncle teaches him manners and courtesy: "though what you see is strange, do not ask about it unless someone is courteous enough to tell you; any rebuke will fall on me rather than on you, as I am your teacher" (225). The uncle's advice to Peredur, similar to that in Perceval, indicates his awareness of Peredur's immaturity, and he may have thought that Perceval was not yet ready to know about the wonders that he will see at his second uncle's castle.

Peredur rides from his first uncle's castle and meets his second uncle, who is sitting at a table. After sharing a feast, Peredur's uncle instructs him on how to use a sword by striking it against an iron column. As Peredur strikes the column with his sword, the column and the sword both break in two. Peredur's uncle tells him to rejoin the sword and the column, and then to strike the column again. Peredur does so again; when he strikes the column with his sword for a third time, Peredur is unable to rejoin either the sword or the column. Peredur's uncle tells him that this test indicates that he has developed two parts of his strength, with the remaining part yet to come (225-26).

Peredur then witnesses a procession of a bleeding spear and a large salver that contains a bloody severed head. Peredur wishes to know the meaning of the things he has seen, but remembering his other uncle's advice, he chooses to wait until his uncle provides an explanation. Since his uncle does not provide an explanation to these wonders, Peredur remains quiet (226).

Later, the Black Maiden (the equivalent of the Loathly Lady of Perceval) reproaches Peredur for not inquiring about the wonders he witnessed, for "had [he] asked, the king would have been made well and the kingdom made peaceful, but now there will be battles and killing, knights lost and women widowed and children orphaned" (249). Peredur then goes to search for his uncle's castle.

When Peredur returns to the castle of the Lame King, he learns that the severed head belongs to his cousin, who was murdered by the hags of Gloucester. This is inconsistent with the story, however, since Peredur is told about these mysteries before he has had a chance to ask any questions. Fulfilling a prophecy, Peredur avenges his cousin and his uncle by slaying the hags. There is no indication that the Lame King, either as a result of Peredur's return to his castle or as a result of his vengeance against the hags, is restored to health (254-55).

Although Peredur has some major differences from Chrétien's Perceval, Wolfram von Eschenbach completely reworks and reinterprets Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval in his work, Parzival. Although the basic storyline of Perceval is followed, Wolfram denies Chrétien's influence on his work; instead, he claims that Kyot, "who saw this adventure of Parzival written down from heathen tongue" (Wolfram von Eschenbach 134), originated the Perceval legend. Wolfram mentions Chrétien as having "done this tale an injustice" (264), and credits himself with finishing the "tale [that] has been kept locked away" (233), a reference to Chrétien's unfinished story; however, as Cyril Edwards states in the introduction to his translation of Parzival, scholars doubt the existence of Kyot and speculate that Wolfram invented Kyot to mask Chrétien's influence (xxii).

In Wolfram's romance, Anfortas is the wounded Grail King of Munsalvaesche, a mysterious castle that cannot be easily found. An army of Grail knights defends the castle and its lands, the Terre de Salvaesche (91). Anfortas is so rich that he wears "such clothing that even if all lands served him, it could be no better" (72). As the Fisher King is Perceval's uncle in Chrétien's Perceval, so is Anfortas to Parzival, and his healing depends on Parzival's asking of the Grail Question, which in this case is: "Uncle, what troubles you?" (254). Distancing himself from Chrétien, Wolfram does not call Anfortas the Fisher King, but because fishing is an activity that soothes his pain, "a tale emerged that he is a fisherman. That tale he has to bear with" (157).

Anfortas is a member of a Grail dynasty that begins with Titurel, the first Grail King of Munsalvaesche. Frimutel, his son, inherited Munsalvaesche after Titurel's death. Frimutel, a "noble warrior" (80) who died as a result of a joust over love, had five 12 children: Anfortas, who inherits Munsalvaesche and becomes Grail king after Frimutel; Trevrizent, who renounces his wealth and becomes a servant to God; Herzeloyde, mother to Parzival; Schoysiane, mother to Sigune; and Repanse de Schoye, the Grail-bearer (80). After Parzival heals Anfortas, he inherits Munsalvaesche and becomes the Grail King (254).

Anfortas is a member of a Grail dynasty that begins with Titurel, the first Grail King of Munsalvaesche. Frimutel, his son, inherited Munsalvaesche after Titurel's death. Frimutel, a "noble warrior" (80) who died as a result of a joust over love, had five 12 children: Anfortas, who inherits Munsalvaesche and becomes Grail king after Frimutel; Trevrizent, who renounces his wealth and becomes a servant to God; Herzeloyde, mother to Parzival; Schoysiane, mother to Sigune; and Repanse de Schoye, the Grail-bearer (80). After Parzival heals Anfortas, he inherits Munsalvaesche and becomes the Grail King (254).

Anfortas' wounding happened because of his desire for love and adventure: while in a joust, he was wounded in his genitals by a poisoned spear. Anfortas' attempt to heal himself with the Grail fails: he learns that his wounding is God's punishment for pursuing a love interest and thereby disobeying His requirement of chastity as the Grail King. Anfortas is condemned to suffer in a dual state of life and death for his arrogance (153-54). Anfortas' knights force him to repeatedly view the Grail to sustain his life. He pleads with his knights to stop showing him the Grail but the knights, following the Grail's prophecy of Parzival's return, persist in keeping Anfortas alive (251-52).

Anfortas' suffering is unsparingly graphic in detail: his condition is so terrible that "he can neither lie nor walk . . . nor lie nor stand. He leans, not sitting, in a sigh-laden mood" (157). Any attempts to heal him fail (154-55). Anfortas' sensitivity is so great that frost provides such intense pain that the spear had to be placed inside Anfortas' wound to conduct the cold from his body (157). He takes "to blinking constantly, sometimes for four days at a time. Then he was carried to the Grail, whether he liked it or not, and the illness forced him to open his eyes" (251).

The close link between Anfortas' suffering and God's will is symbolic of the biblical Fall of Man. Anfortas sins by loving himself more than God. H. G. Wilson sees Anfortas as representing "mankind in its fallen state, having broken the law of God" (Wilson 554). God's will is so great that Anfortas' Grail knights disobey his commands to stop showing him the Grail (Wolfram von Eschenbach 251). Wolfram alludes to Anfortas' disobedience through Trevrizent's recounting of Eve's decision to eat the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, as having "delivered us to hardship by ignoring her Creator's command and destroying our joy" (148). God punishes Anfortas' sin through the poison that slowly destroys his body, leaving him in a state of living decay.

Anfortas' suffering serves as a reminder of the destructiveness of sin, which can only be healed through redemption. By cleansing himself of sin, Parzival actualizes man's potential for redemption: He is then able to ask the Grail Question, "What troubles you?" Wolfram describes Anfortas' healing as a rebirth: "He who for Saint Silvester's sake bade a bull walk away from death, and who bade Lazarus arise—He himself helped Anfortas to recover and regain full health" (254). Anfortas, reborn, restores his faith in God and declares that he will fight in service to the Grail (262). Through Anfortas' suffering, though, Wolfram adds horrific depth to the development of the Fisher King.

In England, during the fifteenth century, Thomas Malory uses several important Arthurian works and legends as sources for his story, including The Alliterative Morte Darthur, the Tristan and Isolde legend, and the Grail Quest. His focus, though, is on Arthur and his knights; so, many other characters, including the Fisher King, take on secondary positions. Thus, the Fisher King plays a minute and undeveloped role in the Morte Darthur.

Malory's Fisher King lacks the importance of his counterpart in Perceval: he is rarely named by his title, save for a passing acknowledgement by Sir Lancelot, who "had sene toforetyme in kynge Pe[scheo]rs house" (Malory XIII.18.537.7). The Fisher King also lacks the substance of the Vulgate's Rich Fishermen and of Wolfram's Anfortas. Along with the Fisher King, multiple Maimed Kings appear, although they hardly have any bearing on the story. Most importantly, though, Malory creates confusion as to whether Pellam or Pelles is his Fisher King.

In The Tale of King Arthur, King Pellam is identified as a Maimed King. Pellam is the brother to Garlon, a traitorous knight who becomes invisible after putting on his armor and then slays other unsuspecting knights. Sir Balin kills Garlon in retaliation for killing a knight under his protection. Angered, Pellam fights Balin and Pellam breaks Balin's sword. Weaponless, Balin runs from chamber to chamber, searching for a weapon. He discovers the Holy Lance and delivers the Dolorous Stroke to Pellam:

"So when Balyn saw the spere he gate hit in hys honde and turned to kynge Pellam and felde hym and smote hym so passyngly sore with that spere, that kynge Pellam [felle] down in a sowghe. And therewith the castell brake roofe and wallis and felle downe to the erthe. And Balyn felle downe and myght not styrre hande nor foote, and for the moste party of that castell was dede throrow the dolorouse stroke." (II.15.53.38-43) 13

"So when Balyn saw the spere he gate hit in hys honde and turned to kynge Pellam and felde hym and smote hym so passyngly sore with that spere, that kynge Pellam [felle] down in a sowghe. And therewith the castell brake roofe and wallis and felle downe to the erthe. And Balyn felle downe and myght not styrre hande nor foote, and for the moste party of that castell was dede throrow the dolorouse stroke." (II.15.53.38-43) 13

Malory may have originally intended Pellam to be the Fisher King of his Grail quest: Pellam survives but his wounds cannot heal until the coming of Galahad. Perhaps this alone hardly distinguishes Pellam from other Maimed Kings, but there is a curious hint of Malory's direction: the Holy Lance is housed within Pellam's castle (II.14-16.52-54). Pellam's role as host to the Lance suggests that he is the ruler of the Grail Castle; although Pelles is, in fact, its ruler, it appears that Malory had at one point considered making Pellam his Fisher King.

Malory later identifies King Pelles as the Fisher King, calling him the "kynge Pe[scheo]r" (XIII.18.537.7). Pelles is the ruler of Corbenic, the Grail Castle, and is the father of Elaine; he helps to trick Lancelot into coupling with Elaine so that she can conceive Galahad (XI.2.479.27-32). In The Tale of the Sankgreall, Pelles is described as a Maimed King who was punished for drawing the Sword with the Strange Girdles while aboard Solomon's ship; a spear pierces through both of Pelles' thighs, producing wounds that cannot heal (XVII.5.583.18-30). Galahad eventually comes to Corbenic and heals Pelles by anointing his wounds with blood from the Holy Lance. Pelles then becomes a hermit and joins a religious order of monks (XVII.21.604.15-21).

In The Tale of the Sankgreall, Malory does not mention Pellam, suggesting that Malory has replaced Pellam with Pelles: both Pellam (II.16.54.11) and Pelles (XI.2.479.10-11) share the same genealogy as descendants of Joseph of Arimathea. Both Pellam and Pelles are guardians of the Holy Lance; however, the most indicative piece of evidence of Malory's intentions is found when Galahad states that "Balyn gaff unto kynge Pelles [the Dolorous Stroke]" (XIII.5.520.12). This is clearly false, as Balin had struck not Pelles but Pellam. It should also be noted that Pelles' wounding was, at one point, described as having happened while aboard Solomon's ship; however, aside from these glaring inconsistencies, Malory's replacement of Pellam with Pelles provides the necessary link, although loose, between his Tale of the Sankgreall and his Tale of King Arthur.

As Eugène Vinaver states, at first glance, "Malory's Tale of the Sankgreall is the least obviously original of his works" (758). He draws exclusively from the Vulgate, admitting so in the title: The Tale of the Sankgreall Briefly Drawn out of French Which is a Tale Chronicled for One of the Truest and One of the Holiest That is in This World. Not only does the Vulgate provide the source for the Dolorous Stroke and for Galahad's Grail Quest to heal the Maimed King, but the source of various other Maimed Kings can be found in the Vulgate: Nascien is wounded for using the Sword with the Strange Girdles (XVII.4.582.15-40;583.1-17). Mordrain is blinded for trying to see the Grail and is kept alive until he sees Galahad (XVII.18.600.22-35). A mysterious Maimed King, a "good man syke . . . [who] had a crowne of golde upon his hede" (XVII.19.602.26-27), appears along with the Fisher King during the liturgy scene at Corbenic. Each of these Maimed Kings is familiar to those who know the Vulgate, but they are not and pale in importance to the characters of Pellam and Pelles. Malory's use of the Vulgate does not incorporate its emphasis on religious edification; rather, he uses it as a template for his knights' adventures.

Malory's Morte Darthur concentrates on the rise and fall of Arthur's kingdom and the idealistic chivalric code. To do so, Malory needed to remove his focus from the religious nature of the Grail story, which, as R.M. Lumiansky notes, is "primarily a theological treatise on salvation" (Lumiansky 186). Malory's work is not a salvation piece but a tragedy; therefore Malory had to treat the Grail story like any of his other knightly adventures. He weaves the tragic theme of his work through the Grail quest, particularly when Arthur predicts that the Grail adventures will spell disaster for the fellowship of the Round Table (XIII.5-6.520). Thus the Fisher King has no other importance to Malory than to help drive the action of his larger plot.

Between Malory and T. S. Eliot, hardly any works were written which pertain to the Fisher King. For the most part, this void may be attributed to a lull in the production of Arthurian romance; however, the romantic nineteenth century works of Alfred Lord Tennyson and the Pre-Raphaelites brought about a rebirth of the Arthurian legend.

In the Idylls of the King, Tennyson distances himself from the Grail myth and, thus, the character of the Fisher King. There is only one instance where Tennyson has an opportunity to incorporate the Fisher King in his Idylls: Balin, Pellam, and the Dolorous Stroke; however, Tennyson avoids having Balin deliver the Dolorous Stroke to Pellam. Instead, Balin escapes Pellam's castle with the Lance, which Pellam condemns Balin for having defiled "heavenly things with earthly uses" (Tennyson lines 415-16). Pellam is most likely Tennyson's Fisher King, yet Tennyson ignores the Fisher King altogether in the Grail quest of "The Holy Grail."

Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival remained popular in German literature, and in the late nineteenth century, Richard Wagner worked the story into his opera, Parsifal. The premise of the story, Parsifal's healing of the wounded Amfortas, remains true to Wolfram, but Wagner places an emphasis on ritual and ceremony, such as the presence of scores of Grail knights, clergy, and maidens in the Grail Procession.

William Wordsworth provides a curious allusion to the Fisher King in his poem, "Poems on the Naming of Places": as several aristocratic figures, while crossing a wasteland, come across a "tall and upright figure of a Man / Attired in peasant's garb, who stood alone . . . worn down / By sickness, gaunt and lean, with sunken cheeks / And wasted limbs, so long and lean (Wordsworth 110). Wordsworth seems to be alluding to the Fisher King with the image of the sickly man standing amongst a wasteland, but he does not provide any other clues. It is interesting to note, though, how Wordsworth uses deceptive imagery, as the man alluded to as the Fisher King is actually a peasant; this foreshadows T. S. Eliot's ironical use of the Fisher King not as a king but in other forms.

Another British author, Ernest Rhys, treats the Fisher King in his poem "The Dolorous Stroke" and in his short dramatic piece The Masque of the Grail. "The Dolorous Stroke" recounts the episode in the Vulgate of the Dolorous Stroke given to King Lambor by King Hurlame. The focus of his short poem is how the Dolorous Stroke turns Logris into "the waste land of the earth" (Rhys "The Dolorous Stroke" 12).

In The Masque of the Grail, Rhys combines the Perceval, Peredur, and Vulgate stories to create a narrative that concentrates on the Grail Quest. In his notes, Rhys states that he treats The Masque of the Grail "as to make the Quest the real cause of the breaking up of the charmed circle of Arthur's Knights at Camelot" (Rhys The Masque of the Grail 42): as a result of the disbandment of the knights from the Round Table in search of the Grail, Arthur suffers a premature death (Rhys The Masque of the Grail 37). Galahad is forced to make a choice between following other knights on a pilgrimage to Sarras or healing King Pelleas, the Fisher King. Galahad sacrifices the glory of Sarras, where the knights believe eternal youth and the Grail lie (Rhys The Masque of the Grail 34), because he hears "another fainter cry, that comes as it might be from under the earth. It comes from the chamber of the Sick Lord the sailors call Sir Fisherman" (Rhys The Masque of the Grail 36). By healing Pelleas, though, Galahad learns that he has, in fact, achieved the Grail: "[Galahad] has found his Sarras by an old man's bed" (Rhys The Masque of the Grail 39). It is unclear, though, what happens to Pelleas after he is healed.

An American poet, Madison Cawein explores the mystical connection between the Fisher King and his lands in his poem, "Waste Land." Cawein describes his feeble Fisher King as a "lichen" (Cawein line 27), "moss" (26), a "weed" (32), and as "dust" (33); thus, Cawein's Fisher King is one with his lands. Eliot further develops this motif in "The Waste Land." In fact, there are such close similarities between Eliot and Cawein's poems that Robert Ian Scott suggests that they "can hardly be coincidental," particularly because Eliot would have probably read the January 1913 issue of Poetry, in which Cawein's poem appears, because Ezra Pound had a piece published in it (qtd. in Cawein).

T. S. Eliot's poem, The Waste Land, is one of the most important modernist poems. Eliot's poem critiques the direction in which society was heading and calls for a reassessment of values by looking to the past; thus, The Waste Land is filled with numerous allusions to both canonical and obscure texts, and forces the serious reader to search beyond the poem for its full meaning. The Waste Land, though, is a difficult poem to understand, and this difficulty is due in part to the Cubist structure of the poem, in which Eliot creates a single voice through the juxtaposition of disjunctive characters. 14 Daniel Tomlinson points out that, with this Cubist structure, "Eliot's poem simply circles round its subject, seeing it from many angles which are then intercut without transitions, the fragments being welded into a new conceptual unity in a complicated system of echoes, contrasts, parallels, allusions" (Tomlinson 64-65). Because of this Cubist approach, Eliot's allusions to the Fisher King create something that is less a character than a motif: there are many allusions to the Fisher King that do not embody one character but a multitude of characters, all of them suffering in their own ways but without being aware either of the nature of their suffering or even of their need for healing.

Eliot's Fisher King is embodied not only in his characters, but also in the wasteland itself; this may be attributed to his interest in the anthropological studies of Sir James G. Frazer and of Jessie L. Weston, to whose works he was so deeply indebted that he stated in his notes that "anyone who is acquainted with these works will immediately recognize in the poem certain references to vegetation ceremonies" (Eliot The Waste Land and Other Poems 71).

Eliot's Fisher King is embodied not only in his characters, but also in the wasteland itself; this may be attributed to his interest in the anthropological studies of Sir James G. Frazer and of Jessie L. Weston, to whose works he was so deeply indebted that he stated in his notes that "anyone who is acquainted with these works will immediately recognize in the poem certain references to vegetation ceremonies" (Eliot The Waste Land and Other Poems 71).

Frazer's work, The Golden Bough, is a comparative study of mythology and religion. Included in The Golden Bough are several accounts of vegetation gods—Osiris, Tammuz, Attis, and Adonis—who had power over the fertility of their lands. Rituals were performed to honor these gods, so that the lands would continue to produce sustenance (Frazer 325-27). Eliot may have had these vegetation gods and their rituals in mind as he attributes the barren landscape of The Waste Land to man's detachment from spiritual understanding.

In reading The Golden Bough, Weston saw a connection between these vegetation rituals and the Grail legend. Weston argues in From Ritual to Romance that the antecedents of the Grail legend "might [actually be] the confused record of a ritual" (Weston 4). In her interpretation, the character of the Fisher King can be explained as a life symbol which dates back to ancient fertility cults: "we can affirm with certainty that the Fish is a Life symbol of immemorial antiquity, and that the title of Fisher has, from the earliest ages, been associated with Deities who were held to be specially connected with the origin and preservation of Life" (Weston 119). Although Weston's theory has been discredited over time, it is an important key to unlocking Eliot's use of the Fisher King in The Waste Land.

Allusions to the Fisher King occur throughout the poem. In "The Burial of the Dead," without mentioning the Fisher King, the images of wasteland typography—snow "branches [that] grow out of stony rubbish," dead trees, rocks, and dust (Eliot The Waste Land lines 6-30)—imply that the lands are somehow connected to the suffering of the wounded king.

Madame Sosostris pulls the "man with the three staves" (Eliot The Waste Land line 51) from her deck of tarot cards; in his notes, Eliot associates this card "quite arbitrarily with the Fisher King himself" (Eliot The Waste Land and Other Poems 71). A clue to the underlying presence of the Fisher King is found in lines 71-73 where the protagonist asks his friend if a corpse that he planted has, because of the spring, begun to sprout: this is an allusion to the myth of Adonis (Frazer 327), from which, Weston argues, the character of the Fisher King was developed (Weston 112-14). In "A Game of Chess," the theme of sexual dysfunction alludes to the sexual wounding of the Fisher King and suggests that the people themselves are closely connected to the suffering Fisher King; this is most evident when, as his lover complains about their dysfunctional sexual chemistry, the protagonist turns to the sterility of the land: "I think we are in rat's alley / Where the dead men lost their bones" (Eliot The Waste Land lines 115-16). In "The Fire Sermon," we see a character engaged in the act of fishing, "musing upon the king [his] brother's wreck / And on the king [his] father's death before him" (Eliot The Waste Land lines 191-92). This is an allusion to Shakespeare's The Tempest, where a weeping Ferdinand hears soothing music, allaying his worries (Shakespeare I.ii.390-98). In The Waste Land, though, only the ominous sounds of the rattling of bones by scurrying rats (Eliot The Waste Land lines 194-95) and the "sound of horns and motors" (Eliot The Waste Land line 197) are heard, implying the encompassing presence of Eliot's wasteland. Eliot further muddles the identity of the Fisher King as he alludes to him through "fishmen [in a public bar who] lounge at noon" (Eliot The Waste Land 263). The presence of the Fisher King not only in the lands but also in its inhabitants supports Eliot's use of the Fisher King as a motif, as the suffering nature of the Fisher King exists everywhere. Moreover, Eliot is connecting the suffering of the Fisher King to the condition of modern human being: his choice of the word "lounging" to describe their activity has connotations of wastefulness, indicating a lack of meaning and purpose.

"What the Thunder Said" returns to the original wasteland typography of "The Burial of the Dead" and its images of rock, sterile land, and lack of water (Eliot The Waste Land lines 331-59). In this section, though, a kind of Grail Quest surfaces as a character moves through the barren landscape, perhaps in search of healing. The key to this healing comes not in a chalice, a Grail Question, or an act of compassion, but in pronouncements from godly thunder; however, there is no indication that these pronouncements have affected any change: the Fisher King character remains sitting "upon the shore / Fishing, with the arid plain behind [him]" (Eliot The Waste Land lines 423-24). With the lands still arid, Eliot makes it clear that its healing depends upon the individual, since the protagonist asks himself, "shall I at least set my lands in order?" (Eliot The Waste Land line 425). 15 This lack of recognition by the character creates ambiguity as to the possibility of regeneration, and so there is no immediate resolution to the suffering of the lands and its people, all embodied within the character of the Fisher King.

Taking T. S. Eliot's cue in The Waste Land, other twentieth century writers embody the character of the Fisher King in such modern forms as a manager of a baseball team, a buddy team of a bum and a disgraced former disc jockey, and a Vietnam War veteran. These embodiments are quite far from the kingly stature of the Fisher King in medieval Arthurian romance; however, the writers' decisions to incorporate essential characteristics of the Fisher King into their characters suggest that universal themes—in this case, a suffering person depending on another for his healing—remain fresh to contemporary audiences.

Bernard Malamud makes Pop Fisher, a coach of his failing baseball team, The New York Knights, the Fisher King of his novel, The Natural. (The film made from this novel will be discussed below.) At the beginning of the novel, Fisher has been suffering from a long and terrible losing streak. His baseball players have lost their motivation for trying to win their games, so they pass their time by playing pranks on Fisher and each other. Fisher, who has lost control of his team for quite some time, has taken to berating them with vain reminders that they "now hold the record of the most consecutive games lost in the whole league history, the most strikeouts, the most errors" (Malamud 56). Fisher even suffers from wounds that allude to the Fisher King: his hands have contracted athlete's foot, which is quite a remarkable condition (46).

If Pop Fisher and his Knights are the Fisher King and his knights of The Natural, then their playing field is their kingdom turned into a wasteland. Fisher acknowledges the deterioration of his field: "It's been a blasted dry season. No rains at all. The grass is worn scabby in the outfield and the infield is cracking" (45). As Fisher and his Knights overcome their losing streak later in the story, their playing field is restored to health: "Even the weather was better, more temperate after the insulting early heat, with just enough rain to keep the grass green and yet not pile up future double headers" (93).

Roy Hobbs is the Perceval figure of The Natural. Hobbs is a "natural" both in his ability to play baseball and in his simple and naïve manner (Lupack 213). Reflecting Perceval's natural ability to be a knight, Hobbs has a natural gift for baseball: although he had no prior league experience, Hobbs joins the Knights and leads them out of a slump toward the pennant, the Holy Grail of The Natural. Like Perceval's single-minded desire to be a knight, Hobbs is single-minded about being a baseball player. Hobbs fantasizes that people will recognize him as "the best there ever was in the game" (33). The second meaning of "natural" as simple-minded is appropriate to Hobbs because he repeatedly falls in love with femme fatales, fights with various figures such as Max Weber, a sports journalist who attempts to unearth Hobbs' past, and Pop Fisher, who constantly argues with Hobbs over the need for him to use his homemade bat for every swing. For reasons such as Hobbs' age, his frustration with baseball politics, his deteriorating health, and his obsession over wanting to build a life with Memo Paris, who is Pop Fisher's niece, Hobbs accepts money from the Judge to become involved in a plot to thwart the Knights' chances of winning the pennant by striking out during the championship game. However, Hobbs' pride in himself and his need to satisfy Pop Fisher causes him to have second thoughts about throwing the game. Hobbs has a change of heart during the game and helps his Knights approach victory, and although Hobbs does strike out at the end of the game, there is ambiguity as to whether or not his strikeout was intentional; nevertheless, Hobbs' strikeout causes the Knights to lose the pennant. Hobbs receives money from the Judge but does not accept it; rather, he savagely beats the Judge and leaves the money with him. After Hobbs rejects the money, though, Memo reveals that she has double-crossed him, and she shoots a gun at him, grazing Hobbs' shoulder. Hobbs sees his mistake in getting involved with Memo; but his fortunes continue to slip as Max Weber discovers Hobbs' hidden past and accuses him, in a headline, of selling out. This accusation prompts the baseball commissioner to issue a statement that if these allegations prove to be true, Hobbs will be banned from baseball and his records will be "forever destroyed." Whether or not Hobbs intentionally struck out at the end of the championship game, his weeping of "bitter tears" to end the story implies that he is doomed to disgrace (202-37).

The Natural is a study of the function of the hero in modern culture: Malamud places his hero in the context of baseball, a temporal and spatial form of entertainment that is so far removed from the business of everyday living as to breed hero worship. Iris Lemon, Hobbs' on and off-again lover and the mother of his child, comments on the importance of being a hero: "Without heroes, we're all plain people and don't know how far we can go" (154). With Hobbs' failure in his Grail Quest, though, Malamud troublingly suggests that the hero is an illusion in modern society. Hobbs fails in his quest and falls into disgrace at the end of the story, as he is doomed to become erased from baseball history (237). Pop Fisher retires without achieving his dream of winning the pennant, and so, the Fisher King of The Natural is not healed but continues to suffer.

Jonathan Baumbach elaborates further on this theory, in that he sees Malamud as having encompassed both romance and realism into The Natural: "a romantic, Malamud writes of heroes; a realist, he writes of their defeats" (Baumbach 102). By combining these two styles, Malamud is able to explore the function of the hero in modern culture. Baumbach argues that although people in modern culture "demand" the presence of heroes, they typically discover that their heroes are "fallible," and "pillory" these heroes for having "failed" (Baumbach 102). Roy Hobbs' natural ability to play baseball makes him a hero to baseball fans, but his moral impurity prevents him from embodying the hero in a perfect sense; thus, Hobbs' failure to win the pennant causes his fans to become disenchanted with him, and it sets into motion his downfall and public disgrace. Baumbach sees Pop Fisher and Sam Simpson as father figures to Hobbs (104). Both Simpson and Pop hope that, with Hobbs's success, they will discover redemption and renewal for their "own failed career[s]" (Baumbach 109). Baumbach suggests a parallel fate between Pop Fisher and Sam Simpson: just as Hobbs did not provide success but death to Simpson, Baumbach argues that Hobbs, through his failure to win the pennant, "for all intents and purposes, kills the old man [Pop Fisher]" (109).

Robert Ducharme agrees with Baumbach that Pop Fisher and Sam Simpson both serve as father figures to Hobbs, but he does not see Hobbs' failure to win the pennant as part of the inevitable failure of the hero in modern culture; rather, he argues that Hobbs' failure to win the pennant is due to a moral failure, Hobbs' failure to listen to the moral instruction of Pop Fisher: "though Pop wants desperately to win the pennant, he refuses to cooperate with Judge Goodwill Banner or Gus the Supreme Bookie in order to get it" (Ducharme 56). Hobbs' moral integrity is compromised by his "choice in women," of which leads towards Hobbs' "rejection of Pop's instruction and Hobbs' subsequent "betrayal" (56) of him.

Sidney Richman attributes Hobbs' failure to win the grail-like pennant to his failure to successfully complete the process of becoming a hero. This process is a "mythic formula" of "Initiation, Separation, and Return" (Richman 30). Richman argues that Hobbs does not complete the Return because he fails to "react to" and "understand" his "own past" (Richman 30), that is, his being shot by the crazed femme fatale. Hobbs does not constructively react to the event by making an immediate comeback to baseball; instead, he disappears for many years before making another attempt. He also does not understand why he was shot and so he repeats the cycle of choosing the wrong woman, this time Memo Paris. Hobbs' failure to complete the process of integration into the hero prevents him from achieving the spiritual fulfillment needed to win the grail-like pennant for Pop Fisher.

Earl R. Wasserman incorporates James Frazer and Jessie Weston's theories of the Grail myth being an interpretation of fertility and vegetation rituals into his analysis of The Natural. Wasserman sees Pop Fisher as embodying the fertility and vegetation gods of Weston's Fisher King, noting that Pop regrets not becoming a farmer and that Pop's heart "feels as dry as dirt" (Malamud 45). Hobbs, having "access to the sources of life" (Wasserman 48) through his ability to play baseball, restores vitality to Pop Fisher and his baseball field. Wasserman sees Hobbs as being in line with other fertility heroes of The Natural, Whammer and Bump, and does not see Hobbs' failure to win the pennant as having destroyed Pop Fisher and his lands: "in nature, quite independent of moral failure, life and strength are forever renewed" (Wasserman 50). Wasserman sees the aging Hobbs merely as being replaced by the "young pitcher" (Wasserman 50) who struck him out in the last game. This young pitcher, "whose yearning, like Pop Fisher's, is to be a farmer" (Wasserman 50), is next in line to replace Hobbs as a fertility hero.

Although there are various interpretations of Roy Hobbs' failure to win the pennant and its impact on Pop Fisher, each of these interpretations makes connections between the Grail story and modern culture. In other modern stories, various characters and situations, which embody the Fisher King and the Grail legend, make different connections between the legend and modern culture.

Two modern American novels, In Country and in Park's Quest, both associate the Fisher King with the Vietnam War, and with tensions within families. In both novels, young Perceval characters—Sam and Park—go on a Grail Quest to heal their respective Fisher Kings; however, both Sam and Park discover that this healing is much more complex than they originally thought, and that they too are in search of their own healings.

In Bobbie Ann Mason's In Country, the Fisher King is embodied in Emmett, a Vietnam War veteran. Emmett, who lives with his niece, Sam, is in a state of suspension between his time spent in Vietnam and his attempts to reincorporate himself into the contemporary world: he remarks that he and others "[are] embarrassed that they [are] still alive" (Mason 67). Emmett is unemployed, rejecting menial jobs so that he can find a job "worth doing" (108). The loss of the war and its subsequent negative public reception shatters Emmett's ideological self-identification, and now he is without purpose. Years after his service, Emmett still carries his army jacket around with him. He has become a bird watcher and searches for egrets, a bird commonly found in the jungles of Vietnam (63). Emmett habitually watches M*A*S*H, a television show that is a space for Emmett to project his war experiences. Emmett likes watching Frank Burns because he reminds him of his commanding officer, who was a "real idiot." Such comments while watching M*A*S*H are, according to Sam, "about all Emmett would say about Vietnam these days" (25). Emmett was not physically wounded in battle while in Vietnam, but Sam strongly considers that he suffers from the effects of Agent Orange (85). Along with various psychological conditions, Emmett has constant pains in his head that make him "jerk and twitch his forehead." Sam describes these pains as not so much strong as they are persistent, "like having a hangnail" (41).

Sam, the Perceval character, goes on a quest to heal her uncle and to learn about her own father. Throughout the story, she assesses her understanding of the war experience through M*A*S*H and through stories told by friends and family. Sam sees Emmett and other soldiers as victims of the war; their plight is that they are not "allowed to grow up . . . and become regular people" (140). Sam obsesses over healing these victimized veterans, so much that her mother worries that Sam is actually taking responsibility away from Emmett and the others for their own healing (167). Sam's ideological and one-dimensional understanding of the veterans becomes skewed after Sam reads her father's journal: Sam sees the war as a place not for the buddy experiences of M*A*S*H but as a place "with the rotting corpses, her father's shriveled feet, his dead buddy, those sickly-sweet banana leaves" (206). Her father's attitude to the war leads Sam to believe that he "loved" the war because it got "some notches on his machete" (222). Disgusted, Sam sees her father, Emmett, and anyone else involved in the war as savage killers; so she runs away to Cadwood's Pond, purportedly on a Grail Quest to find an egret, but actually to come to terms with the complexity of the war experience. She does so by imagining herself being in the jungles of Vietnam. Unsurprisingly, Sam fails in her quest to discover an egret; instead she gains a better understanding of her father, of Emmett, and of other soldiers who became engrossed in the war experience. Trapped within her imaginary war experience, Sam sees a figure, ostensibly a rapist, walking about in the distance. Sam cunningly devises a plan to hunt the figure down; however, the figure turns out to be Emmett, who had been searching for her. After a confrontation between the two, Emmett, while sobbing relentlessly, comes to terms with his psychological wounds by finally sharing with Sam his experiences in Vietnam (206-26).

If the Grail was not to be found in an egret, Sam realizes that Emmett's Grail is, in actuality, found in the Vietnam Memorial: "It was as though Emmett had found that bird he wanted to see" (234). The Vietnam Memorial is a step towards "closure" (241) for veterans. For example, at the memorial, somebody has placed a handwritten note by a dead soldier's name, apologizing to him for abandoning him during a firefight (242). The names on the wall are, in a sense, alive, as Mamaw struggles to touch Dwayne's name (243) and two soldiers search for a name, and when they find it, they "both look abruptly away" (242) in shame, as though they see the eyes of that soldier. The loss of the Vietnam War produced a generation of physically and psychologically wounded Fisher Kings, veterans who are left without purpose. The Vietnam Memorial functions as a Grail because it provides, as a giant tombstone, an outlet for the grief of the involvement in and the loss from the Vietnam War. This is not to say that Mason is implying that the Memorial will completely heal Emmett and the other Fisher Kings of the Vietnam War, but rather, that the Memorial serves as an important, perhaps necessary, step in the healing process after the War.